ENVI Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

The Government Of Canada’s Planned Phase-Out Of Fossil Fuel Subsidies And Of Public Financing Of The Fossil Fuel Sector

Introduction

On 3 February 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) adopted the following motion:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee conduct a study of the government’s commitments to accelerate Canada’s G20 commitment to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies from 2025 to 2023 and to develop a plan to phase out public financing of the fossil fuel sector, including by federal Crown corporations; that the study include a review of the definition of a subsidy and the criteria used to determine if a subsidy is inefficient, how those commitments contribute to achieving Canada’s climate targets and obligations under the Paris Agreement, and how Canada plans to meet those commitments; that experts and stakeholders be invited to appear; that the Minister of Environment and Climate Change and the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance be invited to appear; that the study consist of no fewer than five meetings; that the committee report its findings to the House of Commons; and that all meetings be televised.[1]

The Committee began its study on 29 March 2022 and heard from 37 witnesses from 27 organizations over five meetings. Members agreed to incorporate into the evidence the speaking notes of one witness who was unable to appear.[2] The Committee received 19 briefs.[3] The Committee sincerely thanks all witnesses and authors of briefs for their contributions to this study. The Committee wishes to note that the situation in relation to eliminating inefficient fossil fuel subsidies and developing a plan to phase out public financing has continued to evolve since the Committee last heard testimony on this topic on 5 May 2022, and that there may be government documentation more recent than that cited in the testimony.

Background and Context

As part of its efforts to achieve Canada’s climate change targets and obligations, the federal government has made several commitments to reduce its financial support to the fossil fuel industry.

This section begins by providing some brief background about the state of climate change and its impacts around the world and in Canada. It then offers an overview of the main global agreements related to climate change, and of Canada’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in this context, and the impact it would have on Canadians and Canadian industry.

Climate Change

Human-caused GHG emissions are estimated to have raised the earth’s average temperature to about 1.1°C above its pre-industrial average.[4]

The global mean temperature for 2021 was 1.11 ± 0.13 °C above the pre-industrial average, and the last seven years have been the warmest seven years on record.[5] The effects of this heating—water scarcity, heat waves, forest fires, extreme precipitation, sea-level rise, and species and ecosystem losses—are expected to worsen with every increment of warming.[6]

There is consensus among climate scientists that the increase in global average temperature by the end of the 21st century must be held near 1.5°C, and well below 2°C, above the pre-industrial average, to reduce the risks and impacts of climate change significantly.[7]

To limit global warming and its harmful impacts, it is necessary to limit the total cumulative global anthropogenic emissions of CO2 within a “carbon budget.”[8] For a 67% chance of keeping warming under 1.5°C, the remaining global carbon budget, which is the maximum amount of CO2 that can be emitted, is estimated to be approximately 400 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2.[9] Annual net global emissions of CO2 have been estimated at approximately 42 ± 3 Gt by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[10] To limit warming, it is also necessary to limit emissions of other GHGs,[11] which warm the Earth to different extents and stay different lengths of time in the atmosphere.[12]

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), annual global GHG emissions must be reduced steadily from current levels to about 25 Gt of CO2 equivalent by 2030 to yield a good chance of keeping the global temperature increase below 1.5°C by 2100.[13]

Another way to understand the changes to the climate is in the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere,[14] because CO2 is a significant GHG that is emitted during the burning of fossil fuels, as well during wildfires and volcanic eruptions. The level of atmospheric CO2 was measured at 419 parts per million (ppm) in July of 2022,[15] 50% higher than at the beginning of the industrial era, and significantly higher than it has been in hundreds of thousands of years.[16]

Climate change impacts are not felt evenly around the world, or by all members of affected communities. Among other outcomes, this situation, like a number of others, presents challenges relating to equality and intergenerational equity. For instance, young people, future generations, Indigenous communities, rural communities, marginalized populations and people in lower income brackets, most of whom may not have contributed significantly to global warming, will live with its consequences.

Canada’s climate is also changing. In a 2019 report, the Government of Canada explained that:

- Canada has warmed and will warm further at about double the rate of the rest of the world, while the rate is even higher in Northern Canada;

- this warming is already having noticeable effects, which will intensify in the future; and

- reducing GHG emissions can limit the extent of warming and its effects, but will not be sufficient to halt global warming or reverse its impacts; it will prevent them from being more severe.[17]

The impacts of climate change—actual and anticipated—have prompted governments around the world to collaborate and to develop plans to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Response to Climate Change

This section outlines global efforts to respond to the challenges of climate change and to try to slow warming, and then presents Canada’s responses and commitments.

Global Response

Most of the world’s countries work together through the United Nations (UN) system to address climate change. Canada is a party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement, which was concluded at the 21st Conference of the Parties—COP 21—in 2015, contains commitments designed to reduce GHG emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.[18]

In particular, the Paris Agreement requires the parties to take actions to limit the increase in the global average temperature to “well below 2°C” and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C above pre‑industrial levels by 2100. The parties set their own GHG emissions reduction targets, which are known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The NDCs are expected both to be updated every five years and to exceed previous targets by aiming to attain greater emissions reductions or to reduce emissions more quickly. In addition to seeking to mitigate climate change, the Paris Agreement also commits the parties to work towards adaptation and climate-resilient development.[19]

At the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP 26), which was held in Glasgow in 2021, about 150 countries committed to increase their efforts to reduce GHG emissions. According to projections, if acted on, the combined total commitments made by all parties to the Paris Agreement to date would limit the increase in the average global temperature to between 1.7°C and 2.6°C above the pre-industrial average by 2100.[20] However, the current policies of all parties to the Paris Agreement would lead to warming of between 2.0°C and 3.6°C above the pre-industrial average.[21] The disparity indicates a need for new policies and actions to implement the pledges made at COP 26. Countries are expected to “revisit and strengthen” the 2030 targets in their NDCs by the end of 2022.

As part of its sixth assessment cycle, the IPCC has released three draft reports recently: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis,[22] Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability,[23] and Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change[24] (the mitigation report). A synthesis report is forthcoming. Each report highlights the urgency for governments to take actions to address climate change. Numerous witnesses indicated that they see the IPCC’s reports as a trustworthy source of information and recommended actions to reduce GHG emissions.[25]

The UN’s Secretary-General, António Guterres, summarized the main message of the mitigation report in the following way: “The science is clear: to keep the 1.5°C limit agreed in Paris within reach, we need to cut global emissions by 45% this decade.”[26]

Canada’s Federal Response

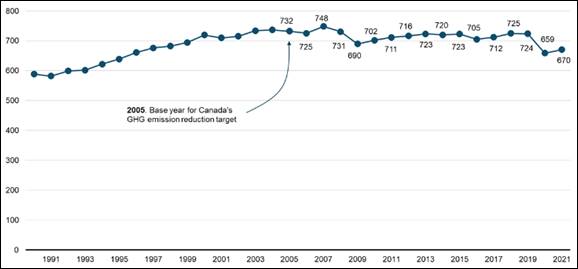

In response to the threats posed by climate change, Canada, like other signatories to the Paris Agreement, has committed to reduce its GHG emissions and take steps to adapt to the anticipated changes. Canada’s current commitment, made in 2021, is to reduce its emissions by 40% to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030, and to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050,[27] that is, from around 730 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2 eq) in 2019 to between 406 and 443 Mt CO2 eq by 2030. In 2021, the last year for which data are available, Canada’s emissions were 670 Mt CO2 eq.[28]

Under the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, the Government of Canada is required to reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to net-zero by 2050, and to create a planning and reporting process for the government to follow as it pursues this reduction.[29] As required by the Act, the government published, on 29 March 2022, the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (2030 ERP).[30] The 2030 ERP highlights measures the government has already implemented, as well as $9.1 billion in new spending that the government has planned to help Canada achieve its emissions reduction goals.

Among the commitments made by the federal government as part of its efforts to reduce GHG emissions are several that relate to the supports for the fossil fuel sector. These are outlined in a later section.

Achieving Net Zero Emissions by 2050

In laying out a scenario illustrating how the world can reach net zero emissions by 2050, the International Energy Agency states that all governments must eliminate fossil fuel subsidies “in the next few years.”[31] The costs of inaction on climate change—that is, the costs of dealing with floods, wildfires, heat domes, melting permafrost, rising sea levels, etc.—are estimated to be very high compared with the costs of supporting a transition to a low-carbon economy that achieves net-zero emissions of CO2 by 2050.[32] Bronwen Tucker, the Public Finance Campaign Co‑Manager at Oil Change International, emphasized this cost difference.[33]

As the Auditor General of Canada stated in a 2017 report, meeting the G20 commitment on fossil fuel subsidies “will have a positive impact on the health of Canadians and the environment by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and wasteful consumption of fossil fuels, and by encouraging investments in clean energy.”[34]

Fossil Fuels and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act received Royal Assent on 21 June 2021, and is intended to affirm the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) as a universal international human rights instrument with application in Canadian law, and to provide a framework for the Government of Canada’s implementation of it.[35] Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, President of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, commented that with the passage of federal UNDRIP legislation, the Committee should hear directly from the Indigenous peoples on whose lands the fossil fuel sector’s activities are taking place.[36] He added,

the Implementing UNDRIP Act recognizes the right of Nations to participate in the governance of their own territories and resources; deciding how the federal government should subsidize the activities of the fossil fuel sector has direct implications on the needs and interests of those Nations, and the committee should make every attempt to include them in these proceedings.[37]

Fossil Fuel Subsidies: Existing Definitions

A number of definitions of “fossil fuel subsidies” have been established. Definitions of fossil fuel subsidies vary in how broadly they include other government supports for fossil fuels. For example, while the World Trade Organization (WTO) definition focuses on financial contributions by government and public bodies, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) also considers what it calls “supports,”[38] in its inventory of support measures for fossil fuels that covers 51 countries and economies. Such supports include any policies that could induce changes in the relative prices of fossil fuels.[39] Analysis from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) goes further, including certain externalities, such as the environmental costs resulting from air pollution from fossil fuel burning, in its assessment of fossil fuel subsidies.[40] Selected definitions are presented in Table 1.

Table 1—Definition of a Fossil Fuel Subsidy From Selected Organizations

Organization |

Definition |

World Trade Organization (WTO) |

A subsidy has “three basic elements: (i) a financial contribution; (ii) by a government or any public body within the territory of a Member; (iii) which confers a benefit. All three of these elements must be satisfied in order for a subsidy to exist.” |

United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) |

Uses the WTO definition |

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) |

The OECD’s approach “measures fossil fuel support as all direct budgetary transfers and tax expenditures that provide a benefit or preference for fossil-fuel production or consumption. The definition of support, as opposed to subsidy, is a deliberately broader one, which encompasses policies that can induce changes in the relative prices of fossil fuels.” |

International Monetary Fund (IMF) |

“Pre-tax consumer subsidies exist when energy consumers pay prices that are below the costs incurred to supply them with this energy.” “Post-tax consumer subsidies exist if consumer prices for energy are below supply costs plus the efficient levels of taxation. The efficient level of taxation includes two components. First, energy should be taxed the same way as any other consumer product. Second, some energy products contribute to local pollution, traffic congestion and accidents, and global warming-efficient taxation requires that the price of energy should reflect these adverse effects on society. In most countries, taxes on energy fall far short of the efficient levels.” “Producer subsidies exist when producers receive either direct or indirect support that increases their profitability above what it otherwise would be.” |

International Energy Agency (IEA) |

An energy subsidy is “any government action that concerns primarily the energy sector that lowers the cost of energy production, raises the price received by energy producers or lowers the price paid by energy consumers.” |

World Bank |

A subsidy for fossil fuels is “a deliberate policy action by the government that specifically targets fossil fuels, or electricity or heat generated from fossil fuels, and has one or more of the following effects:

The definition excludes policy actions that achieve these effects through promotion of efficiency improvement along the supply chain, greater competition in the market, or other improvements in market conditions.” |

Sources: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from World Trade Organization, Subsidies and Countervailing Measures: Overview [note that the full Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures is also available]; Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development, “Methodology,” OECD work on support for fossil fuels; International Monetary Fund, Climate Change: Fossil Fuel Subsidies: Measuring Fossil Fuel Subsidies; International Energy Agency, Carrots and Sticks: Taxing and Subsidising Energy, Report, January 2006; and Masami Kojima and Doug Kaplow, World Bank Group, Fossil fuel subsidies: approaches and valuation, March 2015.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) takes the position that “tax measures for the natural gas and oil industry are not subsidies” but are rather “included to ensure the neutrality of the tax system between sectors that differ in their capital intensity, revenue stream generation, and production/life cycles thereby removing the tax bias against them.”[41]

A number of witnesses stated that the WTO’s definition was well established and widely used internationally;[42] Jason MacLean, who is Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of New Brunswick, and conducts research focused on environmental law, summed the definition up in plain language: “A subsidy is a financial contribution by a government or any public body that confers a benefit.”[43]

The word inefficient, however, does not have a well established definition in this context, as discussed further in the section entitled “Review of the definition of an inefficient subsidy”.

Government of Canada Commitments Related to Phasing Out Support for Fossil Fuels

This study considers two main commitments related to federal support for the fossil fuel sector/industry that have been made by the Canadian Government:

- A 2009 commitment by the Group of 20 (G20) to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

- A commitment to develop a plan to phase out public financing for the fossil fuel sector, which was formalized in several Ministers’ mandate letters in October 2021.

Group of 20 Commitment to Reduce Fossil Fuel Subsidies

In 2009, members of the Group of 20 (G20) countries agreed to work in coordination to reduce fossil fuel subsidies. Following their 2009 summit in Pittsburgh, United States, G20 leaders agreed in the G20 Leaders Statement, to “phase out and rationalize[44] over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support for the poorest.” According to their statement, “[i]nefficient fossil fuel subsidies encourage wasteful consumption, reduce our energy security, impede investment in clean energy sources and undermine efforts to deal with the threat of climate change.”[45] However, as illustrated above, there is no universally endorsed definition of what an inefficient fossil fuel subsidy is. This is discussed further in a later section.

Canada’s initial G20 commitment was to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies by 2025,[46] but this timeline was accelerated in 2021, with a goal of completing the task by 2023.

Eliminating Subsidies and Phasing Out Public Financing for Fossil Fuels: Commitments Announced in Ministerial Mandate Letters

In December 2021, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Mandate Letter instructed the Minister of Environment to work with the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, with the support of the Minister of Natural Resources, “to accelerate our G20 commitment to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies from 2025 to 2023, and develop a plan to phase out public financing of the fossil fuel sector, including by federal Crown corporations.”[47] The Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Mandate Letter[48] gave the same instructions and added that flow-through shares for oil, gas and coal should be eliminated. Their elimination was to be completed by 31 March 2023.[49]

Flow-through shares are described as follows: “A flow-through share allows a corporation to obtain financing for expenditures on exploration and development in Canada. By issuing flow-through shares, a company can ‘flow through’ certain expenses to the share purchaser. These expenses are then deemed to have been incurred by the investor,[50] not the corporation, which can reduce the investor’s taxable income.”[51]

The federal government has also made other, related commitments and statements; a selection of these is summarized in Table 2, along with the two being studied here.

Table 2—International Commitments and Statements Made by Canada’s Federal Government to Address “Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies”

Date |

Commitment or Statement |

Context |

Sept. 2009 |

“[P]hase out and rationalize over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support for the poorest.”[52] |

G20 Summit in Pittsburgh, USA |

May 2012 |

“In addition, we strongly support efforts to rationalize and phase-out over the medium term inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption, and to continue voluntary reporting on progress.”[53] |

G8 Summit in Camp David, USA |

Sept. 2015 |

In 2015, Canada and 192 other United Nations (UN) member states adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (the 2030 Agenda), which is a global framework for achieving 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). SDG 12, which concerns responsible consumption and production patterns, has 11 targets. One of these, known as Target 12.C, is to “rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption by removing market distortions, in accordance with national circumstances including by restructuring taxation and phasing out those harmful subsidies, where they exist, to reflect their environmental impacts.”[54] A 2019 report from UNEP[55] outlines the methods used to assess the indicator for this target. |

Agenda 2030 (Sustainable Development Goals) |

Nov. 2021 |

Parties are called on to accelerate “efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition”[56] |

COP26—Glasgow Climate Pact |

Nov. 2021 |

“[P]rioritise our support fully towards the clean energy transition” and “further prioritize support for clean technology and end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil fuel sector by the end of 2022, except in limited and clearly defined circumstances that are consistent with the 1.5 degree Celsius warming limit and the goals of the Paris Agreement.”[57] |

Statement on International Public Support for the Clean Energy Transition[58] (made at COP26)—referred to as “Glasgow Commitment” |

Dec. 2021 |

“[A]ccelerate our G20 commitment to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies from 2025 to 2023, and develop a plan to phase out public financing of the fossil fuel sector, including by federal Crown corporations”[59] |

Ministerial Mandate Letters |

Source: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament.

Views on Phasing Out Government Support

No witnesses or briefs expressed concern that the federal government had phased out a number of fossil fuel supports over recent years. Tristan Goodman, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, noted that the production of oil and natural gas, which had warranted government support 30 to 50 years ago, no longer required such support.[60] Not all witnesses supported the idea of eliminating subsidies and supports altogether, however.

Ben Brunnen, who is Vice-President of Oil Sands, Fiscal and Economic Policy at CAPP, pointed out that Canadian [federal and provincial] governments currently benefit from taxes and royalties paid by fossil fuel companies: “Limiting access to capital or increasing taxes will only have negative effects on Canada's economy, energy affordability, emissions reduction progress and global energy security,” he stated, indicating that “total government revenues for our industry could be as high as $20 billion this year, including $5 billion in unanticipated incremental federal revenue.”[61]

Mark Agnew, the Senior Vice-President of Policy and Government Relations at the Canadian Chamber of Commerce, commented that immense capital investment is needed in the transition to net zero, and that the transition would be much more difficult if oil and gas companies did not have access to tax credits for carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) or initiatives like the Net-Zero Accelerator.[62] Heather Exner‑Pirot, a Senior Policy Analyst at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, spoke about government funding programs that have helped the fossil fuel sector to reduce its emissions, and felt that such programs should be continued because they can support reduction of GHG emissions and access to affordable energy.[63] Mr. Agnew also felt that businesses need “predictability in the funding streams that [they] can tap into,”[64] suggesting making the Net-Zero Accelerator initiative a permanent source of funding. If oil and gas companies did not have access to such initiatives, he said, the transition towards net zero would be much more difficult.[65]

Ben Brunnen mentioned the decreasing emissions intensity of Canadian oil and gas extraction, and the commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 made by the Oil Sands Pathways Alliance,[66] suggesting that global emissions could be lower if Canadian oil and gas were used instead of more carbon-intensive fuels from elsewhere.[67]

Figure 1—Emissions per million barrels equivalent from Canadian oil and gas production, in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2 eq)/million barrels equivalent

Source: Prepared by the Committee with data from: Government of Canada, Options to cap and cut oil and gas sector greenhouse gas emissions to achieve 2030 goals and net-zero by 2050—discussion document.

On the other hand, many witnesses and authors of briefs felt it was important to phase out subsidies and public financing for fossil fuels, arguing that such supports slow and hinder the transition to renewable energy, which they saw as necessary and urgent for reducing the impacts of climate change[68] and that they felt that these tax dollars could be better employed by direct investment in, or subsidies to, the renewables sector.

Jason MacLean shared an opinion based on his work:

Climate modelling now shows that, in order to have only a 50% chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial norm, rich producer countries, including Canada, must cut oil and gas production by 74% by 2030 and completely phase out oil production by 2034. Removing all fossil fuel subsidies is an important step toward this larger climate and energy policy goal.[69]

Jerry DeMarco, who is the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development in the Office of the Auditor General, pointed out that “[d]espite repeated government commitments and plans to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, they increased by more than 20% from 1990 to 2019. Urgent actions are needed to reverse this trend.”[70] Annie Chaloux, who is Associate Professor and Climate Policy Specialist at the Université de Sherbrooke, David Gooderham, and Eddy Perez, who is the International Climate Diplomacy Manager at Climate Action Network Canada agreed, the latter stating that eliminating fossil fuel subsidies can help “reduce global GHG emissions by as much as 10% by 2030.”[71]

Figure 2—Canada’s Greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2021, in megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (Mt CO2 eq)

Source: Government of Canada, Greenhouse gas emissions.

Joy Aeree Kim, who is Lead of Fiscal Policy at UNEP, explained that countries around the world are struggling to respond to the pandemic, build resilience to climate change, and get back on track to achieving the sustainable development goals, and that “reform of fossil fuel subsidies represents a large potential source [of funds] for social and green investment.”[72] She suggested that “just 10% to 30% of global fossil fuel subsidies could pay for the transition to a clean economy at the global level.”[73]

Dale Beugin, Vice-President of Research and Analysis at the Canadian Climate Institute, told the Committee that phasing out fossil fuel subsidies makes economic sense as much as environmental sense: Countries and firms representing 90% of global gross domestic product (GDP) have committed to achieving net zero, he noted, and if they follow through on those commitments, “that represents a seismic shift in demand for fossil fuel products and absolutely changes the long-term payoffs of investments, both public and private, in the sector.”[74] The global transition to a low-carbon economy is “a structural shift, not a temporary shock,” he said, and the government needs to develop strategies that help the affected sectors and regions to prepare to thrive in the emerging low-carbon economy, rather than attempting to insulate them from market change.”[75] He added:

[T]he fossil fuel sector is no longer the secure source of economic growth and job creation that it once was. Coal, oil and gas demand will decline globally, though there is uncertainty on the timing and slope of that decline over the next decade. Public investment in long-lived fossil fuel assets now carries more risk and less certain benefits for society, even within the context of current upheavals in energy markets.[76]

One brief summarized input from over eight thousand people who expressed almost unanimous support for ending all fossil fuel subsidies and 84% support for expanding the definition of a fossil fuel subsidy to include all public financing and other fiscal support provided to the oil and gas sector.”[77]

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada continue taking steps to eliminate subsidies and applicable public financing for the fossil fuel sector by the end of 2023, with careful attention to and mitigation of any potential social and economic impacts.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada ensure that Canada’s commitment to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies aligns with and provides policy coherence to Canada’s domestic public financing policy.

Review of the Definition of an Inefficient Subsidy

Definitions Used by Government Departments and Agencies

Government departments’ efforts to define inefficient fossil fuel subsidies have been audited several times by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development (CESD). The CESD’s 2017 reports found that neither Finance Canada nor Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) had a clear definition of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies. “Without a clear definition of what it is they've committed to phasing out, it's hard to phase that out,” noted the current CESD, Jerry DeMarco.[78]

Mr. DeMarco added that “[i]n 2019, we found that Finance Canada still did not have a clear and meaningful definition of inefficient. It focused on fiscal and economic considerations, but did not consider economic, social and environmental factors, which are components of sustainable development in decision-making on fossil fuel subsidies over the short, medium and long term.”[79]

When asked about the status of the definition that the department is working on, ECCC officials did not provide a precise timeline for when the definition of “inefficient” would be ready. Hilary Geller, the Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy Branch at ECCC, said, “[w]e're on a timeline to be able to provide advice to the government so that it can make decisions in time to have the phase-out of the non-tax inefficient fossil fuel subsidies done in 2023, as per their mandate commitments.”[80]

Mairead Lavery, President and Chief Executive Officer of Export Development Canada (EDC), said that EDC’s work “with our partners is to ensure we are really supporting commercial partners, like our banks, and ensuring that we're not conferring a subsidy. We are at market rates.”[81] She said she was not aware of the internationally agreed-upon definition of a subsidy[82] but stated that EDC does not provide grants or subsidies.[83]

Canada’s Consultation Process on Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Witnesses did not mention it during the study, but in 2019, ECCC held a three-month consultation process on the government’s draft framework that could be used to identify inefficient, non-tax fossil fuel subsidies.[84] The associated Discussion Document for Canada’s Assessment Framework of Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies proposed the following definition: “non-tax fossil fuel subsidies are defined as federal non-tax programs that provide preferential treatment that specifically supports the production or consumption of fossil fuels.”[85]

The discussion document also suggested criteria to consider when assessing the efficiency of an identified non-tax fossil fuel subsidy. These included consideration of alternative delivery mechanisms that could achieve the same policy outcome(s), of whether a measure intends to achieve social, economic, and environmental objectives, and of whether alternatives to the measure could achieve the same objective(s) more effectively, more efficiently, and/or in a more equitable manner.[86]

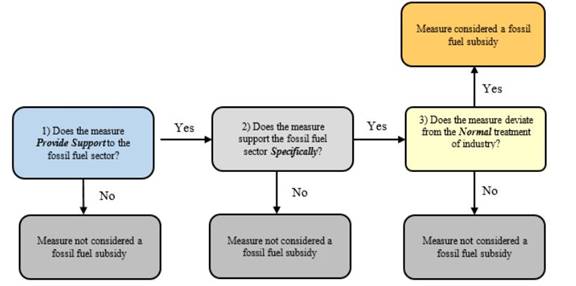

The discussion document also describes ECCC’s assessment process for 36 non‑tax measures to determine if they were inefficient fossil fuel subsidies (illustrated in Figure 3).

Figure 3—Flowchart of Environment and Climate Change Canada’s 2019 Assessment Process to Identify Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada, Discussion Document for Canada’s Assessment Framework of Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies, p. 8.

Of the 36 measures assessed, four were found to be subsidies, as outlined in Table 3. None of these four subsidies was found to be inefficient and, therefore, none would need to be phased out “within the scope of the G20 commitment.”[87]

Table 3—Four Remaining Fossil Fuel Subsidies Identified by ECCC in 2019 of the List of 36 Measures Assessed to Identify Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies

Federal Department Responsible |

Program Name |

Type of Measure |

Indigenous Services Canada |

Electricity Price Support for Indigenous Communities |

General Program Support |

Natural Resources Canada |

Electric Vehicle and Alternative Fuel Infrastructure Deployment |

General Program Support |

Natural Resources Canada |

Petroleum Technology Research Centre (a not-for-profit founded in 1998 by NRCan, the Government of Saskatchewan, University of Regina, and Saskatchewan Research Council, to “facilitate research, development and demonstration projects to reduce the carbon footprint and increase the production of subsurface energy.[88]”) |

Technology and research development programs |

Natural Resources Canada |

Oil and Gas Clean Tech Program (ended 2017–18) |

Technology and research development programs |

Source: Extracted from: Environment and Climate Change Canada [ECCC], Discussion Document for Canada’s Assessment Framework of Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies, pp. 14–16.

Other Views on Definitions

Many witnesses had views on the interpretation of “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies. Grand Chief Stewart Phillip commented that a commitment to phase out “inefficient” subsidies for “unabated” fossil fuel use, is much too vague, and “leaves an incredible amount of wiggle room for the industry to continue fueling the climate crisis and delaying real emissions reductions.”[89]

Jason MacLean stated that “[t]here is no basis in international law or policy for distinguishing between efficient and inefficient subsidies, nor is there any basis for adopting a narrow definition of the term “subsidy” in relation to fossil fuels.”[90]

Joy Aeree Kim drew attention to a 2019 UNEP report[91] that defines fossil fuel subsidies, pointing out that while some G20 members have developed other definitions, there is, already, an internationally agreed upon definition of and methodology for measuring and reporting on fossil fuel subsidies, which was adopted by the UN Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDGs.[92] UNEP, as custodian agency of SDG 12.1.C, developed the methodology, together with the OECD: “It [is] an internationally agreed upon definition and methodology that was actually recommended to all of the member countries to follow,” she said.[93]

Ben Brunnen noted that what he called “clean-tech investment supports” such as CCUS and the Net-Zero Accelerator could be identified as “efficient in the sense that they are working towards achieving investment in technologies that will reduce emissions.”[94] Julia Levin, who is Senior Climate and Energy Program Manager at Environmental Defense Canada, saw the $8 billion dollar Net-Zero Accelerator as a potential source of fossil fuel subsidies, and recommended that “strict climate conditions” or legislation be applied to ensure that this did not happen.[95]

Mark Agnew suggested that the precise definition may not matter as much as the policy intention: “The risk is that we spend a lot of time chasing our tails in trying to define it but not really getting to the nub of the issue,”[96] he said. Several other witnesses shared the idea that this definition itself is less important than the framework for deciding how to spend public dollars, as outlined below.

Jerry DeMarco suggested that the main action required is for Canada to assess all of its supports for the fossil fuel industry against how they will “foster or hinder Canada’s transition to net-zero emissions,”[97] rather than dwelling on definitions.[98] He acknowledged that Canada made a commitment in 2009 to remove inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, but emphasized that the more important focus should be on choosing policy measures that reduce GHG emissions. Simon Langlois-Bertrand, who is a Research Associate at the Trottier Energy Institute, and Aaron Cosbey, who is Senior Associate at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, agreed.[99] Aaron Cosbey said:

The really important question is not, is this dollar spent on a subsidy? The really important question is, is this dollar spent in a way that is a good use of public funds? The criterion for that is not the same as whether it's a subsidy or not; the criterion is whether it is in line with our Paris Agreement targets. Is it an efficient use of funds, considering the target? Are there better ways you could use that money and are you contributing to the risk of stranded assets? Those are the kinds of criteria we really need to be worrying about.[100]

Simon Langlois‑Bertrand emphasized that government support for industry should be conducive to achieving decarbonization targets and should ensure continued support for industries and populations affected by the energy transition.[101] This cannot include renewal or expansion of infrastructure that favours the maintenance or increase of greenhouse gas emissions, he clarified, such as the natural gas network, heating infrastructure based on fossil fuels; and vehicles using fossil fuels.”[102]

Dale Beugin referenced a recent paper published by the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices,[103] which assessed whether government measures support or hinder “Canada's long-term economic growth and a smooth transition for workers and communities, especially in the face of the accelerating decarbonization in global markets.”[104] Rather than focusing on definitions of “subsidy” and “inefficiency,” he explained, they opted to assess policy according to four key criteria: “transition consistency, value for money, employment outcomes and policy fit.”[105]

In a brief published after the Committee had finished hearing from witnesses, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) recommended the following criteria for assessing the efficiency of fossil fuel subsidies in Canada: “alignment with climate commitments; support for the low carbon economy; just transition consistency; [and] the best way to achieve the overall policy goal.”[106]

Jerry DeMarco suggested that Canada needs to assess all of its supports for the fossil fuel industry against how they will foster or hinder Canada’s transition to net-zero emissions.[107]

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada assess planned and proposed policy measures based on whether they support or hinder Canada's long-term economic growth and a smooth transition for workers and communities, especially in the face of the accelerating decarbonization in global markets.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada take steps to ensure that public funds cannot be invested in any energy infrastructure that is at risk of becoming a “stranded asset” during the energy transition.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada ensure that any subsidy it offers facilitates the transition toward a low-carbon future, and is consistent with Canada’s 2026 emissions objective, 2030 emissions reduction goals and its 2050 net zero emissions goals.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada adopt:

- a broad, internationally recognized definition of a fossil fuel subsidy; and

- a definition of “inefficient,” in the context of fossil fuel subsidies.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada develop a framework for decision-making related to supports for the oil and gas industry that is based on analysis and assessment of the most cost-effective way to achieve greenhouse gas reductions while considering the needs of workers and communities.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada, inclusive of Canadian Crown Corporations, publish, before the end of 2023, its plan to phase out public financing of the fossil fuel sector, and that the plan be ready for implementation.

Progress to Date: Phasing Out Public Financing of the Fossil Fuel Sector, Including by Federal Crown Corporations

Mandate letters from 16 December 2021 asked three Canadian ministers to develop a plan to phase out public financing of the fossil fuel sector, including by federal Crown corporations. The Committee heard that work on the public financing commitment is still at the planning stage.[108] In December 2022, the Government of Canada announced that it would end new direct public support for international unabated fossil fuel energy by the end of that year; it also “recognized the need to eliminate inefficient fossil fuel subsidies domestically” and committed to “eliminating additional significant fossil fuel subsidies early in 2023.”[109]

EDC, which is a crown corporation, is taking steps to reduce its support for the fossil fuel sector, and Hillary Geller noted that ECCC anticipated that EDC would be included when work begins on the plan to phase out public financing for the fossil fuel sector.[110] A selection of EDC’s steps to shift its financing to respond to climate change are outlined in a later section.[111]

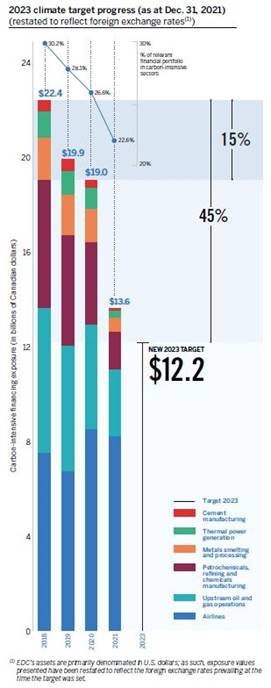

Export Development Canada’s Supports for the Fossil Fuel Sector

In 2022, EDC announced a target of 45% reduction in financing exposure to the six most carbon-intensive sectors below 2018 levels by 2023 (as shown in Figure 4). EDC considers the six following sectors to be carbon intensive:[112]

- airlines;

- upstream and oil and gas operations;

- petrochemicals, refining and chemicals manufacturing;

- metals smelting and processing;

- thermal power generation; and

- cement manufacturing.[113]

In EDC’s determination, these carbon-intensive sectors are “more susceptible to higher risks related to a transition to a low-carbon economy.”[114] Risks EDC identifies from the transition to a low-carbon economy include:

[P]olicy and legal risks such as policy constraints on emissions, imposition of carbon tax and other applicable policies; water or land use restrictions or incentives; shifts in demand and supply due to technology and market changes; and reputation risks reflecting changing customer or community perceptions of an organization’s impact on the transition to a low-carbon and climate resilient economy.[115]

Figure 4 shows that EDC disbursed $13.6 billion in 2021 supporting businesses in carbon-intensive sectors—less than in any of the previous three years.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada attach strict conditions to all funding programs to ensure government spending is aligned with Canada’s obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Figure 4—Representation of EDC’s current target to reduce financing exposure to the six most carbon-intensive sectors to 45% below 2018 levels by 2023, showing its relative levels of financing to those sectors

Source: EDC, EDC Net Zero 2050, July 2022.

EDC’s climate change policy,[116] adopted in 2019, specifies that EDC will no longer finance new coal-fired power plants (unless they include carbon capture and storage technologies), new coal mines, thermal coal mining operations or companies that generate more than 40% of their revenue from thermal coal generation.[117] EDC’s climate change policy and associated changes began before the federal government indicated an intention to phase out public supports for fossil fuels.

Several witnesses said that EDC’s support for the sector should be seen as a subsidy.[118] Bronwen Tucker opined:

The most egregious federal production subsidy in Canada is Export Development Canada's $13.6 billion a year, on average, in government-backed and often preferential support for oil and gas. EDC's activities mean that Canada gives the most trade and development finance to fossil fuels of any country in the G20. This EDC money also contributes heavily to Canada's worst ranking score among OECD G20 countries for all oil and gas production subsidies. Ultimately, it means that more oil and gas projects go forward than would otherwise be possible.[119]

When asked which subsidies she would like to see removed, Julia Levin named EDC’s support to the fossil fuel sector, which she said it is the greatest part of the federal government’s support to the sector, even if not officially designated a subsidy.[120]

In 2020 and 2021, respectively, EDC facilitated business valued at approximately $8.1 billion and $5.1 billion in the oil and gas sector—facilitating business could include offering loans, other financing, or insurance products.[121] Mairead Lavery explained that EDC’s approach to oil and gas has evolved:

In just three years, between 2018 and 2021, EDC's support for this sector has decreased by approximately 65%. EDC has committed to cease any new financing to international fossil fuel companies or their projects by the end of this year.[122]

She stated that EDC provided financial support to the oil and gas industries in 2021, but that it does not provide subsidies.[123] She also stated that EDC will divert its attention to the support of Canadian companies. She explained that EDC is

really working with the industry to understand their own pathway. Many of the Canadian oil and gas companies have signed up to a net-zero commitment. We want to work with them to understand what that means, what that means for technology, for clean technology in particular, and their investments in research and development, so that we can be with them on that journey as they work towards a low-carbon future.[124]

However, while it has committed to withdrawing from supporting international unabated fossil fuel projects, EDC has not made such a commitment related to Canadian projects; rather, it will “continue to review” its support for them.[125]

Ms. Lavery said that EDC is one of Canada’s largest financial backers of clean technology, and that in 2021, for the first time—in what she expects to be a trend—its support for clean technology surpassed its support for the oil and gas sector, without, however, providing details in her testimony.[126] Correspondence from EDC clarified that “[i]n 2021, EDC facilitated $6.3 [b]illion in cleantech business and $4.4 [b]illion in the [o]il and [g]as sector.”[127] EDC’s definition of clean technology is any process, product or service that reduces environmental impacts through:

- environmental protection activities that prevent, reduce or eliminate pollution or any other degradation of the environment;

- resource management activities that result in the more efficient use of natural resources, thus safeguarding against their depletion; and

- the use of goods that have been adapted to be significantly less energy or resource intensive than the industry standard.[128]

Mairead Lavery explained that the definition is broad and can include support for fossil fuel companies.[129] EDC offers a new “sustainable bond framework” that includes what EDC considers to be “social as well as transition financing projects,” which can involve funding for fossil fuel companies.[130] Ms. Lavery called this a “transition bond,” adding that it allows EDC to “get in and help these companies move faster toward reducing their GHG emissions.”[131] She said EDC could use its leverage to help existing companies change faster, by requiring certain disclosures and a transition plan. She added that companies’ plans must have interim targets and be monitored—they cannot only have a 2050 net zero goal.[132]

Ms. Lavery indicated that support for Canadian oil and gas projects aims to ensure

that the financing is going towards transition-type products. This is capital expenditure specifically focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Actually having the capacity there, we hope will make sure that they put in place that capital expenditure faster.[133]

She clarified that it can be hard for such companies to find financing for support for “early adoption of technology.”[134]

When asked about EDC’s support for renewable energy projects, as compared with emissions reduction in fossil fuel projects, Ms. Lavery said “[w]e have looked at our portfolio of the future and indicated how we would like to pivot that. That results in the teams having very clear capital allocations for the purposes of clean technology.”[135]

To ensure sound long-term investment decisions and avoid the possibility of financing assets that later become stranded, EDC “has been working on climate stress tests.”[136]

Progress to Date: Phasing Out Fossil Fuel Subsidies by 2023

Hilary Geller of ECCC noted that there has been “significant progress in meeting the government's commitment to eliminate and rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies in the tax sector.”[137] Miodrag Jovanovic, Assistant Deputy Minister, Tax Policy Branch, Department of Finance, affirmed that since 2007, phase-out has begun or been announced for nine tax measures, including the proposal in Budget 2022 to finalize the phase-out of the flow-through shares for oil, gas and coal exploration.[138] Ben Brunnen confirmed that the federal government no longer provides production subsidies for the sector.[139]

Work to reduce fossil fuel subsidies was already underway in previous parliaments. For example, ECCC describes at least eight tax benefits for the fossil fuel sector that were phased out or rationalized between 2015 and 2021.[140] In a brief, CAPP stated that the federal government has been phasing out subsidies over the last 19 years. Government actions to eliminate subsidies are listed in Table 4.

Table 4—Timeline of Government of Canada Commitments and Actions to Phase Out Fossil Fuel Subsidies and Supports

Year |

Action |

Budget 2003 |

Phase-out of a tax preference for fossil fuel production: provisions relating to the resource allowance* |

Budget 2007; completed 2015 |

Phase-out of a tax measure: accelerated capital cost allowance for oil sands** |

Budget 2011; completed 2016 |

Phase-out of tax measure: reduction in deduction rates for intangible capital expenses in oil sands projects to align with rates in the conventional oil and gas sector** |

Budget 2012; completed 2017 |

Phase-out of tax measure: the Atlantic Investment Tax Credit for oil and gas mining** |

Budget 2013; completed 2018 |

Phase-out of tax measure: Reduction in the deduction rate for pre-production intangible mine development expenses to align with the rate for the oil and gas sector** |

Budget 2013; completed 2021 |

Phase-out of tax measure: accelerated capital cost allowance for mining** |

Budget 2016 |

Phase-out of a tax measure: accelerated capital cost allowance for liquefied natural gas facilities to expire as scheduled in 2025** |

Budget 2017; completed 2019 |

Phase-out of tax preference allowing small oil and gas companies to reclassify certain development expenses as more favourably treated exploration expenses*** |

Budget 2017; completed 2021 |

Rationalization of the tax treatment of expenses for successful oil and gas exploratory drilling*** |

2019 (public consultation) |

Public consultation occurred from March to June on the Government’s draft framework to review fossil fuel subsidy measures outside the tax system (led by ECCC)*** |

Budget 2022 |

Proposed to eliminate the flow-through share regime for fossil fuel sector activities (for flow-through share agreements entered into after 31 March 2023)*** |

Sources: Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), 2017 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada, “Report 7—Fossil Fuel Subsidies”; Environment and Climate Change Canada, Discussion Document for Canada’s Assessment Framework of Inefficient Fossil Fuel Subsidies, pp. 4–5; Environment and Climate Change Canada, Briefing materials for Appearance before the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—May 3, 2022, “Inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”; Prime Minister of Canada, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance Mandate Letter, Minister of Environment and Climate Change Mandate Letter, Minister of Natural Resources Mandate Letter, 16 December 2021.

Note: Primary reference indicated for each line as follows: *OAG 2017, **ECCC 2019, ***ECCC 2022.

When questioned about the Department of Finance’s process, Miodrag Jovanovic noted that industry is always given time to adapt, and that social and economic impacts, including impacts on jobs, are always assessed when the Department considers eliminating any support:[141]

If there's any doubt as to the importance of the potential effect of phasing out a specific subsidy, that's where the design of the phase-out and the time we give industry to adjust becomes quite important. … [V]ery often there is a substantial period that is being provided to adjust.[142]

In contrast to the government’s analysis, other organizations have described Canada’s fossil fuel subsidies as being significant in size, but difficult to assess.

The CESD and the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) conducted audits and studies on fossil fuel subsidies in Canada in 2012, 2017 and 2019. The investigations all found that the departments had not defined “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”

In their studies and audits in 2012,[143] 2017,[144] and 2019,[145] the CESD and OAG studied the government’s commitment on fossil fuel subsidies.[146] Each study found that departments had been unable to complete the work, in part because they had not clearly defined an inefficient fossil fuel subsidy.

In November 2021, the CESD published an audit report focused on the Onshore Program of NRCan’s Emissions Reduction Fund for the oil and gas sector, which found that the program’s interest-free and non-repayable loans for oil and gas companies were examples of subsidies.[147] It criticized the program’s design because it did not link funding to net emissions reductions from oil and gas operations.[148]

Jerry DeMarco noted that a key part of the departments’ responses to the CESD audits was that there were going to undertake a peer review with Argentina, as announced in 2018, however, no update on the progress of this review had yet been made at the time of his testimony.[149] The Government of Canada has stated that the voluntary peer reviews among G20 countries working to reform fossil fuel subsidies “will enable both countries to compare and improve knowledge, and push forward the global momentum to identify and reduce inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.”[150] Other witnesses drew attention to the anticipated peer review as well.[151]

Several witnesses commented that they considered the Government of Canada’s support for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project (TMX) to be a fossil fuel subsidy that should be ended.[152] One witness deferred to ECCC’s analysis and therefore does not see it as a subsidy[153] and one witness approved of the government’s support for the project because it could provide stable, predictable revenues for Indigenous communities.[154]

Recommendation 10

That Natural Resources Canada ensure that, for onshore projects, the Emissions Reduction Fund only considers projects that fully eliminate methane emissions.

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada complete and publish its fossil fuel subsidy peer review with Argentina as quickly as possible.

Quantifying Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Canada

It can be difficult to provide a definitive valuation for fossil fuel subsidies in Canada, given the range of definitions, and delays in availability of data. However, the IISD has prepared some inventories of fossil fuel subsidies in Canada as part of its Global Subsidies Initiative. The IISD uses the WTO definition of subsidies in this inventory.[155]

The IISD estimated that fossil fuel subsidies in Canada in fiscal year 2019–2020 were worth nearly $600 million, but would be higher if subsidies for which publicly available data were lacking, such as tax‑related subsidies, could be included.[156] The authors noted that fossil fuel subsidies at the federal level were primarily directed to fossil fuel producers, as opposed to consumers, and that Canadian subsidies have shifted “from an emphasis on exploration to one on the development of infrastructure for fossil fuel production and exports.”[157] They also pointed out that “[i]nformation on subsidies should be more transparent to allow for a more comprehensive inventory.”[158]

The IISD inventory for 2020 found that in that year the Canadian government had provided at least $1.91 billion in fossil fuel subsidies,[159] noting that this figure is an underestimate because insufficient data is available to fully document the level of federal subsidies. The jump of over 200% from 2019 levels was mostly due to support measures that were introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, a direct transfer supported Newfoundland’s offshore oil industry,[160] and federal funds of up to approximately $1.7 billion were transferred to certain provinces and the Alberta Orphan Well Association to help with the clean-up of orphan and inactive oil and gas wells.[161] Stephen Buffalo, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Indian Resource Council Inc., and Heather Exner‑Pirot both noted several benefits of the orphan well funding: it had helped to clean up First Nations land, and had employed 250 young First Nations people, and had ended methane leaks.[162] Julia Levin said it would have been good use of public funds had the money gone directly to First Nations, but that the lion’s share went to large companies, which then paused their own funding and used public dollars.[163] Dale Beugin was of the view that support for orphan well clean-up should be temporary and “targeted at firms most at risk of bankruptcy.”[164]

A report from the IMF determined that, when externalities were included, Canada provided $U.S. 43 billion to the oil and gas sector in 2015.”[165] A 2021 update found a number closer to $U.S. 63 billion.[166]

In the OECD inventory of support measures for fossil fuels, many measures listed for Canada have been phased out since 2006 or 2010.[167] The main measure currently listed for Canada is a tax expenditure, “flow-through share deductions,” which decreased:

- from approximately $292 million in 2011 to about $7.8 million in 2021 for crude oil;

- from almost $4 million in 2011 to about $65,000 in 2021 for “natural gas liquids;” and

- from $9.3 million for natural gas in 2011 to about $157,000 in 2021.[168]

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers argued in its brief that “remaining oil and gas tax measures are part of the benchmark tax system, therefore not subsidies pursuant to our G20 commitment.”[169] Estimates generally include a caveat because not all data is available; however, Table 5 presents some of the estimates.

Table 5—Estimates of Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Canada

Source |

2019 Estimate |

2020 Estimate |

2021 Estimate (if available) |

Notes |

Fossil Fuel Subsidy Trackera |

2.252 billion USD |

3.924 billion USD |

3.190 billion USD |

Based on data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

International Institute for Sustainable Development |

0.6 billion CADb |

1.91 billion CADc |

n/a |

Includes only federal subsidies, not provincial ones. These figures refer to data from each calendar year. |

Sources: OECD, OECD work on support for fossil fuels: Methodology.

- a) Fossil Fuel Subsidy Tracker, “Country: Canada.” Accessed May 8, 2023.

- b) Vanessa Corkal, Julia Levin and Philip Gass, International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), Canada’s Federal Fossil Fuel Subsidies in 2020, February 2020, p. 1.

- c) Vanessa Corkal, International Institute for Sustainable Development, Federal Fossil Fuel Subsidies in Canada: COVID-19 edition, February 2021, p. 1.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada make information about subsidies and supports to the fossil fuel sector transparently available, to allow for a more comprehensive inventory and analysis.

How the Government of Canada Can Meet its Climate Commitments

In discussing the planned phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies and supports, many witnesses put considerable time and effort into contextualizing their comments with suggestions of how Canada could meet is emissions reduction targets and contribute most effectively to its Paris obligation of holding global temperature increase to no more than 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial average by 2100.

Some of the main themes witnesses addressed are presented in this section.

Just Transition

Many witnesses who supported the concept of a “just transition” offered suggestions on how to move forward to ensure that climate commitments are met in a fair and inclusive way, providing high quality employment opportunities, including for those currently working in the fossil fuel sector, and most importantly leaving no one behind.[170] In its brief, LeadNow explained that over 43,000 people from across Canada had signed petitions “demanding a Just Transition to tackle the climate crisis and inequality, by investing in communities and creating secure jobs that are also good for the planet.”[171]

Bronwen Tucker said a just transition would “protect […] workers and communities rather than locking in climate chaos.”[172]

Larry Rousseau, Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Labour Congress, explained that the Canadian Labour Congress represents three million workers, including tens of thousands working “in the fossil fuel industry” and is a long-time supporter of just transition measures. He noted:

[E]nergy and resource sector workers already understand the grim reality of climate change. They are living it. They get the need to transition to clean and renewable sources of energy, but they insist, and we insist, that the transition [benefit] workers instead of occurring at their expense.[173]

He emphasized the need for a role for workers and unions in discussions and decisions that affect “their future and the economic future of their communities.”[174]

Aaron Cosbey added that any spending of public funds that results in more investment in oil and gas sectors will build up assets that are at risk of being stranded, which can compromise a just transition: He explained that, according to the IISD’s 2021 report, “In Search of Prosperity,”

post-2030 global demand for oil is going to be in secular decline, with low and volatile prices. If we don’t properly manage the rampdown of investment and production in that sector, the economic impacts are going to be acutely painful for oil-dependent regions, communities and workers.[175]

Public dollars are better spent on “reskilling, upskilling and generous relocation packages for oil and gas workers and their families” than on subsidies to the [fossil fuel] sector, said Justin Leroux, who is Professor of Applied Economics at HEC Montréal and Co‑Director, Ethics and Economics at Centre de recherche en éthique.[176]

Support for Renewable Power and Clean Energy

A few witnesses were skeptical that renewable energy could meet societal needs,[177] or said it was too expensive,[178] but several other witnesses stated that support for renewable energy was an essential and plausible solution, citing analysis by organizations such as the IEA.

Julia Levin said that Canada is below its potential in non-hydro renewable energy capacity and building new renewable energy power is cheaper than running existing fossil-fuel-based energy production.[179] “In terms of job creation and co-benefits, cleaner air and jobs in every community across the country, there's no question that investing in renewables is necessary.”[180]

Normand Mousseau, Scientific Director of the Trottier Energy Institute and Full Professor at Polytechnique Montréal, said that subsidies “must facilitate the transition to low‑carbon energy.”[181] Christina Hoicka, Canada Research Chair in Urban Planning for Climate Change and Associate Professor at the University of Victoria, noted, “[a]ccording to the Organization of Economic Co‑operation and Development and the International Energy Agency's “Clean Energy Technology Guide,” there are at least 38 technologies, including a range of renewable energy technologies, that are market ready and could be scaled immediately with the right supports.”[182] She added that investing in technologies that are part of a clean energy transition would be a more effective use of scarce public dollars than funding the oil and gas sector.[183]

Christina Hoicka said that Canada needs to support these proven technologies to a greater extent, or it won’t be able to meet its climate goals. She acknowledged the challenge of providing sufficient electricity transmission to cities for electrification of vehicles and growth of population, buildings and industry, but was confident that with the right mix of policy instruments, administrative support for programs, and support for communities to participate meaningfully, it is possible, and “can be done in a socially and economically just manner.”[184] She explained that her research has shown that one way to bring down costs and increase reliability is to combine “clusters of innovations.”[185]

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada support renewable energy innovation to demonstrate the potential for an affordable, clean energy transition.

In contrast, the view of Craig Golinowski, who is President and Managing Partner of Carbon Infrastructure Partners Corp., was that it is “simply impossible to rally the magnitude of capital needed to invest in sufficient alternative energies.”[186]

Bronwen Tucker explained that an October 2021 report[187] released by Friends of the Earth U.S. and Oil Change International showed that on average, G20 countries as a whole provided 2.5 times more support for fossil fuels than for renewable energy from 2018 to 2021; while in Canada it has been over 14 times more.[188] This indicates that public finance for oil and gas really needs to be phased out, she and others concluded.[189]

Christina Hoicka said that she believes Canada can meet its targets, “if we follow the evidence on our fastest, cheapest options, which also improve social and economic benefits.”[190] For example:

Critical and technologically viable opportunities for decarbonization [which] include electrification of transportation; deep energy retrofits to buildings, … including heat pumps; and the rapid scale-up of waste heat capture for heating and cooling processes in cities and industrial districts.[191]

Scaled-up generation and new distribution and transmission technology would be needed so this renewable electricity could be used.[192]

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada use its resources to prioritize support for identified, technologically viable decarbonization options, as well as scaled-up renewable electricity generation and new distribution and transmission technology.

Carbon Pricing

Tristan Goodman pointed out that a carbon offset market can help to address concerns related to competitiveness.[193] A predictable carbon price is important, he said, and urged the government to ensure certainty on this front. Craig Golinowski agreed that a predictable carbon price was critical.[194]

Dale Beugin suggested that carbon pricing and flexible regulations should be the backbone of a cost-effective federal policy that aimed to minimize costs to achieve deep emissions reductions. He added that complementary policies, such as support for research and development, can make carbon pricing work better, both at reducing GHG emissions, and at doing so in a cost-effective way.[195] Jerry DeMarco was also supportive of carbon pricing.

A few witnesses pointed out that large emitters are often paying the carbon price on only a fraction of their emissions, because of the system of performance standards that was intended to protect competitiveness. In their views, this can be considered a subsidy.[196] Justin Leroux commented that the justification for allowing them to pay less is to maintain international competitiveness, but said the amount they pay is too low, and that they should eventually pay the full amount.[197] Julia Levin said the problems with carbon pricing should be “fixed” so Canada has a carbon pricing system “that works.”[198]

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada continue to emphasize carbon pricing and flexible regulations as the core of its emissions reduction policy, in order to minimize the costs required to achieve significant emissions reductions.

Recommendation 16

That the Government of Canada should make public investments in projects that are complementary to carbon pricing and to other regulatory policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

International Competitiveness

Some witnesses raised questions about Canadian companies’ competitiveness as the country reduces GHG emissions and phases out subsidies and supports for the fossil fuel industry. Jerry DeMarco acknowledged that “[i]f one jurisdiction sticks its neck out and does something and the others don't follow, it could be put at a competitive disadvantage.”[199] However, he pointed out that this does not mean that failing to act to reduce climate change is the best course of action, and emphasized the importance of collaboration with other countries and actors:

It's a difficult issue with climate change, because you're never going to get a 100% consensus among nearly 200 countries on every measure and every definition […]

To the best extent, if we can at least collaborate with our G7 and G20 colleagues in looking at this in a coordinated way, which […] includes peer reviews with other nations, then we'll have a better chance of having the entire herd go in the same direction, rather than just one of us going ahead of the pack or behind the pack.[200]

Tristan Goodman stated his support for the Government of Canada’s goal of tackling emissions, but felt that the oil and gas industry needs support in order to deal with the costs of complying with government policies on climate change: He emphasized a need to “remain competitive with other nations and attract significant investment capital into this country”[201] and a desire to ensure that oil and gas development occurs in Canada while it is still needed.[202] Otherwise, he suggested, the production would take place in other jurisdictions that lack “climate expertise and ambition.”[203]

Ben Brunnen similarly argued:

Investing in emissions reduction technology is often unproven and can be substantially costly. From a private sector perspective, I think for all aspects of the economy we would be looking for [government support for] incremental costs that would be borne [by government] that would be difficult to support for investors, particularly investors who are looking at investing on a global basis. If we can't provide the returns to these investors, they'll simply invest in other jurisdictions or globally.[204]

Shannon Joseph, Vice-President, Government Relations and Indigenous Affairs at CAPP, added, “[i]t is that Canada is really beyond low-hanging fruit in terms of emissions reduction ambition. To go beyond that low-hanging fruit is going to require innovation by all sectors and an investment.”[205]

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip was skeptical of such statements, reminding the Committee that “the fossil fuel industry has spent decades promoting misinformation about the safety of their activities and products, and delaying any meaningful government action that would have the effect of reducing their profits.”[206]

Jerry DeMarco emphasized the government’s role in working with the sector:

Canada will need to work with the oil and gas sector, but it shouldn't be afraid to regulate as well. It's not an entirely voluntary relationship between government and industry. They work together, but it's up to Canada, which made the commitment to net zero, to meet it, and that will require a range of measures, from carbon pricing to regulation to working with industry on voluntary measures—the whole gamut.[207]

Dale Beugin concurred, suggesting that governments should “maximize scarce public dollars by making public investments complementary to carbon pricing and other regulatory policies, rather than financing company compliance with those measures.”[208]

Mark Agnew considered the Net-Zero Accelerator Initiative a helpful fund with a vital role to play. If oil and gas companies did not have access to such initiatives, he said, the transition towards net zero would be much more difficult.[209] Julia Levin, however, saw this fund as a potential source of subsidies to the oil and gas sector, and suggested it should have “strict climate conditions,” to ensure it doesn’t become a subsidy for the sector.[210]

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada continue to ensure that the competitiveness of Canada’s oil and gas sector is considered when it makes decisions related to climate change measures, and that it continue to collaborate with other jurisdictions to address issues of global competitiveness.

Selected Considerations

Several additional considerations arose during the study, including the following.

Affordability

A number of witnesses mentioned the importance of ensuring the affordability of energy, food, housing, and other basic needs in Canada.[211]

A few witnesses expressed concerns that the elimination of fossil fuel subsidies could make energy and other necessities unaffordable.[212] Tristan Goodman pointed out that high energy prices affect low-income Canadians the most, and expressed concern about “energy affordability for Canadians as well as, quite frankly, globally.”[213]

Others, like Larry Rousseau, wanted governments to find other ways to support Canadians who needed support with affordability.[214] Several witnesses emphasized the risks to Canadians and others around the world from the impacts of climate change, seeing these as a reason for Canada to take measures that reduce emissions urgently.[215] Julia Levin said:

We know that, to avoid catastrophic climate change, we must transition our economies off fossil fuels in the next decade. We have the solutions to build a clean energy future, and we know that the transition away from fossil fuels will bring far greater energy affordability, security and better jobs.[216]

Supports That Directly Benefit Indigenous Communities

Stephen Buffalo mentioned examples of subsidies that affect Indigenous communities, such as support for diesel generating stations or Indigenous Services Canada support for natural gas and diesel projects, and highlighted the importance of providing heat and electricity in Indigenous communities.[217]

All witnesses who referred to Indigenous communities agreed that access to energy was a priority.[218] None of the testimony or briefs advocated for removing these subsidies; witnesses did, however, provide nuanced views on the types of subsidies received, pointing out that it is important to invest in diversifying the energy sources for these communities,[219] adding that money spent on subsidies could compromise availability of federal funds for transition and for provision of services,[220] among other points.

Energy Security

Ben Brunnen suggested that removing fossil fuel subsidies or supports could affect global energy security,[221] and Craig Golinowski commented that “[i]f we are unable to supply a sufficient quantity of energy to the human population, we'll have famine, we'll have war and we'll have chaos.”[222] Heather Exner‑Pinot equated energy security to climate change: “I agree that climate is a very important issue and I agree that the energy crisis is a very important issue. I don't think we should ignore one at the expense of the other.”[223]