PROC Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

The Inclusion of Indigenous Languages on Federal Election Ballots: A Step Towards Reconciliation

Introduction

Pursuant to Standing Order 108(3)(a)(vi),[1] the mandate of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (the Committee) includes the review of and report on all matters relating to the election of members to the House of Commons.

On 14 December 2021, the Committee adopted the following motion:

That the committee conduct a study about the addition of Indigenous languages on federal ballots for general elections.[2]

This is similar to another motion that was adopted by the Committee at its last meeting of the 43rd Parliament.[3] Given the dissolution of the 43rd Parliament in the weeks following the adoption of this motion, such a study could not be initiated by the Committee at that time.

The Committee began its study on the addition of Indigenous languages on federal ballots on 29 March 2022. During the course of its study, the Committee heard from 17 witnesses over four meetings. The Committee wishes to sincerely thank all the witnesses who participated in this study for their valuable contribution.

Background

A. Barriers For indigenous people to electoral participation

In undertaking this study, the Committee recognizes that the ongoing legacy of colonialism in Canada has affected the participation of Indigenous people in federal electoral politics. Notably, the Committee heard that “residential schools have had a long list of enormous intergenerational impacts.” [4] One of those impacts is the constant erasure of the languages of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Decades of attempts to assimilate them into the broader Canadian society, as well as related colonial policies, may have disconnected Indigenous people from Canada’s institutions and electoral processes.

Ms. Karliin Aariak, Commissioner, Office of the Languages Commissioner of Nunavut, argued that federal departments and agencies such as Elections Canada have a role to play in the revitalization, promotion, and preservation of Indigenous languages.[5] She also noted that Nunavut’s Inuit Language Protection Act

[Deplores] the past government actions and policies of assimilation and the existence of government and societal attitudes that cast the Inuit Language and culture as inferior and unequal, and acknowledging that these actions, policies and attitudes have had a persistent negative and destructive impact on the Inuit Language and on Inuit.[6]

Marjolaine Tshernish, General Manager of the Institut Tshakapesh, noted that Indigenous people had to wait almost a century after Confederation before getting the right to vote.[7] For instance, Aluki Kotierk, President of Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., indicated that, despite getting the right to vote in 1950, “it wasn't until 1962 that all Inuit communities actually had access to voting services.”[8] Being excluded for so long from the process probably had an impact on turnouts today, according to Ms. Tshernish.[9]

According to Allison Harell, professor of political science at the Université du Québec à Montréal,

[I]t is important to recognize that Canada's colonial history means that we need to ensure that [I]ndigenous people can participate on their own terms in our electoral processes while acknowledging that some may not see the electoral process as either legitimate or their own. Making ballots multilingual could be a step to increase the legitimacy of the electoral process for these electors, and perceptions of legitimacy not only support broader participation but are also important for the health of our democratic system.[10]

Similarly, Ms. Kotierk stated that,

Supporting [I]ndigenous peoples in Canada and the right to vote in their own language could be an important step towards the goal of reconciliation. It would help us feel as [I]ndigenous people that we are an important part of the democratic system. It would demonstrate respect for our language, our culture and our world view as a self-determining people. We would have a stronger sense of our ownership in Canadian democratic institutions, which would provide a stronger foundation for Canada to move forward with [I]ndigenous peoples and make Canada stronger.[11]

In presenting this report, the Committee wishes to acknowledge the ongoing effects of colonialism on Indigenous participation in electoral processes, both as candidates and voters.

B. Indigenous languages in Canada

There are currently over 70 Indigenous languages spoken in Canada, with considerable variation in the number of speakers of each language. As well, there is a significant gap between the number of Indigenous people in Canada and those who can speak an Indigenous language.

According to the 2016 Census, only 15.6% of the Indigenous population in Canada has the ability to conduct a conversation in any of these languages.[12] This can be explained by the many events that have affected the vitality of Indigenous languages, particularly the residential school system. Furthermore, only 12.5% of the Indigenous population reported an Indigenous mother tongue in 2016; this means that, for a number of speakers, an Indigenous language was learned as a second language.[13]

Indigenous languages can be divided into 12 distinct language families. Table 1 shows the Indigenous identity population who can speak an Indigenous language, by language family, as well as the main provincial and territorial concentrations of these speakers.

Table 1–Indigenous Identity Population Who Can Speak an Indigenous Language, by Language Family, and Main Provincial and Territorial Concentrations, 2016

Indigenous language families |

Population |

Main provincial and territorial concentrations |

Algonquian languages |

175,825 |

Manitoba (21.7%), Quebec (21.2%), Ontario (17.2%), Alberta (16.7%), Saskatchewan (16.0%) |

Inuit languages |

42,065 |

Nunavut (64.1%), Quebec (29.4%) |

Athabaskan languages |

23,455 |

Saskatchewan (38.7%), Northwest Territories (22.9%), British Columbia (18.4%) |

Salish languages |

5,620 |

British Columbia (98.8%) |

Siouan languages |

5,400 |

Alberta (74.9%), Manitoba (14.2%) |

Iroquoian languages |

2,715 |

Ontario (68.9%), Quebec (26.9%) |

Tsimshian languages |

2,695 |

British Columbia (98.1%) |

Wakashan languages |

1,445 |

British Columbia (98.6%) |

Michif |

1,170 |

Saskatchewan (41.9%), Manitoba (17.5%) |

Haida |

445 |

British Columbia (98.9%) |

Tlingit |

255 |

Yukon (76.5%), British Columbia (21.6%) |

Kutenai |

170 |

British Columbia (100.0%) |

Total Indigenous language speakers |

260,550 |

Quebec (19.3%), Manitoba (15.5%), Saskatchewan (14.5%), Alberta (13.8%), Ontario (12.7%) |

Note: “Indigenous identity” is an expression that includes individuals who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuit and/or those who are Registered or Treaty Indians (that is, registered under the Indian Act of Canada), and/or those who have membership in a First Nation or Indian band.

Source: Statistics Canada, The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, 25 October 2017

According to Statistics Canada data, 92.6% of Indigenous language speakers in Canada speak a language from one of the top three families shown in Table 1: Algonquian, Inuit and Athabaskan languages. The most common Algonquian languages are Cree,[14] Ojibway (Anishinaabemowin) and Oji-Cree, with 96,575, 28,130 and 15,585 reported speakers respectively. For the Inuit languages, Inuktitut is the language most spoken with 39,770 reported speakers. Finally, Dene is the most common language for speakers of Athabaskan languages, with 13,005 reported speakers.[15]

Some Indigenous languages have official language status in the territories. In Nunavut, Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun are official languages, in addition to English and French.[16] The Northwest Territories recognizes 11 official languages:

- five Athabaskan languages (Chipewyan, Gwich’in, North Slavey, South Slavey and Tłı̨chǫ);

- one Algonquian language (Cree);

- three Inuit languages (Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut and Inuvialuktun); and

- English and French.[17]

Although only English and French are recognized as official languages in the Yukon, the Languages Act states that the territory “recognizes the significance of aboriginal languages in the Yukon and wishes to take appropriate measures to preserve, develop, and enhance those languages in the Yukon.”[18]

C. Indigenous electors

1. Participation By Indigenous Electors in the Electoral Process

Indigenous electors are among the groups of electors identified by Elections Canada as facing significant barriers to voting in federal elections. Known barriers include language barriers, remoteness and low population density, which make it difficult to recruit election workers and find polling places.[19]

Elections Canada points out that each group of Indigenous electors has its own unique history with federal elections. For example, the Métis had the right to vote in federal elections long before First Nations people living on reserve and Inuit. This history of Indigenous disenfranchisement in Canada is believed to be one of the reasons why Indigenous electors tend to vote in smaller numbers than non-Indigenous electors do.[20]

Elections Canada reports that, in the 43rd federal general election, turnout was lower for Indigenous electors living off-reserve compared with non-Indigenous electors (66.4% vs. 77.5%), and much lower among Indigenous electors who live on-reserve (51.8% vs. 67% of the general population). In addition, Indigenous electors were more likely to report not voting due to reasons related to the electoral process (21% vs. 12% of non-Indigenous electors).[21]

Results from the National Electors Study on the 43rd Canadian Federal General Election indicate that Indigenous electors were less likely to view voting as a duty compared to a choice (61% vs. 74% of non-Indigenous electors), and were less likely to be very satisfied with the service received from Elections Canada (59% vs. 67% of non-Indigenous electors).[22]

2. Elections Canada’s Current Initiatives Regarding Indigenous Languages

The Guide to the Federal Election,[23] distributed across the country for the 44th federal general election, provides information on voting rights, registration, voting methods, identification and voting assistance services. In its Report on the 44th General Election of September 20, 2021,[24] Elections Canada reported that 15,806,012 bilingual brochures were distributed across the country, as well as 10,159 trilingual brochures in Nunavut. As well, the guide is available on the Elections Canada website in 49 languages, including 16 Indigenous languages. The Voter ID Information Sheet[25] is also available online in these same Indigenous languages:

- Algonquian languages: Atikamekw, Moose Cree, Plains Cree, Innu (Montagnais), Mi’kmaq, Oji Cree, Ojibwe, Blackfoot, Saulteaux;

- Inuit languages: Inuktitut;

- Athabaskan languages: Dene, Gwich’in;

- Iroquoian languages: Mohawk;

- Tsimshian languages: Nisga’a;

- Siouan languages: Stoney; and

- Michif.

In Nunavut, information on the voting process was made available in Inuktitut, as were other materials such as the list of candidates, recruitment messages and training materials for election workers. A new feature of the 44th election, a facsimile (a poster replicating the ballot in Inuktitut to help electors mark their ballot) was placed in polling places.

Elections Canada states on its website that electors with questions about the electoral process can call the Elections Canada call centre or their local returning office and request information in the language of their choice. Over 100 languages are available by telephone, including some Indigenous languages. Immediate telephone interpretation is available upon request, subject to availability, and is not available at polling stations.

In addition, Elections Canada’s Indigenous Elder and Youth Program offers interpretation services, helps explain the voting process and answers questions from Indigenous electors. Elections Canada’s website states that this service is offered at any polling station that “serves mainly Indigenous electors” and that the agency has expanded its efforts since 2019 to increase participation in this program.[26]

D. Federal ballots

1. Ballot types and features

For federal general elections, there are two types of ballots: regular ballots and special ballots. Regular ballots, which are used on advance polling days and on polling day, are printed with the candidates’ names.

However, special ballots, used on days other than advance polling days and polling day, are blank, requiring electors to write in the name of their chosen candidate themselves. Special ballot voting kits include a ballot, an unmarked inner envelope, and an outer envelope that identifies the elector and their electoral district and contains a declaration that must be signed by the elector.[27]

The design and content of ballots are prescribed by the Canada Elections Act (CEA). The front and version of regular ballots are printed in accordance with Form 3 of Schedule 1 of the CEA, while special ballots are printed in accordance with Form 4 of Schedule 1 of the CEA.[28]

The CEA requires the use of the Latin alphabet on the ballot and the alphabetical ordering of candidates’ names. The CEA also sets out the physical features, such as a counterfoil and a stub, with lines of perforations separating them. These legislated physical features mean that current ballots can be printed only by a limited number of suppliers, especially given the tight time frame of federal elections.[29]

Currently, candidates’ names can appear in any language using the Latin alphabet. Candidates must provide proof of identification when they are nominated, and the name on that document is used on the ballot.[30]

For political parties, the party name appears on the ballot in the language the party chooses, and there is no requirement for a party to have a bilingual name. Currently, three federal parties have a French-only name, and one has an English-only name. Unilingual party names are not translated on the ballot.[31]

2. Ballot production timeline

The CEA requires that ballots be printed and distributed between the close of nominations (21 days before election day) and the first day of advance polls (10 days before election day). According to the Chief Electoral Officer, getting ballots printed and distributed in time across large and remote ridings is already a significant challenge.[32]

Table 2 shows the current ballot production process, as described in a letter from the Chief Electoral Officer to the Chair of the Committee dated 11 April 2022.[33] The steps are described below, with Day 0 corresponding to election day.

Table 2 – Ballot Production Timeline

Days |

Step |

Description |

Days 34/33-21 |

Nomination period |

Candidate nominations are open, and candidates may submit their nomination forms, including their name as it should be printed on the ballot. Nominations close on Day 21 at 2:00pm, with a deadline for withdrawals of 5:00pm local time. The ballot production process cannot start before this occurs as the list of candidates is not yet finalized |

Days 30-29 |

Ballot paper shipped to printing companies |

Elections Canada (EC) liaises with printing companies to confirm logistical details. Any printers no longer available are replaced. Printing companies are spread throughout Canada to reduce shipping delays. EC then ships the ballot paper to the printing companies and confirms receipt by Day 24. |

Days 21-18 |

Preparation of Ballot images |

Elections Canada headquarters (ECHQ) staff perform the following steps in preparing ballot images:

There are approximately 20 EDs, covering the northern half of Canada, where the timely distribution of ballot booklets to remote polling stations is a challenge. These EDs are treated as a priority and steps (a) to (e) are completed by the evening of Day 21 (presuming RO verification of all nominations is done by that time). The remaining EDs are processed in batches and completed no later than 7:00am on Day 18. If the RO identifies an issue with the information on the Verification Report or the ECHQ quality control inspection turns up a problem, the data for that ED must be corrected and the process restarted, with a new Verification Report and ballot PDF image. |

Day 21 (2 pm) |

End of nomination process |

Elections Canada headquarters (ECHQ) staff perform the following steps in preparing ballot images:

There are approximately 20 EDs, covering the northern half of Canada, where the timely distribution of ballot booklets to remote polling stations is a challenge. These EDs are treated as a priority and steps (a) to (e) are completed by the evening of Day 21 (presuming RO verification of all nominations is done by that time). The remaining EDs are processed in batches and completed no later than 7:00am on Day 18. If the RO identifies an issue with the information on the Verification Report or the ECHQ quality control inspection turns up a problem, the data for that ED must be corrected and the process restarted, with a new Verification Report and ballot PDF image.and the process restarted, with a new Verification Report and ballot PDF image. |

Day 19 (2 pm) |

End of the nomination approval process by Returning Officer (RO) |

Elections Canada headquarters (ECHQ) staff perform the following steps in preparing ballot images:

There are approximately 20 EDs, covering the northern half of Canada, where the timely distribution of ballot booklets to remote polling stations is a challenge. These EDs are treated as a priority and steps (a) to (e) are completed by the evening of Day 21 (presuming RO verification of all nominations is done by that time). The remaining EDs are processed in batches and completed no later than 7:00am on Day 18. If the RO identifies an issue with the information on the Verification Report or the ECHQ quality control inspection turns up a problem, the data for that ED must be corrected and the process restarted, with a new Verification Report and ballot PDF image. |

Days 21-18 |

Preparation and verification of ballot images. |

Elections Canada headquarters (ECHQ) staff perform the following steps in preparing ballot images:

There are approximately 20 EDs, covering the northern half of Canada, where the timely distribution of ballot booklets to remote polling stations is a challenge. These EDs are treated as a priority and steps (a) to (e) are completed by the evening of Day 21 (presuming RO verification of all nominations is done by that time). The remaining EDs are processed in batches and completed no later than 7:00am on Day 18. If the RO identifies an issue with the information on the Verification Report or the ECHQ quality control inspection turns up a problem, the data for that ED must be corrected and the process restarted, with a new Verification Report and ballot PDF image. |

Day 18 |

Ballot proof preparation |

The printing company prepares a ballot proof for the RO to inspect and approve, prior to the start of printing. The RO inspects the proof using a checklist and authorizes the start of printing. If the RO discovers a problem, this step must be repeated. |

Days 18-13 |

Production of the ballot booklets |

The printing company prepares the ballot booklets for the advance polls. This includes these high-level steps:

Printing companies have indicated that the perforating, cutting, and often serial numbers steps use separate specialized machinery operated manually with a slower production rate than printing. Many printing companies do not have this equipment, which limits options for ballot production. |

Days 14-13 |

Delivery of first booklets to ROs |

The printing company delivers the ballot booklets for the advance polls to the RO. |

Days 13 -11 |

Quality control of booklets and preparation for advance polls |

The RO and their office staff perform the following tasks:

|

Days 11-7 |

Advance polls |

During this period, quality control, such as making sure number of booklets received and serial numbers match the Record of Ballots, is done by election offices (EOs) and then ballots are issued at the polls. Once issued, DROs perform quality control as they use each booklet. If the CPS contingency supply is not used during advance polls, these are returned to the office on Day 7/6 for use at ordinary polls. Each book is “checked back in” to the RO office. |

Days 13-6 |

Preparation and delivery of election day booklets to RO |

After the printing company has completed printing the ballots for the advance polls, they continue to print ballots for the ordinary polls, repeating the steps performed on Days 18-13 above, and deliver the ballot booklets for the ordinary polls to the RO. |

Days 6-1 |

Quality control of booklets and preparation for ordinary polls |

The RO and their office staff repeat the tasks performed on Days 13-11, for the ordinary polls. |

Day 0 |

Ordinary polling day |

The CPS and DRO collect ballots, perform quality control, issue ballots as needed and track their usage. |

Source: Chief Electoral Officer, Letter to the Chair of the Committee, 11 April 2022, Annex 2.

Evidence and Briefs

A. Testimony of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada

The Committee began its study by hearing from the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, Stéphane Perrault, and other officials from Elections Canada.

Mr. Perrault said that he understood the importance for Indigenous people of having Indigenous languages on the ballot and that he was committed to increasing the use of Indigenous languages in the electoral process. However, Mr. Perrault urged the Committee to carefully consider the complexities and issues around the use of multilingual ballots.[34]

Mr. Perrault told the Committee that improving Indigenous language services is an important aspect of offering a more inclusive electoral process and reducing barriers for Indigenous voters. He also said that, more fundamentally, improving these services is part of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.[35] Furthermore, while he believes that Elections Canada has a limited impact on revitalizing these languages, he said that, symbolically, using Indigenous languages in the political and electoral processes is important.[36]

1. Options for amending regular ballots

As to the possibility of adding Indigenous languages to regular ballots, Mr. Perrault proposed four options. Each option raises specific policy, operational and electoral integrity concerns.

The first three options would require legislative changes, while the fourth could be implemented under the existing legal framework.[37] In general, Mr. Perrault supports the fourth option, as he does not recommend legislative changes at this stage.[38]

A table prepared by Elections Canada evaluating the policy considerations for each option is presented in Appendix A. Appendix B sets out the CEA provisions Elections Canada identified as requiring amendments to include Indigenous languages on ballots.

a) Option A: Mandatory multilingual ballot

The first option would be to offer voters an official multilingual ballot that includes one or more Indigenous languages in designated constituencies. Mr. Perrault noted that this option raises an important question about what threshold of an Indigenous population in a constituency would be required before including an Indigenous language on a ballot. Another question is whether there should be a maximum limit on the number of languages that can be included on a single ballot.[39]

Commenting on a potential threshold of Indigenous voters representing 1% of a constituency’s population, Mr. Perrault said that such a threshold would mean administering ballots in 17 languages in 27 constituencies, with up to five Indigenous languages on a single ballot in some constituencies.[40] Mr. Perrault said that defining a threshold must take into account demand and the capacity to offer translation or transliteration[41] on the ground.[42]

He added that having more than two languages on a single ballot, raises important questions about accessibility and design. For example, putting the names of parties and candidates in multiple languages on a ballot risks making a crowded, busy text that may be difficult to understand for some voters, including those with low literacy levels, an intellectual disability or a visual impairment. Mr. Perrault said that it would be critical to test the ballot design with user communities prior to incorporating this option into the CEA.[43]

In addition, Mr. Perrault said that Elections Canada were not experts on Indigenous languages, and that a ballot in a language other than English or French would require the transliteration of candidate names and the translation of party names. Elections Canada provides information products in 16 Indigenous languages. However, they have found that there are very few verification experts and translation timelines are sometimes substantial. Mr. Perrault noted that, if ballots were to be translated, it would significantly affect production timelines and the whole electoral calendar, which would likely need to be extended.[44]

Mr. Perrault also noted that multilingual jurisdictions typically use other solutions to provide ballots in the voter’s preferred language, including the use of electronic voting machines that allow voters to choose the language of the ballot and the interface. Sometimes, logos or symbols are used to replace party names.[45] Mr. Perrault also noted that all paper models have inherent limitations, as too many languages on a paper ballot can be confusing to voters.[46]

b) Option B: Multilingual ballot at the discretion of candidates and parties

The second option is a variation on option A, where an official multilingual ballot would be provided to voters. In this case, however, the CEA would be amended to permit candidates and parties to indicate how and in what languages their name should appear on the ballot. Parties would also indicate in which ridings their name would appear on the ballot in an Indigenous language.[47]

Mr. Perrault said that this approach is similar to that used in territorial elections in Nunavut, where candidates can put their names on the ballot in both the Inuit language and the Latin alphabet. Giving federal parties the choice of providing Indigenous versions of their name would also be consistent with the current approach, where parties can but are not required to have their names in both official languages.[48]

Although this option would remove the need for independent translation or transliteration of ballots, it raises other issues. For example, candidates must currently provide documentary evidence of their name. This raises the question of whether this requirement should be kept for Indigenous names as well as English and French names. If it were kept, questions arise as to whether Elections Canada would have to validate the transliteration, and who would determine which version of a party’s name is used in which riding.[49]

Finally, Mr. Perrault noted that under this model Indigenous voters would not be offered a ballot entirely in their own language. For example, some candidate or party names might be transliterated or translated, while others might not.[50]

c) Option C: Separate Indigenous language ballot

The third option presented by Mr. Perrault would be to amend the CEA to allow for a separate Indigenous language ballot at a voter’s request. Mr. Perrault said that this option would reduce the complexity of the ballots compared with the first two options, but would pose significant challenges with regard to production and distribution timelines.[51]

In addition, this option could compromise the secrecy of the vote in ridings with a small Indigenous language community. For example, having a separate ballot used by a limited number of voters could identify their voting choices.[52]

Mr. Perrault told the Committee that he does not recommend separate ballots.[53]

d) Option D: Facsimile (poster or replica) of the ballot in an Indigenous language

The fourth option presented by Mr. Perrault, and his preferred option, would be for Elections Canada to provide a facsimile of the ballot to be printed and then posted at the polling station or voting booth. The facsimile would reproduce the official ballot in one or more Indigenous languages and serve as a reference for voters.[54]

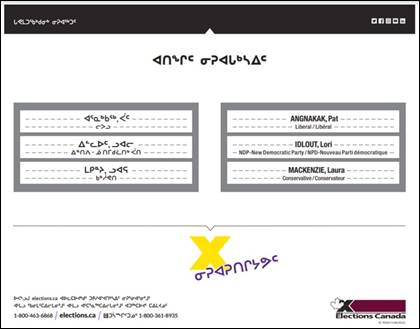

In the 44th federal general election, Elections Canada experimented with this type of ballot in Nunavut polling stations. Reproductions of the ballot in Inuktitut were displayed near the voting booths. Mr. Perrault said that, despite some production challenges, the facsimile was produced in time for the advance polls.[55] An example of a ballot facsimile poster displayed at polling stations in Nunavut is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Example of a Ballot Facsimile Poster Displayed at Polling Stations in Nunavut

Source: Elections Canada, Report on the 44th General Election of September 20, 2021, 27 January 2022.

According to Mr. Perrault, the experience in Nunavut did not result in much feedback, but no complaints were received about the ballot facsimiles. He suggested that perhaps no comments were received because people in Nunavut expect to see Inuktitut in documents. However, some complaints were received about other matters, including a “Vote Here” poster that was not translated into Inuktitut.[56]

Mr. Perrault said he would like to test this approach in other ridings using other languages in consultation with Indigenous communities. He also said that he wants to increase the availability of information products in Indigenous languages at the polls to reduce barriers faced by Indigenous voters and make their voting experience more reflective of their identity.[57]

According to Mr. Perrault, this approach would allow Elections Canada to become more familiar with Indigenous languages and more agile at using them outside of Nunavut. Testing facsimiles would involve working with candidates and parties, including transliteration of candidate names and, where appropriate, translation of party names. Timelines for the printing and production process could also be tested.[58]

2. Special ballots

Special ballots raise particular difficulties since voters must write out the name of the selected candidate. Under the CEA, languages other than those using the Latin alphabet are not accepted. The name of the candidate has to be written on the special ballot as it appears on the nomination paper.[59] As with regular ballots, any changes to the language used on special ballots would require a legislative amendment.[60]

Mr. Perrault said that, if special ballots in Indigenous language were used, it would create difficulties compiling the results of mail-in ballots that are sent to Ottawa in a national vote. For example, if voters were to write in the name of the candidate in several different languages and alphabets, the counting process would be more difficult. Mr. Perrault therefore invited the Committee to consider whether the addition of Indigenous languages should apply to special ballots, or only to regular ballots. He also noted that, in the Nunavut facsimile trial, only the regular ballots were reproduced in Inuktitut.[61]

Mr. Perrault also said that, if special ballots were to be translated into multiple languages, it would be difficult to ensure that the right ballot went to the right person, especially for voters outside Canada. He said it is best to keep the ballot as simple as possible because of the diversity of voters using mail-in ballots.[62]

3. Access to translation services

Mr. Perrault told the Committee that the timeliness and accessibility of translation varies greatly depending on the Indigenous language and the region of the country. In Nunavut, translation into Inuktitut is usually available within 24 to 48 hours, and ballots could probably be printed in that language. Amendments to the CEA would be required, for example to provide for the addition of a language to the ballot, who would validate the translation, the alphabetical order in which the names would be listed, and whether all names would have to be translated.[63]

According to Mr. Perrault, and based on past experience in producing facsimiles, Elections Canada basically has a 24-hour window to produce, print and distribute ballots in time for advance polls. This time frame does not allow time to validate the accuracy of the translation at that point in time.[64]

Mr. Perrault believes it is risky to use new languages on an official ballot until Elections Canada is certain of its ability to obtain a timely and accurate translation. He reported that Elections Canada usually uses the Translation Bureau for its Indigenous language needs.[65]

B. Evidence from representatives from other electoral agencies

The Committee heard from officials from electoral agencies where the use of Indigenous languages in the electoral process is enshrined. The Committee heard from Stephen Dunbar, Chief Electoral Officer of the Northwest Territories; Dustin Fredlund, Chief Electoral Officer of Nunavut; and Samantha Mack, Language Assistance Compliance Manager with the Alaska Division of Elections.

In their appearance before the Committee, both Mr. Dunbar and Mr. Fredlund acknowledged the importance of a candidate with an Indigenous name being able to see that name reflected on the ballot, even if that name is written in an alphabet other than Latin. Mr. Dunbar said that in some cases the anglicized version of an Indigenous name loses its meaning, and that including an anglicized name on a ballot could be offensive.[66] Mr. Fredlund brought up the impact of “Project Surname” in Nunavut in the 1970s, when the federal government began giving anglicized surnames to Inuit. Many individuals do not recognize those surnames as their own.[67]

Finally, they both said that they were always in discussions with Elections Canada and would be willing to work with or share their translated material with the federal agency.[68]

1. Northwest Territories

Mr. Dunbar told the Committee that there are 11 official languages in the Northwest Territories, and that the ability of residents to sustain a conversation in an Indigenous language ranges from less than two hundred for Inuktitut to more than 2,200 for Tł̨ıchǫ. He commented that while these numbers might appear low, it is important to note that most residents of the territory's smaller communities speak an Indigenous language[69].

The Northwest Territories Elections and Plebiscites Act currently only allows for the candidate's name and picture to be on the ballot, as there are no political parties represented in the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly. Mr. Dunbar told the Committee that the use of candidates’ photos ensures that electors who do not have full literacy are able to identify the candidate by sight.[70]

Mr. Dubar told the Committee that the territory's legislation requires candidates to state on their nomination form the name by which they are known in their community. Candidates do not have to submit government-issued documents to confirm their name. The ballot reflects the name on the nomination paper and are not translated.[71] The duration of an election in the Northwest Territories is 29 days long, and candidates have until the 25th day before election day to get their nomination papers in.[72]

There is no text to be translated on elections ballots, as these contain only names and photos. However, plebiscites are different, as the question posed in the plebiscite would be translated into the language that is commonly spoken in a given electoral district[73]. Mr. Dunbar provided as an example the 1992 plebiscite on the boundary between Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, where the question was translated into 10 of the 11 official languages. Translation in Cree could not be provided before the plebiscite occurred. The proclamation and instructions for voters were also translated in 10 languages. Depending on what languages were commonly spoken in the electoral district, the ballot could have up to four languages included on it.[74]

Mr. Dunbar informed the Committee that his office does face some difficulties in producing materials in all official languages. For example, the language bureau that provided translation in the context of the 1992 plebiscite no longer exists, and there is currently no “one-stop shop” for material to be produced in the 11 official languages. Elections Northwest Territories now relies on individual contractors who may not be able to produce materials in a timely fashion and may vary significantly in the speed of their work. Further, in some cases, considerable variation in terminology between dialects of the same language exists[75]. Mr. Dunbar indicted that providing material in different dialects is an ongoing discussion, and that for some regions of the Northwest Territories there will be more uniform translation and for others, materials might be community-specific.[76]

Elections Northwest Territories is currently in the process of ensuring that electronic voting information is published in the indigenous languages spoken in each electoral district. In polling places, Elections Northwest Territories is producing signs in various languages, including signs stating, “vote here” and “polling place,” as well as poster informing electors about ID requirements. The office is starting work on the material that will be necessary for the 2023 territorial general election.[77]

Another step taken by Elections Northwest Territories with regards to indigenous languages is for returning officers in each electoral district to arrange, when needed, for an interpreter to be available at each polling place. However, in communities where multiple languages are spoken, it is not always possible to have an interpreter available for each language.[78]

Mr. Dunbar also stressed that care must be taken to ensure that proper orthographic tools are installed on computers to support indigenous fonts. He noted that the default settings in word processors can present Indigenous fonts using incorrect diacritical marks.[79]

2. Nunavut

Mr. Fredlund told the Committee that the Nunavut ballot includes candidate names in any of Nunavut’s official languages. Inuktitut is written in syllabics, while Inuinnaqtun is written in the Roman alphabet.[80] The duration of an election in Nunavut is 35 days, and candidates must submit their nomination papers between 35 and 30 days prior to the election.[81]

Elections Nunavut relies on candidates for the spelling and transliteration of their names. The names are provided during the declaration period and included on the ballot. Mr. Fredlund explained that Elections Nunavut does have in-house capacity to ensure each name that is written in Inuktitut syllabics accurately depicts the candidate’s choice, and to understand write-in ballots written in syllabics.[82] Further, Elections Nunavut is legally required to appoint poll workers who speak the language of the community.[83]

In 2019, Nunavut held their municipal election around the same time as the federal election, and therefore Elections Nunavut shared many venues with Elections Canada. Mr. Fredlund observed that while Elections Nunavut produced all materials in four languages, including ballots, that was not the case for Elections Canada documentation. He shared with Committee that some electors experienced confusion distinguishing between the two organizations, and as a result, Elections Nunavut received many complaints regarding products only provided in English and French during the election[84].

Mr. Fredlund also highlighted that there are different dialects within Inuktitut-speaking communities, but that Inuktitut speakers can generally understand each other enough that there is no need to provide documentation in 25 dialects.[85]

3. Alaska

Ms. Mack informed the Committee that Alaska is currently undergoing the implementation of a ranked-choice voting process. To inform electors of the change, her department has launched a vast educational campaign that's being carried out in nine Alaska-native languages in addition to Spanish, English and Iñupiat. She told the Committee that the inclusion of indigenous languages in the elections process does not end with the ballot, but also encompasses outreach advertising and public communications.

In the United States, pursuant to section 203 of the federal Voting Rights Act, a state or political subdivision must provide language assistance to voters if more than 5% of voters share a common language while speaking or understanding English less than very well.[86]

To translate indigenous languages, Alaska Division of Elections utilizes a panel model wherein multiple speakers of each indigenous language meet to translate together.[87] Ms. Mack told the Committee that dialectical differences is the most challenging aspect of translation work. As such, a panel translation model was implemented to bridge the divide between standardization and specificity. She noted that the translation panels have been instrumental in making sure that the material is understood across a wide geographic area.[88]

C. Evidence from the member for Nunavut

1. Nunavut: context of federal elections in the territory

Lori Idlout, the member for Nunavut, told the Committee that the Nunavut Act[89] provides the government of Nunavut with the authority over how elections work within the territory of Nunavut.[90] Further, she noted that article 32 of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement[91] addresses language and culture. She said that while this article does not contain specific wording about language or elections, it addresses social development and the provision of opportunities for Inuit to participate in that development.[92]

Ms. Idlout told the Committee that Nunavut’s population is 36,858, according to the 2021 census. Of these individuals, about 85% are Inuit who live in 25 communities.[93]

She said that the voter turnout in Nunavut for the 2021 federal election was about 34%.[94] She noted that while voter turnout for federal elections was high in Nunavut when Nunavut was first created, it has since declined and remained low. Ms. Idlout attributed the low voter turnout to “the attempt to separate language and culture” in the federal voting system, which she described as “another indication of the impacts of colonialism.”[95]

2. Barriers to voting in federal election for Nunavummiut

According to Ms. Idlout, the federal election workers serving voters at polling places in Nunavut greet voters in only English or French. Further, the federal ballot is written, as per the Canada Elections Act,[96] in only English or French, although she noted that Elections Canada ran a pilot project during the 2021 general election that provided voters with a sample ballot written in Inuktitut.[97]

According to Ms. Idlout, most elders in Nunavut cannot read English or French. To this end, she recounted having to describe to people that her name was the one in the middle of the ballot, between two other candidates. She stated this situation was unacceptable in a modern Canada, and that to make reconciliation meaningful, Indigenous languages needed to be protected and promoted.[98]

Further, Ms. Idlout noted that unilingual Inuktitut speakers find the complaints process inaccessible when seeking to report the barriers they face to Elections Canada, as complaints must be lodged in English or French.[99] She also noted that Nunavummiut today remained reluctant to lodge complaints because for generations they faced oppressive atrocities (e.g., were beaten with metre sticks, etc.) for speaking their language, and singing their songs.[100]

Ms. Idlout told the Committee that she heard of people had been turned away from voting in Nunavut because of language barriers. She stated that the difficulties Nunavummiut faced in order to exercise the basic right of voting was “such a sad story in Canada.”[101]

Ms. Idlout recounted to the Committee of having heard many people in Nunavut say that they do not vote because “it’s not going to make any difference.” She believes that “many First Nations, Métis, and Inuit have lost the sense of using their voice because their voice doesn't matter.”[102] She stated that Parliament needed to work harder to ensure that these voices were heard.

3. Proposed Solutions

Ms. Idlout told the Committee that she had five recommendations to make concerning this study. These were:

- That Elections Canada learn from Elections Nunavut about running elections in four languages;

- That Elections Canada hire full-time Indigenous interpreter-translators to help build the necessary expertise and corporate knowledge for future federal elections;

- That the current complaints process at Elections Canada be improved for unilingual Indigenous people to voice their concerns;

- That a study be conducted on Indigenous governance within Canada's democracy as another form of reconciliation; and

- That that the federal government respect Indigenous cultures to build the trust that is necessary for real reconciliation.[103]

In addition, Ms. Idlout also noted that, in her view, Indigenous languages should appear on federal election ballots throughout Canada.[104] She indicated that in order to do this, in her view, the extent of Indigenous language loss by community needed to be ascertained, and those communities with language losses ought to be provided with ballots in their Indigenous language.[105] Further, Ms. Idlout stated that ensuring the provision of Indigenous ballots was insufficient and that services at polling places needed to be in the appropriate Indigenous language(s).[106]

Further, Ms. Idlout noted that Elections Canada must ensure election workers in Indigenous communities receive trauma-informed training. She held concerns that election workers who have not received training to deal with people who have suffered trauma will appear “very colonial.”[107]

Lastly, Ms. Idlout stated that parliamentarians needed to do a better job of informing constituents, including Indigenous communities, about the federal services that are available to them.

D. Evidence from representatives from Indigenous groups or agencies

1. Representatives from Nunavut

i. Context of federal lections in Nunavut

Ms. Kotierk told the Committee that the territorial Inuit Language Protection Act[108] (IPLA) applied to federal agencies, departments and institutions.[109] In her view, section 3 of the ILPA requires Elections Canada to use the Inuit language to display public signs, display and issue posters, and provide reception services in client or customer services that are made available to the public.[110] She told the Committee that Elections Canada had failed to implement its Inuit-language obligations and comply with the ILPA in Nunavut.

Ms. Aariak indicated to the Committee that, in her view, Canada should focus on articles 5 and 13 when implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).[111] She stated that article 5 sets out that Indigenous peoples have the right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic, social, and cultural life of the state. Article 13 required subscribing states to take effective measures to ensure that Indigenous language rights were protected and that Indigenous peoples can understand and be understood in political, legal, and administrative proceedings.[112] Ms. Kotierk indicated that ensuring that the Inuit language was on the federal ballot would be a step taken in the right direction by Canada in its commitment to implement UNDRIP.

Further, Ms. Kotierk provided the Committee with historical information about voting rights for the Inuit. She stated that the Inuit once lived nomadic lives and governed themselves with very limited government interaction until around the 1940s to 1960s.[113] At this time, the Inuit were moved by the government into communities. While the Inuit were given the right to vote in 1950, it was not until 1962 that the Inuit communities had access to voting services.

Ms. Kotierk stated that the voter turnout in Nunavut for the 2019 federal election was 48%. She contrasted this with the overall voter turnout of 67% and indicated that Nunavut had the lowest turnout of all provinces and territories.[114]

ii. Barriers to voting in federal election for Nunavummiut

Ms. Aariak told the Committee that Nunavut has three official languages: Inuktut, which includes Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun; English; and French.[115] Ms. Kotierk stated that the 2016 census showed that in Nunavut, there were 11,020 English-speakers, 595 French-speakers, and 22,600 Inuit language-speakers.[116] As such, Nunavut Inuit expect to hear, see, read and speak Inuktut in all aspects of their daily lives in Nunavut. This expectation included being able to cast a ballot in Inuktut.

Ms. Aariak provided the Committee with a series of examples in which electoral information was provided to voters in Nunavut in English and French only. These included posters, dates and hours of operation for advance polls, information regarding special ballots, and the writing of the name of Elections Canada itself.[117]

Ms. Aariak stated that the election ballots used in municipal and territorial elections across Nunavut included Inuktut. She believed that Elections Canada should not adhere to a lesser standard.[118] Indeed, Ms. Kotierk noted that for municipal and territorial elections in Nunavut, services, materials, and supports for candidates and electors were made available in Inuktut. Candidates are also afforded the opportunity approve the syllabics for their name that will appear on the ballot. She noted that she was unaware of any difficulties in procuring translation or printing services for Inuktut in Nunavut.[119]

Ms. Kotierk recounted hearing of an Iqaluit resident employed as a federal election worker who was asked by Elections Canada to translate a sign that stated, “mandatory mask.” This person commented that translation was not part of her job and found the lack of signage in Inuktut to be disheartening.[120]

Ms. Kotierk commented that she found it commendable that Elections Canada had translated the voting guide, voter information cards and some other material into Inuktitut, and that Elections Canada’s information campaign included advertisements in Inuktitut. However, she noted that Inuktut was not on the ballot, and that she found the efforts by Elections Canada to be inconsistent, ad hoc and dependent on the goodwill of the staff of the day.[121]

iii. Proposed solutions

Ms. Aariak told the Committee that federal agencies, departments and institutions, including Elections Canada, needed to commit to taking all necessary steps for the usage, preservation, revitalization and promotion of the Inuit language in Nunavut.[122]

She provided the Committee with three recommendations. These were:

- That the CEA be amended to include both Roman orthography and Inuktitut syllabics on federal election ballots;

- That the CEA use Inuit-language text in Elections Canada public signs and posters that are at least as prominent as English and French; and

- That a policy be created and implemented to ensure Elections Canada complies with its obligations as set out in the IPLA.[123]

For her part, Ms. Kotierk supported including Indigenous languages on ballots in ridings with a “substantial presence” of Indigenous peoples. In addition, she supported allowing electors to request special ballots in the indigenous language of their choice no matter where they lived.[124]

Ms. Aariak told the Committee that in Nunavut, there were many Inuit language resources and a language authority that Elections Canada could make use of.[125]

2. First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Youth Network

i. Priorities of the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Youth Network

Shikuan Vollant, Spokesperson for the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Youth Network told the Committee that he supported all initiatives that enhanced or revitalized Indigenous languages. However, he stated that the inclusion of Indigenous languages on federal election ballot was not a priority for the people in his community. He stated that if the goal of this initiative was to revitalize Indigenous languages, he would far rather that the funding for the initiative be instead used to recognize and financially compensate Indigenous elders, build gathering spaces where Indigenous languages were taught, or organize trips with young Indigenous community members.[126]

Cédric Gray-Lehoux agreed and stated that, in his view, the money that would be better used should it be spent on creating places for connecting Indigenous people with the land and their elders, and helping to maintain the cultural connections that have been systematically destroyed for hundreds of years by various institutions.[127]

Mr. Gray-Lehoux indicated that priority needed to be given to creating systems for learning Indigenous languages and that the focus first ought to be on reconnecting young Indigenous people and with their language and their culture.[128] To that end, Mr. Vollant stated that he was 30 years old and part of one of the last remaining generations who can speak the Innu language perfectly. In his view, priority must be given to promoting Indigenous languages among young people. He stated that many of his nephews and nieces currently speak more English, because of the Internet and social media, than they do Innu.[129]

Mr. Vollant told the Committee that, in his view, so long as the Indian Act[130] continued to exist, Indigenous people were not going to feel at home in the House of Commons.[131]

ii. Concerns about including Indigenous languages on ballots

Mr. Vollant told the Committee that voter turnout among Indigenous people during federal elections was about 40%. He stated that there were many reasons for this, but that no study had mentioned ballot translation as a solution to this abstention.[132]

Mr. Vollant and Mr. Gray-Lehoux held several concerns about the initiative to include Indigenous languages on federal election ballots. These included:

- That this initiative would “cost an enormous amount of money” that could be better spent on programs and facilities to revitalize Indigenous language and culture.[133]

- That translating ballots into the 60 First Nations, Métis and Inuit languages would inevitably add to the waste generated by elections and his organization denounced this potential environmental impact.[134]

- That it would add a level of complexity to voting. For example, in Quebec there are 11 different Indigenous languages. However, these Indigenous peoples were relatively nomadic, often moving for reasons of work or school. As such, 11 Indigenous languages would conceivably need to be represented in every polling station in Quebec. In practical terms, this was too heavy a burden for electors and for election workers.[135]

- That the correct pronunciation and correct written form used in each of the 43 First Nations communities in Quebec and Labrador would create a linguistic and logistical nightmare.[136]

Further, Mr. Vollant noted that the word “vote” does not currently exist in the Innu language. He told the Committee that it would likely be easier for a young Indigenous person from his community to read the word vote in French rather than invent a new word, that would likely be quite long, that they have never heard or read before.[137]

Mr. Vollant stated that in his community, he learned to speak Innu before he learned to read or write it. As such, he indicated that he, as a very proficient speaker of Innu, can struggle to read many words in Innu.[138]

Mr. Vollant told the Committee that his mother barely can speak French; however, she votes in federal elections in French. As such, he stated that having ballots in Innu, in addition to French, would not do anything for his community.[139]

Lastly, Mr. Vollant and Gray-Lehoux indicated that the initiative to have Indigenous languages on federal ballots was well-intentioned but they did not believe that it was a priority.[140] They recognized that peoples of Nunavut have a different experience in that their language was relatively homogenous within their territory. However, within Quebec and Labrador, there are 11 nations with 11 distinct languages.[141]

3. Institut Tshakapesh

Ms. Tshernish told the Committee that many members in her community did not feel included in Canada’s democracy and have, as such, abstained from voting or participating in the Statistics Canada census. This abstention has had numerous important consequences for Indigenous communities.[142]

Ms. Tshernish stated that providing documents, including ballots, and services at federal elections in Indigenous languages would help to allow Indigenous people to be fully included as citizens. It would grant First Nations the right to express themselves, while recognizing their nation, language, culture and identity.[143]

She stated that she was in favour of including Indigenous languages on federal election ballots as it was time to go beyond making symbolic gestures to Indigenous peoples and instead put in place concrete actions.[144] She indicated that inclusion was very important to her community, along with consultation and mutual respect for each other’s ways of life.[145]

Ms. Tshernish noted that for the Innu in constituencies of the Côte-Nord, three dialects were used. However, she indicated that the wording on federal election ballots could be written in only one dialect with some words written in three dialects.[146]

Ms. Tshernish suggested that Indigenous languages also be included on the voter information card, posters at polling places, and advertisements about voting.[147]

4. First Nations Education Council

i. Context of federal elections according to the First Nations Education Council

Denis Gros-Louis, Director General, First Nations Education Council, told the Committee that his educational association represented eight of the 11 Nations in Quebec.[148]

Mr. Gros-Louis indicated that, in his view, the initiative to include Indigenous languages on federal election ballots was a good first step in respecting Indigenous languages and would help to promote reconciliation and preservation of language.[149]

He stated that Indigenous languages serve as a vehicle for expressing their view of the world and are the cornerstone of Indigenous identity.[150]

Further, Mr. Gros-Louis stated that many Indigenous communities do not feel involved in federal issues. In his view, there are many reasons First Nations voters are disengaged, including the continued detrimental effects of the Indian Act, a lack of respect on the part of federal partners, and a feeling that federal issues are not challenging or of interest.[151]

Mr. Gros-Louis noted that a study conducted by Elections Canada on the voter turnout rate of First Nations electors shows that the communities in Quebec have a participation rate in federal elections of around 27.8%.[152] He told the Committee First Nations communities have differing viewpoints, if not polarized viewpoints, about participation in federal elections. Some participate while others categorically refuse to participate. He indicated that recent data from Statistics Canada show that the main reason that Indigenous people do not vote was political in nature.[153]

Mr. Gros-Louis did not agree with assertions that adding Indigenous languages to federal ballots was an expensive exercise. He stated that, in his view, repairing the damages caused to Indigenous languages and cultures does not have a price.[154]

ii. Proposed solutions

Mr. Gros-Louis told the Committee that he had four recommendations to make concerning this study. These were:

- That awareness training be provided at Elections Canada to senior management and staff. This training should focus on Indigenous history and enhancing cross-cultural aptitudes, in line with action number 57 from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

- That Elections Canada formally consult and collaborate with the Office of the Commissioner of Indigenous Languages, which is the watchdog of Indigenous languages in Canada.

- That Indigenous languages be included on federal ballots and that a document be developed by Elections Canada in collaboration with the Atikamekw Nation that provides information about the electoral process and the conduct of elections and that the other ten nations in Quebec be offered the same opportunity.

- That the images shown in election documents and booklets reflect the identity of Indigenous nations.[155]

Mr. Gros-Louis told the Committee that Elections Canada should collaborate with Indigenous communities, including those that he represents, to shore up their lack of expertise and capacity in Indigenous matters. He stated that Elections Canada should contact them right now, as being proactive was a gesture of reconciliation.[156]

Mr. Gros-Louis showed an Elections Canada document to the Committee that had been translated in collaboration with the Atikamekw nation. He indicated that he would table it with the Committee to be presented to Elections Canada.[157]

E. Academic perspectives

The Committee heard testimony from three witnesses from the academic community. In addition to Ms. Harell, these witnesses were Jean-François Daoust, Assistant Professor at the University of Edinburgh and Dwight Newman, Professor of Law at the University of Saskatchewan and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Rights in Constitutional and International Law.

These three witnesses spoke about the importance of consulting with the various Indigenous communities to understand their needs and expectations in relation to the electoral process. They also agreed that, for languages whose survival is threatened, multilingual ballots are not a priority and that it is more important to invest in other types of support.[158]

To that end, the Committee acknowledges that academic studies on the topic of Indigenous peoples and the federal electoral process are a constantly evolving subject-matter. At present, research into this field of knowledge has its limitations, a reality that academic researchers themselves acknowledge. The Committee agrees with the testimony by academic researchers that Indigenous engagement and collaboration in this field of research was important to gain a better understanding about the different barriers Indigenous communities face.

On the issue of adding candidate photographs to ballots, opinions were divided. Mr. Daoust felt that it would open the door to unfortunate consequences, as we know that even alphabetical order can have an unconscious effect on voters’ choices. Ms. Harell said that creative solutions should be sought, and that if photographs offer multilingual information, that option should be considered. However, she acknowledged that Mr. Daoust’s concerns are appropriate. Mr. Newman also sees the need to look for creative solutions, while considering the other problems that such an initiative could cause.[159]

1. Jean-François Daoust, Assistant Professor, University of Edinburgh

Mr. Daoust told the Committee that he sees three aspects to the issue of including Indigenous languages on ballots: a normative aspect, a technical aspect and an empirical aspect. Mr. Daoust’s presentation focused on the first and third aspects.[160]

With respect to the normative aspect, Mr. Daoust encouraged the Committee to think about the values of Canadian society and how they might be reflected in public policy and the electoral process. In his view, because Canadian society claims to be inclusive, this means promoting inclusion of all groups in society in the democratic process, especially groups who face systemic barriers and who participate less in democratic life. In that sense, it seems consistent and desirable to enable Indigenous people to vote by having access to ballots in their language. For that reason, he said that the Committee should have a positive view of this kind of initiative and its aim of inclusion.[161]

As to the empirical aspect, Mr. Daoust asked whether an increase in Indigenous voter turnout could be expected as a result of this measure. Based on his research, he said that it is unlikely that adding languages to the ballot would have a significant impact on participation. He suggested that such an initiative would only increase voter turnout if it made the voting process easier and if this consideration, the ease of voting, had a major influence on voters’ decision of whether or not to vote. In general, however, the vast majority of people find voting to be easy, which means that those who do not vote usually do so for reasons unrelated to how easy it is to vote,[162] whether they are Indigenous or not.[163] Mr. Daoust said that interest in politics and seeing voting as a duty rather than a choice are factors that have more impact on participation than ease of voting.[164]

Mr. Daoust concluded that he sees no normative reason not to include Indigenous languages on ballots, but that, based on the scientific literature, such a measure should not be expected to significantly increase Indigenous voter turnout. However, he said that his conclusions are based on relatively limited research data and on samples gathered from Indigenous people.[165]

Responding to a question asked by the Committee, Mr. Daoust mentioned that the symbolic aspect of such an initiative can sometimes be underestimated. Symbols can influence political attitudes, build trust in the federal government, and increase interest in politics. The indirect impact of the symbolic aspect of such a measure may be more substantial than the direct impact on turnout.[166]

2. Dwight Newman, Professor of Law at the University of Saskatchewan and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Rights in Constitutional and International Law

Mr. Newman reminded the Committee that, in 2021, Canada adopted the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDRIPA). Section 5 of UNDRIPA establishes a statutory requirement for the government to take all measures necessary to ensure that Canadian legislation is consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).[167]

Section 13(2) of the UNDRIP requires that states take effective measures to ensure indigenous peoples can understand and be understood in political, legal and administrative proceedings where necessary through the provision of interpretation or by other appropriate means.[168] Mr. Newman stated that, in his view, article 13(2) likely does not mandate any specific requirements concerning ballots being available in Indigenous languages, partly because it establishes rights for Indigenous people as collective entities rather than individuals. However, he stressed that the inclusion of Indigenous languages on ballots would be in accord with the underlying objectives of the UNDRIP.[169]

Further, Mr. Newman referred to provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protecting the right to vote and providing safeguards against discrimination. He noted that these provisions may offer the strongest legal arguments about removing impediments to voting, such as linguistic barriers, particularly in the case of individuals who use other languages and have limited proficiency in English and French. [170] However, he was unaware of any case law on this topic.[171]

Mr. Newman told the Committee that Canada is somewhat of a laggard on linguistic issues related to voting, notably when compared to the United States. As Ms. Mack also stated to the Committee, section 203 of the American Voting Rights Act established various forms of language assistance in districts where it is needed for minority language communities, Indigenous or not. This provision dates back to 1975 amendments to the Voting Rights Act. However, Mr. Newman mentioned that certain challenges arose when it came to implementing this statutory obligation in the US.[172]

Mr. Newman highlighted key questions for the Committee to consider, including:

- whether or not Nunavut is a special case, and if implementing a pilot program in Nunavut would be appropriate before expending the project to other ridings;

- whether there would be specific cut-offs in terms of proportions of the population able to vote in other languages;

- what particular form of Indigenous languages might be used on ballots, whether in the form of syllabics or in transliterated forms for languages that have both versions;

- what costs would be involved and whether those costs might be more optimally invested in other ways of supporting Indigenous electoral participation;

- whether the use of sample or facsimile ballots is a valid option;[173]

- how a crowded ballot would raise issues for access by persons with certain disabilities;[174] and

- whether other forms of language assistance should be implemented.[175]

Mr. Newman highlighted the importance of collaborating with Indigenous communities across the country to gain an understanding about the different barriers they face.[176] He told the Committee that he held the view that there should be strong protections for Indigenous language rights, but whether such protections ought to be identical to English and French raised certain questions, especially considering the great diversity of Indigenous languages in Canada.[177]

3. Allison Harell, Professor, Political Science Department, University of Quebec at Montreal

Ms. Harell raised three questions for the Committee to consider regarding the inclusion of Indigenous languages on federal election ballots.

First, she asked whether the absence of Indigenous languages constituted a barrier to political participation. Her studies have shown that socioeconomic resources are an important barrier to all electors, including for Indigenous people's participation in elections. However, other factors, such as trust in the federal government and the salience of Indigenous issues are also important, especially for young Indigenous electors.[178]

Ms. Harell stressed that the inclusion of indigenous languages on ballot would be an important symbolic gesture to show Canada’s interest in the participation of the Indigenous electors. Ms. Harell also noted that electoral participation remains a choice, and while it is important to remove barriers to participation, many Indigenous voters may choose to abstain from voting for other reasons.[179] She also pointed out that while some Indigenous individuals might not vote at federal elections, they may be politically active in other respects in their communities.[180]

Secondly, Ms. Harell recognized that the inclusion of a diversity of Indigenous languages on ballots presented challenges. These included the tight production timelines for ballots under the current legislative framework. However, there were also benefits to having multilingual ballots, such as removing an unfair barrier to participation. In her view, Indigenous languages on ballots could also constitute a step toward reconciliation. Ms. Harell also noted that there was a need to make a strong statement, as settlers, that Indigenous nations are on an equal footing with English and French in Canada[181].

Ms. Harrel concluded with her third point: the key issue for considering Indigenous languages on ballots should be whether Indigenous nations and electors want such a change in order to fully participate in the electoral process. Consultation is therefore very important, and she stated that building consultation capacity within Elections Canada would be a sensible step forward.[182] While there may be costs and challenges in implementing multilingual ballots, she indicated that reconciliation requires a serious commitment to make the electoral process accessible to Indigenous electors in their own language.[183]

Ms. Harell stated that implementing a pilot project would make sense, and that implementing a countrywide process that end up failing would have detrimental consequences on people’s trust in the electoral system.[184]

Discussion and Recommendations

A fundamental aspect of Canada’s electoral system is that all citizens eligible to participate in a federal general election should not encounter undue barriers when exercising their right to vote.

During this study, the Committee heard with great interest about the challenges created by language barriers that exist for Indigenous electors seeking to vote during federal elections, especially for unilingual Inuit living in Nunavut.

At the same time, the Committee also heard that considerable work remains to be carried out by Parliament and parliamentarians, when it comes to increasing Indigenous peoples’ engagement in the federal electoral system and process. Indeed, the Committee was troubled to hear of the widespread low voter turnout among Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The Committee takes seriously Canada’s commitments to Indigenous people about reconciliation. While improving the experience in voting at federal elections for Indigenous peoples may only be a small step in reconciliation, nonetheless it is a step in the right direction.

Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That a pilot project be undertaken by Elections Canada, in partnership with Elections Nunavut, to include Inuktut languages on federal election ballots in the federal electoral riding of Nunavut.

Recommendation 2

That an Indigenous communities advisory group be struck by Elections Canada to collaborate with Elections Canada to formulate recommendations about making the federal electoral process as accessible as possible for Indigenous voters.

Recommendation 3

That Elections Canada print and post facsimiles of the official ballot in Indigenous languages to serve as a guide for electors at the polling station and/or voting booth, where appropriate, as determined by the Indigenous communities advisory group.

Recommendation 4

That Elections Canada consult with the federal Commissioner of Indigenous Languages as a matter of guidance on these issues.

[1] House of Commons, Standing Orders of the House of Commons, Standing Order 108(3)a)(vi).

[2] Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs (PROC), Minutes of Proceedings, 14 December 2021.

[3] PROC, Minutes of Proceedings, 22 June 2021.

[4] PROC, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Meeting 16, 7 April 2022, 1210 (Marjolaine Tshernish, General Manager, Institut Tshakapesh).

[5] PROC, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Meeting 14, 31 March 2022, 1105 (Karliin Aariak, Commissioner Office of the Languages Commissioner of Nunavut).

[6] Ibid., 1110.

[8] PROC, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Meeting 14, 31 March 2022, 1115 (Aluki Kotierk, President Nunavut Tunngavik Inc.).

[10] PROC, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Meeting 16, 7 April 2022, 1115 (Allison Harell, Professor, Political Science Department, University of Quebec at Montreal).

[12] Note that certain institutions and reserves did not participate in the 2016 Census as enumeration was not permitted, or it was interrupted before completion.

[13] Statistics Canada, The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, 25 October 2017.

[14] Cree languages include the following categories: Cree not otherwise specified (those who responded “Cree”), Plains Cree, Woods Cree, Swampy Cree, Northern East Cree, Moose Cree and Southern East Cree.

[15] Statistics Canada, The Aboriginal languages of First Nations people, Métis and Inuit, 25 October 2017.

[16] Government of Nunavut, Official Languages.

[17] Government of the Northwest Territories, Languages Overview.

[18] Yukon, Languages Act, RSY 2002, c. 133.

[19] Elections Canada, Report on the 44th General Election of September 20, 2021, 27 January 2022.

[20] Elections Canada, Indigenous Electors.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Elections Canada, National Electors Study on the 43rd Canadian Federal General Election.

[23] Elections Canada, Guide to the federal election.

[24] Elections Canada, Report on the 44th General Election of September 20, 2021, 27 January 2022.

[25] Elections Canada, Voter Identification – Other Languages.

[26] Elections Canada, Information for Indigenous Electors.

[27] Elections Canada, “Chapter 9 – Ballots (08/2021)” and “Chapter 12 – Special Voting Rules (08/2021)” in the Returning Officer’s Manual (08/2021).

[28] Canada Elections Act, S.C. 2000, c. 9, sections 116(1), 138(1), 186 and Schedule 1.

[29] PROC, Evidence, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, Meeting 13, 29 March 2022, 1105 (Stéphane Perrault, Chief Electoral Officer, Elections Canada).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.; Chief Electoral Officer, Letter to the Chair of the Committee, 11 April 2022, Annex 2.

[33] Chief Electoral Officer, Letter to the Chair of the Committee, 11 April 2022, Annex 2.

[35] Ibid., 1105.

[36] Ibid., 1230.

[37] Ibid., 1105.

[38] Ibid., 1110.

[39] Ibid., 1105.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Transliteration can be defined as the “representation of a lexical item recorded in one writing system by means of the signs and symbols of another.” See the record on transliteration in Termium Plus.

[43] Ibid., 1105.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid., 1110.

[46] Ibid., 1130.

[47] Ibid., 1105.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid., 1110.