PACP Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS OF CANADA 2020

Background

A. The Public Accounts of Canada

The Public Accounts of Canada 2020 were tabled in the House of Commons on 30 November 2020[1] and referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (the Committee),[2] which considered them at its meeting of 26 January 2021. The following individuals took part in this meeting:

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG): Karen Hogan, Auditor General of Canada; Chantale Perreault, Principal; and Étienne Matte, Principal.

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS): Roch Huppé, Comptroller General of Canada; Roger Ermuth, Assistant Comptroller General, Financial Management Sector; and Diane Peressini, Executive Director, Government Accounting Policy and Reporting.

- Department of Finance Canada: Michael J. Sabia, Deputy Minister; Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch; and Darlene Bess, Chief Financial Officer, Financial Management Directorate, Corporate Services Branch.[3]

B. The Government of Canada’s Responsibility

The federal government is responsible for (1) the preparation and fair presentation of its consolidated financial statements in accordance with its stated accounting policies, which are based on Canadian public sector accounting standards; and (2) for such internal control as the government determines is necessary to prepare consolidated financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error.[4]

C. The Auditor General of Canada’s Responsibility and Opinion

The OAG is responsible for expressing an opinion on the government’s consolidated financial statements, based on the audit it conducted in accordance with Canada’s generally accepted auditing standards. These standards require the Auditor General to comply with ethical requirements and plan and perform the audit to obtain reasonable assurance about whether the consolidated financial statements of the government are free from material misstatement.[5] Karen Hogan, the Auditor General of Canada, stated that, in 2019–2020, the “audit of the government’s financial statements took approximately 33,000 hours to complete and involved most of our financial auditors.”[6]

Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Summary Report and Consolidated Financial Statements

A. Opinion of the Auditor General of Canada

With respect to the Public Accounts of Canada 2020, the OAG reported that the consolidated financial statements “present fairly, in all material respects, the consolidated financial position of the [Government of Canada] as of March 31, 2020, and the consolidated results of its operations, consolidated changes in its net debt, and its consolidated cash flows for the year then ended in accordance with the stated accounting policies of the Government of Canada.”[7] For the 22nd straight fiscal year, the OAG “provided the Government of Canada with an unmodified audit opinion on its … consolidated financial statements,”[8] which means that it “conclude[d] that the financial statements gave a fair presentation of the underlying transactions and events according to accounting requirements.”[9]

On this point, Roch Huppé, the Comptroller General of Canada, noted the following:

Not many national governments receive a clean audit opinion on their financial statements—let alone do so every year for two decades. I am very proud that the work of the financial management community is so strong that we can sustain this accomplishment year after year.[10]

B. Financial Performance and Financial Position

The Public Accounts of Canada 2020 outline the government’s financial performance during the 2019–2020 fiscal year and its financial position as of 31 March 2020. Some financial highlights follow:

- The government posted a deficit of $39.4 billion (1.7% of Canada’s gross domestic product [GDP]), close to triple the $14‑billion (0.6% of GDP) deficit in 2018‑2019.[11]

- The financial statements now present another measure of the deficit: the deficit before net actuarial losses. Actuarial losses and gains “arise from the annual re‑measurement of the government’s existing obligations for public sector pensions and other future benefits owed to veterans and government employees.” In 2019‑2020, net actuarial losses totalled $10.6 billion, thus the deficit before net actuarial losses was $28.8 billion. In 2018–2019, net actuarial losses totalled $8.4 billion, and the deficit before actuarial losses was $5.6 billion.[12]

- Public debt charges totalled $24.4 billion, an increase of $1.2 billion (5.1%) from the previous fiscal year.[13]

- As of 31 March 2020, the accumulated deficit (the difference between total liabilities and total assets) was $721.4 billion (31.3% of GDP), compared with $685.5 billion (30.8% of GDP) in the previous fiscal year.[14]

C. Source of and Growth in Revenues and Expenses

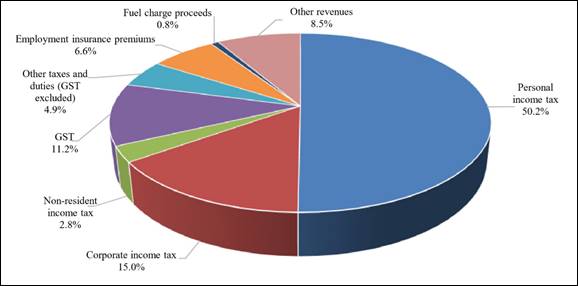

Figure 1 shows the composition of federal government revenues in 2019–2020. Revenues totalled $334.1 billion, an increase of $1.9 billion (0.6%) from the previous fiscal year.[15]

Figure 1—Sources of Federal Revenue, 2019–2020

Source: Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 15.

Figure 2 illustrates the growth in the various types of federal revenues in 2019–2020 and their average annual growth from 2013 to 2019.

Figure 2—Average Annual Growth Rate (2013–2019) and Annual Growth Rate (2019–2020) for the Various Types of Federal Revenues (%)

Source: Figure prepared using data from Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 39.

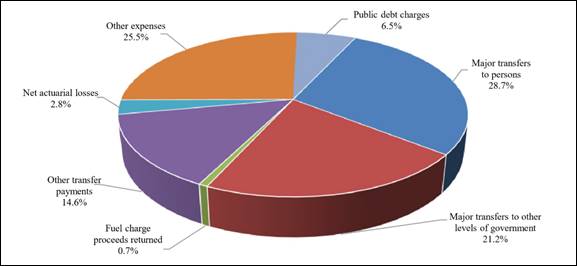

Figure 3 shows the composition of federal government expenses in 2019–2020. They amounted to $373.5 billion, an increase of $27.3 billion (7.9%) from the previous fiscal year.[16]

Figure 3—Figure 3 – Sources of Federal Expenses, 2019–2020

Source: Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 18.

Figure 4 shows the growth in the various types of federal expenses (excluding net actuarial losses) in 2019–2020 and their average annual growth from 2013 to 2019. The increase in public debt charges is “largely reflecting higher Consumer Price Index adjustments on Real Return Bonds, an increase in the stock of Government of Canada treasury bills, and higher costs associated with marketable bonds.”[17]

Personnel expenses increased by $5.9 billion or 11.9% in 2019-2020. This increase was partly due to an increase of $4 billion in wage expenditures that can be attributed “to a combination of employment growth and average salary increases,”[18] of 3.7 % and 2 to 2.4% respectively. The other part of the increase ($1.9 billion) “was due to increases in current service costs for public sector pensions and other employee and veteran future benefits.”[19]

Figure 4—Average Annual Growth Rate (2013–2019) and Annual Growth Rate (2019–2020) for the Various Types of Federal Expenses (%)

Source: Figure prepared using data from Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 39.

Of particular note, the federal fuel charge “began applying in Ontario, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, effective April 1, 2019; in Nunavut and Yukon, effective July 1, 2019; and in Alberta, effective January 1, 2020.”[20] Fuel charge proceeds totalled $2.7 billion in 2020. In theory, “all direct proceeds from the federal fuel charge are returned to the jurisdiction of origin.” These returns amounted to $2.6 billion in 2019‑2020.[21]

Nicholas Leswick of Finance Canada explained why the figures for proceeds and returns were different, saying that “there is a slight discrepancy. It’s under $20 million on a $2.6‑billion program, [and is] just a matter of revenue and expense recognition over the accounting period.”[22] Mr. Leswick assured the Committee that “every dollar that is collected through the fuel charge will be returned to the payers in the jurisdiction in which it was paid.”[23] He added that the revenue from the charge “does go back to Canadians through the climate action incentive payment, which is administered through the personal income tax system.”[24] In a written response to the Committee, Finance Canada specified that in reality, around 90% of these revenues were returned this way to individuals in Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan. The rest of the proceeds “are used to support small businesses, schools, universities, municipalities, and Indigenous groups.”[25] In Prince Edward Island, Yukon and Nunavut, the direct proceeds are returned to the governments of these jurisdictions.

In the same response, Finance Canada explained that “the price paid by consumers on goods and services would usually have the costs of the fuel charge embedded”[26] and that the goods and services tax/harmonized sales tax (GST/HST) “is calculated on the final amount charged for a good or service.”[27]

Similarly, following a question of the Committee, TBS sent a written answer prepared by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC), in which the department presented the various types of compensations, liabilities and trust monies related to First Nations:

- Payments of Claims against the Crown represent compensation for litigation claims settled out of court. They totalled $2.1 billion in 2019-20, a significant increase “compared to previous fiscal years given the recent settlements of the McLean and Sixties Scoop class actions.”[28]

- Payments for specific claims, special claims and comprehensive land claims from First Nations totalled $853 million in 2019-20 and $1.6 billion in 2018-2019.

- CIRNAC contingent liabilities “include potential liabilities for specific claims, special claims and comprehensive land claims, which are on the basis of historic treaties or existing rights and titles.”[29] These liabilities totalled $19.6 billion as of 31 March 2020.

- “Contractual obligations are financial obligations of the government to others that will become liabilities when the terms of those contracts or agreements are met,”[30] and totalled $3.4 billion as of 31 March 2020.

- Finally, “the Department of Indigenous Services reports in its financial statements trust moneys it administers on behalf of bands and individuals, amounting to $598M as at March 31, 2020.”[31]

D. COVID-19 Pandemic

In March 2020, the government launched Canada’s COVID‑19 Economic Response Plan. The plan’s impact “on the financial results of the government will largely be felt in the 2021 fiscal year. A relatively small share of the Plan is reflected in the 2020 budgetary results, including $6.5 billion for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), $0.5 billion in support for provincial and territorial public health preparedness and critical health care systems, and $0.2 billion for national public health pandemic operations.”[32] Nicholas Leswick explained that the pandemic also affected government revenues in March 2020: “there were two weeks in the year where there was a huge shock to revenue as the economy virtually shut down overnight. We estimate that even on the revenue side the shock was between $7 billion and $10 billion.”[33]

These decreased revenues, combined with increased expenses, will continue in 2020-21 and should appear in the Public Accounts of Canada 2021: “the severe deterioration in the economic outlook plus the temporary measures implemented through the government’s economic response plan are expected to result in a projected deficit of $343.2 billion in fiscal year 2021.”[34] Karen Hogan indicated that “the pandemic will also significantly affect the government's 2020-21 financial statements.”[35]

E. Public Debt

Nicholas Leswick explained that it was necessary “to put G7 countries on a comparable basis to compare their respective debt loads.”[36] This debt load was reported in the Public Accounts of Canada 2020 – according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), “Canada’s total government net debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 25.9% in 2019, … the lowest level among G7 countries, which the IMF estimates will record an average net debt of 88.1% of GDP in that same year.”[37]

According to Michael Sabia, Deputy Minister, Finance Canada, “growth is fundamental to the well-being of Canadians, … and it's fundamental to our ability to manage our debt over time.”[38] He also explained that growth projections “are very difficult to make, given the situation”[39] and that “as a result of those lockdown activities, that's having an impact, and that will probably lead us to a world of somewhat lower growth than that number [of a 5.5% projected growth for 2021] would have suggested.”[40]

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada’s Commentary on the Financial Audits

For the past five years, the OAG has published a document separate from, but tabled at the same time, as the Public Accounts of Canada: the Commentary on the Financial Audits. This document includes a section entitled “The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s consolidated financial statements” and another section called “Results of our financial audits.”

A. Observations of the Auditor General

1. Pay Administration

This year, the OAG chose to test only the errors in pay administration affecting the basic and acting pay of a sample of employees, as these types of payment account for 92% of the $26 billion processed by the Phoenix pay system.[41]

In 2019–2020, 51% of employees received incorrect basic or acting pay, compared with 46% in 2018–2019. However, as of 31 March 2020, 21% of employees still had to have their pay corrected, compared with 39% as of 31 March 2019. The number of employees with outstanding pay action requests (processed by the Public Service Pay Centre) decreased from 171,600 as of 31 March 2019 to 156,400 as of 31 March 2020 and to 144,300 as of 30 June 2020.[42] Karen Hogan commented, that despite “the significant number of individual pay errors, overpayments and underpayments partially offset each other. As a result, the pay errors did not significantly affect the government’s financial statements. However, the underlying problems and the errors continued to affect thousands of employees.”[43]

The OAG’s testing identified problems with the quality of human resources (HR) and pay data, particularly owing to late reporting of information by departments and agencies to the Public Service Pay Centre.[44] The OAG expressed concern that, “if the government transitions to a new pay system, it could repeat weaknesses in the HR-to-pay process and continue paying employees inaccurately. For example, if data quality problems persist, they could result in errors in employee pay, regardless of which system processes the pay transactions.”[45] Roch Huppé, the Comptroller General of Canada, stated that “people are working very hard to remedy the current situation”[46] and that the government is “designing and implementing a new system.”[47]

Karen Hogan explained that, “at the current rate of processing of pending payroll intervention requests, these will not be resolved until 2022.”[48] She added that “there will always be requests for payroll intervention in any given period. That said, the government needs to improve its process around the management and sharing of information between departments.”[49]

The Committee would like the government to continue its efforts to reduce the number of errors in pay transactions and the number of outstanding pay action requests. To that end, it previously presented two reports to the House of Commons on the Phoenix pay system, one examining the government’s response to its problems,[50] the other analyzing how these problems occurred.[51]

2. National Defence Inventory and Asset Pooled Items

The OAG noted that for the past 17 years it has expressed “concerns about National Defence’s ability to properly account for the quantities and values of its inventory.”[52] As of 31 March 2020, “inventories at National Defence were valued at about $5.1 billion (or about 83% of the government’s total inventories). Asset pooled items were valued at about $3.6 billion and were included in the government’s tangible capital assets.”[53] Karen Hogan explained that, this year, the OAG had “estimated that the department’s inventory and asset pooled items were understated by about $759 million out of a total of $8.7 billion.”[54]

In fiscal year 2016–2017, National Defence submitted a 10‑year action plan for managing its inventory to the Committee. The OAG remarked that National Defence had “made progress over the past year in its review of how it classifies items as either inventory or asset pooled items” and that it encouraged “National Defence to finalize its work in this area, including continual monitoring to further improve the accuracy of these balances.”[55] Karen Hogan also stated that “National Defence continued to implement the long-term action plan it submitted to this committee in 2016. In our view, errors in reporting quantities and values are likely to continue until the plan is fully implemented.”[56] Roch Huppé added the following:

I’m hoping the improvements will continue. I think there is an expectation that most of the remaining items will be completed this year. Hopefully, we should see an improvement in how the inventory is managed.[57]

3. Payments by the Department of Finance Canada

On 1 April 2019, the Minister of Finance entered into an agreement with the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador that stipulated that the federal government would provide it with $3.3 billion over 38 years in connection with the Hibernia offshore oil project. According to the OAG, “the Department of Finance Canada made payments totalling $135 million to the province, through a payment mechanism,” and “these payments were made without the proper legislative measures having been introduced. The department therefore did not obtain the authority of Parliament” to make them.[58]

Michael Sabia responded that the federal government “does believe it had authority under the Financial Administration Act for that payment.”[59] He explained that the payment had been included in the supplementary estimates and that, for future cases, the government is “working now on finding the best way of regularizing this, fully in the spirit of the comments and concerns that have been expressed by the Auditor General.”[60] Karen Hogan said that, “initially that was not properly obtained, but including it in supplementary estimates (B), that measure going forward to have Parliament authorize that payment, satisfies the concern we raised.”[61]

B. Results of the 2019–2020 Financial Audits

The OAG expressed satisfaction with the “timeliness and credibility of the financial statements prepared by 68 out of the 69 government organizations [it audits], including the Government of Canada,” and stated that it expects to issue the outstanding audit opinion on National Defence’s Reserve Force Pension Plan in late 2020.[62]

The OAG identified three instances of non-compliance during its financial audits, two of which involved Ridley Terminals Inc., which the federal government has since sold.[63] The other case concerned the Canada Development Investment Corporation; the OAG produced a special examination report on this matter in 2018.

The OAG submits letters of recommendation to departments and agencies following financial audits. Of the “total management letter points that were unresolved as of 30 June 2020, 40% have been unresolved for 2 years or more, 28% have been unresolved for between 1 and 2 years, and another 32% were newly issued within the past year.”[64] The OAG found that “more than one third of the unresolved management letter points as of 30 June 2020 resulted from [its] reviews of IT general controls over systems supporting financial reporting.”[65] In addition, “most of these unresolved management letter points related to the need to improve controls over the access granted to organizations’ IT systems.”[66] Karen Hogan explained that “it is really just a best practice that you should make sure that those who have access have the right access to the right information and only when they need it.”[67]

The OAG “informed organizations of the need to correct these important points because strong access controls are needed to safeguard the integrity of the government’s data.”[68] The Committee is troubled by this situation and expects the departments and agencies in question to immediately explain to the OAG how they intend to resolve the points that were brought to their attention.

Potential Changes to the Public Accounts of Canada

In his opening statement, Roch Huppé mentioned that the Office of the Comptroller General is considering changes to the presentation and format of the Public Accounts of Canada:

There have been no significant changes to the form and content of the public accounts since the government moved to accrual accounting in 2003. With more, and timelier, online reporting of information, I feel that there would be merit in examining the current practice of presenting information annually in three volumes totalling over 1,200 pages. As well, I believe some of the thresholds of reporting have not been increased in 40 years and could be changed, such as in the sections on payments of claims against the Crown, as well as losses of public money and property.[69]

The Committee encourages the Office of the Comptroller General to consider appropriate changes that could improve the presentation and accessibility of the Public Accounts of Canada and thus recommends the following:

Recommendation 1

That the Office of the Comptroller General, at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, in consultation with the Office of the Auditor General of Canada, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts and interested parties, study potential changes to the Public Accounts of Canada to make them more user-friendly and accessible while ensuring a high degree of transparency and accountability from the Government of Canada.

Conclusion

The Committee would like to thank the Office of the Auditor General of Canada for its thorough audit. It also wishes to congratulate the Government of Canada for receiving its 22nd consecutive unmodified audit opinion, which demonstrates that it properly reported its overall financial performance in 2019–2020 to Parliament and to Canadians.

However, the Committee remains concerned about the errors caused by the Phoenix pay system reported by the Office of the Auditor General and urges the federal government to continue its work to reduce the number of pay errors and outstanding transactions. The Committee is also making one recommendation to improve the presentation of the Public Accounts of Canada.

Finally, the Committee anticipates that the Government of Canada’s public finances will be significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which incurred a significant decrease in revenues and an unprecedented increase in expenses, which in turn will be reflected in the Public Accounts of Canada 2021. The Committee expects the Government of Canada to continue to rigorously report its revenues and expenses in 2020-21 and that the Office of the Auditor General maintain its high-quality standards in auditing the next edition of the Public Accounts of Canada.

[1] Receiver General for Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2020.

[3] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Minutes of Proceedings, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021.

[4] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 2 – Consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 52.

[5] Ibid.

[6] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1110.

[7] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 2 – Consolidated financial statements of the Government of Canada,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 52.

[8] Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG), “Results of our 2019–2020 financial audits,” Commentary on the 2019–2020 Financial Audits.

[9] OAG, “Unmodified audit opinion,” Financial Audit Glossary.

[10] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1115.

[11] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 12.

[12] Ibid., pp. 13 and 14.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., p. 13.

[18] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), Follow-up Responses to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (PACP), p. 1.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 16.

[21] Ibid.

[22] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1135.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., 1150.

[25] Finance Canada, Response to Committee Undertaking, p. 2.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] TBS, Follow-up Responses to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts (PACP) prepared by Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 11.

[33] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1220.

[34] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 9.

[35] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1110.

[36] Ibid., 1225.

[37] Receiver General for Canada, “Section 1 – Financial statements discussion and analysis,” Public Accounts of Canada 2020: Volume I, p. 34.

[38] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1225.

[39] Ibid., 1230.

[40] Ibid.

[41] OAG, “Pay administration,” The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019‑2020 consolidated financial statements.

[42] Ibid.

[43] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1110.

[44] OAG, “Pay administration,” The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019‑2020 consolidated financial statements.

[45] Ibid.

[46] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1235.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid., 1140.

[49] Ibid.

[50] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Report 1, Phoenix Pay Problems, of the Fall 2017 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada – Part I, Forty-second Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, March 2018.

[51] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Report 1, Building and Implementing the Phoenix Pay System, of the 2018 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, Fifty-third Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, November 2018.

[52] OAG, “National Defence inventory and asset pooled items,” The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019–2020 consolidated financial statements.

[53] Ibid.

[54] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1110.

[55] OAG, “National Defence inventory and asset pooled items,” The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019–2020 consolidated financial statements.

[56] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1110.

[57] Ibid., 1210.

[58] OAG, “Department of Finance Canada payments,” The Auditor General’s observations on the Government of Canada’s 2019–2020 consolidated financial statements.

[59] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1150.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Ibid.

[62] OAG, “Results of our 2019–2020 financial audits,” Commentary on the 2019–2020 financial audits.

[63] Ibid.

[64] OAG, “Opportunities for improvement noted in our 2019–2020 financial audits,” Commentary on the 2019‑2020 financial audits.

[65] Ibid.

[66] Ibid.

[67] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1145.

[68] OAG, “Opportunities for improvement noted in our 2019–2020 financial audits,” Commentary on the 2019‑2020 financial audits.

[69] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Evidence, 2nd Session, 43rd Parliament, Meeting No. 14, 26 January 2021, 1120.