SECU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Fighting the Phenomenon of vehicle Thefts in Canada

Introduction

On the decline over the past two decades, Canadians have noticed a significant increase in vehicle thefts across the country. According to Statistics Canada, 83,416 vehicle thefts were recorded in 2021, compared to 105,673 in 2022.[1] This rise in the number of vehicle thefts provides only a glimpse of the number of people affected by this growing problem.

As outlined in this report, vehicle theft is a complex problem that requires a collaborative response from multiple stakeholders, including manufacturers, insurance companies, shippers, law enforcement, and governments, to find solutions to address this issue described by some as a “national crisis.”

Study Background and Committee Mandate

On 23 October 2023, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security (the committee) adopted a motion to undertake a study “on the growing problem of car thefts in Canada and on the measures the federal government has taken to combat this criminal activity.”

Between 26 February and 23 May 2024, the committee held six public meetings where 42 witnesses were heard. A total of 11 briefs were received as part of this study. On 13 May 2024, the committee also visited the facilities of the Port of Montreal and the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA).

National Summit on Combatting Auto Theft

On 8 February 2024, before the committee’s study began, federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal government officials, industry leaders and law enforcement representatives from across the country came together for the National Summit on Combatting Auto Theft (the Summit) to discuss potential solutions.

At the conclusion of the Summit, the federal government announced the introduction of immediate measures to combat this problem, including a $28 million investment in the CBSA to conduct more investigations and reviews on stolen vehicles, and to enhance collaboration on investigations and information sharing with Canadian and international partners. The federal government also announced that it was considering banning certain devices used to steal vehicles by copying the wireless signals for remote keyless entry, such as the Flipper Zero.

Participants at the Summit also signed a Statement of Intent on Combatting Auto Theft recognizing the need to coordinate and enhance various efforts to combat vehicle theft.[2] Furthermore, the signatories committed “to take leadership within [their] roles and responsibilities to support and enhance the ongoing efforts of Police, industry and/or Governments, in order to further deter auto theft and address related issues.”

Several witnesses noted that the Summit highlighted the need for collaboration between stakeholders.[3] The need for a collaborative approach between various stakeholders is also addressed in Chapter 4.

Port of Montreal Visit

On 13 May 2024, the committee visited the facilities of the Port of Montreal and the CBSA as part of its study on vehicle theft. The committee was briefed on the role and mandate of the Montreal Port Authority (MPA) and CBSA, as well as on the procedures for the import, export, and search of containers. The committee also had the opportunity to observe the collaboration between various police services and to witness the recovery of several stolen vehicles that were found during the container search by CBSA agents. The police officers present explained to the committee that the vehicles found are inspected to identify their provenance and whether other crimes have been committed with them. If a crime has been committed with a recovered vehicle, it is more thoroughly searched to find evidence. The police services and the CBSA also work closely together since only CBSA agents have the authority to open and search containers, while the police services carry out investigations to identify the individuals responsible for the thefts.

Report Structure

The report is divided into four chapters and contains a total of 44 recommendations scattered under each chapter of this report. Chapter 1 provides a contextual overview of Canada’s vehicle theft problem. Chapter 2 discusses the involvement of organized crime in relation to vehicle theft. Chapter 3 addresses the complexity of the port environment and includes suggestions to facilitate responses to vehicle theft in this environment. Lastly, Chapter 4 suggests other measures that can be taken to combat vehicle theft.

Chapter 1: Context of Vehicle Theft in Canada

The witnesses heard during the study noted that vehicle thefts have increased significantly in Canada, particularly in Ontario and Quebec. Testimonies also revealed that a significant number of stolen vehicles transit through the Port of Montreal before being shipped overseas. Other witnesses expressed concern about the heavy financial burden that vehicle thefts have on Canada’s economy. Vehicle theft affects all Canadians, notably by depriving them of their means of transportation, leading to an increase in their insurance premiums and reducing their sense of security.

Statistics on the Increase in Vehicle Thefts in Canada

In terms of the rise in vehicle thefts in Canada, David Adams, President of Global Automakers of Canada,[4] said that one vehicle is stolen every five minutes across the country. Thomas Carrique, Commissioner (Commr) of the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, added that as of 29 February 2024, there have been over 3,000 vehicles stolen in Canada since 8 February 2024. Figure 1 shows the evolution of vehicle thefts in Canada between 2005 and 2023.

Figure 1—Total Vehicle Thefts in Canada between 2005 and 2023

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table 35-10-0177-01 Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, Canada, provinces, territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Canadian Forces Military Police.

a.: In the early 2000s, vehicle theft became a major scourge for Canadians. In 2005, the Government of Canada took steps to address this, including modernizing the Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standard to require vehicles manufactured after 2007 to be equipped with an immobilization system and vehicle identification number (VIN) plates to be installed on the frame of the vehicle. See Government of Canada, Background: Vehicle immobilizers.

b.: In 2007, changes to the Canadian Motor Vehicle Safety Standard and VIN requirements came into effect. These legislative changes have made it possible to reduce vehicle thefts, as shown in Figure 1.

Note: Équité Association published a First Half of 2024: Auto Theft Trend Report on 16 July 2024. The report states that, for the period from January to June 2024, vehicle thefts decreased by 17% compared to the same period in 2023.

Terri O’Brien, President and Chief Executive Officer of Équité Association, reported that in less than three years, vehicle theft had risen by 53% in Ontario and by 66% in Quebec. In that regard, Figure 2 shows the number of vehicle thefts by province in 2023 while Figure 3 lists the 10 cities with the highest number of vehicle thefts in 2023.

Figure 2—Total Number of Vehicle Thefts by Canadian Provinces in 2023

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table 35-10-0177-01 Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, Canada, provinces, territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Canadian Forces Military Police.

Figure 3—Total Number of Vehicle Thefts by the Top Ten of the Census Metropolitan Area in 2023

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table 35-10-0177-01 Incident-based crime statistics, by detailed violations, Canada, provinces, territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Canadian Forces Military Police.

Ontario: Greater Toronto Area

Several witnesses told the committee that vehicle thefts have increased notably in the Greater Toronto Area. Huw Williams, National Spokesperson for the Canadian Automobile Dealers Association, reported that vehicle thefts have increased by 300% in the Greater Toronto Area since 2015.

Similarly, Deputy Chief Robert Johnson, Deputy Chief of Police of the Toronto Police Service, noted that Toronto has seen a dramatic spike in vehicle thefts, more than anywhere else in Canada. He said that there were more than 12,000 vehicles stolen in Toronto alone in 2023. To put this in perspective, he added that it represents about 34 vehicles stolen every day in 2023, or one every 40 minutes, which amounts to approximately $790 million.

Deputy Chief Nick Milinovich, Deputy Chief of Police of the Peel Regional Police, noted that in 2023 over 7,000 vehicles were stolen in the Peel region, which is almost one vehicle stolen per hour. He added that some days, 1.5 vehicles were stolen per hour.

Deputy Chief Johnson stated that since 2018, Toronto police have recovered 20,000 vehicles, or 46% of stolen vehicles. He added that, in recovering these vehicles, they arrested 1,300 offenders and laid over 5,000 related charges.

Quebec: Montreal

Pierre Brochet, President of the Association des directeurs de police du Québec, said that “[i]n 2023, over 15,000 vehicles were stolen in Quebec. That’s an increase of 57.9% over three years.”

Specifically, Commander Yannick Desmarais (Comd.), Section head of the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal (SPVM), stated that the number of vehicle thefts increased by 147% in Montreal from 2020 to 2023. He noted, however, that the SPVM’s most recent statistics show a 30% drop in thefts in Montreal in the first quarter of 2024. Comd. Desmarais explained that these statistics are a result of police operations, efforts with other partners, and public awareness.

British Columbia

Kelly Aimers, Chief Actuary of the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia (ICBC), mentioned that, according to the Integrated Municipal Provincial Auto Crime Team (IMPACT), in 2023, British Columbia (B.C.) had its lowest rate of vehicle thefts since 2018.

Ms. O’Brien said that B.C. is less affected by the vehicle theft problem than other Canadian provinces since the illegal markets overseas are across the Atlantic. She also explained that the province may be less attractive for criminal organizations since crossing over into U.S. territorial waters could prove to be an obstacle. She said that if

they go south, they're almost immediately out of the port of Vancouver or other B.C. ports and into U.S. territory. If they go north, they hit Alaskan waters and are, again, in U.S. territory. Therefore, they are subject to search and seizure by U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Shabnem Afzal, Director of Road Safety at ICBC, noted that most vehicles stolen in B.C. are not exported, which explains why 7 out of 10 vehicles are recovered. She also stated that most thefts in B.C. involve older vehicles rather than newer models.

Three Possible Trajectories for Stolen Vehicles

According to testimony heard during the study, stolen vehicles generally have three possible trajectories, namely being exported overseas, having their vehicle identification number (VIN) cloned or “revinned” and being resold within Canada, or being disassembled for parts.[5] Deputy Chief Milinovich reported that about 60% of vehicles were being stolen for export, while 40% were being revinned and resold within Canada.

Export Overseas

First, with regard to the export of vehicles overseas, Deputy Chief Johnson explained that

… like other crimes led by organized crime networks, they do not care about borders or jurisdiction. A violent carjacking in Toronto can end up with an arrest in Hamilton. We know that these stolen vehicles often wind up leaving Toronto and end up sold around the world by organized crime groups.

In Canada, the preferred route for exporting stolen vehicles seems to be the Port of Montreal. Mr. Williams explained that stolen vehicles were being sent by rail to the Port of Montreal. However, during the Port of Montreal visit, the committee was told that most of the stolen vehicles arrived by truck. Mr. Williams added that the vehicles were then exported, without CBSA inspection, to Africa, Eastern Europe, and other countries to be resold by international organized crime.

Julien Baudry, Director of Public Affairs at the MPA, explained why the Port of Montreal is a prime target for exporting vehicles. He said that

[t]here are essentially two reasons for this: We are very close to the major urban centres of Quebec and Ontario, but we are also the main container port for supplying markets in Africa or the Middle East. According to [INTERPOL], these two markets are among the destinations for these stolen vehicles.

Chief Inspector Michel Patenaude (Ch. Insp.) from the Sûreté du Québec (SQ), also highlighted the Port of Montreal’s importance for the export of stolen vehicles from Quebec and Ontario.

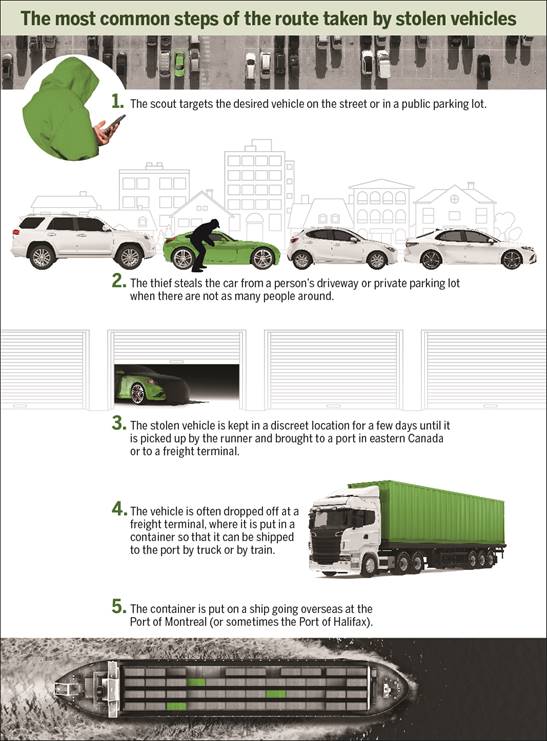

Figure 4 shows the most common steps of the route a stolen vehicle may take, from the time it is identified until it is exported.

Figure 4—The Most Common Steps of the Route Taken by Stolen Vehicles

Description: The infographic outlines the five most common steps of the route taken by stolen vehicles.

1. The scout targets the desired vehicle on the street or in a public parking lot.

2. The thief steels the car from a person’s driveway or private parking lot when there are not as many people around.

3. The stolen vehicle is kept in a discreet location for a few days until it is picked up by the runner and brought to a port in eastern Canada or to a freight terminal.

4. The vehicle is often dropped off at a freight termina, where it is put in a container so that it can be shipped to the port by truck or by train.

5. The container is put on a ship going overseas at the port of Montreal (or sometimes the Port of Halifax).

VIN Revinning and Resaling

Second, when it comes to revinning and resale in Canada, Ms. O’Brien explained that “[i]n revinning, a vehicle identification number—or VIN—is changed, in essence, to create a false identity for that vehicle. By creating a new identity for these vehicles, criminals can sell them to unsuspecting Canadians, use them to commit other crimes or export them for significant profit.”

Dan Service, Principal of VIN Verification Services Inc., reported that vehicles are “revinned, registered, given credibility by their provincial government registry and then resold to unsuspecting consumers within Canada.”

Resale of Parts

Third, Ms. O’Brien said that a small percentage of the stolen vehicles were not exported, but actually dismantled for parts. She specified that catalytic converters are prized by thieves because they have precious metals embedded in them. She added that mass thefts occurred at dealerships where catalytic converters have systematically been stolen.

Financial Burden

Comd. Desmarais noted that vehicle theft is a crime that has a significant impact on the victims, both financially and in terms of their sense of safety. Furthermore, according to Ms. O’Brien, the current vehicle theft problem has resulted in Canadians being exploited twice: once when they are victimized by vehicle theft and again when the proceeds from that crime are funnelled back into the community, funding guns, drugs, and other illegal activities.

Regarding the financial burden, Ian Jack, Vice-President of Public Affairs at the Canadian Automobile Association (CAA), stated that

… the costs of vehicle theft are rising astronomically. There have been $1.2 billion in additional payouts in 2022, and these costs are being passed on to consumers in the form of higher premiums and, in some cases, vehicle surcharges of up to $500 if you happen to be unlucky enough to own one of the top 10 most stolen vehicles. We believe that these costs will be significantly higher for 2023.

Figure 5 lists the 10 most stolen vehicles in Canada in 2022.

Figure 5—Most Stolen Motor Vehicles in Canada in 2022

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Équité Association.

Ms. O’Brien also mentioned that “some insurers in the U.K. [are] deeming some vehicles on our top 10 list to be uninsurable, or their insurance is over 10,000 pounds a year.” In this regard, Celyeste Power, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC), noted that unlike in the U.K., insurers in Ontario and Alberta have to quote every single customer for insurance.

The committee recognizes that the financial burden of vehicle theft is widely spread. It imposes hardship on insurers who have no other resort than to raise insurance prime affecting Canadians across the country. It is in hopes of addressing insurers concerns that the committee recommends the following.

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada work in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments to find a balance allowing more freedom to insurers with regards to the insurance of the most stolen vehicles based on the United Kingdom model.

Mr. Jack raised CAA’s concerns that insurance premiums, deductibles, and overall auto-related costs would continue to rise if the rate of vehicle thefts is not brought under control. Mr. Jack further noted that the increase in vehicle thefts “are more than just a cost pressure for consumers, as important as that is”, but also has psychological effects on affected individuals.

Ms. Power said that in 2023, insurance premiums had increased by an average of $130 in Ontario and $105 in Quebec. Figure 6 shows the average cost of vehicle theft insurance claims from 2018 to 2023.

Figure 6—Average Cost of Vehicle Theft Insurance Claims in Canada between 2018 and 2023

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from the trade association named Insurance Bureau of Canada.

Ms. Aimers specified that the minimum deductible for multiple thefts in the last few years has reached $2,500.

Guillaume Lamy, Senior Vice-President, Personal Lines, Canadian Operations at Intact Insurance, added that insurance companies are paying out for claims, but that ultimately, it is the customers who pay for these costs through their insurance premiums.

Another financial implication of vehicle theft is the cost of law enforcement. Ms. O’Brien pointed out that “[f]rom a fiscal standpoint, there are significant costs incurred by the government in terms of law enforcement and administration of the criminal justice system, which affect all taxpayers.”

The financial implications of the rise in vehicle thefts not only affect individuals and the government, but also businesses. In this regard, Mr. Williams noted that the costs for securing dealerships were high, and the insurance costs were also increasing for dealerships. Mr. Williams also said that customers come to the dealerships to return their vehicles when their model is on the most stolen vehicle list out of fear of becoming a victim of violent crimes.

Chapter 2: Involvement of Organized Crime

Several witnesses noted that the increase in vehicle thefts may be attributable to the rise in organized crime. Comd. Desmarais stated that vehicle theft is of particular interest to criminal organizations given the vehicle shortage due to supply chain disruptions since the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, Mr. Lamy explained that criminals, including those in organized crime, “see vehicle theft in Canada as a low-risk, high-reward crime.”

According to Ch. Insp. Patenaude, “these organized crime structures that are going from the theft to the exportation overseas are very complex organizations, and they all have different roles and responsibilities in the organization.” During the visit to the Port of Montreal, the committee also heard that it is important to strengthen information sharing between the various law enforcement partners to focus on the leaders of these organized crime groups and disrupt their operations.

Scott Wade, Detective Inspector with the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), explained that vehicle theft is carried out by organized crime groups in major metropolitan regions using spotters to identify vehicles, thieves to steal them and runners to transport the vehicles to ports of export for Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Figure 7 illustrates the role and financial gain of each participant involved in vehicle theft.

Figure 7—The Hierarchy of Actors Involved in Vehicle Theft and Their Profit

Role of Organized Crime in Vehicle Theft

Damon Lyons, Executive Director of the Canadian Vehicle Exporter’s Association, explained that he believed the increase in organized crime was the driving force behind the surge in vehicle theft. He mentioned that a “recent report by Criminal Intelligence Service Canada stated that in just one year, between 2022 and 2023, they assessed there was a 62% increase in the number of organized criminal groups operating in the stolen vehicle market.”

In his brief, Mr. Lyons reaffirmed the major role organized crime plays in vehicle theft today. He noted that “[g]iven that the exportation process, vehicle manufacturer standards, vehicle recovery rates, and offender punishments have remained stable for well over a decade, the only new factor that can be added to the calculation is the involvement of organized crime.”

In his brief, Mr. Lyons noted that another factor explaining the rise in vehicle theft in Canada is that “[b]ad actors exploit federal regulations intended to allow for the regular flow of Canada’s massive trade variety of goods.”

In contrast to Mr. Lyons, Commr. Carrique was of the opinion that the vehicle theft problem and the involvement of organized crime were not new but dated back to the 1990s. According to him, the market for shipping stolen vehicles from Canada had decreased significantly in 2007 following the adoption of a “Transport Canada regulation[6] that mandated vehicle manufacturers to equip all new vehicles with anti-theft engine immobilizers.” However, organized crime found ways to circumvent anti-theft technologies while capitalizing on the vehicle shortage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This shortage also increased demand for used vehicles.

Commr. Carrique stated that according to him this surge in thefts in Canada is due to the ease with which thieves can obtain vehicles that are desirable overseas. Criminal networks make substantial profits by exporting these vehicles that are sold to buyers from Africa and the Middle East.

Many witnesses, including Commr. Carrique, said that the profits of vehicle theft are used to finance “other criminal activities ranging from drug trafficking and arms dealing to human smuggling and even international terrorism.”[7]

Several initiatives have been put in place to curb the involvement of organized crime in vehicle theft, including project RECHERCHER, which “targets criminal groups responsible for the export of stolen vehicles.”[8] These police initiatives will be discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3.

The committee recognizes that organized crime plays a significant role in the commission of vehicle thefts and that the real motivation for the organized crime is not necessarily the stolen vehicle, but the financial gains that such criminal activity generates. To limit the financial gain of organized crime, the committee makes the following recommendation.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada continue to strengthen Canada’s Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing regime, to address money laundering and proceeds of crime linked to vehicle theft.

Increase in Violence

Witnesses noted a considerable increase in acts of violence used to commit vehicle thefts. Ch. Insp. Patenaude noted that, even though vehicle theft is a property crime, the increase in violence used to commit theft raises issues of public safety.[9] He also pointed out that violence is often used to avoid being arrested by law enforcement. Comd. Desmarais observed a link between vehicle theft and gun violence. He said that the SPVM speculated that the profits generated by vehicle theft are used to acquire firearms.

Deputy Chief Johnson explained that violence can materialize as intimidation with firearms or breaking and entering. He also said that in 2023, 202 home invasion cases and 233 breaking and entering cases were reported in Toronto, representing a 400% increase. He further stated that as of 29 February 2024, since the beginning of 2024, 17 home invasions and over 32 carjacking occurrences had been reported in Toronto, which was double that of the same period last year.

Deputy Chief Milinovich noted that, over the course of the past two years in the Peel region alone, 185 carjacking incidents had been reported. He also said that home invasions are on the rise in the region as well.

Similarly, Mr. Adams explained that in Quebec and Ontario, thefts that are violent can be committed in the form of carjackings or home invasions. Mr. Brochet and Commr. Carrique said that the crimes are not only a threat to the public, but also to police officers in the course of their duties. Commr. Carrique specified that police officers are being threatened at gunpoint or being struck by violent offenders attempting to flee in stolen vehicles.

Mr. Williams said that violent thefts also occur at dealerships, reporting that employees have been held at gunpoint, pistol-whipped, or were victim of carjacked. He also mentioned that every dealership in Canada have a detailed security plan and protocols in place to prevent vehicle theft.

With regard to carjacking, Ms. O’Brien noted that

the criminals are becoming more brazen, often resorting to physical violence, as evidenced by the significant increase we've seen in carjackings, break and enters and owner-interrupted thefts that often result in violence. Greater Toronto area residents have witnessed a 104% increase in carjackings. Carjackings are terrifying.

She added that “[a]ccording to a recent Angus Reid survey, 84% of Canadians say the rise in auto theft makes them concerned about their safety and the increase in crime in their community.”[10]

Figure 8 shows the rate of increase in vehicle thefts related to more serious violations and the involvement of organized crime reported by police services between 2016 and 2023.

Figure 8—Involvement of Organized Crime in Vehicle Thefts in Canada between 2016 and 2023

Source: Table prepared by the authors using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table 35-10-0062-01 Police-reported organized crime, by most serious violation, Canada (selected police services).

Offenders Profile

Witnesses expressed concern over criminal organizations recruiting young people to commit vehicle theft. Moreover, Mr. Williams reported that criminal organizations are taking advantage of Canadian youth by paying them exorbitant sums of money to get involved in these crimes. Commr. Carrique said that there is a significant level of participation by young people, not only in committing vehicle theft, but in spotting and identifying the vehicles. In the Greater Toronto Area especially, many of these young people are armed, which puts public safety at risk.

Det. Insp. Wade explained that in Ontario, the average age of vehicle thieves is between 15 and 22 years, and he added that the accused are often “in possession of drugs, weapons, including firearms, and technological devices such as reprogrammed key fobs used to facilitate the theft of vehicles.” Lastly, Det. Insp. Wade said that 40% of the offenders arrested by the OPP were out on bail.

Deputy Chief Johnson reported that almost 50% of those arrested for carjacking in Toronto were repeated offenders and that a third of them were young offenders. Deputy Chief Milinovich added that in the Greater Toronto Area, “a large percentage of our carjackings are committed by people who have existing violent criminal records.”

In Quebec, specifically in Montreal, the trend seems to be different from that in the Greater Toronto Area. Comd. Desmarais said that, of the 550 arrests made by the SPVM in 2023, 50% of the individuals were between the ages of 15 and 25. Comd. Desmarais added that, in many cases, the young people arrested had no criminal record, so they were released, while Ch. Insp. Patenaude noted that criminal organizations also recruits “street gangs that have a history of violence [and drug trafficking].”

The committee heard several witnesses mention that youth outreach is crucial in reducing their involvement in criminal organizations that use them to commit vehicle thefts. Possible solutions will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Chapter 3: Complexity of the Port Environment

Witnesses reported that the complexity of the port environment in Canada contributes to the difficulty of intercepting stolen vehicles before they leave the country.[11] Anita Gill, Director of Health, Safety and Security at the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, explained the complexity of this environment by outlining the various roles of the parties involved:

One of the many regulations governing marine security is the Marine Transportation Security Act and regulations that outline the security roles and responsibilities within the marine environment. These regulations set out requirements for all port authorities and the requirements for independent marine terminal operators regarding the security of marine transportation and the protection of critical infrastructure.

Each of the 17 Canadian port authorities are responsible for implementing security measures within its jurisdictional boundaries, exclusive of leased spaces. The responsibility for security within those leased spaces falls to each independent terminal operator that has entered into a lease with that port authority.

The RCMP and CBSA are responsible for border protection and transnational crime, while municipal police agencies respond to calls for service from the terminals. Last, Transport Canada determines which categories of persons are required to have security clearances within the marine port environment. For the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority region, we have 29 different law enforcement and regulatory agencies that have a mandate on our port jurisdiction, and we have ongoing relationships with these agencies.

Figure 9 follows some of the steps taken by an exported container when it arrives at the port and illustrates the various roles and responsibilities of each participant involved in the port environment.

Figure 9—Role of Port Environment Stakeholders in the Export Process

Description: Figure 9 is an infographic representing the role of port environment stakeholders in the export process.

1. Transport Canada determines in its Marine Transportation Security Regulations the categories of persons who must hold a detailed security clearance.

2. Port authorities are responsible for ensuring the safety of people and goods transiting through the port (according to the Canada Marine Act). All access to the port is monitored and recorded.

3. While containers are stored at the terminal, CBSA officers inspect the documentation and exterior of the containers to ensure compliance (according to the Customs Act). CBSA officers may recommend further examination of at-risk containers through steps A or B below.

A) The HCVM: X-ray examination of the container using the HCVM to detect, notably, the presence of illegal goods and stolen vehicles.

B) Physical examination at the CBSA warehouse: In the event of non-compliance detected by the HCVM or in the documentation, a complete examination of the container is carried out by a CBSA officer.

4. When illegal goods are found, the CBSA calls upon appropriate services, such as the RCMP or local police services who begin the investigation.

5. Each terminal is leased by a private operator who is responsible for ensuring the security and for loading containers onto ships.

This chapter explores in greater depth the different aspects of the port environment, the problems identified, and the suggestions made by witnesses.

Legislative Framework

The Constitution Acts 1867 to 1982 assign the responsibility for ports to the federal government.[12] The Canada Marine Act (CMA), which received Royal Assent in 1998, provides for the establishment of Canadian port authorities (CPAs) and defines their powers. The CMA has for objective to make “the system of Canadian ports competitive, efficient and commercially oriented.” As explained by Félixpier Bergeron, Director of Port Protection and Business Continuity at the MPA, the CMA also establishes the responsibilities of the CPAs in terms of the management, operation, and maintenance of Canada’s ports.

In 1994, the Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA) was adopted, followed in 2004 by the Marine Transportation Security Regulations (the Regulations), giving port authorities responsibility for safety, order, and the port environment. Together, the CMA, the MTSA, and its Regulations, provide the legislative framework for Canada’s marine sector.[13]

The MTSA and its Regulations are largely influenced by the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS Code).[14] The IMO is “the United Nations specialized agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships.”[15]

Captain Allan Gray (Capt.), President and Chief Executive Officer of the Halifax Port Authority, explained that in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the IMO developed security measures specifically designed to combat terrorism. Following that, the IMO continued its work on improving maritime security in a holistic way, specifically by proposing the ISPS Code, which was adopted in 2004, and the IMO Code of practice on security in ports.[16] According to Capt. Gray, the IMO particularly useful tools for developing and implementing security strategies and identifying potential security risks in the port environment. Moreover, Capt. Gray mentioned that “[t]here is a call at IMO to broaden the scope of the ISPS code to consider organized crime. I would recommend that the Canadian representatives on IMO engage with and support this initiative.” To this end, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada recommend the International Maritime Organization to expand the scope of the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code to consider organized crime.

On another hand, Ms. Gill said that it would be important to amend the Regulations so as to “add more of a role in there for persons either at the marine terminals or at the port authorities so we could put in additional measures to assist law enforcement.” Currently, it allows port authorities to put security measures in place to protect Canada’s critical infrastructure, but it makes no mention of putting in measures for detecting or preventing criminality.

Considering the complexity of the port environment and the various pieces of legislation that could be amended to facilitate the work of stakeholders in the fight against vehicle theft, the committee makes the following recommendations:

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada work with public safety partners to identify high-risk Port facilities and conduct targeted security assessments for potential vulnerabilities, and that the Government of Canada revise and validate security plans for high-risk container facilities.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada review existing legislation and regulations, such as the Customs Act, with a view to:

- Enhance compliance with export controls;

- Increase accountability for all partners and facility operators involved in export operations;

- Increase penalties for non-compliance and false reporting; and

- Benefit from international best practices.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada assess legislation to ensure export regulations are effective for law enforcement.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada allow port authorities to put security measures in place to prevent criminal activity.

Role of Port Authorities

CPAs are single legal entities that operate independently from the federal government. Each of the CPAs is governed by a board of directors whose members are nominated by port user groups and various levels of government. CPAs operate according to business principles and have the authority to determine their own strategic direction and make commercial decisions based on their needs. They are financially self-sufficient and act as landlords by assuming responsibility for the maintenance of the port and commercial shipping channels. CPAs can therefore lease out port operations to private terminal operators.[17]

When visiting the Port of Montreal, the committee learned that each terminal has a designated origin and destination, and that two ships can be docked at each terminal at the same time. Although security falls under the jurisdiction of the MPA, terminal tenants can set up their own security systems on the terminal they are leasing.

In a brief submitted to the committee, the Association of Canadian Port Authorities (ACPA) described ports as “complex operating environments” given the various relationships between the organizations working there. The ACPA noted that “[t]here are important distinctions between the roles and responsibilities of the port authority itself, versus the roles of independently owned and operated tenants and port users, government agencies and police of jurisdiction.” Mr. Baudry said that the MPA’s focus was on the fluidity and the security of the port sites.

Mr. Bergeron explained that the CMA delegated specific and limited responsibilities to the CPAs regarding the security of the spaces under their authority.[18] For example, this responsibility includes the safety of people and goods passing through the port but does not include the goods inside the containers.

Role of Transport Canada

Ms. Gill and Mr. Bergeron stated that the security clearance program is managed by Transport Canada. As such, Transport Canada determines which categories of persons are required to have security clearance within ports and marine facilities and conducts these checks.

Reviewing the Security Clearance Process

Witnesses noted a gap in security clearances at Canadian ports. Some witnesses called for greater control over security accreditation of employees and review of the relevant regulations.[19]

Ms. Gill explained that, “[a]s per the Transport Canada regulations, it’s a requirement for everybody entering a cruise facility to have a security clearance,” but that this requirement differs at container terminals. Mr. Bergeron specified that “[b]asically, [security clearance is] reserved for people having authority over other people or people having authority with regard to the management of the inventory.” He explained that at the Port of Montreal, of the 1,200 longshoremen, only 200 of them have security clearance. Ms. Gill added that at the Vancouver Fraser Port, of the 32,000 port passes, only 7,000 are required to have security clearances.

According to Mr. Brochet, it is necessary to review the Regulations, take firmer action, and adopt new legislative standards with respect to the selection processes and security accreditation systems for all Canadian port employees. Ch. Insp. Patenaude and Mr. Brochet mentioned the possibility of giving police the task of conducting security checks of CPA employees. Police services, such as the SQ, already have the capacity to carry out security clearances and can ensure rigorous, impartial background checks on employees.

In addition, Capt. Gray pointed out that security clearance cards at Canadian ports were not the same between different ports since each port creates its own access card. He stated that “[t]he inconsistencies make the system vulnerable to fraud. Other jurisdictions have centralized systems with standardized cards, which make it easier to detect forgery and compare a card against a centralized database.”

Capt. Gray emphasized that a centralized system, like those found in other jurisdictions, would avoid this security gap. He explained that other countries affix security hologram films on their access cards that can be purchased only from the government. This means that the cards are identical throughout the country, making it easier to detect forgeries.

Capt. Gray supported the federal budget’s proposed funding for Transport Canada and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to create a centralized transportation security clearance program.

Like many witnesses, the committee is concerned by the issue of gaps in the security clearance process of Canadian ports. To that effect, it therefore makes the following recommendations:

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada explore legislative amendments to provide police services with the authority to conduct security clearances for all Canadian Port Authorities’ employees.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada improve and standardize the security clearance screening of Canadian ports carried out by Transport Canada in collaboration with police services by:

- establishing a centralized database for employee access cards for all Canadian ports;

- establishing a mechanism to standardize authentication of access cards across all Canadian ports; and

- considering technology used elsewhere in the world, like holographic film technology.

Role of the Canada Border Services Agency

Aaron McCrorie, Vice-President of Intelligence and Enforcement at the CBSA, highlighted CBSA’s dual mandate “to facilitate legitimate trade in support of a strong Canadian economy and to ensure border security and integrity to protect Canadians from a variety of threats including illegal drugs, firearms and the export of stolen vehicles.”

During the Port of Montreal visit, the committee learned that when imported containers arrive at the port, CBSA officers must check the documentation and the exterior of the containers to ensure compliance. No accurate data were available as to the percentage of containers searched when exported. However, CBSA officers confirmed that exported containers are occasionally searched for drugs, firearms, and stolen vehicles, among other things. The CBSA officers also explained that since the increase in vehicle thefts, they have been paying special attention to the inspection of export containers.

Under section 6 of the Customs Act, the port authority shall provide, equip, and maintain adequate buildings and other facilities for the proper inspection of containers by CBSA officers.

The CBSA has high-tech tools available for inspecting containers, including Ionscan, which detects narcotics and explosives. The CBSA also has an X-ray imaging system, commonly referred to as the HCVM (Heimann Cargo Vision Mobile), which allows for fast and non-intrusive examination of a container’s contents.

The HCVM is primarily used to investigate containers that are imported, either when a container seems suspicious, when it has been randomly selected, or when a request has been made by an authority. It can also be used to examine export containers, although less frequently. If non-compliant elements are found during this X-ray examination, the container is brought to the container searches centre for a complete inspection by CBSA officers.

When a container inspection leads to the recovery of a stolen vehicle, a complete examination of the vehicle is carried out. This examination is a way to detect the presence of drugs, weapons, or other illicit goods. Currently, fentanyl is the main opioid intercepted by the CBSA.

Mr. McCrorie offered an overview of CBSA’s approach towards its dual mandate and the work it accomplished in 2023. He explained that throughout all Canadian ports where CBSA operates, the CBSA facilitated the movement of over 3.5 million containers, it protected Canada’s communities by preventing over 900 prohibited firearms and over 27,000 weapons from entering the country, and it intercepted over 72,000 kilograms of prohibited drugs, cannabis, narcotics, and precursor chemicals. Lastly, the CBSA prevented 1,806 stolen cars from being exported.

Mr. McCrorie added that at the time of his testimony, the CBSA had already intercepted 949 stolen vehicles in 2024. He also said that the CBSA continued to work with “the [RCMP], the [OPP], the [SQ], the [SPVM] and other police of jurisdiction to strengthen information sharing and support their criminal investigations.” For example, in 2023, the CBSA participated in 14 different police operations, including Project Vector, a joint operation between the CBSA, the OPP, the SQ, the SPVM and Équité Association, which resulted in 390 shipping containers being targeted and the recovery of a total of 598 stolen vehicles as of 15 April 2024.

Mr. McCrorie also noted that the CBSA worked in collaboration with industry groups like Équité Association and the Canadian Vehicle Exporter’s Association to further improve the CBSA’s targeting efforts.

Reviewing the Canada Border Services Agency’s Priorities

The committee heard on numerous occasions that the CBSA’s mandate was more focused on imports than exports. Mr. Brochet, Mr. Jack and Deputy Chief Milinovich noted that the CBSA did not appear to be inspecting export cargoes. Deputy Chief Milinovich said that despite the high number of stolen vehicles being exported out of the country, the CBSA did not have officers or analysts exclusively assigned to intercepting the export of stolen cars from the country. In this regard, Deputy Chief Milinovich stated that “[w]e need to resource and equip our ports in a way that is commensurate with the pressure and issues we are experiencing.”

In terms of the CBSA’s mandate and the export of goods, Capt. Gray noted that it was important to understand “that most customs authorities around the world are focused on protecting a country and looking at goods coming in. … [T]heir primary focus is about protecting a country, so their resources are allocated that way.” He believes that the current resource allocation does not allow the CBSA to focus sufficiently on exports.

Similarly, Mr. McCrorie said that the CBSA mainly focuses its efforts on threats coming into Canada, such as drugs and illegal firearms. In his view, this does not mean that the CBSA is ignoring exports. Rather, it is a question of balancing its priorities and the risks detected.

With respect to balancing priorities, Mr. McCrorie explained as follows:

Our mandate, both in terms of looking at traffic coming in, whether it’s people or goods, or traffic leaving in terms of exports, is to always take a risk-based approach. We can’t check every person. We can’t check every container. We can’t check every ship or every truck. However, by taking a risk-based approach, we’re making effective use of the resources that have been allocated to us by the people of Canada.

Nevertheless, Mr. Brochet, proposed a restructuration of CBSA’s operations so that it could significantly increase audits of export containers. He suggested that the CBSA be required to carry out a certain percentage of random inspections of container contents because, to his knowledge, the CBSA checks only the containers it receives information on regarding potential illegal activities. Mr. Brochet said that the type of new obligations would require additional resources and a review of the CBSA’s methods.

Mr. Jack also said that there needed to be a mentality shift at the CBSA—it needed to focus more on exports. Meanwhile, Deputy Chief Milinovich also stressed the need to review relevant legislation such as the Customs Act and the Export and Import Permits Act.

Considering the testimony heard, the committee recognizes the need to review the CBSA’s priorities so that the agency can give greater priority to export containers and that resources be allocated to it in this regard. To that effect, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada review the export surveillance aspect of the Canada Border Services Agency's (CBSA) mandate by:

- requiring a minimum percentage of random examinations of export containers at Canadian ports;

- allocating more resources to this aspect of the CBSA's mandate; and

- introducing legislative amendments and regulations to compel rail and port operators to provide adequate accommodations for the examination of exported containers by CBSA officers.

Maintaining the use of X-ray Technology

Capt. Gray explained that, according to the standard practice around the world, including in Canada, “there is no X-ray or scanning of export boxes unless the country of destination has a security requirement for a preload scan.” He is of the opinion that “spending a lot of money on scanners may not fix the problem, and scanning every single container may not fix the problem.”

Mr. Bergeron spoke about some important aspects related to the use of technological equipment, such as the HCVM, which emits radiation to scan the containers. He noted that it would be best to assess the health risks to workers associated with radiation. He pointed out that although this technology is used more frequently in other parts of the world, “in those places, they don’t have the same commitment to human life that we do in Canada.” He also noted that it would be necessary to assess whether there is enough space to use them and whether the use of this technology would affect the port’s efficiency. He explained that this technology “takes between four and five minutes to scan each container.”

Mr. McCrorie explained that approximately 2,300 containers a day transit through the Port of Montreal, but that the X-ray technology currently available to the CBSA allows it to search only around 10 containers per hour.

If we had 10 screening devices, we could do all 2,300 in a day, but that doesn’t account for the backlog that would occur with vehicles lining up and trains lining up. It’s just physically impossible to search every container. That’s why it’s so important to leverage information and intelligence and do our targeting.

Mr. McCrorie reported that, for a while, most of the stolen vehicles were recovered through police tip-offs, but that nowadays, about 70% of the stolen vehicles recovered by the CBSA are found through CBSA’s own targeting work. The other 30% are found through police tip-offs. The CBSA carries out this work using targeting and information management techniques it obtains as part of export declarations, which includes VINs. He deems that it would be preferable to consider other solutions than scanning more containers, such as leveraging information and intelligence as well as targeting technics.

When it comes to the effectiveness of scanning export containers, Capt. Gray said that this approach is not entirely foolproof. For instance:

[I]f the manifest says the box contains household goods but a scan reveals a car inside, then it’s reasonable that enforcement agencies know they should be inspecting the container. But if they scan a box that has a car inside, and the manifest says there is a car inside, there is no way of knowing if that car is stolen without opening the container and looking to see if the VIN matches the ownership documents. Even that check might not catch a VIN that has been tampered with.

This means that scanning a container would only help detect undeclared vehicles but would not effectively identify vehicles that have been revinned. He added that it is not realistic to scan every single container or even the majority of them. Capt. Gray therefore questioned spending a lot of money to buy scanners as a possible solution.

The committee recognizes the effectiveness of scanning export containers but understands that it is not realistic to use this technology on all export containers. It further recognizes that the CBSA’s targeting expertise is important and that the agency provides excellent support to police investigations when their assistance is requested. For these reasons, the committee makes the following recommendations:

Recommendation 11

That the government of Canada enhance collaboration between the Canada Border Services Agency and port authorities, rail network, and shipping partners to expand export cargo container examinations, notably to include urgent, significant, and random deployment of scanning and detection technology in new locations.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada continue to provide adequate resources to the Canada Border Services Agency to maintain their 100% response rate in conducting container examinations when information is provided by law enforcement agencies.

Increasing Funding

Mr. McCrorie highlighted the $28 million federal investment announced at the Summit by the Minister of Public Safety, Democratic Institutions and Intergovernmental Affairs to combat the export of stolen vehicles. In a news release, the CBSA announced that this funding would, among other things, increase the CBSA’s capacity to detect and search containers with stolen vehicles, as well as test available detection technologies, such as advanced analytical tools like artificial intelligence (AI), that could support the work of CBSA officers in intercepting export containers.

Witnesses such as Ms. Gill and Mr. Adams applauded the Government of Canada’s announcement of increased funding for law enforcement resources, including supporting the CBSA’s work at Canada’s ports.

However, other witnesses, such as Mr. Lamy, were of the opinion that continued investments in the CBSA are critical. For example, Brian Kingston, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association, stressed the need to support the CBSA through “investments into personnel, container imaging machines and remote VIN verification technologies.”

With regard to staff shortages, Mark Weber, National President of the Customs and Immigration Union, suggested opening a second college to train CBSA officers. He noted that there is currently no shortage of applicants, but rather a shortage of resources to train them. He is of the opinion that “[t]echnology can be very helpful to an officer, but you need the officer there.”

Mr. Jack suggested providing the necessary resources to the CBSA “by upping boots on the ground, installing cargo container scanners and prioritizing random inspections on exports, which today are virtually non-existent.”

The committee understands the need for continued investments in the CBSA to ensure that the agency has the resources it needs to meet the expectations of Canadians. The committee therefore recommends the following investments:

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada invest in combating vehicle theft by:

- Increasing the complement of border officers by hiring new frontline officers and deploying them to ports, rail yards, and intermodal hubs to expand examination capacity in response to intelligence developed by the Canada Border Services Agency and law enforcement;

- Dedicating new resources to intelligence and targeting capabilities specific to stolen vehicles; and

- Identifying and testing new detection technology tools to expand capacity to screen containers for stolen vehicles.

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada decrease spending on outside consultants at the Canada Border Services Agency and divert that money towards increasing scanning capacity at Canada's ports.

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada open a second Canada Border Services Agency training college.

Role of Canadian Police Services in Ports

The committee heard that the role of Canadian police services was critical in the fight against vehicle theft. During the visit to the Port of Montreal, the committee was also told that when illegal goods are retrieved, the CBSA called on intelligence services and then on the RCMP and local police services, who are responsible for contacting the appropriate foreign authority or the provincial police services, to coordinate further investigation.

In certain circumstances, the police service of jurisdiction may decide to proceed with a controlled delivery of the container with the illicit goods or stolen vehicle. The police officers explained to the committee that a controlled delivery involves proceeding with the planned delivery of the container, notably by reducing or replacing the goods, allowing for arrests to be made when the container is retrieved.

Considering the important and ongoing role of various police services in ports, the committee makes the following recommendation:

Recommendation 16

That the Government of Canada continue to commit to supporting the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and other police services by ensuring they have the necessary tools to gather information and make arrests against organized crime.

Collaboration at the Port of Montreal

According to several witnesses, “[c]ombatting vehicle theft requires co-operation among [police services] organizations, governments, industry and international partners.”[20] Comd. Desmarais noted the SPVM’s collaborative efforts with its partners:

At the SPVM, our priority has always been to work with our partners. In 2022 and 2023, we continued to build on this approach, which has always produced excellent results. After discussing with our partners at the Canada Border Services Agency or CBSA, the SQ, the Ontario Provincial Police or OPP, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or RCMP, and the Equity Association, we decided to pursue that approach further.

Comd. Desmarais also stressed the need to continue working closely together from a national perspective to reduce the criminal organizations’ activities.

Similarly, several witnesses highlighted the police operations carried out in collaboration with various partners to reduce vehicle theft and curb organized crime activities, including:

- Project VECTOR: Assistant commissioner and Regional Commander Matt Peggs (A/Commr.), of the RCMP’s Ontario Division, said that the RCMP was involved in Project VECTOR, which targets the criminal supply chain of stolen vehicles. He added that on 3 April 2024, the project led to the recovery of 598 vehicles at the Port of Montreal. Mr. McCrorie said that the project was a joint operation between the CBSA, the OPP, the SQ, the SPVM and Équité Association.

- Project EMISSIONS: Det. Insp. Wade said that Project Emissions allowed for the collection and sharing of vehicle theft crisis information with police services nationally and internationally.

- Virtual interprovincial and cross-border intelligence team on the export of stolen vehicles: Ch. Insp. Patenaude said that “a virtual interprovincial and cross-border intelligence team on the export of stolen vehicles has been set up using resources from the [SQ], the [OPP], the [RCMP], and the [CBSA].”

- Tag stolen vehicle tracking system[21]: Mr. Bergeron mentioned that the MPA was working with private companies “that monitor or track stolen vehicles in the port using the famous Tag stolen vehicle tracking system.” Antennas were installed at the Port of Montreal for this purpose. He also told the committee about the launch of a national program to welcome all companies operating in the field of technology similar to these antennas.

Collaboration at the Port of Vancouver

According to Ms. Gill, “port security and port policing exist on a continuum, and enhanced information sharing between [police services] and port authorities is essential.” In this regard, she mentioned the collaboration between various partners at the Port of Vancouver, including:

- PIMSWG: Ms. Gill highlighted the success of the PIMSWG, which operates at the Port of Vancouver. This initiative includes senior leadership from regional Transport Canada, RCMP, CBSA, Vancouver Police Department and Delta Police Department.

- Training on the inner workings of the Port of Vancouver: Ms. Gill said that senior RCMP officers had reported the need to better understand the port’s operations in order to intervene more effectively. The Port of Vancouver therefore offered a two-day training course in co-operation with the RCMP’s Federal Serious and Organized Crime division, Pacific region, and CBSA Operations and Intelligence, Pacific region.

Enhancing the Police Ability to Search

In addition to collaboration, increasing police officers’ powers to conduct searches could facilitate vehicle theft investigations. Comd. Desmarais explained that the various police services can conduct container searches with legal authorization: “We state what the ongoing investigation is and open the containers together.” However, he believed that giving additional powers to open containers to police officers working at the port “whether they are from the [SQ], Montreal city police, or other police services … would certainly facilitate matters.” Ch. Insp. Patenaude added that the SQ had been working with the SPVM and the CBSA since March 2022 to enhance their ability to search containers.

However, Mr. Bergeron explained that the local police jurisdictions all across the country could have access to the Port of Montreal if they asked for it, “but they couldn’t open a container by themselves. The CBSA or the RCMP needs to be there, because they are the only two that can open a container under the Customs Act.” Mr. McCrorie added that, as opposed to the police jurisdictions, the CBSA has the power to open containers without a first obtaining a warrant. Mr. Bergeron stated that the MPA granted the CBSA and the RCMP, as well as other police services, an ongoing 24-hour access to the Port of Montreal, which extends to the terminals and to more than 600 cameras monitoring the entire Port.

Mr. Bergeron pointed out that no police jurisdictions had applied for access to the Port of Montreal, but that the OPP carried out a joint vehicle theft investigation with the SPVM, which is the police of jurisdiction. He explained that “[i]t’s a question of territorial jurisdiction, but if they demand access, they will grant them access. They can then get into the terminal, assess what it is and where they want to find something, and then call in the CBSA to open the container.”

With regard to the physical capacity to inspect containers, Comd. Desmarais noted that there is naturally less space designated for searching export containers than for import containers at the Port of Montreal, which prevents them from doing more.

The committee commends the collaborative work between the police services, the CBSA and the port authorities. It recognizes the important work of the police services in the fight against vehicle theft. However, it cannot ignore the existence of obstacles to the work of police services in the port environment. The committee makes the following recommendations with the objective of countering some of these obstacles.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada work with provinces, territories, and municipal partners to provide additional funding to police services to improve their capacity to provide timely referrals, information, and actionable intelligence to the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), as well as take custody of stolen vehicles intercepted by CBSA.

Recommendation 18

That the Government of Canada amend the Customs Act to make changes to the conditions under which containers may be searched and expand the powers of police officers working at ports to open containers when they suspect fraudulent contents.

Containers Security

Capt. Gray explained that

[t]ypically, a shipping container is packed at an off-site location. The paperwork is done. That includes a self-declaration of what's inside. The container is closed and marked with a customs seal. When a container arrives at a terminal by either truck or rail, the container number is matched to the booking number, the customs seal is physically checked to see that it hasn't been broken, the serial number of the seal is noted against the container and then the container is put in the stacking area for export. Neither the terminal operator nor the port authority have the right to hold or open a container unless directed by the shipper, the shipping line or the CBSA.

He added that in terms of documentation accompanying a container, “there is a bill of lading, which is a legal contract between the shipper and the carrier that shows ownership, and there is a cargo manifest, which lists the contents of what is claimed to be inside the box.” The manifest document includes words like “said to contain.” No one other than the exporter who filled the document and the container knows for sure what is in it.

Mr. Bergeron also explained that the CPAs and the terminals do not have access to information about the containers’ content. “The only people who do have access to that information besides the exporter are the customs officers and the vessel operators.”

Mr. Bergeron pointed out that although the MPA do not have the authority to inspect containers, initiatives have been launched to support police and businesses that conduct investigations. In this regard, he said that the MPA has given access to 800 police and customs officers, including RCMP, SQ, SPVM and CBSA officers, to the Port of Montreal at any given time. In addition, more than 600 cameras were installed at the port to ensure better monitoring. He stated that “access to the port is monitored 24 hours a day, seven days a week, at all times. Any access to the port is monitored and logged.”

Mr. Baudry stated that the MPA also intensified its communication efforts to facilitate mutual understanding between the Port and the police. Capt. Gray said that it is vital for CPAs to “work closely with their partners, including local police, federal enforcement authorities and the [CBSA] to achieve security.”

Amending the Rules Associated with the Export Manifest

According to Mr. Bergeron, a major problem stems from the regulations surrounding the export manifest. He said that “there is no accountability on who stocked the container. The paperwork, once they sign off and it is sent to CBSA, is the end of it, but there is nobody who signs off by saying what is in the container for real.” Mr. Bergeron noted that the Regulation and legislation needs to be amended to add some form of accountability with respect to the validity of the content declared to be in the container.

Mr. Brochet suggested “to force carriers to ensure that the container contents match the container manifest. In other words, they need to be liable for what they carry”. In that regard, Mr. Bergeron said that currently, container carriers “don’t have liability because the container is sealed.” He is of the view that the person who put the seal on the container is the weakest link in the chain because “there is no responsibility for that.”

Witnesses also highlighted a problem regarding the possibility of amending an export manifest after the departure of a ship.[22] Ms. Power noted that in Canada, export documents can be amended after a ship had set sail, compared to the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency that requires “the exporter of a vehicle to present all export documents and the vehicle at the port at least 72 hours prior to export.”

Mr. Lyons said that the system in place since 2005 requires the manifest to be presented within 48 hours of departure for anything that leaves by a vessel. Ms. O’Brien and Mr. Lyons were of the opinion that this standard should be modified to include the 72‑hour rule established in the U.S. Mr. Lyons stated in his brief that

[i]n consultation with industry, Canada should explore the feasibility of requiring shipping lines to only amend prescribed Bill of Lading data when the [Canadian Export Reporting System Portal] declaration has been properly amended with CBSA. This will provide greater data to CBSA for its targeting intelligence, as well as create a greater risk to organized crime in the falsification of their data and documents.

Comd. Desmarais also sustained that a period of 72 hours would be favourable to CBSA and police investigations, as it would give them greater flexibility to perform checks. Mr. Lamy explained that introducing the 72-hour rule as an export requirement “would allow for more vehicles to be searched prior to export, and ensure the actual VIN matches what is declared on the export declaration form.”

The committee was surprised by the shortcomings surrounding the rules associated with the export manifests. Therefore, it makes the following recommendations in the hope that their implementation will contribute to improving export standards and facilitate the work of detecting stolen vehicles.

Recommendation 19

That the Government of Canada review the Customs Act and its regulation to impose an obligation of veracity on the export document submitted to Transport Canada and ensure the imposition of substantial penalties in the event of false declaration on the container manifests.

Recommendation 20

That the Government of Canada amend the Customs Act and its regulation to prohibit the alteration of export manifests after the departure of vessels and require the presentation of export documents at least 72 hours before departure.

Using Artificial Intelligence Technology in the Port Environment

Some witnesses proposed using AI technology to make it easier for the CBSA to target and inspect containers. For instance, Mr. Baudry said that the MPA was looking at new technologies to facilitate the detection of containers carrying stolen vehicles. While some witnesses called for more X-ray inspections of containers, others raised the possibility of using new technologies such as AI.

Mr. Lyons believed part of the government’s $28 million in funding should be invested in AI development as it would support the analysis of submissions in the Canadian Export Reporting System. In his brief submitted to the committee, Mr. Lyons explained that criminal organizations often make misrepresentations in their declarations. The CBSA could take the following measures:

- VIN verification via decoding;

- automated VIN duplication checks;

- automated checks of the national stolen vehicle database;

- the creation and automated checks of a true national vehicle lien database; and

- automated comparisons of integrated data sets deemed most relevant to targeting suspicious activity.

Mr. Lyons stated in his brief that the CBSA could draw inspiration from the efforts of the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre, which announced investments in AI as a means of targeting. He believed that there were too many containers to open every single one of them, “but with their intelligence, we would know who is shipping this product and if that’s actually what’s inside of that container. It’s about gathering all that intelligence to know where we should target our efforts.”

Ms. Gill also argued that “[t]here are many implications of installing X-ray machines, like resourcing and additional potential responsibilities on CBSA and the terminal operators.” She also said that AI could make it easier to identify containers to examine by comparing the manifest to the contents of the container. She said that the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority would be willing to discuss the best way to integrate these technologies.

Considering the rapid progress in technology such as AI and the benefits it represents for ensuring containers security, the committee makes recommendations in favour of investing and using these technologies.

Recommendation 21

That the Government of Canada integrate the use of advanced data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) to better target containers with suspected stolen vehicles and that the Canada Border Services Agency utilizes AI to facilitate the verification of Vehicle Identification Numbers and the Canadian Police Information Centre.

Recommendation 22

That the Canada Border Services Agency undertake the following measures:

- Verify the vehicle identification number (VIN) by decoding;

- Improve targeting techniques and verification of export declarations;

- Implement automated VIN duplication and national stolen vehicle database checks (Canadian Police Information Centre); and

- Improve analysis of submissions to the Canadian Export Reporting System. 4

Chapter 4: Suggestions to Combat Vehicle Theft

Throughout this study, the committee heard many possible solutions to combat vehicle theft. While the committee recognizes that there is not only one solution to this complex issue, it acknowledges the importance of diversifying approaches. In addition to the suggestions specific to the port environment discussed in Chapter 3, the section below explores other suggestions put forward by witnesses.

Raising Public Awareness

Raising public awareness is an important aspect of vehicle theft prevention, whether with consumers, young offenders, or dealers. CAA and CAA Insurance provided recent data in their brief on security measures currently taken by consumers:

- Only 80% of drivers lock their car doors.

- Just over 1/3 of drivers keep their vehicle in a garage.

- Just 20% of drivers have motion sensors or a video camera for their driveway or garage.

- Only 5% of drivers use either a Faraday pouch or a steering wheel lock.

- There is considerable opportunity to change habits—very few drivers actively park their lesser-valued vehicle at the bottom of their driveway.[23]

According to Ms. Power, focusing our efforts on prevention and consumer awareness to make vehicles harder to steal is a first step that should not be overlooked.

Ms. Power and other insurer representatives, such as Mr. Lamy and Mr. Jack, noted the efforts made to date by insurers to encourage consumers to better protect themselves against vehicle theft. For instance, Ms. Power highlighted the awareness efforts made by IBC and the industry in general:

When it comes to elevating consumer awareness, insurers are doing their part. In addition to consumer education at the point of sale by brokers and agents and incentivizing the installation of aftermarket anti-theft devices, our industry ran an “End Auto Theft” campaign last fall to educate drivers on what they can do to protect themselves. We reached tens of millions of drivers.

Ms. Power explained that her organization advises consumers to install a bar on the steering wheel or put their keys in a Faraday bag.[24] Mr. Jack noted that CAA also provides the same type of advice to consumers.

According to the brief submitted by CAA and CAA Insurance, more specific awareness campaigns in high-risk areas, such as “Lock It or Lose It” in Alberta, serve to remind residents to take the simple step of locking their vehicles all the time.

Mr. Lamy stated that Intact Insurance works closely with provincial regulators to raise awareness around theft trends, partners with companies such as Tag to offer Intact customers the opportunity to install aftermarket tracking devices on their vehicles, and supports communication efforts through their brokers to encourage customers to protect their vehicles.

Comd. Desmarais and Mr. Adams noted the use of the media as a means for raising awareness. In this regard, Mr. Adams said that his organization has been developing a website to raise consumer awareness on vehicle theft and provide information to victims of this type of crime.

Several police representatives also expressed the need to focus on prevention among young people who are often targeted by organized crime groups wishing to take advantage of their vulnerabilities.[25] Comd. Desmarais explained that these young people, who often have no criminal record, are easily tempted by the money they can make from stealing vehicles, but that they do not always understand the reality. Comd. Desmarais provided the example of young people who “film themselves inside the vehicles while being followed by the police to make fun of the situation. As Mr. Patenaude said earlier, we need to focus on educating those young people, while also focusing on enforcement.”

Along the same lines, during the visit to the Port of Montreal, the committee heard that to reduce the involvement of at-risk youth in vehicle theft, it is important to target the leaders of organized crime networks.

The committee recognizes that public awareness and community initiatives are important aspects of vehicle theft prevention, not only for vehicle owners, but also to help prevent the recruitment of at-risk youth by organized crime and gangs. The committee hopes that the implementation of the following recommendations will help strengthen the resilience of Canadian communities to vehicle theft.

Recommendation 23

That the Government of Canada continue to invest in community-based prevention initiatives for youth-at-risk of future involvement in the criminal justice system, including by prioritizing the funding of new project under the Youth Gang Prevention Fund for community-based initiatives preventing at-risk youth from joining gangs and from getting involved in other criminal and anti-social activities, such as youth delinquency, vehicle theft, substance use, and gun violence.

Recommendation 24

That the Government of Canada continue investing in the Initiative to Take Action Against Gun and Gang Violence to address the increased links between gun and gang violence and vehicle theft.

Recommendation 25

That the Government of Canada collaborate with provincial and municipal governments to develop a national awareness campaign focused on vehicle security best practices, aimed at educating the public on preventative measures to reduce the risk of vehicle theft.

Recommendation 26