ENVI Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

SUPPORT FOR CLEAN TECHNOLOGIES IN CANADA TO REDUCE DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS

1. Introduction

On 26 April 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) adopted the following motion:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee undertake a study of clean technologies being researched, manufactured, and utilized in Canada to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and reduce harms to the environment; that the study also include how Canadian clean technologies can be used to reduce global emissions; that the study consist of no fewer than six meetings; and that the committee report its findings to the House.[1]

The Committee conducted its study over seven meetings between June and October 2022 and heard from 53 witnesses representing 39 organizations. The Committee also received 32 briefs. Witnesses included stakeholders from a variety of clean tech areas: entrepreneurs, business accelerators, researchers, industry associations, environmental advocacy groups, educators, and government. The Committee notes that developments in clean technology have continued since the last meeting of the study during which witnesses were heard. The Committee sincerely thanks all witnesses and authors of briefs for their contributions to this study.

2. The Clean Technology Sector in Canada: An Overview

The federal government provides the following definition of clean technology—often referred to as “clean tech.”

Clean technology is any process, product or service that reduces environmental impacts through:

- environmental protection activities that prevent, reduce or eliminate pollution or any other degradation of the environment;

- resource management activities that result in the more efficient use of natural resources, thus safeguarding against their depletion; or

- the use of goods that have been adapted to be significantly less energy or resource intensive than the industry standard.[2]

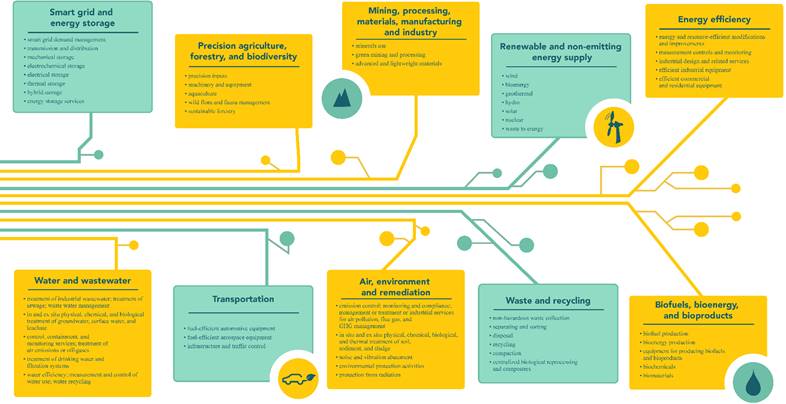

Figure 1 illustrates the areas that the federal government considers to be clean technologies.

Figure 1—Clean Technology Areas Recognized by the Government of Canada

Source: Government of Canada, Clean Technology Data Strategy.

The federal government classifies clean tech into six “Technology Readiness Levels”—based on a set of levels developed by the United States’ National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)[3]—as follows:

- research and development;

- pilot and demonstration;

- commercialization and market entry;

- growth and scale up;

- export; and

- clean technology adoption.[4]

Some additional terms used in the field of clean tech can be defined as follows:

- Biofuels are fuels derived from biomass, which “can take the form of a liquid such as ethanol or renewable diesel fuels, a gas such as biogas or syngas or a solid such as pellets or char.”[5]

- Decarbonization typically refers to the process of preventing and reducing the emission of greenhouse gases. It may include such actions as electrification, fuel-switching to low-carbon fuels, increasing energy efficiency, and capturing carbon.[6]

- Net zero emissions “means that anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere are balanced by anthropogenic removals of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere over a specified period.”[7]

- Non-emitting energy is energy generation which does not result in the emissions of greenhouse gases. Nuclear energy is considered non-emitting of greenhouse gases while in operation, although emissions are “associated with the mining, refining, and transportation of nuclear fuels and waste.”[8]

- Renewable energy is energy derived from renewable resources, or “energy derived from natural processes that are replenished at a rate that is equal to or faster than the rate at which they are consumed.”[9] It includes energy generated from solar, wind, geothermal, and water resources, as well as from some biofuels. Nuclear energy is not considered renewable because uranium is not a renewable resource.

Canadian exports of certain clean technologies have the potential to reduce GHG emissions in other parts of the world. Thus, the use of clean tech can contribute to Canadian and global efforts to reduce GHG emissions and limit global warming as per the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The importance of the use of clean technology in meeting Canada’s climate objectives—reducing emissions to 40%–45% below 2005 levels by 2030 and reaching net zero carbon emissions by 2050—was discussed by Vincent Ngan (Director General, Horizontal Policy, Engagement and Coordination, Climate Change Branch, Department of the Environment):

Reaching net zero will require significant effort to accelerate both the development and the deployment of clean tech. There is increasing global recognition that such technological transitions must be accelerated through ambitious action if the world is to avoid dangerous climate impacts. … [At the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow], over 40 countries, representing more than 70% of global GDP, committed to accelerating clean-tech innovation and deployment in line with transforming major sectors of the economy. This represents both an opportunity to drive down emissions and a chance to generate clean growth, with global clean-technology activity projected to reach $3.6 trillion by 2030.[10]

The federal government’s 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan, introduced on 29 March 2022, “committed to strengthening federal coordination on clean tech and climate innovation through a whole-of-government clean-tech and climate innovation strategy.”[11]

According to Andrew Noseworthy (Assistant Deputy Minister, Clean Technology and Clean Growth Branch, Department of Industry), Statistics Canada’s economic valuation of clean technology in Canada shows that, in 2020, clean tech contributed $26.8 billion to Canada’s GDP and provided over 200,000 well-paying jobs.[12] Between 2012 and 2020, clean tech employment grew by over 25% and the clean tech sector grew by 15%, faster than the Canadian economy’s overall growth (11%) during that same period.[13] Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta have high concentrations of clean tech companies.[14] As described by Mr. Noseworthy, “Canada has strength in a broad range of clean-tech areas, including clean energy and energy efficiency; hydrogen and low-emission transportation; batteries, smart grids and storage; carbon capture, utilization and storage; water and waste water; and agri-tech.”[15]

Drew Leyburne (Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Efficiency and Technology Sector, Department of Natural Resources), specified that “energy supply and use make up the single largest component of the clean-tech sector.”[16] Mr. Noseworthy noted that Canadian clean tech companies contribute to GHG emissions reductions not only in Canada but also internationally, as “the vast majority of Canadian clean-tech firms are focused on exports.”[17] In 2020, Canadian exports of clean tech were valued at $7.1 billion.[18]

Canadian Federal Government Support for Clean Technology

Andrew Noseworthy pointed out that, of the 13 Canadian companies on the 2022 Global Cleantech 100 list of high-performing and high-opportunity clean tech companies, all of them had “received support from the Government of Canada at some point in their development.”[19] Departmental officials highlighted a number of federal government funding initiatives and programs that support clean tech, including those listed in Table 1.

Table 1—Selected Federal Government Programs to Support Clean Technology

Program |

Responsible Entity |

Value and/or Year Initiated |

Purpose |

Net Zero Accelerator, part of the Strategic Innovation Fund |

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada |

Up to $8 billion |

Support large-scale, transformative and collaborative projects in industrial sectors to help meet Canada’s 2030 and 2050 emissions targets |

Industrial Research Assistance Programme |

National Research Council |

Ongoing for over 70 years |

Help small and medium-sized businesses build innovation capacity and take ideas to market |

Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy |

Natural Resources Canada |

$3.8 billion over eight years proposed through Budget 2022 |

Help create the critical minerals value chain in Canada for mining, processing, recycling and manufacturing of battery precursors |

Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program |

Natural Resources Canada |

$1.56 billion over eight years, as announced in Budget 2022 |

Support the construction phase of electrical grid modernization and renewable energy projects to decrease emissions and generate economic and social benefits |

Zero-Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Program and the federal incentive to purchase a zero-emissions vehicle |

Natural Resources Canada |

Total of $1 billion since 2016 |

Make electric vehicles more affordable and chargers more accessible |

Clean Fuels Fund |

Natural Resources Canada |

$1.5 billion |

Expand clean fuel production, distribution and use, including support for 10 new hydrogen production facilities as part of the Hydrogen Strategy for Canada |

Energy Innovation Program—Carbon capture, utilization and storage |

Natural Resources Canada |

$319 million over seven years through Budget 2021 |

Advance research, development and demonstrations of carbon capture utilization and storage technologies |

Sustainable Development Technology Canada’s Seed Funding, Start-up Funding and Scale-up Funding |

Sustainable Development Technology Canada |

Since 2002 |

Accelerate the progress of Canadian small and medium-sized companies developing, demonstrating and commercializing clean technologies |

Clean Technology Stream of the Impact Canada Initiative |

Natural Resources Canada |

$75 million starting in 2018 |

Run challenges to address barriers in clean tech development and adoption; includes the Indigenous Off‑Diesel Initiative |

Clean power and green infrastructure investments |

Canada Infrastructure Bank |

$2.5 billion allocated for clean power and $2 billion allocated for energy efficient retrofits over five years starting in 2022 |

Address funding gaps for projects in order to expand green infrastructure (e.g. building retrofits, charging and hydrogen refuelling stations) and clean power generation, distribution and use |

Agricultural Clean Technology Program |

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada |

$330 million announced in Budget 2022 |

Fund the development and adoption of clean technology to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Canada’s agriculture and agri-food sector |

Note: This list is not exhaustive of all initiatives of Budget 2022. The program information listed was accurate at the time of departmental officials’ testimony. Subsequent to this testimony, Budget 2023 was tabled and included additional clean tech programs and initiatives, including the Green Shipping Corridor Program ($165.4 million over seven years); $1.3 billion over six years to improve the efficiency of assessments of major projects like critical mineral mines and clean energy projects; and delivering the $15 billion Canada Growth Fund through the Public Sector Pension Investment Board to help de-risk private capital investment in clean technology projects (Government of Canada, Budget 2023).

Source: ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1115 (Marco Valicenti, Director General, Innovation Programs Directorate, Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food); ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1115 (Drew Leyburne); ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1125 (Drew Leyburne); ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1150 (Drew Leyburne); ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1155 (Kendal Hembroff, Director General, Clean Technology and Clean Growth Branch, Department of Industry); Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, News release, “Helping farmers and agri-businesses adopt clean technologies to reduce emissions and enhance competitiveness,” 4 June 2021; Natural Resources Canada, News Release, “Minister Wilkinson Releases Report on Public Charging Needs for Electric Vehicles in Canada,” 26 August 2022; Natural Resources Canada, Energy Innovation Program—Carbon capture, utilization and storage RD&D Call; Canada Infrastructure Bank, Infrastructure Partnerships; Sustainable Development Technology Canada, Annual Report Archive, Annual Report 2011, Annual Report 2022–2023; Government of Canada, Impact Canada, 2021–22 Annual Report; Canada Infrastructure Bank, Corporate Plan 2022–2023 to 2026–2027; Government of Canada, Net Zero Accelerator Initiative; Government of Canada, Smart Renewables and Electrification Pathways Program; Government of Canada, Clean Fuels Fund.

Since its launch in 2021, the agriculture clean-technology program, 110 projects, representing $33 million, have been announced.[20] Marco Valicenti (Director General, Innovation Programs Directorate, Department of Agriculture and Agri-Food), mentioned the following four technological areas of focus for future agriculture clean tech programs, noting that investments in these areas should result in “significant GHG reductions without negatively impacting yields:”

- nitrogen-reduction technologies;

- methane-reduction technologies;

- low-carbon energy systems; and

- emission-quantification technologies.[21]

In 2016, the federal government launched a clean tech data strategy, jointly led by Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED) and Statistics Canada, to improve its understanding of the scale of clean tech opportunities and the sector’s contribution to the Canadian economy.[22]

Over 90% of Canadian clean tech companies/firms are small and medium-sized enterprises.[23] Such firms may not have the resources necessary to navigate government bureaucracy and access supports such as those listed above. To address this issue, among others, the federal government launched the Clean Growth Hub (the Hub) in 2018. Co-led by NRCan and ISED, the Hub coordinates the 17 federal government departments and agencies[24] that support clean tech innovation. It “works as a ‘no wrong door’ approach for all clean-technology companies seeking to gain access”[25] to federal supports during any of the stages of clean tech innovation and adoption. Despite this intent, several stakeholders told the committee of the difficulty they experienced accessing government funding and getting their product/service to market (discussed later in the report).

The Hub has three core functions:

- “provide advisory services to clean technology proponents;”

- “enhance the coordination of Government of Canada supports and programming for clean technology;” and

- “strengthen federal capacity to track and report on results related to clean technology investment.”[26]

When asked by the Committee what percentage of projects funded reached the commercialization stage, the Hub responded:

While the Hub does not collect information on the number of projects that reach commercialization stage after receiving government funding, the Hub conducts an annual client satisfaction survey to capture results realized by clients following their engagement with the Hub. The survey found that 69% of clients referred to the Hub by government partners reported improved knowledge of government programs and 68% of program-ready clients are satisfied with the services provided by the Hub.[27]

NRCan conducted an evaluation of the Clean Growth Hub program and issued a report in 2021. Four recommended improvements to the program were made, all of which management at NRCan and ISED agreed to address starting in fiscal year 2022–23:

- enhancing outreach and communications to ensure its activities are tailored to client needs;

- strengthening inter-departmental collaboration to maximize client outcomes;

- updating the performance measurement data collected; and

- implementing an equity, diversity and inclusion strategy.[28]

3. The Role of Clean Technology in Addressing Climate Change

The Committee heard about the opportunities presented by clean technology to reduce emissions of GHGs, thus limiting the impacts of climate change. The following section explores the links between clean technology and addressing climate change, as discussed in witness testimony and briefs.

Clean Technology and the Energy ransition

Clean technology plays a significant role in the transition towards low-emissions sources of energy. The modelling annex to the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan shows that about half of the emissions reductions needed to meet Canada’s target are expected to come from “policies and measures incentivizing fuel switching to primarily electricity, greater use of biofuels and hydrogens, and the adoption of zero-emissions vehicles.”[29] Two witnesses pointed out that Canada has an advantage in a global low-carbon economy due to its low-carbon electricity supply.[30] Oliver James Sheldrick (Program Manager, Clean Economy, Clean Energy Canada) specified that Canada has one of the lowest-emitting electricity grids in the world, with 83% of its generation coming from non-emitting sources.[31]

Francis Bradley (President and Chief Executive Officer, Electricity Canada) remarked that, to reach its net zero targets, the federal government estimates that “Canada will need to produce two to three times as much clean electricity by 2050.”[32] Although this is a large increase, he noted that doubling Canada’s clean electricity production by 2050 breaks down to a 3–4% increase each year, which “is doable, except that we’re not doing it yet.”[33] Frédéric Côté (General Manager, Nergica) explained that the work of his applied research centre shows electricity as being “the energy of the future, and that the future of electricity is wind energy, solar energy and storage.”[34] Both Dr. Christina Hoicka (Canada Research Chair in Urban Planning for Climate Change, Associate Professor in Geography and Civil Engineering, University of Victoria) and Francis Bradley foresee electricity consumers/customers increasingly becoming producers in a more electrified future:[35]

To be able to meet those long-term targets that we have with respect to greenhouse gas emissions, we're going to have to significantly increase our grid-connected and grid-level power, but we're also going to have to massively ramp up what happens at the individual consumer level and at the community level. We're going to be seeing customers themselves increasingly becoming producers and part and parcel of this market. So we're going to see the grid itself expand, but we're also going to see the role of individual consumers and distributed energy resources and community-level resources expand.[36]

The research of Dr. Madeleine McPherson (Assistant Professor, University of Victoria) focuses on how to decarbonize energy systems. Her research team’s modelling shows that “the electrification of transport and heating systems is at the heart of decarbonization, but it will only work if … power systems are decarbonized first.”[37] Provinces largely powered by hydroelectricity (e.g. British Columbia, Manitoba, Quebec) are already decarbonized but, according to Dr. McPherson’s modelling, those provinces that still depend on fossil fuels for electricity generation will require wind and solar power installations “at a rate we’ve never seen before.”[38] Many provinces with fossil fuel-intensive grids also have excellent wind resources[39] and, while acknowledging the variability in wind and solar power generation, Dr. McPherson pointed out that “each of these future high-wind provinces conveniently neighbours a hydro-rich province.”[40] Therefore, if there were more interprovincial transmission linkages, “hydro in one province could balance the wind in its neighbouring province.”[41] Dr. McPherson sees a key role for the federal government in: 1) providing leadership and facilitating cooperation between provinces on interprovincial transmission; and 2) funding or de-risking private sector investments in interprovincial electrical transmission infrastructure.

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada, building on the Regional Energy and Resource Tables led by Natural Resources Canada, facilitate dialogue among provinces and territories in relation to interprovincial electricity transmission and recognize the important role of renewable energies in the adoption and deployment of clean technologies by prioritizing renewable and non-emitting energy sources to optimize the electricity grid.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada steer its investments and support programs to require that the effectiveness of technologies in reducing greenhouse gas emissions be demonstrated.

Ian Robertson (Chief Executive Officer, Greater Victoria Harbour Authority) outlined the improvements in air quality and the GHG emissions reductions that could result from having electric power available at the Victoria Cruise Terminal for large cruise ships to use instead of burning fuel while in port.[42] He noted that federal support had previously been available for deploying shore power, and emphasized the importance of further federal support to develop this capacity in Victoria.[43]

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada promote innovation and support the electrification of marine and aviation transport as a means of reducing emissions.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada support the development of shore power at Canadian ports as a means of reducing emissions from docked vessels.

A Multi-Pronged Approach to Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

In reflecting on the role of clean tech in reducing GHG emissions and thus addressing climate change, several witnesses noted the importance of applying multiple solutions to the challenge.[44] Frédéric Côté stated: “[t]he challenge we face is so big that a single solution will not be enough. All renewable energy sources need to be considered. The energy source best suited to the project can be chosen on the basis of [a] good impact study.”[45] Gabriel Durany (President and Chief Executive Officer, Association québécoise de la production d’énergie renouvelable [AQPER]) agreed:

[T]here's no single solution to meeting our climate targets, those of either Canada or Quebec. At AQPER, we encourage a rational modelling-based approach. Efforts to improve energy efficiency go hand in hand with efforts to increase renewable energy generation. These are complementary rather than contradictory notions.[46]

Vincent Moreau (Executive Vice-President, Écotech Québec) added:

Clean technologies are of course not the only solution to climate change. We also have to protect natural environments and change our consumption habits. It is clear though that we must adopt clean technologies. The important point here is that all actions or approaches are relevant and complementary, including the carbon price signal, incentives offered through programs to reduce the environmental footprint and fight climate change, and changes in consumption habits.[47]

As described by Stéphane Germain (President and Chief Executive Officer, GHGSat Inc.):

A whole-of-society approach is required in which Canada’s clean technology companies complement government efforts, enabling cost-effective and novel capabilities for reducing greenhouse gas emissions that would otherwise not be possible with either private or public sector solutions alone.[48]

Specific Examples of Clean Technology’s Potential to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Witnesses provided estimates of the potential GHG emissions reductions offered by specific types of clean technology. According to Lisa Stilborn (Vice-President, Public Affairs, Canadian Fuels Association), “low carbon fuels have the potential to cut transportation emissions in half by 2050.”[49] Randy Wright (President, Harbour Air Ltd.) expects GHG emissions for short flights by small aircraft to be reduced by 80% when his Harbour Air fleet is electrified.[50] Jasmin Raymond (Professor, Institut national de la recherche scientifique) explained that, based on her research on geothermal energy, geothermal systems, which use geothermal heat pumps to heat and cool buildings and generate electricity, can achieve energy savings of 60% to 70% over conventional home heating systems.[51] Based on his experience with European buildings, where energy intensity has been reduced by half in comparison to conventional buildings, André Rochette is confident that better integrative design[52] could reduce the energy consumption of Canadian buildings by 50% or more.[53]

Kleen Heat hydrogen gas heating units were estimated by Sam Soliman (Head, Engineering Services, Kleen HY-DRO-GEN Inc.) to have the potential to achieve emissions reductions of 6.4% of the 672-megatonne carbon dioxide equivalent target set by the federal government in 2020 in A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy: Canada’s Strengthened Climate Plan to Create Jobs and Support People, Communities and the Planet.[54] Doug MacDonald (Manufacturing Consultant, Kleen HY-DRO-GEN Inc.) suggested that Canada could be a leader distributing this technology globally,[55] potentially resulting in international GHG reductions. Darcy Spady (Managing Partner, Carbon Connect International Inc.) and Al Duerr (Partner, Carbon Connect International Inc.) discussed the potential of decreasing international GHG emissions through the sharing of Canada’s oil and gas methane reduction technical and regulatory expertise with other oil and gas producing nations.[56] The domestic and global methane emissions reduction potential stemming from Canadian research was also mentioned in briefs from the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and Alberta Innovates.[57]

In his testimony, Dr. Donald Smith (Distinguished James McGill Professor, McGill University) raised an important factor to consider when examining the relative impacts of soil carbon sequestration techniques: the length of time that carbon will be kept out of the atmosphere. He compared the addition of standard biomass to soils, in which carbon is captured in the soils for “years to decades,” with a clean technology innovation of adding biochar to soil, which keeps the carbon out of the atmosphere for “centuries to millennia.”[58] In this circumstance, the clean technology innovation would make soil carbon sequestration efforts to mitigate climate change effective over a much longer timeframe.

Likewise, Dr. Smith suggested that the length of time that carbon has been sequestered out of the atmosphere is a factor to consider when comparing biofuels made from crop residues to fossil fuels. He noted that burning biofuels releases CO2 “that came out of the atmosphere only a year or two before, whereas when you burn fossil fuels, the [CO2] that’s released came out of the atmosphere millions of years to hundreds of millions of years before.” In his view, the climate system is equilibrated to the absence of the CO2 that has been sequestered for millions of years.

For Dr. Kathryn Moran (President and Chief Executive Officer, Ocean Networks Canada) the use of negative emissions technologies, which remove carbon dioxide from the air and sequester it, is a necessity. She cited the United Nations Environment Programme and emerging scientific research, which indicate that emissions reductions alone will not be enough to avoid the climate tipping points that would lead to more severe climate change impacts.[59] As a result, she said, negative emissions technologies, such as ocean-based carbon dioxide removal, which her organization researches, must be developed and deployed.[60]

Which Technologies Can be Considered “Clean”?

The committee heard a number of views on whether certain technologies—for example, biomass, nuclear energy, hydrogen, and carbon capture utilization and storage (CCUS)—should be considered clean tech.

Nature Canada expressed concern about “the burning of wood for heat and energy, as a clean or low-carbon solution,” stating that claims about biomass from forestry being climate neutral are partially based on inaccurate accounting of emissions associated with its lifecycle and deployment. Nature Canada referenced analysis of government data it completed, along with the Natural Resources Defense Council, which found logging in Canada to be a high-emitting sector, with net emissions on par with oil sands operations.[61] Emmanuelle Rancourt (Coordinator and Co-spokesperson, Vision Biomasse Québec), however, supported the use of local abundant forest biomass as a replacement for fossil fuels. Ms. Rancourt emphasized the use of post-cutting, post-processing and post-consumption forest residues for direct heating (as opposed to co-generation of electricity and heat) to achieve the best GHG balance of the biomass as fuel.[62]

The testimony of John Gorman, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Nuclear Association, as well as several briefs received by the Committee, namely from Moltex Energy Canada Inc. and the Atlantic Clean Energy Alliance, emphasized the view that nuclear energy is a non-emitting energy source and should be prioritized in efforts to decarbonize energy systems.[63] These stakeholders viewed nuclear energy as a reliable source of baseload electricity to supplement intermittent renewable energy sources and to meet peak electricity demand. The testimony of Professor Christina Hoicka and authors of some other briefs, such as Ontario Clean Air Alliance and Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County and Area, cautioned against the use of nuclear energy, particularly small modular reactors, to reduce emissions.[64] Concerns raised about small modular reactors included their cost effectiveness, whether they would generate electricity in time to contribute to meeting Canada’s 2030 emissions reduction target, and the geo-political security considerations of importing their fuel.[65] The health and environmental risks posed by radioactive waste were also cited as concerns.[66]

In its brief promoting nuclear energy, the Atlantica Centre for Energy mentioned the application of life cycle assessments to compare various energy sources.[67] Drew Leyburne expanded on the concept of life cycle analyses as follows:

The real importance of life-cycle analysis when you're doing climate or other environmental modelling is that you can't just look at the end use [e.g. tailpipe emissions]. You have to look at the full lifespan, cradle to grave, where it came from. That applies whether you're talking about a critical mineral, a renewable resource or a fossil fuel. Specifically, on the critical minerals strategy, we are expecting, for example, a tenfold increase in the demand for rare earth elements by 2030 across the globe. An explicit part of the critical minerals strategy is to look at that full life cycle, including manufacturing and recycling applications, so that we can try to make this critical mineral economy more circular, as we say.[68]

4. Areas for Federal Government Action Related to Clean Technology

Witnesses presented many areas in which they felt that federal government action related to clean tech was needed. The following are examples of those areas.

Scaling Up Support for Market-Ready Technologies

The Committee heard that a number of clean technologies are fully ready to be deployed in Canada on a large scale—which could help the country achieve its GHG emissions reduction targets—but that they are not yet being deployed at this scale. Wind and solar energy generation technologies were cited by several witnesses as being ready to scale up immediately.[69] Dr. Christina Hoicka specified other existing and proven decarbonization technologies that could be deployed, namely “electrification of transportation, deep energy retrofits[70] to buildings, the rapid introduction of heat pumps and the rapid scale-up of waste heat capture for heating and cooling … in cities and industrial districts.”[71] Implementing these strategies requires quickly scaling up renewable electricity generation and implementing new distribution and transmission technologies.[72] However, Dr. Hoicka’s research reveals that “Canada is not supporting these proven technologies to the extent needed to reach our climate goals.”[73] Dr. Hoicka emphasized the importance of meeting our 2030 and 2050 targets in order to avoid the “far more disastrous [impacts of climate change] to current and future generations.”[74]

Dr. Brendan Haley (Director, Policy Research, Efficiency Canada) identified cold climate heat pumps as an energy efficient technology available now that should be scaled up.[75] André Rochette (Founder, Ecosystem) concurred:

If there's one area of technology in which Canada should be a leader, it's heat pumps. We live in a climate and environment in which electricity is affordable and clean… [and] most of the energy we consume is used for heating. Heat pumps are therefore the best technology for the future.[76]

In their testimony and brief to the Committee, representatives of Carbon Connect International Inc. discussed how Alberta’s long focus on methane emissions reduction have yielded “existing, proven technology that can be implemented quickly” and recommended continued federal government financial support for national methane emissions reductions.[77]

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada scale up its support to the deployment and uptake of proven technologies that would decarbonize the Canadian economy, and support provincial and territorial efforts to expand and modernize renewable electricity generation, distribution and transmission technologies, and employ clean technologies.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada accelerate efforts to employ clean technologies in the construction and retrofit of housing to substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Federal Funding and Clean Growth Hub Support

“It is good that many billions of dollars are available to drive the adoption of clean technologies. However, [the funding] also needs to be well directed and aligned. Also, we need to make sure there is proper accountability so that these programs and investments are actually contributing to protecting the environment and fighting climate change.”[78]

The Committee also heard various perspectives on the availability of and access to government funding for clean tech. Graeme Millen (Managing Director, Climate Technology and Sustainability, Canada Branch, Silicon Valley Bank) had a positive view of a number of the funding programs for clean tech:

One of the good things is that the federal government's already doing a pretty good job of leveraging private capital through programs like SDTC, IRAP, SR and ED [Scientific Research and Experimental Development], and SIF, for example. These are all fantastic programs, which are not only enabling the de-risking of some early stage technologies—which is being matched with private venture capital—but also attracting international capital into these companies.[79]

Some witnesses felt that support for early phases of clean tech development (e.g., research and development) was strong in Canada,[80] but that support for later phases was comparatively weak. Vincent Moreau cautioned that it is often difficult for entrepreneurs to find funding for the final phases of development, and suggested targeted funding to assist with approvals and certifications.[81] Frédéric Côté praised Canadian tech companies’ engineering and science abilities, but called for help on commercialization, stating “the move from idea to market needs to be better supported.”[82] He continued: “the challenge is so large that we need to bring all potential stakeholders together, whether it be renewable energy producers, inventors or entrepreneurs. … It would be good for everyone to sit down together.”[83] Swapan Kakumanu (Chief Financial Officer and Co‑Founder, Fogdog Energy Solutions Inc.) expressed a wish for more support for capital expenditures.[84]

Mr. Moreau recommended greater flexibility and adaptability in funding programs, particularly because the clean technology sector evolves so quickly. He also suggested that approval processes for funding be accelerated because waiting six to nine months to receive money is “too long for a small startup” that is trying to get funding and test a technology to get it to market as soon as possible.[85] Ivette Vera-Perez (President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association) appreciated government funding programs such as SIF and the Clean Fuels Fund as “great signals of the ambition the government has for Canadian clean-tech companies,” but also suggested that the resource-intensive application process and long wait times are a deterrent for project proponents.[86]

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada offer more flexibility and strive for faster approvals in its clean technology funding programs, including small-scale projects that have not reached widespread commercial scalability, namely by ensuring appropriate human and technical resources.

Vincent Moreau saw an opportunity for greater federal support to liaison organizations that “bring all the players together, whether it’s accelerators, financiers, venture capitalists, or companies, to better support them and establish more links.”[87] He noted that as the clean energy transition progresses, changes will happen faster, and liaison organizations will be even more important. Dr. Brendan Haley saw an opportunity for the federal government to provide strategic leadership in the field of deep building retrofits—extensive overhauls that reduce energy consumption dramatically. He sees a need for greater coordination so that federal and provincial incentives for deep building retrofits can be effectively combined, and also sees a need for federal energy efficiency programs that are accessible to low-income Canadians.[88] He asserted that buildings should be retrofitted together, not one at a time, in order for retrofits to reshape demand for related Canadian goods and services:

By aggregating a bunch of those buildings together, you all of a sudden have reshaped the nature of demand to open up a negotiation with manufacturers and other solution providers in your market to say, “If we can deliver all this demand, you can now have that certainty to change your manufacturing process, to perhaps manufacture certain types of products in Canada that aren't done now or to come up with solutions that nobody has thought about before to solve the problems we have.” Matching that supply and demand is really where we need to go.[89]

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada coordinate energy retrofit programs with provincial programs to facilitate access to Canadians, and work toward developing or supporting energy retrofit programs that are accessible to people with low incomes.

When asked what type of federal support would be most useful, Dr. Donald Smith described situations where his research findings progressed to technologies and products but commented that there was a barrier to commercialization. If such a technology never reaches a market and is never adopted, its environmental benefits are never realized. Consequently, he suggested it would be helpful if there were advisers that innovators could speak to “because each situation can be quite unique.”[90]

Supporting Decision-Making with Data and Modelling

In order to support decision-making on clean tech investments, a number of witnesses described the importance of developing further supports for robust data and modelling. Gabriel Durany highlighted that the potential and viability of wind energy was illustrated by techno-economic modelling commissioned by the Quebec government, which encouraged AQPER to focus on promoting wind energy.[91] Dr. McPherson spoke positively of the almost five million dollars dedicated by NRCan to an energy modelling hub, which could bring together modellers and decision-makers for an evidence-based conversation evaluating different energy pathways.[92] She saw this as partially addressing a large gap for Canada, in comparison to the United States (U.S.) and Europe, in linking energy modellers to decision-makers.[93] Emmanuelle Rancourt discussed the importance of, for example, consulting data on environmental conditions before making decisions about the use of forest industry residue (e.g. woody debris left after logging or timber processing) for biomass energy generation. Ms. Rancourt explained that soil vulnerability (e.g., soil porosity, slope) in the area of potential residue harvesting should be taken into account, to ensure that enough forest residue is left to enrich the soil and promote ecosystem regeneration. Vision Biomasse Quebec would appreciate greater availability of such data, perhaps as part of a framework for decision-making.[94] Jeanette Jackson (Chief Executive Officer, Foresight Cleantech Accelerator Centre) recommended that the federal government develop an “energy decision tree” to map out which low carbon energy sources make the most sense (e.g., hydro, biofuels, hydrogen) based on different regions’ economic drivers and waste energy materials.[95] Witnesses also recommended tying incentives and supports to measured GHG emissions reductions and/or the number of clean tech jobs created.[96]

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada make more of its support to clean technology contingent on greenhouse gas emissions reductions achieved and on the number of clean technology jobs created, particularly good paying union jobs.

Taking a Strategic Approach

Some witnesses felt that the Government of Canada should develop a national strategic approach that would shape clean technology advancement. John Gorman (President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Nuclear Association) emphasized that Canada should “urgently require the development of a clear clean energy industrial strategy” that would include all clean energy technologies that do not emit GHGs.[97] Frédéric Côté suggested “a national industrial policy to govern the extraction of raw materials to deployment, in order to have greater influence and reach in international markets.”[98] Francis Bradley thought it would be valuable for Canada to develop a national strategy specifically for electrification.[99] Daniel Breton (President and Chief Executive Officer, Electric Mobility Canada) acknowledged Canada’s existing Critical Minerals Strategy but thought that it should advance much faster than it is currently.[100] He also stressed the importance of having an integrated critical mineral strategy, covering mining and refining, mineral transformation, battery manufacturing and EV assembly, in order to create the most Canadian jobs.[101]

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada integrate its support for clean technology within all existing federal strategies, such as the Critical Minerals Strategy, the National Housing Strategy and the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership, prioritizing the objectives of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and fostering the development of sustainable jobs.

Federal Government Procurement

André Rochette saw an opportunity for the Government of Canada to deploy more innovation and creativity in clean tech by changing its approach to procurement. Mr. Rochette suggested that projects for federal government energy efficiency projects are often carried out based on a cost recovery formula, and “unfortunately, no exceptional results will be achieved if we constantly focus on project costs rather than results.”[102] Instead of being prescriptive in requests for tender, and focusing primarily on cost (input) when awarding contracts, Mr. Rochette suggested following a model used by NASA, which focusses on a project’s desired results (output). He explained that NASA changed to an outcome-based procurement and contracting process 20 years ago and that they have “achieved a great cost reduction” while reaching “greater goals.”[103] Outcome-based procurement and contracting tell the market what problem needs to be solved and asks the vendor to come up with a creative solution, rather than dictating the specifications of the expected solution to a problem in the request for tender.[104]

When speaking about barriers to the adoption of some clean technologies, Jeanette Jackson warned that if requests for tender are too prescriptive, an innovation like low carbon concrete might not be selected, even if it could perform as well as the conventional alternative at a comparable cost.[105] Ms. Jackson suggested that contracting entities such as municipalities could be made more aware of how to enable more clean tech innovations through their requests for tender. Natalie Giglio (Senior Associate, Business Development, Carbon Upcycling Technologies Inc.), whose firm captures point-source carbon dioxide (CO2) and includes it in cement replacements, strongly supported performance-based procurement:

What I would suggest is changing the specification language to be about performance, and not a prescriptive mix where you say you need to have this many kilograms of cement and this many kilograms of aggregate and sand. We want it to be performance-based, to say, “Use whatever ingredients you need to make this strength of concrete.” That's going to be what allows innovations like ours to be included in procurement and infrastructure that the government funds.[106]

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada pilot outcome-based procurement and contracting, with greater flexibility in its requests for tender, in order to encourage innovative solutions, the adoption of clean technologies, and greater greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

Witnesses commented that the Government of Canada could support clean technologies in demonstration and commercialization phases by procuring those technologies itself.[107] Such procurement could help to prove and demonstrate these technologies and de-risk their subsequent adoption by others. For example, Doug MacDonald, of Kleen HY-DRO-GEN Inc., hoped that the government “could lead the charge by demonstrating huge cost savings” if it deployed his company’s hydrogen gas heater.[108] The discussion of federal procurement extended to outer space, from which commercial satellite remote sensing companies can measure GHG emissions in Canada and globally. Stéphane Germain (President and Chief Executive Officer, GHGSat Inc.) stated that Canadian commercial satellite remote sensing companies call on the Government of Canada to be an “anchor tenant” and to make “ongoing bulk procurements of earth observation data and analytics,” as is common practice for NASA and the European Space Agency. According to this witness, while supporting Canadian remote sensing clean tech companies, this would also respect the Government of Canada’s own Space-Based Observation Strategy which calls for using satellites to measure key environmental and health indicators (such as GHG emissions).[109]

Oliver James Sheldrick suggested that the Government of Canada could leverage spending that would take place anyway, such as on infrastructure, to build out markets for “cleaner steel and cleaner cement” through a “buy clean” policy. He noted that “clean” procurement is estimated to increase overall project costs by no more than 1–2%.[110] He commented that the government’s substantial buying power has the potential to create and expand markets, thereby encouraging private sector adoption of clean technologies.[111] Dr. Kathryn Moran suggested that the federal government follow the lead of the U.S. by supporting clean technology through procurement:

In the U.S., when there is a high-risk, high-reward technology that needs to be developed, the first tool they use is government procurement. They buy it first and get it funded, and that moves it further to have, then, investments from venture capitalists going forward. Let's use our procurement tool and get some of these technologies going.[112]

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada enhance its Greening Government Strategy by adopting the following priorities that will enable it to play a leading role for the widespread deployment of clean technologies:

- be an early and important customer for clean technology innovations; and

- plan and execute deep energy retrofits of its real estate portfolio as soon as possible.

Providing the Best Regulatory Environment for Clean Technology

“Regulatory certainty is absolutely primordial for us. Investment decisions are not made on one- or two-year cycles, they’re made on 10-, 20- or 25-year cycles.”[113]

Jean Létourneau (Vice-President, Community Solar and Strategic Initiatives, Kruger Energy Inc.) highlighted predictability and stability in the regulatory environment as keys to the success of renewable energy projects.[114] In their brief, Next Hydrogen expressed the importance of regulatory certainty and continued implementation of carbon pricing and the Clean Fuel Regulations to incentivize investments in green hydrogen.[115] The importance of carbon pricing and regulatory certainty was also described by Stéphane Germain:

Pricing mechanisms have been an incentive that has helped many clean-tech companies build financial models and business models that allow them to demonstrate to investors that there will be a return on investment for their venture capital investments. That's certainly true in our case. We demonstrate that when there's a price on carbon, it motivates our customers to better understand, control and ultimately reduce their emissions.[116]

Craig Golinowski (President and Managing Partner, Carbon Infrastructure Partners Corp.) also emphasized the importance of certainty on carbon prices, noting that the risk of a future government eliminating the carbon price can make it difficult for companies to secure the large-scale investments they need for carbon capture and storage projects.[117]

Daniel Breton discussed the benefits of regulation for the adoption of EVs. He noted that 15 U.S. states, Québec, British Columbia, Europe and China have net-zero emission standards, and that those are the jurisdictions to which electric vehicle manufacturers prioritize shipping their vehicles for sale. He suggested that a net-zero emissions vehicle standard, guaranteeing that Canada will meet its EV sales targets, would establish market predictability and attract an array of EV-related industries to Canada.[118]

To encourage agricultural clean tech innovations, Robert Saik (Founder and Chief Executive Officer, AGvisorPRO Inc.) advised against regulation, and against “punitive”[119] policies against farmers. Instead, he suggested incentivizing innovations and recognizing those already being implemented by farmers.[120]

Various witnesses discussed the need to speed up regulatory approvals—sometimes referred to as “permitting reform”—for clean energy projects. Randy Wright shared his experience getting an electric plane certified. He found the certification process with Transport Canada very slow, with a lack of departmental resources and expertise making it difficult to get the aircraft inspected. In contrast, it appears to him that the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration has a dedicated team for electrified aircraft and is “way ahead of Canada on these projects.”[121] Francis Bradley saw a role for the federal government in decreasing the time it takes to move clean energy projects through the approval process because currently, he said, a project takes a decade or more to move forward, but to meet the country’s net-zero commitments the pace must be accelerated.[122] He suggested the possibility of fast-tracking the best projects.

Mr. Moreau lamented that, in his opinion, the Canadian regulatory and fiscal environments make it easier to do business outside of Canada rather than within it. He observed that the Canadian government could make regulatory improvements that would make it easier to “implement our clean technologies at home.”[123] Zsombor Burany (Chief Executive Officer, BioSphere Recovery Technologies Inc.) pointed out that funding for scaling up a small or medium enterprise is difficult to find in Canada.[124] Jeanette Jackson recommended more flexibility, suggesting “innovation sandboxes[125] where regulatory and even capital structures to finance these types of projects are given a little bit more leniency.”[126]

Steve Barrett (Chief Executive Officer, eDNAtec Inc.) urged more flexibility in the government’s approach to environmental research and monitoring, where he has observed aversion to trying new methods. As he described, although his firm’s technology for measuring DNA in environmental samples is less expensive, more sensitive, and faster at identifying biodiversity than conventional sampling methods (e.g., physically catching and counting fish), there is resistance to change.[127] Christopher Morgan (Chief Executive Officer of Hoverlink Ontario Inc.) also encountered what he saw as resistance to change within government, as well as communication barriers and silos between different levels of governments and departments.[128]

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada improve the regulatory framework by examining the best methods to optimize review and approvals processes of low emissions energy projects and clean technologies, as well as improving access to markets for proven clean technologies in order to help meet Canada’s 2030 and 2050 greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets.

Responding to Changes in the United States’ Support for Clean Technology

The U.S. has recently committed substantial investments to support its goal of being the global leader in clean energy technology, manufacturing, and innovation.[129] In November 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act[130] was signed into law, authorizing approximately US$550 billion in new spending over five years in areas such as electricity infrastructure, roads and bridges, public transit, and electric vehicle chargers.[131] This was followed, in August 2022, by the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA),[132] which aimed to confront “the existential threat of the climate crisis” while accelerating clean energy production, lowering energy costs, and creating new economic opportunities for workers.[133] The IRA contains a broad array of clean energy tax incentives, grants and loan programs totaling approximately US$370 billion over ten years. This includes, for example, clean energy production and investment tax credits, US$40 billion of loan authority for innovative clean energy projects, and US$27 billion for competitive grants in clean energy and climate projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Substantial U.S. government support for clean energy technology presents both challenges and opportunities for the Canadian economy. In their testimony to the Committee, several witnesses expressed the concern that, without comparable programs and incentives in Canada, Canadian industries and workers will be left behind.[134] In the context of auto manufacturing, Brian Kingston (President and Chief Executive Officer at the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers' Association) noted that Canada’s current zero-emissions manufacturing tax credit is much narrower than the IRA’s advanced manufacturing production credit, which provides companies that build battery cells or modules in the U.S. with a refundable credit of $35 per kilowatt hour. He warned that “if we don't match what the U.S. has done … it's highly unlikely we will see significant battery investments made in Canada going forward.”[135] Nevertheless, Mr. Kingston explained that the IRA also presents unique opportunities for Canada, noting that it incentivizes the sourcing of critical minerals within North America. He suggested that Canada should leverage its competitive advantages in niche areas to ensure that Canada remains part of the U.S. supply chain.[136]

Similarly, several other witnesses emphasized the need for Canada to keep pace with U.S. biofuel and hydrogen incentives.[137] For example, Lisa Stilborn explained that the IRA accelerated long-standing support for the U.S. biofuels industry, which is in direct competition with the Canadian biofuels industry due to the integration of the North American fuel market. She argued that comparable Canadian incentives are needed to level the playing field, specifically a 10-year low-carbon fuel production tax credit.[138] Ian Thomson (President, Advanced Biofuels Canada) proposed additional Canadian measures that could mirror IRA incentives, including a refundable low-carbon fuel production tax credit, a full exemption of low-carbon-intensity fuels from the fuel charge under the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act, conversion of the proposed federal CCUS tax credit to a production tax credit with similar rates to those in the IRA, and an amendment of the zero-emission technology manufacturing tax cut to apply to all low-carbon-intensity fuel manufacturing registered under the Clean Fuel Regulations.[139]

In the context of clean hydrogen, Zsombor Burany emphasized that, in order to keep pace with the U.S., the Canada Infrastructure Bank should be able to fund a higher percentage of project costs and provide loans at no interest for 20-year periods.[140] Moreover, Bruno G. Pollet (Deputy Director and Director, Green Hydrogen Laboratory, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Institute for Hydrogen Research) highlighted the risk that U.S. incentives would result in a loss of skilled labour from Canada to the U.S.. He noted that this is of particular concern in the hydrogen sector, where there is already a shortage of skilled workers.[141]

Craig Golinowski explained that the IRA provides companies with a tax credit that effectively provides 12 years of certainty as to how much can be earned for each tonne of CO2 that is captured and sequestered. In comparison, the Canadian incentive framework for CCUS technologies is less certain, due to the possibility of changes to carbon pricing that would affect operating costs and return on capital. He suggested that the Government of Canada enter into “contracts for differences” with CCUS developers “so that, if the carbon price is changed by a subsequent government, the contract would state that any differences would be compensated for by the government if the carbon price ended up being changed to a lower number.”[142] Federal government carbon contracts for differences were also viewed favourably by Electricity Canada members, as such contracts could provide stability and certainty regardless of future government policy changes.[143]

The Government of Canada has proposed certain measures in response to the IRA. These include an investment tax credit of approximately 40% for clean hydrogen, and 30% for investments in electricity generation systems, stationary electricity storage systems, low-carbon heat equipment, industrial zero-emission vehicles and related charging or refueling equipment.[144] Nevertheless, further action is needed to ensure the continued global competitiveness of Canadian clean technology. Numerous authors of briefs and witnesses suggested that Canada review its support for various clean technology sectors to identify gaps in incentives, funding, and regulations that could give other countries, particularly the U.S., a competitive advantage, and that it take action to close those gaps.[145]

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada conduct a gap analysis of the incentives in place for clean technology in Canada and the United States, to study differences and understand policy gaps within the specific regional and national context to inform future policy decisions.

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada enter into contracts for differences to provide greater certainty with respect to scheduled increases to carbon pricing.

5. The Energy Transition: Workers, Jobs, and Clean Technology

“Clean technology is crucial for the future, but the person who built the first automobile rode a horse and buggy to work, so we need to make sure we keep [current workers] in mind and we allow them to help guide how we move forward as well.”[146]

Information provided by NRCan indicated that there were approximately 210,000 direct jobs in the clean tech sector in Canada in 2020, and that these jobs paid an average of $80,834, which was higher than the Canadian economy-wide average annual salary of $68,678; however, women in the clean tech sector in 2020 earned 82% of what men earned.[147] By comparison, there were 178,500 jobs in the oil and gas sector in that year.[148] Table 2 presents the direct clean tech jobs in 2020 (the last year for which data were available at the time of witness testimony) in Canada by industry. Table 3 presents the regional distribution of those jobs across Canada.

Table 2—Direct Clean Technology Jobs in Canada, by Industry, 2020

Industry |

Direct Clean Technology Jobs |

Percentage of Total Clean Technology Jobs |

Engineering and construction |

68,392 |

33% |

Professional, scientific and technical services |

49,451 |

24% |

Manufacturing |

37,376 |

18% |

Administrative and support |

2,042 |

1% |

Other industries |

52,976 |

25% |

Total |

210,237 |

100% |

Note: Due to rounding, percentages may not equal 100%.

Source: Extracted from Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0632-01 Environmental and Clean Technology Products Economic Account, Employment, as cited in Innovation, Science and Economy Development Canada, Written Response to Questions from ENVI, 7 June 2022.

Table 3 —Regional Distribution of Clean Technology Jobs in Canada, by Industry in 2020.

Province / Territory |

Engineering construction |

Professional, scientific and technical services |

Manufacturing |

Administrative and support |

Other industries |

Total clean tech employment all industries |

Newfoundland and Labrador |

7,010 |

247 |

65 |

NA |

521 |

7,848 |

Prince Edward Island |

248 |

192 |

54 |

10 |

406 |

910 |

Nova Scotia |

3,873 |

1,530 |

810 |

32 |

1,178 |

7,423 |

New Brunswick |

789 |

437 |

665 |

101 |

989 |

2,981 |

Quebec |

18,054 |

12,131 |

10,883 |

426 |

9,159 |

50,653 |

Ontario |

14,446 |

20,687 |

16,363 |

1,033 |

24,739 |

77,268 |

Manitoba |

4,999 |

890 |

1,259 |

63 |

1,643 |

8,854 |

Saskatchewan |

2,840 |

1,047 |

816 |

62 |

1,783 |

6,548 |

Alberta |

8,693 |

5,522 |

1,646 |

107 |

5,695 |

21,663 |

British Columbia |

7,381 |

6,615 |

4,814 |

197 |

6,694 |

25,701 |

Yukon |

16 |

84 |

NA |

24 |

34 |

158 |

Northwest Territories |

29 |

48 |

NA |

NA |

72 |

151 |

Nunavut |

15 |

22 |

NA |

NA |

64 |

106 |

Canada |

68,392 |

49,451 |

37,376 |

2,042 |

52,976 |

210,237 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Environmental and Clean Technology Products Economic Account: Human Resource Module, 2020, as cited in Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, Written Response to Questions from ENVI, 7 June 2022.

In order for Canadian workers to take full advantage of clean technology opportunities, and to ensure there are enough skilled workers available to implement clean technologies, witnesses from a variety of sectors emphasized the need for technical training and applied research through colleges and polytechnics.[149] For example, Camille Lambert-Chan (Director, Regulation and Public Policy, Propulsion Québec) emphasized the need for technical training when she identified labour as the most important issue for growth of member businesses of Propulsion Quebec:

The workforce issue is important because we're talking about a transition and training programs that often don't exist, either at vocational training centres, universities or CÉGEPs. A lot of the focus is on engineering training, but it's also important to keep in mind the technical component behind that.[150]

Dr. Brendan Haley identified a need in Canada for more training and people entering trades to support building energy retrofits.[151] Daniel Breton identified the lack of new qualified workers throughout the EV battery supply chain as a roadblock to EV expansion in Canada, stating, “[w]e need to make that transition for workers who work in industries in decline to come and work in the electric mobility sector.”[152] Luisa Da Silva (Executive Director, Iron and Earth) cautioned that Canada “runs the very real risk of a clean energy skills drain” if employment opportunities aren’t created within Canada for existing skilled energy workers.[153]

Recommendation 16

That the Government of Canada collaborate with provinces and territories to invest more in skills training, including skills upgrading and requalification programs, in order to ensure that:

- Canada has a workforce that is skilled and available to meet the labour needs that will be created by the deployment of clean technologies;

- strategies and programs related to the introduction of clean technologies clearly value professional requalification and upgrading skills of workers in transforming sectors; and

- pay equity is attained by supporting women in the clean technology sector.

6. Clean Technology in Northern, Remote, and Indigenous Communities

A benefit of clean technology is that some types could help enable energy independence for northern and remote communities—including many Indigenous communities—that rely on diesel for electricity generation. For such communities, which are not connected to an electricity grid, diesel provides a year-round reliable and secure source of power and heat. However, diesel must be shipped from the south, making it expensive, and its combustion results in air pollution including GHGs. Francis Bradley described a “disproportionate” amount of non-renewable energy generation currently required in rural and remote communities,[154] while Frédéric Côté added that “close to 200,000 people in Canada use diesel to generate their electricity in off-grid systems.”[155]

As one possible solution, Jasmin Raymond suggested geothermal energy for local clean energy generation in the North.[156] Emmanuelle Rancourt believed that northern communities that are not connected to the hydroelectricity grid and rely heavily on fossil fuels could, in many cases, benefit from switching their fuel source to wood pellets, although not necessarily in the far North.[157] Where possible, local residual forest biomass should be used, she said.[158] Luisa Da Silva suggested solar and wind energy as proven technologies that could be implemented in communities that are currently dependent on diesel. Ms. Da Silva views support for energy sovereignty, which Indigenous communities could gain through local renewable energy generation, as a part of reconciliation.[159]

Frédéric Côté, who is involved in an energy transition project in Inuit communities, advised that northern renewable energy projects should include training of local residents so they may operate and maintain the systems. To accomplish this, funding for travel expenses is needed as part of such energy projects, either for community members to travel to educational institutions or for trainers to travel to the North. Mr. Côté added that “[i]t’s necessary to go out into communities and engage with [community members] if they are to properly take over projects.”[160] Although he had some remote connectivity challenges, Dr. Michael Ross (Industrial Research Chair in Northern Energy Innovation, Yukon University) was able to provide some testimony. He highlighted the importance of considering many aspects when integrating renewable energy into remote communities to displace some diesel energy generation. He applies the “STEEP” framework to his projects, representing considerations of a Social, Technical, Economic, Environmental and Policy nature.[161] The Committee emphasizes that energy transition projects in Indigenous communities should be Indigenous led.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada accelerate its support for Indigenous, northern and isolated communities in their transition from diesel to local clean electricity production, with priority given to renewable sources.

7. Conclusion

The Committee heard from witnesses with various roles in the clean tech sector in Canada: innovators, scientists, entrepreneurs, business incubators, academics, and more. Witnesses suggested ways in which the federal government could strengthen its supports to clean tech, emphasizing particular need for support in the later phases of technology development: demonstration, early adoption, and commercialization. Better support during these later phases should help promising innovations bridge the gap between research and development and market success. It was made clear that Canadian clean tech growth stands to benefit the economy and workers through the creation of well-paying skilled jobs, including some to which workers in declining industries could transition.

Witnesses agreed that the sector has the potential to support the reduction of GHG emissions in Canada—and emissions reductions could happen internationally when Canadian clean technology is exported. By reducing GHG emissions, clean tech can help limit the negative impacts of climate change. However, in order for emissions reductions to happen fast enough to meet Canada’s targets, existing clean tech has to be scaled up faster, new technologies must be developed sooner, and clean tech must be just one among many solutions that are implemented.

[1] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (ENVI), Minutes of Proceedings, Meeting 13, 1st Session, 44th Parliament, 26 April 2022.

[2] Government of Canada, About the Clean Growth Hub.

[3] ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1245 (Andrew Noseworthy, Assistant Deputy Minister, Clean Technology and Clean Growth Branch, Department of Industry); National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Technology Readiness Levels Demystified, 10 August 2010.

[4] Government of Canada, Federal ecosystem of support for clean technology.

[6] Environment and Climate Change Canada, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy: Canada’s strengthened climate plan to create jobs and support people, communities and the planet, 2020.

[7] Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, S.C. 2021, c. 22, s. 2.

[8] Canada Energy Regulator, Canada’s Renewable Power- Canada.

[9] Government of Canada, About Renewable Energy.

[10] ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1110 (Vincent Ngan, Director General, Horizontal Policy, Engagement and Coordination, Climate Change Branch, Department of the Environment).

This figure is cited in the Smart Prosperity Institute’s 2018 discussion paper, Canada’s Next Edge: Why Clean Innovation is Critical to Canada’s Economy and How We Get it Right: “McKinsey estimates that resource-based sectors stand to benefit from a $3.6 trillion investment in boosting resource efficiency and innovation worldwide by 2030.” (p. 21). Smart Prosperity’s source for this figure is Dobbs, Oppenheim, Thompson, Brinkman and Zornes, McKinsey & Company, Resource Revolution: Meeting the world’s energy, materials, food, and water needs, 2011.

Another estimate of the future economic opportunity presented by clean technology is provided by the International Energy Agency’s Energy Technology Perspectives 2023: “the global market for key mass-manufactured clean energy technologies will be worth around USD 650 billion a year by 2030.”

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1115 (Drew Leyburne, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Efficiency and Technology Sector, Department of Natural Resources).

The 13 Canadian companies on the 2022 Global Cleantech 100 list were: Carbicrete, Carbon Engineering, CarbonCure Technologies, Effenco, Ekona Power, E-Zinc, General Fusion, GHGSat, Ionomr Innovations, Minesense Technologies, Opus One Solutions, Pani Energy, and Svante (Natural Resources Canada, Statement by Minister Wilkinson Congratulating Canadian Clean Technology Companies, 13 January 2022).

[18] Ibid.

Statistics Canada data shows that exports of environmental and clean technology goods and services were just over $7 billion in 2020 (Statistics Canada, The Daily, Annual Survey of Environmental Goods and Services, 2020, 23 March 2022).

[21] Ibid.

[22] ENVI, Evidence, 7 June 2022, 1115 (Drew Leyburne); Government of Canada, Clean Technology Data Strategy.

[24] The 17 federal departments and agencies are : Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; Business Development Bank of Canada; Canadian Commercial Corporation; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada; Environment and Climate Change Canada; Export Development Canada; Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Global Affairs Canada; Indigenous Services Canada; Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (co-chair); National Research Council Canada; Natural Resources Canada (co-chair); Standards Council of Canada; Sustainable Development Technology Canada; Transport Canada; Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat; and Employment and Social Development Canada.

[26] Natural Resources Canada, Evaluation of the Clean Growth Hub Program, 5 May 2021.

[27] Innovation, Science and Economy Development Canada, Written Response to Questions from ENVI, 7 June 2022.

[28] Natural Resources Canada, Evaluation of the Clean Growth Hub Program, 5 May 2021. The 2022–23 Departmental Results Reports for Natural Resources Canada and for Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada may report on progress in addressing the recommendations of the evaluation. These reports were not yet available at the time of writing.

[30] ENVI, Evidence, 4 October 2022, 1615 (Dr. Madeleine McPherson, Assistant Professor, University of Victoria); ENVI, Evidence, 18 October 2022, 1555 (Oliver James Sheldrick, Program Manager, Clean Economy, Clean Energy Canada).

[32] ENVI, Evidence, 20 September 2022, 1645 (Francis Bradley, President and Chief Executive Officer, Electricity Canada).

[35] ENVI, Evidence, 20 September 2022, 1720 (Francis Bradley); ENVI, Evidence, 20 September 2022, 1715 (Dr. Christina Hoicka, Canada Research Chair in Urban Planning for Climate Change, Associate Professor in Geography and Civil Engineering, University of Victoria).

[38] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] ENVI, Evidence, 21 October 2022, 1310 (Ian Robertson, Chief Executive Officer, Greater Victoria Harbour Authority).

[43] ENVI, Evidence, 21 October 2022, 1335 (Ian Robertson). Subsequent to this testimony, Budget 2023 proposed “to provide $165.4 million over seven years, starting in 2023–24, to Transport Canada to establish a Green Shipping Corridor Program” intended to, among other things, invest in shore power technology (Government of Canada, Budget 2023, p. 135).

[44] ENVI, Evidence, 20 September 2022, 1620 (Vincent Moreau, Executive Vice-President, Écotech Québec); ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1300 (Gabriel Durany, President and Chief Executive Officer, Association québécoise de la production d’énergie renouvelable); ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1310 (Stéphane Germain, President and Chief Executive Officer, GHGSat Inc.); ENVI, Evidence, 27 September 2022, 1605 (Frédéric Côté).

[49] ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1405 (Lisa Stilborn, Vice-President, Public Affairs, Canadian Fuels Association).

[51] ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1415 (Jasmin Raymond, Professor, Institut national de la recherche scientifique).

[52] An integrated design process, “is a method for realizing high performance buildings that contribute to sustainable communities. It is a collaborative process that:

· focuses on the design, construction, operation and occupancy of a building over its complete life-cycle;

· is designed to allow the client and other stakeholders to develop and realize clearly defined and challenging functional, environmental and economic goals and objectives;

· includes a multi-disciplinary design team that includes or acquires the skills required to address all design issues flowing from the objectives; and

· proceeds from whole building system strategies working through increasing levels of specificity so as to realize more optimally integrated solutions.”

(Public Services and Procurement Canada, Integrated Design Process.)

[54] ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1415 (Sam Soliman, Head, Engineering Services, Kleen HY-DRO-GEN Inc.).

[55] ENVI, Evidence, 23 September 2022, 1430 (Doug MacDonald, Manufacturing Consultant, Kleen HY-DRO-GEN Inc.).

[56] Carbon Connect International Inc., Written Submission to ENVI, November 2022.

[57] Alberta Innovates, Written Submission to ENVI, October 2022; Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Written Submissions to ENVI, November 2022.

[58] ENVI, Evidence, 4 October 2022, 1655 (Dr. Donald L. Smith, Distinguished James McGill Professor, McGill University).

[59] ENVI, Evidence, 27 September 2022, 1725 (Dr. Kathryn Moran, President and Chief Executive Officer, Ocean Networks Canada).

[60] ENVI, Evidence, 27 September 2022, 1700 (Dr. Kathryn Moran); ENVI, Evidence, 27 September 2022, 1725 (Dr. Kathryn Moran).

[61] Nature Canada, Written Submission to ENVI, 4 November 2022.

[62] ENVI, Evidence, 4 October 2022, 1705 (Emmanuelle Rancourt, Coordinator and Co-spokesperson, Vision Biomasse Québec).