HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Fostering Healthy Childhoods: A Foundation for Resilient Generations

Introduction

All children have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health and access to health care services, as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ratified by the Government of Canada in 1991.[1] Health is essential for children’s present and future well-being, since childhood experiences can affect lifelong wellness. Further, as children are the upcoming generation, their health and well‑being reflect the future health of the country. Yet, when compared against other wealthy countries, Canada has been found to measure poorly with respect to children’s health outcomes. The systems in Canada that support children’s health suffer from long-standing issues. For example, children’s health care services have been under immense strain, burdened by backlogs and staffing shortages. Many children do not have adequate nutrition or levels of physical activity. Health inequities persist, with some children being afforded fewer opportunities than others to lead a healthy life. In recent years, those deficiencies in the state of children’s health in Canada have been exacerbated by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The pandemic disrupted the lives of children in Canada and may have extensive and lasting effects on their health and well-being.

Given that the objective of ensuring a healthy childhood for all requires that those pre‑existing issues and the impacts of the pandemic be addressed, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (the committee) adopted a motion on 9 February 2022 to take a holistic look at the status of children’s health. The motion stated, in part:

That Pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee undertake a study on children’s health and the recent impact the pandemic had on children and that:

- the study include, but not be limited, to addressing health care service backlogs affecting children, addressing inter-provincial barriers for research, data collection and sharing on children’s health, addressing children’s nutritional needs, addressing shortages of qualified health care workers capable of dealing with children’s health issues, in order to find potential solutions; [and that]

- the study include a focus on disparities in access to services for rural, Indigenous, racialized, and lower income communities.[2]

The committee held 11 meetings between 6 June 2022 and 21 March 2023 and heard from 46 witnesses. Witnesses included representatives from national and regional health profession organizations, advocacy groups and not-for-profit organizations, individual health care professionals and academics, and other stakeholders. The committee also received 62 written briefs. Additionally, the committee adopted a motion on 18 April 2023 stating “[t]hat the evidence heard by the committee in relation to its study of over-the-counter paediatric medication be taken into consideration by the committee in its study of children’s health.”[3] This report provides a broad view of the state of children’s health based on witness testimony. It summarizes the recent impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s health in Canada, as well as the long-standing issues with children’s health in Canada. It also gives an overview of the unique aspects of the health of children, as compared with that of adults, as well as federal initiatives related to child health. Finally, the report describes key concerns about children’s health in Canada, with potential solutions suggested by the witnesses. These suggestions are followed by recommendations to the federal government on ways to remediate the effects of the pandemic on children’s health, as well as foster resilience in children and the systems supporting their well-being, so as to enable a healthier childhood for all.

A Portrait of Children’s Health in Canada

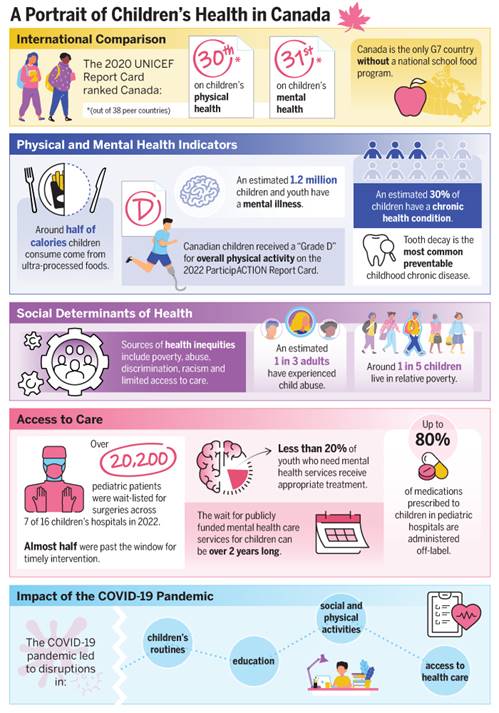

The witnesses and briefs painted a concerning picture of the overall state of children’s health in Canada. The infographic below (Figure 1) illustrates a selection of facts and figures presented to the committee regarding children’s mental and physical health, the social determinants of health, access to care, and the impact of the pandemic. Among the most striking statistics are the following:

- an estimated 1.2 million children and youth have a mental illness, and wait times for publicly funded mental health care services can be over two years long;

- over 20,200 children were wait‑listed for surgeries across 7 of 16 children’s hospitals in 2022;

- children received a “Grade D” for overall physical activity on the 2022 ParticipACTION Report Card;

- around half of children’s caloric intake comes from ultra‑processed foods; and

- social and economic factors such as poverty, abuse, discrimination, racism, and limited access to care have led to health inequities among children.

These issues are described in greater detail in the sections that follow.

Figure 1—A Portrait of Children’s Health in Canada

Source: Figure created by the Library of Parliament using information from testimony and briefs.

The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Health

“[T]he pandemic has had an outsized impact on the development, physical and mental health of children and youth. We owe them and we owe our country a singular focus on addressing those needs and putting them on the path to lifelong health.”

Alex Munter, President and Chief Executive Officer, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario

Witnesses across organizations and disciplines described how the COVID-19 pandemic had substantial, complex, and potentially long-lasting impacts on children’s health in Canada. The pandemic affected all aspects of children’s health, including their physical, mental, social, developmental, and spiritual well-being. Although COVID-19, as a disease, was found to be generally less severe in children compared to adults, other consequences of the pandemic were disproportionately felt by children. Thus, in the words of Bruce Squires, President of McMaster Children’s Hospital and Chair of the Board of Directors for Children’s Healthcare Canada: “Canada’s children and youth have borne the brunt.”[4]

Witnesses noted that the measures taken to limit the spread of the virus and protect the capacity of the health care system, such as school closures, restrictions on gatherings, and the postponement of elective surgeries, had unintended negative impacts on children’s health and well-being. The section below provides an overview of the pandemic’s various impacts on children’s health, as described in the testimony.

COVID-19 Complications and Other Infectious Diseases

Dr. Nathalie Grandvaux, professor at the Université de Montréal, stated that although children were found to be less affected by the symptoms of COVID-19 compared to adults, “[t]he risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections on children cannot be ignored.”[5] The committee heard how the Omicron variant, in comparison with previous strains, was associated with higher levels of transmission and hospitalization rates in children. Dr. Grandvaux highlighted that COVID-19 can sometimes lead to complications in children, including multisystem inflammatory syndrome.[6] Further, she noted that some studies suggest the possibility of both short- and long-term effects, such as neurological, cardiovascular and multisystemic impacts, following COVID-19 infection or reinfection in children. Therefore, Dr. Grandvaux cautioned:

The immunity established by vaccines and past infections does not confer complete and infinite protection against reinfections. Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection remains relatively short, leaving the children vulnerable to reinfections leading to lost learning days.[7]

Some witnesses spoke of how the pandemic led to indirect consequences related to infectious diseases in children, notably a rise in non-COVID respiratory diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Dr. Caroline Quach-Thanh, Pediatrician at the Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine, told the committee about recent resurgences of respiratory viruses in children and how these infections have, in turn, led to an increase in secondary bacterial infections.[8]

Additionally, in 2022, the rates of respiratory infections in children increased earlier and more markedly than had been expected. This situation created an unanticipated rise in demand for over‑the‑counter pediatric pain medication and contributed to extended nationwide shortages of these medicines.[9] These shortages created challenges for parents unable to find appropriate pain medicine to treat their sick children, increased pressure on primary care and emergency departments, and presented issues for hospitals who use these drugs to manage pain before and after children’s surgeries.[10]

Several witnesses noted a pandemic-related increase in vaccine hesitancy among parents,[11] which might lead to declines in rates of childhood immunization. Dr. Quach‑Thanh told the committee that this loss of confidence could reverse gains in health that vaccines have afforded for many years. In her words:

It would appear that concerns about the efficacy and safety of COVID-19 vaccines probably eroded the confidence of some parents in other vaccines that have been used for decades. This trust needs to be restored or we risk seeing a resurgence of these vaccine-preventable diseases and all the complications that come with them: meningitis, encephalitis, deafness, long-term side effects and deaths. Infectious diseases are also democratic: they will affect everyone, but will have more of an impact on those who are medically and socio-demographically most vulnerable.[12]

More generally, loss of trust in the health care system, as well as misinformation and disinformation during the era of COVID-19, were raised in the testimony as issues of concern for children’s health.[13]

Impacts of Reduced Access to Health Care Services and Health Human Resources

The committee heard testimony about how backlogs and wait lists for children’s health care services worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, to the point of “crisis.”[14] Witnesses from children’s hospitals reported “unprecedented volumes, occupancy and waits,”[15] a doubling of surgical wait lists, an increasing percentage of children waiting longer than the recommended wait time targets,[16] and emergency room waiting times as high as 24 to 32 hours.[17] According to Dr. James Drake, Chief of Surgery at the Hospital for Sick Children, delays in surgery were greater for children compared to middle-aged or older adults.[18] His testimony also emphasized how delays for children can be particularly damaging; interventions that do not occur within the appropriate developmental window can cause negative health outcomes:

All I can say now is that it seems to everybody that this is out of control. We have teenagers waiting for spine surgery who wait two to three years for their operation while their spinal curvatures increase. We have other patients who are limping around with a dislocated hip who can’t have their hip repaired because we can’t bring them into hospital.[19]

The committee heard about the existence of long wait lists in parts of the health care system beyond children’s hospitals. The pandemic was thought to have further limited an “already slow”[20] rate of diagnosis for children across Canada, including diagnoses for many cancers.[21] Multiple witnesses brought to the committee’s attention the issue of long wait lists for mental health care services.[22] Lack of access to timely mental health treatment “can literally be a life-or-death situation,”[23] Lindsey Thomson, Director of Public Affairs at the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, told the committee.

The volume of demand and long wait lists have also taken an emotional toll on pediatric health care professionals. Various pediatric health professions faced issues of staff retention and burnout caused by the increased demands and pressures of the pandemic. Witnesses described how the lack of sufficient staff to handle demand led to “moral distress” and elevated levels of burnout in the pediatric health care workforce:

Increasingly, my surgical colleagues and I are unable to look in the eyes of parents of children who need surgery and tell them with confidence that their child will be all right. This causes anxiety for families and moral distress for our surgical teams, who feel helpless in their ability to ensure optimized health outcomes for the children they treat.[24]

Coming into the emergency department and being told, “[t]here are 10 patients waiting for a bed. You have no beds tonight, so do whatever you can in the emergency department” is demoralizing, so people are leaving the practice. A lot of my colleagues are running a pediatric clinic in the community rather than taking shifts in the emergency department because it’s so brutal.[25]

Additionally, the closure of schools and daycares led to increased caseloads and burnout among speech‑language pathologists, according to Dawn Wilson. She stated:

A recent report indicated that there are insufficient speech-language pathologists working in Canadian schools to meet the needs of students who require their services. These staffing shortages are long-standing. However, closure of day cares and schools during COVID-19 further exacerbated the issue with increased levels of burnout and heavier caseloads. Prior to the pandemic, many indigenous children were already missing literacy benchmarks for their age groups.[26]

In short, “the pandemic exacerbated everything”[27] within health human resources, said Dr. Andrew Lynk, Chair of the Department of Pediatrics at Dalhousie University.

Mental Health Impacts

Many witnesses emphasized how the effects on children’s mental health were one of the most prominent negative impacts of the pandemic. Dr. Michael Ungar, Canada Research Chair in Child, Family and Community Resilience at Dalhousie University, characterized the pandemic as largely a mental, rather than physical, health crisis in children, saying:

Basically, the older you were, the less you were affected, at least from a mental health point of view. We very much downloaded the crisis. While the physical health crisis was on the elderly, the mental health crisis was largely visited upon our children, because their lives were the ones that were so disrupted.[28]

The committee heard about increasing levels of anxiety and depression[29] as well as hospital admissions for acute eating disorders and substance use disorders among children.[30] According to Dr. Mark Feldman, President of the Canadian Paediatric Society, the social isolation experienced during the pandemic may have contributed to these increases.[31] Dr. Marie‑Claude Roy, a pediatrician from the Association des pédiatres du Québec, further speculated that adolescent mental health declines may have stemmed from teenagers’ inability to develop and grow outside of family influences.[32] She explained that, during the pandemic, adolescents increasingly depended on screen time and social media, which can be a toxic source of images presenting an unrealistic perfection. Other witnesses noted that exposure to such content on social media has been linked to greater anxiety and depression[33] as well as eating disorders among female youth.[34]

By contrast, Dr. Tyler Black, clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia, indicated that the mental health impacts of the pandemic on youth were complex. He challenged “the dominant moral panic narrative that there have only been mental health deteriorations in youth”[35] during the pandemic, noting that some youth thrived during this period. Although the committee does not wish to diminish the tragic experiences of families who lost a child to suicide during the pandemic, it notes Dr. Black’s statement that suicide rates had decreased. In his words:

[D]uring the pandemic my advocacy has led me to correctly cautioning against the proclamations of increasing rates of suicide due to the pandemic. In fact, they have decreased. I have been in public responding to the horrific use of children’s mental health and suicide by politicians and non-mental health experts to justify resisting protections against a pandemic that has killed millions and has created over 10 million orphans worldwide.[36]

Losses in Healthy Lifestyles and Social Determinants of Health

The committee heard about profound losses in social determinants of health for children because of the pandemic, including with regard to education, social development, healthy behaviours, access to sports and recreation, and community supports. Concerns were raised over declining numbers of children who met physical activity targets;[37] increases in obesity, sedentary behaviours,[38] screen time and unhealthy food consumption;[39] delays in speech for some children who were born during the pandemic and who lacked adequate socialization;[40] and setbacks in learning following school closures and remote education.[41] Dr. Marie‑Claude Roy described the extent of these educational losses:

The pandemic set our young children’s reading and writing skills back 20 years. Good reading skills from the start of primary school are the most significant factor enabling children to do well in school and earn their diplomas. That’s an aspect that must be addressed. That’s why I discussed “educational” health in addition to physical and psychological health. We now have children in grade two or three who didn’t go to school during the pandemic. They’ve experienced interruptions since their education started.[42]

She also highlighted that school closures and lockdowns left some children more vulnerable to insecure home environments, as parents themselves experienced increased financial insecurity, domestic violence, and mental health issues.

Elio Antunes, CEO of ParticipACTION, emphasized the potential long-term health consequences of pandemic-related changes in healthy lifestyle behaviours in children:

The pandemic caused a sudden and drastic shift in the ways kids could access physical activity opportunities.

Playing with friends, in-person physical education classes, sports competitions and community programming all came to a halt. Kids were doing less and being more sedentary, and the pivot to virtual learning and calls to stay home transformed kids’ screens from an indulgence into a necessity for education and socializing. …

We should be extremely concerned not only about the impact COVID has had on kids’ physical activity today but about the long-term public health consequences if we don’t take action now.[43]

Widening Health Inequities

A number of witnesses highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic widened existing health inequities among children. The committee heard that it had a greater effect on girls; children in low-income households, rural and remote areas, and racialized and Indigenous communities; and children with complex health conditions.

Regarding school closures and educational disparities, Dr. Catherine Haeck, full professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal, referred to research on standardized tests scores showing that, generally, the students with the highest pre-pandemic scores continued to perform well during the pandemic, while those with the lowest fell further behind.[44] Similarly, Dr. Tracie Afifi, professor at the University of Manitoba, told the committee that children with more resources in their home environment may not have suffered or may even have improved in their well-being, while those with the least resources “would have suffered the most during the pandemic and perhaps have been left behind.”[45]

Dr. Marco Di Buono, President of Canadian Tire Jumpstart Charities, discussed how loss of access to community sports and recreation disproportionately affected girls and children living in low-income households.[46] Dr. Bukola Salami, professor in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Alberta, told the committee how the loss of access to sports and other pandemic factors disproportionately affected Black children and youth. Black youth, she said, faced a double pandemic: “the COVID-19 pandemic and the pandemic of the Black Lives Matter movement.”[47] She elaborated:

Black youth have experienced both oversurveillance and retraumatization from constantly watching news about the Black Lives Matter movement.

For many Black youth, also, sport is their outlet to de-stress and to overcome many societal inequities. The closure of recreational facilities and lack of access to sports had an impact on the mental health of Black youth.

Financial and food insecurity was a challenge for youth. Youth, especially those with disabilities, informed us of their experience of begging for food and going to churches just for the purpose of finding food available.

Some youth experienced separation from their families and challenges reuniting with them due to border closure and immigration restrictions.[48]

There were also inequities in access to public health measures. Many of these measures were not available to Indigenous children, in part due to limited infrastructure. Dr. Cindy Blackstock, Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, explained that “[o]nly 35% of First Nations homes have broadband access, so even remote learning or telemedicine isn’t an option in those kinds of circumstances.”[49]

Uncertainty and Lack of Data

The committee was told how uncertainty about the potential health impact of COVID-19 made it difficult to determine the effects of policy decisions on children. Witnesses said that the lack of data continues to represent a critical factor. For example, Dawn Wilson, Chief Executive Officer of Speech-Language and Audiology Canada, noted that although masks can hinder children’s ability to learn and understand speech, there is no research into the impacts of mask‑wearing on the long-term development of language skills.[50] A lack of baseline data for various children’s health outcomes prior to the pandemic was also cited as a barrier to understanding the impact of the pandemic on children.[51] Without this baseline data, it is difficult to determine how things have changed as compared with the period prior to the pandemic.

Although witnesses were generally unsure of the duration of the effects of the pandemic, some anticipated it would be long-term.[52] Dr. Haeck expected that the effects would be seen for at least another five years.[53] The committee heard that, whereas early action could lessen future impacts of the pandemic,[54] any measures taken should also be guided by data. As Traci Afifi said:

In terms of whether there will there be long-term impact, I would anticipate absolutely that there is going to be long-term impact, but again, what we need to understand and know how to respond to that is data.[55]

Long-Standing Challenges with Children’s Health in Canada

“Relative to our wealth, Canada punches far below its weight when it comes to children’s health.”

Emily Gruenwoldt, President and Chief Executive Officer, Children’s Healthcare Canada

A recurring theme in the testimony was the amplifying effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on existing children’s health issues. The lack of data, however, impedes a full understanding of the state of children’s health prior to the pandemic. Dr. Haeck noted, for example, that Statistics Canada’s National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth was last conducted in 2008–2009.[56]

The committee heard that pre‑pandemic issues relating to children’s health included delays for surgery and other health care services; rising rates of mental health issues and chronic diseases; staffing shortages; drug shortages; lack of data on children’s health outcomes; and health inequities among children. The length of wait times for pediatric surgery, for example, was said to be a problem that has spanned decades; in 2007, the Canadian pediatric surgical wait-times project flagged constrictions in capacity for children’s surgery.[57] Similarly, wait lists for children’s autism services in Ontario have grown over the past decade, rising from 1,600 in 2012 to 27,600 in 2020, according to Susan Bisaillon, Chief Executive Officer of Safehaven Project for Community Living.[58] There have also been “long-standing”[59] shortages of pediatric health care professionals, such as speech‑language pathologists.

Demand for children’s mental health and addictions care has also been increasing for many years.[60] Dr. Quynh Doan, a Clinician Scientist at the University of British Columbia, has observed consistent rises (6% to 8% per year) in pediatric emergency department visits for mental health issues since 2002.[61] Vaping rates among high-school students were said to have tripled in the years before the pandemic, rising from 9% in 2014–2015 to 29% in 2018–2019.[62]

The rising prevalence of chronic diseases, declining rates of physical activity, and unhealthy eating habits were also observed in children prior to the pandemic. According to the Chair of the Childhood Obesity Foundation, Dr. Tom Warshawski, the prevalence of childhood obesity doubled between 1978 and 2023, from around 6% to 12%.[63]

Dr. Marie-Claude Roy acknowledged that progress has been made across Canada over the years on some child health parameters, such as higher survival rates, improved vaccination rates and more effective prevention programs.[64] She noted, however, that many concerns remain. These concerns come into sharp relief when children’s health in Canada is measured against that of other wealthy countries. Witnesses and briefs gave the following examples:

- “You’ve heard about the 2020 UNICEF report card. Canada ranks 30th and 31st for children’s physical and mental health, respectively, out of 38 OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries. We’re in the bottom third of the report for such key indicators as child mortality, obesity, teen suicide and immunizations. In a country as rich and as developed as Canada, it’s inconceivable to most of us that we’re performing so poorly.”[65]

- Canada ranked 26 out of 38 OECD countries on child poverty rates on the 2020 UNICEF report card.[66]

- “Canada lags behind in protecting children’s environmental health[.] … According to UNICEF, Canada ranks 28th among 39 rich countries for overall environmental well-being of children and youth.”[67]

- Canada has “one of the highest rates of adolescent suicide in the developed world.”[68]

- “Compared to other similar countries, Canada lags behind in the availability of drug formulations specifically for the pediatric population.”[69]

- “Canada is the only G7 member and one of the only industrialized countries without a national school food program.”[70]

- “[W]e’re falling behind on an international scale. … Our organization works with 58 other countries in monitoring physical activity for children and youth, and we’re ranked 28 out of the 58 countries.”[71]

- “It’s a problem that we have in Canada that we haven’t repealed section 43 of the Criminal Code.” Corporal punishment of children has been banned in over 60 other countries in the world. “We’re behind on this.”[72]

- “Canada is the only OECD country that does not annually collect data on the health and wellbeing of its children.”[73]

- “Canada is one of the only countries in the western world that doesn’t actually have a national health human resources strategy.”[74]

- “Canada is the only rich country with universal health care that is without universal drug insurance.”[75]

- “Canada is the only G7 country where whole gross domestic expenditures on research and development have been in decline since 2001. It is now second from the bottom among G7 countries in this regard, with only Italy spending less.”[76]

Multiple witnesses mentioned that underfunding, which was sometimes described as “chronic,” has been an ongoing problem in children’s health in Canada. Underfunding was mentioned in relation to pediatric health human resources,[77] research funding on children’s health,[78] provincial and territorial dental care programs,[79] health care services for Indigenous children,[80] mental health care and addictions services for children,[81] programs promoting physical activity,[82] education,[83] and health prevention in general.[84] Dr. Catherine Haeck warned that underinvestment in children’s health could have negative consequences for generations far into the future:

It has to be said, however, that children are our future. If we don’t spend money on them, we are heading for a wall. We are eventually going to have to wake up. We can’t keep investing money elsewhere than in our children, because that is going to catch up with us later on and we are going to find ourselves with a very messed up population when they reach adulthood.[85]

Dr. Cindy Blackstock added that underfunding of health care services for First Nations children dates all the way back to Confederation, compounding inequities over generations:

Where does that inequality come from? It comes from the Indian Act, under which the federal government funds public services on reserve—everything from water to health to education to child care—and the provinces fund those for everyone else. Since Confederation, they have underfunded those services, creating a cascade of poor health outcomes for first nations children.[86]

Some witnesses were concerned that the attention paid to adults’ health care needs eclipses that of children. For example, Dr. Nathalie Grandvaux stated that “the health of children has been overlooked overall”[87] with regard to health research, while Dr. Erik Skarsgard, a member of the Pediatric Surgical Chiefs of Canada, cautioned that children waiting for surgery in adult hospitals “risk being overlooked in favour of adult surgical priorities like joint replacements and cataract surgery.”[88] The committee heard repeatedly from witnesses that children’s health needs should be made a priority in Canada.[89] As Bruce Squires put it: “I am here because our teams and the families they serve believe we need to sound the alarm on the health and well-being of Canada’s children and youth, and we need to make their health a top priority going forward.”[90]

Unique Considerations in Children’s Health

“More than ever before our children need advocacy within a public health system for their unique care needs, including prioritization for surgery. Children are not small adults and are not less deserving.”

Dr. Erik Skarsgard, Member, Pediatric Surgical Chiefs of Canada

The recognition that children have unique health needs was among the reasons witnesses gave for prioritizing this population. Children were said to have distinctive considerations in terms of the training of health professionals, the types of diseases that affect them and the way they experience these illnesses, their medication and medical device needs, and their developmental health. For example, children often require specialized health care professionals, who are often in short supply. The specific expertise of the pediatric health care workforce was highlighted by Emily Gruenwoldt, President and Chief Executive Officer of Children’s Healthcare Canada, who stated that “[t]he health care providers who care for Canada’s smallest patients are among the most highly specialized,” emphasizing that “[c]hildren are not tiny adults.”[91] The committee learned that, unlike in adult medicine, most children’s subspecialty care is located in university pediatric hospitals.[92]

The committee also heard that, although children may have specific health‑technology needs, medicines, medical devices, and vaccines are often developed for adults and may not have been adequately tested or approved in Canada for children. Even where they may have been approved, health technology assessments may not adequately account for children’s needs.[93] Sarah Douglas, Senior Manager at Pharmascience, explained ways that pediatric drug formulations differ from those of adults.[94] These differences can include specific ingredients and concentrations, form (e.g., liquid versus solid), or packaging. However, such formulations may be unavailable or have more limited availability in Canada. As a result, a high percentage of drugs prescribed to children in Canada are “off-label,” that is, used in a way that is not listed on the Health Canada‑approved product monograph. Dr. Erik Skarsgard highlighted similar issues for surgical devices, saying that many are used off-label because devices specific to children have not been approved in Canada.[95] Dr. Alain Lamarre, full professor at the Institut national de la recherche scientifique, added that the same concerns apply to vaccine development.[96]

The types of health problems experienced by children differ from those of adults as well. According to Dr. Tom McLaughlin, the field of pediatrics has “largely become a specialty of rare diseases.”[97] Given advances in medical care, more children with complex or rare diseases are living into adulthood. However, witness testimony pointed to difficulties with the transition from pediatric to adult care systems.[98] Further, the committee heard that type 1 diabetes, an incurable and life-long disease, poses a particular burden on children because it is more commonly diagnosed in childhood.[99] Witnesses said that tooth decay was the most common preventable chronic childhood disease in Canada,[100] and that cancer was the leading cause of disease-related death in children under the age of 15.[101] In addition to physical or mental health, Dr. Marie-Claude Roy also raised concerns regarding children’s developmental health. She stated: “Children are the only population whose development is constantly dynamic. Developmental challenges are extremely important and an integral part of children’s health.”[102]

Many witnesses highlighted the time‑sensitive nature of children’s health care. Because their bodies and minds are still developing, health interventions may need to be timed so as to avoid affecting developmental milestones.[103] If not addressed early, health, learning or communication issues can compound, amplifying problems. Ultimately, the committee heard that unaddressed health issues in childhood can have lifelong impacts. Alex Munter, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, spoke about how delays for care can affect children, their families, and even the broader society:

When a child has to wait for diagnosis for care or for therapy, they suffer. They suffer today and tomorrow, this year and next year. That’s bad enough, but on top of that, it could affect and it will affect for many the entire trajectory of their lives.

As you would well understand, when a child is sick, when a child has a disability and is not getting the therapy they need, it’s not just the child, but it is the whole family that is affected and often their parent’s ability to engage in the workforce, or in broader society.[104]

Conversely, intervening early to address children’s health was said to improve health and developmental outcomes. This theme was consistently raised by witnesses of various backgrounds and specialties, including dental care professionals, speech‑language pathologists, pediatricians, researchers, hospital administrators and mental health professionals.[105] Further, investment in child health was said to produce significant economic returns to society, as it would lead to healthier future generations of adults and reduce burdens on the health care system.[106] For example, Dawn Wilson told the committee that early intervention for children’s communication needs can have a multiplier effect:

Research has shown that the first three years are a critical period for normal speech, language and hearing development. Early identification of difficulties is therefore key to ensuring timely access to appropriate interventions for long-term success. Learning is cumulative. Difficulties not addressed early are compounded in later years.

…

A dollar invested in addressing problems today will mean many more saved in the long term. In other words, inaction now carries very high long-term costs. Delayed intervention costs 10 times more than if intervention were accessed early. Children who do not achieve optimal early language learning are not prepared or equipped for compulsory formal education by age five.[107]

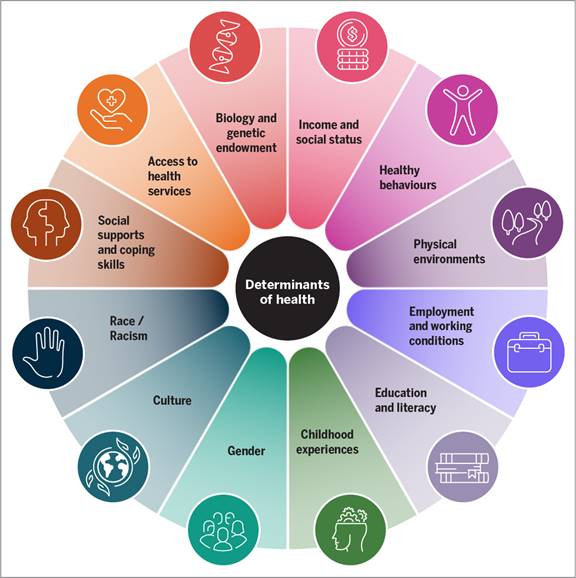

Another distinct consideration in children’s health is the types of factors that influence their health. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), childhood experiences themselves are one of the main determinants of health, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2—Determinants of Health

Source: Figure created by the Library of Parliament using Public Health Agency of Canada, Social determinants of health and health inequalities.

Psychologist Wendy Digout told the committee that the health of a child is linked to the family’s well‑being: “[W]hen we’re dealing with kids, we’re dealing with families.”[108] Many witnesses emphasized the importance of the social determinants of health, including household income, racism, education, housing, and historical trauma, as drivers of children’s health outcomes.[109] In the words of Patsy McKinney, Executive Director of Under One Sky Friendship Centre: “We know that children’s health isn’t based just on the medical system.”[110]

Children’s environments, at home, at school and in the community, can also influence their health and well-being. For example, the committee heard how families with low incomes may struggle to pay for food or children’s medication;[111] how childhood abuse can lead to mental and physical health issues later in life;[112] and how the health and well-being of First Nations children today has been affected by multi-generational trauma.[113] Supportive children’s environments can serve as protective factors for children’s mental health, enhancing resiliency. For instance, witnesses spoke of the protective benefit of adult role models, the role of schools in providing opportunities for physical activity, and the power of a sense of community belonging in protecting mental health. Dr. Lynk spoke on the importance of resiliency in children and how it can be supported in a variety of ways: “[R]esilience is more than just health care. It’s the family income. It’s how well you’re supported at school. It’s how well communities function. It’s about the environment.”[114]

Federal Initiatives Related to Children’s Health

Jurisdictional issues were raised during the testimony. Witnesses noted that many aspects related to children’s health, such as children’s hospitals, education, and the regulation of health professionals, fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction.[115] The federal government partially funds health care services offered by provincial and territorial governments via the Canada Health Transfer. However, aspects of children’s health fall under federal jurisdiction, and the federal government therefore has a role in multiple activities that can influence children’s health.[116] For example, Health Canada is a regulatory authority for children’s medicines and devices; PHAC is involved in various pandemic response efforts under its mandate for responding to public health threats; and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) funds research related to children’s health.

Additionally, Health Canada provides health care benefits to eligible refugees under the Interim Federal Health Program, and Indigenous Services Canada offers coverage to eligible First Nations and Inuit via the Non-Insured Health Benefits program. Witnesses also noted that federal departments outside the health portfolio may play a role in initiatives related to the determinants of health. For example, the Department of Canadian Heritage provides financial support for sports programming via Sport Canada,[117] the Canada Revenue Agency manages the Canada Child Benefit,[118] and Statistics Canada administers surveys related to child health and welfare.[119]

Although witnesses stressed the historic underfunding of children’s health, they also discussed a variety of federal initiatives directed at improving children’s health, as well as population-wide initiatives aimed at addressing COVID-19 impacts and improving access to health care services for all ages. Initiatives to address COVID‑19 impacts included the following measures:

- $2 billion in additional funding to the provinces and territories through the Canada Health Transfer to address backlogs for health care services;[120]

- $10 million in CIHR funding for 70 projects focusing on the impacts of the pandemic on children, youth, and families;[121]

- funding for a new cycle of the Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth to assess the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic;[122]

- $50 million to increase the capacity of distress centres during the COVID‑19 pandemic;[123]

- $240 million in 2020 to improve access to virtual health care services during COVID-19;[124] and

- Health Canada’s Wellness Together Canada, an online portal that provides 24‑7 access to mental health services.[125]

Several initiatives were targeted at improving access to mental health care, including the following measures:

- $5 billion over 10 years in additional funding to the provinces and territories through the Canada Health Transfer to improve access to mental health services—youth mental health services and integrated youth services are one of the priorities under the framework of the bilateral agreements;[126]

- $14.8 million over 36 months to Kids Help Phone;[127] and

- $45 million over two years to develop national mental health service standards[128]—February 2023, the Government of Canada announced that it would invest $5 million in national mental health and substance use standards for children, youth, and young adults.[129]

Among the initiatives that sought to address common childhood diseases and treatments were the following:

- “the 2007 federally funded Canadian pediatric surgical wait-times project, which resulted in nationally endorsed, diagnosis-specific wait‑time targets across the spectrum of children’s surgery;”[130]

- funding to address gaps in dental care—a commitment of $5.3 billion over five years, starting with children under 12 and beginning in 2022;[131]

- Health Canada’s ongoing work to develop a national strategy on drugs to treat rare diseases;[132]

- PHAC’s ongoing work towards a national autism strategy;[133] and

- Health Canada’s work on a Pediatric Drug Action Plan.[134]

Witnesses also referred to examples of the federal government’s various initiatives to promote healthy behaviours and communities:

- a $20-million annual fund to support community-based initiatives via the Healthy Canadians and Communities Fund;[135]

- the Community Sport for All Initiative, run by Sport Canada (under the Department of Canadian Heritage), which provides funding with the aim of increasing sport participation rates for underrepresented groups;[136]

- PHAC’s Community Action Program for Children and Canadian Prenatal Nutrition Program, two long-standing programs that promote child health, safety and wellness;[137]

- the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities Program, which has been running for over 25 years and which supports community-based early childhood development programs for Indigenous children and their families living off‑reserve;[138] and

- Health Canada’s Healthy Eating Strategy[139] and Canada’s Food Guide.[140]

Finally, witnesses cited federal investments in children’s health research, such as the following:

- CIHR’s dedicated Institute of Human Development, Child and Youth Health, and $195 million invested in children’s health research in 2021; and

- a commitment of $30 million in Budget 2021 for CIHR to fund targeted research into pediatric cancer—this funding was still active with no specific projects or results at the time of testimony but will involve the creation of a pediatric cancer consortium.[141]

Witnesses spoke positively about several of the above initiatives but also raised concerns that some initiatives were not specific to children,[142] have not yet been implemented or have not been fully implemented,[143] or do not sufficiently support certain groups of children.[144] Ultimately, the committee heard, outcomes are what matters most. As Emily Gruenwoldt stated,

we would expect our outcomes to be significantly higher, especially when we look at the investments we are making and the outcomes that are tracking towards those investments. It is an opportunity, I think, where not only would extra investments make a difference, but a broader strategy that incorporates both health and well-being metrics is overdue for this country if we’re going to measurably improve the health and well-being of children and youth.[145]

Fostering Healthy Childhoods

There was consensus among witnesses that more action was required on the part of the federal government to address the state of children’s health in the country. Witnesses spoke on the importance of recovering losses to children’s well-being brought on during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as addressing long-standing issues in children’ health. They also stressed the need to build resiliency in children and the systems that support them to ensure that children are protected in any future crisis. The proposed solutions are explored in detail below. They are grouped into five main categories: addressing barriers to pediatric health care services, promoting healthy lifestyles and preventing disease, shaping healthy environments for children, tailoring policy‑making to support children’s needs, and expanding data collection and research on children’s health.

Addressing Barriers to Health Care Services for Children and Youth

Witnesses emphasized the fact that, despite the importance of timely and appropriate pediatric health care, children living in Canada often face barriers to accessing health care services, especially in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. The barriers described include delays in accessing services due to backlogs or long waiting lists for care, shortages of pediatric health professionals, limited access to primary or community care, lack of availability of pediatric‑specific drugs, as well as financial and geographical barriers to care. The following paragraphs summarize suggestions from witnesses on how to reduce these barriers.

Targeted Federal Funding to Clear Backlogs in Pediatric Health Care Services

“I just want to highlight for this table how small our current investment is in children’s health as a percentage of the overall investment in health care across Canada.”

Bruce Squires, President, and Chair of the Board of Directors, Children’s Healthcare Canada, McMaster Children’s Hospital

Witnesses spoke of the urgent need to reduce waiting lists for children’s health care services, given the importance of providing childhood interventions as early as possible and within the appropriate developmental window to yield the best outcomes. Although some witnesses welcomed the $2 billion the federal government had committed to help clear the backlogs in surgeries caused by the pandemic,[146] Dr. Erik Skarsgard also raised concerns that children’s surgeries may be forgotten in federal funding transfers.[147] Pediatric surgical waiting lists were said to be equal to or greater than those for adults.[148] The committee was told that 20,200 children were wait‑listed for surgeries across 7 of 16 pediatric hospitals in 2022.[149] Witnesses suggested that, to ensure that children’s surgeries are prioritized, the federal government should allocate specifically to children’s services a portion of the health funding that goes to provinces and territories.[150]

Beyond simple waiting list numbers, Dr. Erik Sarsgaard emphasized the high percentage of children’s surgeries performed outside the recommended waiting time target, as much as 70% in some provinces.[151] Waiting too long for surgery can have particularly adverse effects for children. Dr. James Drake gave as examples common conditions such as strabismus, undescended testicles, orthopaedic deformity, and hearing impairment, which can lead to “lifelong issues of blindness, infertility, chronic pain and disability, and impaired speech development” if treatment is delayed too long.[152] Despite their time‑sensitive developments, children risk being left behind in funding because they represent a smaller portion of surgical procedures overall, as explained by Dr. Skarsgard:

We’re all so grateful for these transfer payments, but there’s always a risk that children are forgotten because children’s services represent such a small proportion. Less than 3% of surgeries done in my province are in children under 18. There’s been some talk about earmarking a certain proportion of those transfer payments to the provinces so that they must be used specifically for children’s services, and I applaud that. I encourage more of that thinking that targets resources specifically to children and does not rely on others to prioritize children with funding.[153]

The strategy of earmarking a portion of federal funds for children was also proposed as a solution to long waiting lists for pediatric mental health care services.[154] The committee heard about the “critical gap” in timely and equitable access to mental health care for children and youth, with many waiting six months to two and a half years for these essential services.[155] It was reported that every Canadian jurisdiction was dealing with long wait times for pediatric mental health care.[156] An estimated 100,000 children in Canada were on waiting lists for mental health services, according to Emily Gruenwoldt.[157]

Similar to delays in surgery, mental health issues that are not addressed, either at all or in a timely manner, can have serious repercussions, as described by Wendy Digout:

When we don’t have access to services for our children, they do end up in crisis. They end up self-harming. They end up with maybe more intensive eating disorders. Something that may have started as a bit of emotional eating can turn into a full eating disorder. They end up being suicidal, and they end up in our ERs. The ERs don’t know where to put them because there are so many wait-lists to try to get them in to see people.[158]

Considering the difficulties in accessing children’s mental health care, the benefit of early intervention for children with mental health problems, and the harms of untreated mental health programs, multiple witnesses recommended allocating 25%[159] or 30%[160] of the proposed Canada mental health transfer for children. Emily Gruenwoldt said that 25% would be a general reflection of the proportion of the Canadian population that is under 18 years old.[161]

In addition to suggesting funding earmarked for children, witnesses also discussed additional investments in an “underfunded” children’s health care system. For example, Dr. James Drake argued that funding models should reflect “the complexity of pediatric surgical, anaesthetic and hospital care,” which is higher compared to adults with the same condition.[162] Bruce Squires stated that the children’s health care system represents a relatively small amount of the total health care budget. He indicated that Ontario’s budget for children’s health care was estimated to account for some $250 million per year out of a total $75 billion budget.[163]

Several witnesses asserted that federal investments in children’s health should be tied to accountability measures.[164] Alex Munter noted that the impacts of previous federal investments in children’s health care were unclear, because they were not tracked.[165] According to Dr. Andrew Lynk, measuring outcomes would allow the provinces and territories to make comparisons and learn from one another.[166] Dr. Quynh Doan suggested an upfront commitment to collaboration between the federal government and researchers to measure the outcomes of funding:

From a perspective of someone who applies for a research grant, researchers are always asked if they are working with knowledge users and policy-makers to make their research applicable and useful. I would say for accountability for funding, the reverse should also be applied. When funding is distributed, there should also be a commitment to work with clinicians, scientists and researchers to put in place the measures and evaluation to measure the impact of that funding and investment.[167]

Dr. Marie-Claude Roy and Dr. Catherine Haeck cautioned, however, against an overly prescriptive approach to funding. They advised the committee that it would be important to allow flexibility in spending to account for the specific needs of each region.[168] As Dr. Haeck noted, “each province’s situation is different, in terms of both its cultural community and its health problems,” as well as its organization of services. In her view, provinces and territories have the “on the ground expertise” required for deciding how and where to invest funding to improve children’s health.[169]

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to devote an appropriate portion of new health transfer funds to pediatric surgical backlogs.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to increase mental health funding for children and devote an appropriate portion of the proposed mental health transfer to children.

Addressing Shortages of Pediatric Health Care Professionals

Shortages of health professionals across disciplines and specialties in children’s health was cited as one of the causes behind backlogs and wait lists for pediatric health care services.[170] Witnesses told the committee that the same crisis affecting the general health workforce in Canada extends to children as well.[171] For example, the committee heard that one children’s hospital had 250 staff vacancies,[172] that another was limited to using only 14 out of 16 operating rooms owing to nursing shortages,[173] and that there are not enough speech‑language pathologists in schools to meet students’ needs.[174] The workforce shortage was said to affect all children, not just those waiting for surgeries.[175] Many witnesses suggested national collaboration to address recruitment and retention issues in the pediatric workforce because of the specialized nature of the field. For further discussion and recommendations on health human resources, please see the committee’s report entitled Addressing Canada’s Health Workforce Crisis.[176]

A recurring theme in the testimony touched on the specialized training of various health professionals dealing with children, including pediatricians, surgical specialists, nurses, and allied health professionals such as occupational therapists and speech‑language pathologists. The small pool of practitioners with the necessary skills was said to be a challenge for recruitment, which often required Canada-wide or international searches. For instance, Dr. James Drake highlighted the limited number of qualified candidates trained to perform pediatric surgeries, recommending better remuneration:

Particularly with pediatric surgeons, we recruit people from all over the world, because the number of specialists in, for example, pediatric cardiac surgery or pediatric orthopaedic surgery, is small. It’s a very small pool of people we can access, and we are competing on the global stage. We compete with organizations in the States and the U.K. You name it and that’s where we’re competing. We really do need to have competitive salaries.[177]

The committee was told that national or international recruitment of pediatric health care professionals is complicated by provincial licensure requirements and the lengthy process for credentialing foreign‑educated health professionals.[178] For example, the committee heard that internationally educated nurses face a laborious credential assessment process with long lag times before they are permitted to practice in Canada. Dr. Salami explained that many of the credential assessment processes for internationally trained nurses are carried out in the United States, which slows processing.[179] Several witnesses suggested speeding up the pathways to credentialling international health professionals.[180] Witnesses also stressed the importance of ensuring that international medical graduates meet the requisite standards of practice in Canada.[181] Dr. Anne Monique Nuyt, Chair and Chief, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Université de Montréal and Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine, stated that there is a need for collaboration at a national level on licensure, even though the training and licensure of health professionals falls under provincial and territorial jurisdiction. She explained that only a limited number of programs train pediatric subspecialists for the whole country and that subspecialists are often recruited from overseas. Dr. Nuyt also emphasized that “[w]ithout a national coordinated and collaborative workforce plan, it will be impossible to train enough specialists to deal with the needs of Canada’s children.”[182] Given the limited number of practitioners in some subspecialities, such as pediatric neurosurgeons, the retirement of even just a few subspecialists affects waiting lists, according to Alex Munter.[183]

Certain witnesses also stressed the importance of training, recruiting, and retaining nurses and allied health professionals. Dr. Erik Skarsgard noted that the shortage of nurses was particularly acute and a “limiting factor” in pediatric surgeries.[184] He said that nurses as well as pediatric allied health professionals, such as respiratory therapists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and child life specialists, have additional training and highly specific skills related to children’s care. According to Dr. Nuyt, these allied health professionals are “essential” not only to children’s care but also for sharing the workload and avoiding burnout among pediatric subspecialists.[185] The pandemic was said to have caused significant issues with retention and burnout in the pediatric health care workforce.

Witnesses and briefs identified the need for a national health human resources strategy that accounts for the specific needs of the pediatric workforce.[186] Such a strategy was said to be crucial, both for addressing labour gaps in the present and for planning a resilient children’s health care system in the future.[187] The need for national pediatric health workforce data to inform this planning was noted by Dr. Andrew Lynk:

How many pediatric neurologists do we need in the next five or 10 years? I can’t even answer that—and I was president of the Pediatric Chairs of Canada—because I don’t have that data readily at my fingertips to plan. How many should we be producing? Who might be retiring? Who’s thinking about that?

This is where I think the federal government, on the advice of the Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Nurses Association and others, can have a centre to collate all this information and help us plan, so we don’t get burnt on this again.[188]

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada work in collaboration with the provinces and territories to implement a national pediatric health human resources strategy, which would include increased access to team-based primary care.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada work in collaboration with the provinces and territories to support expedited pathways to licensure and practice for internationally trained health care professionals.

Models of Care that Facilitate Earlier Intervention

Some witnesses argued that models of care that increase access to primary and community-based care, as well as provide a better integration of services, could not only relieve pressure on children’s hospital systems, but also facilitate earlier intervention and reduce health system costs. Several witnesses discussed integrated models of mental health services delivery, where care is provided by a multidisciplinary team.[189] Such a team could involve physicians, therapists, psychiatrists, occupational therapists, nutritionists, pharmacists, speech‑language pathologists or other specialists, all of whom would collaborate to support families.[190] Witnesses also discussed the use of primary care teams to expand access to primary care and reduce use of hospitals.[191]

Noting that, according to her research, many of the mental health difficulties experienced by youth in the pandemic were mild, Dr. Quynh Doan stated that accessible “mental health supports in the community are essential to curb escalation needs for more intensive, scarce and costly resources.”[192] She also pointed to a need for services to support youth who are gender questioning or non-binary. Dr. Tyler Black recommended expanding community-based care options for children and youth who are experiencing escalating mental health crises but do not require hospitalization, such as day treatment models, outpatient facilities, and home-based care. Such services, he said, were hugely lacking.[193] Similarly, Susan Bisaillon told the committee that additional investments in community-based care models can reduce the need for emergency department services by families caring for children with disabilities. In her opinion, these models could “liberate capacity in our struggling hospitals, provide choice and enhance the system of care.”[194]

The committee also heard calls for making mental health services more accessible in settings outside the traditional health care system.[195] Suggestions included integrating mental health supports within schools through guidance counsellors or teachers and building the capacity of churches or community leaders to act as initial responders to mental health challenges.

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada, in consultation and collaboration with municipalities, provinces, territories, and Indigenous peoples, work to ensure that all schools (preschool, primary, secondary, and post-secondary) have the necessary resources in order to ensure both the early detection of mental health and substance use issues in children, and the capability to work with students, parents, and health care professionals to ensure that these mental health and substance use issues are addressed as effectively as possible.

Enhancing Transitions from Pediatric to Adult Health Care Services

Children diagnosed with medical complexity or rare diseases are more often living into adulthood owing to advances in medical care. However, some witnesses highlighted the challenges these youth and their families face in the transition from pediatric to adult care systems.[196] Susan Bisaillon stated that “[m]any of these kids were never expected to become adults,”[197] noting that sufficient systems have not been implemented to support these youth once they reach adulthood, despite their need for care throughout their lives. As she put it: “Parents describe going from childhood into adulthood as being like falling off a cliff. Instead of celebrating their 18th birthday, this is a dreaded milestone.”[198] Similarly, Dr. Marie-Claude Roy’s testimony highlighted the lack of resources available for chronically ill patients—those who would not have survived to adulthood without advances in medical intervention—when they do reach adulthood: “We deal with them up to 18, 19, 20 or 21 years of age and have trouble letting them go because there are no resources for them.”[199]

To address this issue, Susan Bisaillon argued that a comprehensive, well-developed strategy is needed to support children with medical complexity and rare diseases as they transition from pediatric to adult systems of care. Such a strategy, she elaborated, would require a commitment and partnership with governments at all levels, particularly to address care needs, as well as appropriate funding models to ensure that this population has a stable income and affordable housing.[200]

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces, territories, and other stakeholders to ensure the greatest continuity of care possible for patients as they transition from adolescence to adulthood, including with respect to mental health and substance use supports.

Improving Access to Pediatric Drugs

“[C]hildren face additional barriers to accessing drugs. This is because Canadian policies, largely federal policies, governing the development, approval and reimbursement of drugs, are largely designed for adults.”

Dr. Tom McLaughlin, pediatrician and clinical assistant professor, University of British Columbia

Federal policies and drug costs can impede access to medicines for children. As mentioned above, the regulatory and health technology assessment processes for medicines in Canada are, for the most part, designed for adults.[201] As a result, pediatric‑friendly drug formulations may be unavailable or have more limited availability despite the unique needs of children compared to those of adults. Lack of availability of pediatric formulations means that up to 80% of drugs given to children are used off‑label[202] and up to 75% are compounded (e.g., crushing or mixing an adult pill with something else for use in children).[203] Both of these approaches can result in safety issues, such as dosing errors, as illustrated by Dr. Tom McLaughlin, pediatrician and clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia:

It might seem trivial to be talking about mixing pills with applesauce on the kitchen table, but this causes real harm. An eight-year-old boy in Mississauga named Andrew died a few years ago from a compounding error, and many more have been harmed by dosing errors.[204]

To enhance access to safe and effective medicines for children, some witnesses, such as Dr. Anne Monique Nuyt, called for Health Canada to continue working on a pediatric drug action plan.[205]

Witnesses and briefs also encouraged revisions to regulations for pediatric medications to facilitate access to pediatric drug formulations in the country.[206] Unlike regulators in the United States and Europe, Health Canada does not require drug manufacturers to submit data on pediatric populations.[207] Without this requirement, there is reduced impetus for drug makers to include children in clinical trials and submit pediatric‑specific formulations for Canadian approval, particularly because children in Canada represent a very small market.[208]

According to Dr. McLaughlin, regulatory issues can also contribute to pediatric drug shortages. Pediatric drugs not widely available in Canada are imported via the special access program “as a routine matter.”[209] The committee heard that whereas commercial liquid formulations for some drugs have been approved and are used in other countries, they are not available in Canada because the drug maker never applied for approval. The Goodman Pediatric Formulations Centre’s priority list included 17 such medications in March 2022, including gabapentin for epilepsy and metronidazole for infections.[210] Among the recommendations put forth to address these gaps were the following two suggestions: Canada should align its framework with pediatric drug‑specific regulations used in other countries that encourage manufacturers to apply for pediatric approval for drugs that may be used for children and incentivize research on pediatric drugs;[211] and Canada should leverage the assessments of trusted foreign regulators.[212]

In reference to the national shortages for over-the-counter pediatric pain medications that occurred during the pandemic, witnesses indicated that the federal government can build resilience and security into the pediatric drug supply chain to alleviate drug shortages. Shortages of liquid pediatric pain medicines were observed in the spring of 2022 and continued into the fall and winter of that year. According to the testimony, these shortages stemmed from a near doubling of the historical level of demand for children’s formulations of over‑the‑counter pain medications, issues in Canada’s drug supply chain and a lack of regulatory flexibility.[213] The committee was told that some countries, such as the United States, did not experience similar shortages during the same timeframe.[214]

Officials from Health Canada informed the committee that despite increased domestic production at the time, demand in Canada for pediatric drugs still outpaced supply.[215] The department therefore implemented regulatory flexibilities to permit the exceptional importation of products from other countries.[216] According to Gerry Herrington, Senior Advisor for Food, Health & Consumer Products of Canada, close collaboration between Health Canada and manufacturers is critical to the successful implementation of regulatory flexibilities that allow for additional production and importation, while maintaining consumer safety.[217] The committee was told about the need for clear and timely communication between Health Canada and those affected by shortages, including parents, caregivers, and children’s hospitals, to reduce panic buying, allow for planning, and ensure safe administration of drugs to meet children’s specific needs.[218]

Beyond the necessity of meeting immediate demands, another topic of discussion was the importance of addressing the root causes, to avoid future shortages and reliance on imports. Several witnesses suggested creating national stockpiles of critical medicines.[219] Hugues Mousseau, Director General of the Association québécoise des distributeurs en pharmacie, said that this work should be done in collaboration with drug wholesalers.[220] Dr. Saad Ahmed, a physician with the Critical Drugs Coalition, reiterated the call for a critical medicines list, which could be established building upon work already completed by researchers in Canada and the United States.[221] According to Emily Gruenwoldt, such a list should be created specifically for children’s medicines, the merit of strategic reserves for these medicines should be evaluated, and a list should be established of alternatives to use when certain pediatric medications are in shortage.[222]

Beyond physical stockpiles, Dr. Saad Ahmed noted strategies for critical medicines stockpiling could include “redundant manufacturing capacity in domestic or friendly countries’ manufacturing plants, or strategic reserves of the active pharmaceutical ingredients that create these finished pharmaceutical products.”[223] Other recommendations included investing in domestic supply chains and avoiding unpredictable cuts in drug prices that affect wholesalers, for example, by means of policies implemented by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board and the pan‑Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance.[224]

Witnesses described how, even when pediatric drugs are approved and available, the costs of these drugs can be a significant barrier to access. Two issues of particular concern were the high costs of drugs for rare diseases and out‑of‑pocket costs for children’s medications. Some witnesses supported a national strategy for high-cost drugs for rare diseases, given that children make up 70% of population who have a rare disease[225] and the medication cost can be “exorbitant”[226]—as high as $100,000, $1 million or $2 million.[227] An official from Health Canada stated that the department has started working with provinces and territories and other partners towards a national strategy on drugs for rare diseases.[228] According to Dr. Tom McLaughlin, the strategy should be designed to support the drug development pipeline, regulations, and reimbursement for these drugs.[229]

More broadly, the committee heard how families are struggling to pay for children’s medications, with one in six reporting financial difficulty filling prescriptions.[230] As mentioned above, Canada was described as the only country with universal and publicly funded health care that does not provide universal coverage for prescription drugs.[231] Although provincial, territorial and federal drug plans support drug access for low‑income families, the committee heard that the coverage may not extend to some pediatric drugs and varies widely between plans.

As Dr. McLaughlin said, “[d]epending on what province you live in, you might have almost all of your children’s drug costs covered, or you might have to pay out of pocket, even if you are below the poverty line.”[232] In his view, the economic analyses that inform the choice of drugs covered by public formularies rely on data that is lacking or limited with respect to certain pediatric conditions and fail to adequately capture children’s unique health concerns; as a result, there are gaps in pediatric medicine coverage on public formularies.[233] To resolve these issues, witnesses called for a national pediatric drug formulary and a pharmacare program that addresses children’s unique barriers to accessing medications.[234]

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to implement child‑friendly pharmacare and policies to improve access to pediatric formulations, including the Pediatric Drug Action Plan and the National Strategy for Drugs for Rare Diseases.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to implement the National Strategy for Drugs for Rare Diseases as soon as possible.

Eliminating Inequities in Access to Children’s Health Care Services

The committee heard that barriers to accessing care affect some population groups more than others, including children living in low-income households, rural and remote locations, racialized communities, and Indigenous communities. Witnesses offered a variety of proposals to address these inequities.

Reducing Costs for Health Care Services

As with the out-of-pocket costs for prescriptions drugs described above, witnesses told the committee that costs for certain health care services are a barrier for low‑income families. The challenges such families have paying for dental care was underscored by Dr. Lynn Tomkins, President of the Canadian Dental Association (CDA).[235] Oral disease disproportionately affects children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, according to the CDA’s written brief.[236] Dr. Tomkins noted that low-income families can fall through gaps in provincial and territorial public dental programs, which vary in levels of funding and remuneration for participating dentists.[237] She described some programs as “chronically underfunded,” with some dentists effectively “paying out of pocket” to provide care.[238]

An official from Health Canada spoke of federal plans to address gaps in dental care and the government commitment of $5.3 billion over five years, starting in 2022 with children under 12.[239] The CDA welcomed the Government of Canada’s interim dental care benefit for children, as well as its plans for a national public dental care program. With respect to the development of the national program, Dr. Tomkins urged the government to engage in meaningful consultation “with stakeholders, dentists, dental associations, the provincial and territorial dental associations, the provincial governments and the patients;” set national standards; and avoid creating additional administrative burdens.[240]

Therefore, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada work with provinces and territories to ensure that all Canadian children have access to comprehensive dental care.

The lack of public funding for mental health services was also identified as a barrier for low-income families. The committee heard from Carrie Foster, President Elect of the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, that only a small percentage of counselling and psychotherapy and psychologist support services are available through public plans.[241] She stated that about 10% of her clients have coverage through government services, such as the federal Non-Insured Health Benefits program and provincial programs. Ms. Foster estimated that 15% to 20% of clients have coverage through insurance plans, many of which do not cover psychotherapy. Those without coverage and in need of financial help may be charged a lower rate. According to Ms. Foster, psychotherapy can typically cost from $80 to $180 an hour, while psychologist services can cost over $200 an hour.[242] Psychologist Wendy Digout also described the practice of lowering rates or offering pro bono services to those in need, emphasizing the financial stress that patients are under, as well as the challenges that providers face:

From a practice point of view, taking that financial stress off the client and the family is really important.

For us as practitioners, there’s nothing more heartbreaking than having to turn someone away because you don’t have space in your schedule, or you already have five people who you are seeing pro bono and you just physically or financially can’t continue to do that.[243]

To address financial barriers to care, many agreed that mental health treatment, such as those offered by counsellors, psychotherapist, and psychologists, should be covered by the universal health care system.[244] Dr. Stelios Georgiades, Director of the Offord Centre for Child Studies, added: “[T]he big question is why wouldn’t we include it?”[245] Further, Carrie Foster questioned “whether we can afford not to,” since additional investment would, in the long run, improve children’s health and well‑being, and lower overall health care expenditures.[246] Dr. Tracie Afifi explained it thus: