HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Between 1972 and 1996, the CEIC (previously known as the Canada Employment and Immigration Commission) was responsible for setting an annual UI (EI) premium rate that served to reduce and eventually eliminate a cumulative surplus or deficit in what was then called the UI Account. Under this rate-setting mechanism, the premium rate was set each year so as to cover what was called the “adjusted basic cost” of UI (EI). This amount was equal to the “average basic cost” of benefit plus (minus) any amount required to remove or reduce a deficit (surplus) in the UI Account. The average basic cost of benefit was equal to a three-year average of UI (EI) costs.21 This approach precluded the build-up of a cumulative balance like that which exists today, unless of course the government intervened and established a statutory rate different from that permitted under the Unemployment Insurance Act.

Although this rate-setting approach served to reduce or eliminate a cumulative surplus or deficit over time, it was susceptible to pro-cyclical rate-setting. In other words, from time to time the premium rate would increase concurrently with the unemployment rate, a point in the business cycle during which lower, not higher, labour costs were needed to stimulate growth in employment. It should be noted that the adverse impact of this rate-setting mechanism was exacerbated, in some years (e.g., 1990, 1991 and 1992) by the withdrawal of taxpayers’ contributions to the program. As of 1990, all CRF payments for UI (EI) benefits ceased and the program became totally financed through employee and employer premiums.

To address the adverse effects of pro-cyclical rate setting, the Employment Insurance Act established a rate-setting process that required the CEIC to set a rate that, to the extent possible, would ensure that enough revenue was available to cover program costs and maintain relatively stable premium rates over the course of the business cycle. Unfortunately, the Act does not define a business cycle or premium rate stability, or set an upper limit on the “reserve,” albeit notional, that would meet these premium rate-setting objectives. Perhaps the greatest shortcoming associated with this rate-setting process is that there is no means of creating a real pool of reserves in order to meet the Act’s rate-setting objectives. While premium rate stability can be achieved in the context of a notional reserve, this approach necessarily has a direct impact on the budgetary balance of the government. By incorporating a cumulative surplus or “look back” component in the rate-setting process, the CRF must be called into service when the “stable” premium rate is unable to generate enough revenue to cover program costs. There is no doubt that the rate-setting mechanism established under section 66 of the Employment Insurance Act exposed the government to fiscal uncertainty.

I want to remind you, the whole point of the government deciding to move to a new premium-setting mechanism was that since the account was consolidated under this approach that looked back at accumulated surpluses, this could have significant destabilizing impacts on the fiscal management of the government. (Louis Lévesque, Department of Finance)22

In the absence of a legislated limit on growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, EI’s Chief Actuary set about to estimate the magnitude of the notional reserve that would satisfy EI’s rate-setting objectives. According to the Chief Actuary’s Report on Employment Insurance Premium Rates for 1998, an estimated notional reserve of $10 to $15 billion attained just before a downturn would suffice. This estimate was reiterated in subsequent reports covering the period 1999 to 2001. This estimate has not been revised since then, as CEIC’s rate-setting responsibilities were suspended in 2002.

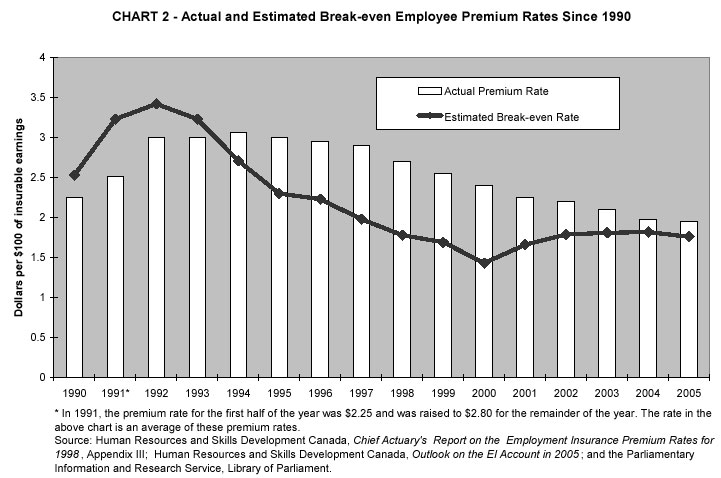

Although this notional reserve (i.e., cumulative balance in the EI Account) was reached around 1997-1998, EI premium rates continued to be set at levels well in excess of those required to cover program costs, as shown in Chart 2. Moreover, between 1998 and 2001, a period during which CEIC remained responsible for setting the premium rate, the government continued to set a premium rate that exceeded the upper end of the Chief Actuary’s estimated long-term stable rate and the recommended rate.23

With mounting pressure to address the continued growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, the government suspended section 66 of the Employment Insurance Act in 2001. In its place, section 66.1 allowed the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the ministers of Human Resources Development (now Human Resources and Skills Development) and Finance to set the EI premium rate for the years 2002 and 2003. The government indicated that during this period it would consult with Canadians and introduce a new premium rate-setting process by the end of 2003.

As this public consultation had not taken place by the time the February 2003 budget was tabled, the government reiterated its intention to consult the public on the creation of a new rate-setting process and extended its rate-setting authority to 2004. The budget also announced that interested parties could submit their views on a new rate-setting process until 30 June 2003. The new rate-setting process would be guided by five principles: (1) premium rates should be set transparently; (2) premium rates should be set on the basis of independent expert advice; (3) expected premium revenues should correspond to expected program costs; (4) premium rate-setting should mitigate the impact on the business cycle; and (5) premium rates should be relatively stable over time.24 Moreover, it was assumed that this new rate-setting process would be in place for 2005. However, in the event that the new process was not in place, the government extended by one year its rate-setting authority in the March 2004 budget. In doing so, it would set the premium rate in a manner consistent with the principles underlying the new rate-setting mechanism.

Since superseding CEIC’s rate-setting responsibilities, the government has continued to set an EI premium rate above that necessary to cover EI program costs (see Chart 2).25 While the Committee acknowledges that the government has reduced the EI premium rate every year since implementing the Employment Insurance Act, the speed at which these rates declined, especially after 1998, pales in comparison to the rate of growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account; the average break-even EI premium rate (including interest payments) for the period, 1998 to 2004 was around $1.70 per $100 of insurable earnings, some $0.61 per $100 of insurable earnings below the average actual rate for the same period.

The Committee recognizes that some of the gap between actual and estimated break-even premium rates is attributable to the fact that the latter includes interest payments. The government does not include interest payments in setting the premium rate, a somewhat odd approach in view of the fact that it pays interest, albeit notionally, on the cumulative balance in the EI Account. Of perhaps greater importance, the government has certainly levied real, not notional, interest charges in the past whenever the Account was running a deficit.

… from a fiscal management standpoint the interest credit is a notional transaction in the sense that it’s the accounting within the EI account, but it has no impact on the fiscal position of the government. What has an impact on the fiscal position of the government is the premium revenues coming in from employers and employees, the benefits in terms of going out, and the administration cost. It’s clear the intent in terms of the new premium-setting mechanism is to take those elements into account, because these are the elements that have a direct impact in any given year on the fiscal position of the government. (Louis Lévesque, Department of Finance)26

I. Looking Ahead: A New Approach to Setting EI Premium Rates

Most witnesses supported the idea of establishing a premium rate on the basis of expected program costs over a specific period of time, say between five and seven years. Others mentioned the business cycle as the rate-setting reference period. Irrespective of the reference period, all seemed to be in agreement that whatever period is selected, it must have a legislative basis.

There was also general support for a look-forward rate-setting process, and, in most cases, the proposed rate-setting model incorporated the concept of a rate stabilization reserve to offset the shortfall in revenues whenever the established rate failed to generate enough funding to cover program costs. Unfortunately, this rate-setting feature was not included in the five principles governing consultations on a new rate-setting process, although it should be noted that most participants addressed this issue anyway.

i. Establishing a Real Premium Rate Stabilization Reserve

As recommended earlier in our report, we believe that the government should enact the necessary legislation to create an Employment Insurance Fund Account. We also propose that the newly created Employment Insurance Commission establish and manage a premium rate stabilization reserve within this Fund, and that this reserve be estimated every five years to ensure that its size is sufficient to cover the cost of estimated program liabilities during the period over which premium rate stability is sought. Moreover, this stabilization reserve should be recalibrated following a major change to the EI program, especially when the change directly affects the program’s cyclical sensitivity.

Some witnesses suggested that a premium rate stabilization reserve should be set at $10 to $15 billion, the estimated, albeit dated, notional reserve that EI’s Chief Actuary deemed sufficient to meet program costs and maintain relatively stable premiums over the business cycle. Most Committee members believe that the Chief Actuary should re-estimate the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve that is necessary to satisfy the aforementioned rate-setting objectives over the rate-setting reference period.

Recommendation 4

The Committee recommends that a premium rate stabilization reserve be created and maintained within the proposed Employment Insurance Fund Account. This reserve should be estimated by the Chief Actuary of the proposed Employment Insurance Commission and re-estimated every five years. It should be managed prudently, provide the required liquidity needed to maintain premium rate stability over a five-year period, and should never exceed 10% of the most recent estimated premium rate stabilization reserve requirement.

Many witnesses either explicitly or implicitly indicated that EI’s Chief Actuary should play an important role in the new rate-setting process. This role would entail estimating the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve, as well as the premium rate that, given this reserve, would meet program costs and maintain stable premiums over the estimation period.

We’ve heard talk of eliminating the actuarial position. That would be outrageous. You need that. If you do not have that, some sort of arm’s-length person, you’ll run into a Workers Compensation Board scenario, where they don’t even do their cost claims studies, some of them, appropriately, and then you get all sorts of mischief happening. (Garth Whyte, Canadian Federation of Independent Business)27

General support also appears to exist for the principle that the premium rate be set on the basis of independent expert advice. We believe that the Chief Actuary should identify and use the necessary independent expert advice in fulfilling the proposed Employment Insurance Commission’s rate-setting mandate.

Committee members, and our witnesses, also support a transparent rate-setting process. In this context, the Chief Actuary would publish, not later than three months prior to the coming year for which the premium rate is to be set, a report outlining the details of the analysis underlying the recommended rate. We recognize that this rate must be approved by the Governor in Council, but Committee members are reluctant to afford the government a great deal of flexibility in revising the Chief Actuary’s and, by association, the proposed Commission’s recommended rate.

Many of those who appeared before the Subcommittee want future premium rates to increase or decrease in order to achieve objectives beyond those associated with the rate-setting process itself. For example, most of the witnesses representing employees recommended that the current premium rate be maintained or even increased so as to help finance, in conjunction with a reduction in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, numerous program enhancements. Groups representing employers, on the other hand, sought a continued reduction in EI premiums via a reduction in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, a rebalancing of employer/employee cost sharing, and higher premium refunds. It was also proposed that the new rate-setting process incorporate experience rating, a feature that would result in higher premium rates being charged to companies that generate above-average program liabilities compared to companies that tend to have relatively greater employment stability.

We think the premium rate should be increased. If we want to improve the employment insurance system, as we wish, the premium rate absolutely must be approximately $2.20 per $100. (René Roy, Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec)28

Given that employers and employees have already paid in over $47 billion in extra premiums to the government for the sole purpose of achieving rate stability, CFIB recommends that the government continue to lower the rates beyond 2004 and take the responsibility for future unexpected program shortfalls associated with the business cycle. (Garth Whyte, Canadian Federation of Independent Business)29

Most Committee members feel that the premium rate should be set annually so as to ensure that the proposed rate stabilization reserve is solvent, that program liabilities can be met and that premiums can remain relatively fixed over a look-forward period of five years. The costs associated with future program enhancements or other changes pertaining to program financing would necessarily be reflected in both the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve and the break-even premium rate covering the rate-setting reference period.

Recommendation 5

The Committee recommends that starting in 2005:

i) the Chief Actuary of the proposed Employment Insurance Commission utilize independent expert advice to estimate annually a break-even premium rate that would ensure program solvency and premium rate stability over a five-year, look-forward period;

ii) the Chief Actuary utilize independent expert advice to estimate quinquennially the size of premium rate stabilization reserve that would insure program solvency and premium rate stability over a five-year period; and

iii) the proposed Employment Insurance Commission publish its recommended break-even premium rate and underlying analysis by 30 September in the year prior to the year for which the recommended rate applies.

Recommendation 6

The Committee recommends that if the rate recommended by the proposed Employment Insurance Commission is, for some extraordinary reason, different from that which the Governor in Council wishes to approve, then the government must, in setting a different rate, amend the Employment Insurance Act by establishing a statutory premium rate for a period not exceeding one year. This proposed legislative change must be subject to a vote in the House of Commons.

| 21 | More specifically, the average basic cost of benefit was equal to the average total cost of UI (including administration costs) for the three-year period that ended concurrently with the second year preceding the year for which the average was computed. The premium rate that would cover the average basic cost of benefit was the statutory or minimum premium rate that could be established in a given year. |

| 22 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (12:10), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 23 | In 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001, the Chief Actuary’s recommended rate was $2.40, $2.30, $2.25 and $2.10 respectively per $100 of insurable earnings; while actual rates were $2.70, $2.55, $2.40 and $2.25 respectively. |

| 24 | Department of Finance, The Budget Plan 2003, 18 February 2003, p. 183. |

| 25 | According to the Chief Actuary’s Outlook for the EI Account in 2004, estimated break-even premium rates (including interest payments) for 2002, 2003 and 2004 were $1.79, $1.77 and $1.81 respectively per $100 of insurable earnings; actual rates, on the other hand, were $2.20, $2.10 and $1.98 respectively. |

| 26 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (11:40), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 27 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (16:35), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 28 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (19:30), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 29 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (15:45), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |