HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Indigenous housing: the direction home

Introduction

Access to safe, affordable housing is essential to the health and well-being of all Canadians. Moreover, adequate housing is a fundamental human right that was recently recognized by the federal government and Parliament in the National Housing Strategy Act.[1] Housing is also referenced in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other United Nations human rights treaties and declarations to which Canada is a signatory. For example, article 21 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that Indigenous peoples have the right to the improvement of their social and economic conditions including housing. The Minister of Justice recently introduced a bill in the House of Commons on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Despite these initiatives, many Indigenous peoples have lacked access to safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing for too long. Some witnesses referred to the housing situation for First Nations living on reserve, Inuit, and urban Indigenous peoples as a ‘crisis.’[2] The COVID-19 pandemic has made this urgent situation worse by exacerbating existing housing challenges. As explained by one witness, Indigenous peoples in urban, rural, and remote areas are “experiencing gross and systemic violations of the right to housing.”[3]

These housing challenges are well documented in major reports including the final reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. Some reports include recommendations related to housing. For example, Call for Justice 4.6 of the Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls calls upon all governments to “immediately commence the construction of new housing and the provision of repairs for existing housing to meet the housing needs of Indigenous women, girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people.”[4]

In light of the lack of safe, affordable and culturally appropriate housing for Indigenous peoples living-off reserve, the Committee adopted the following motion on 9 October 2020:

That, in recognition of the fact that nearly 80% of the Indigenous Peoples in Canada live in Urban, rural and northern communities; be it resolved that pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the committee undertake a study to investigate and make recommendations on the challenges and systemic barriers facing Indigenous People and Indigenous housing providers in northern, urban and rural communities across Canada; that this study focus on urban, northern and rural providers and identify the gaps in the federal governments current policies in addressing homelessness and the precarious housing crisis facing Indigenous people in urban, rural and northern communities across Canada and that pursuant to Standing Order 109, the committee request that the government table a comprehensive response to the report.

Over the course of the study, the Committee held eight meetings between 17 November 2020 and 16 February 2021, hearing from more than 30 witnesses including representatives from Indigenous and non-Indigenous service-delivery organizations, First Nations communities, associations, and academics. The Committee also received seven briefs from interested organizations. The Committee would like to thank everyone who took the time to share their personal stories, insight, and advice based on many years of experience working on Indigenous housing.

As part of the study, the Committee adopted a motion requesting that the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) prepare a costing report. The report was to include the unit cost of addressing Indigenous housing needs and homelessness through various policy options, and an assessment of provincial transfers and expenditures on urban, rural, and northern Indigenous housing, among other matters. The PBO’s report was released on 11 February 2021.

This report focuses on Indigenous peoples in Canada living off reserve,[5] who make up the majority of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Indigenous peoples living off reserve are diverse and live in urban, rural, and northern areas of this country. Like First Nations living on reserve, Indigenous peoples living off reserve experience a shortage of safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing which impacts their health and well-being. Indigenous peoples living off reserve are more likely to experience core housing need[6] compared to non-Indigenous people and are also overrepresented among those experiencing homelessness. A young and growing Indigenous population puts pressure on existing housing needs.

First, this report provides background information on Indigenous peoples living off reserve to contextualize the challenges Indigenous peoples living off reserve face in accessing safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing. Finally, it provides recommendations to support Indigenous-led housing solutions, including developing a housing strategy for urban, rural, and northern Indigenous housing. We hope that this report and its recommendations will help to achieve the vision described by one witness: “that one day, urban, rural and remote Indigenous peoples will experience the same access to housing and services afforded to all other Canadians and distinction-based nations [First Nations, Inuit and Métis].”[7]

Background

This section contains background information to help contextualize the housing challenges and solutions discussed in this report. First, it provides an overview of the Indigenous population living off-reserve. Finally, it describes the roles and responsibilities for housing for Indigenous peoples living off reserve.

Overview of Indigenous Peoples Living Off Reserve

In 2016 about 1.7 million people identified as Indigenous, including 65,025 Inuit, 587,545 Métis and 977,230 First Nations. As shown in the below graph, Indigenous peoples live in communities across Canada including on reserve, off reserve and in urban centres.

Figure 1–Percentage and Total Numbers of Indigenous People Living On Reserve, and Off Reserve in Urban and Rural/Northern Areas and in Inuit Nunangat

Source: Figure prepared by authors using data from Statistics Canada, 2016 Census.

Notes: The population figures for rural and northern regions do not include Inuit Nunangat. The population of Inuit Nunangat includes all individuals in Inuit Nunangat who report an Indigenous identity. Urban refers to individuals who live in Census Metropolitan Areas (CMA). A CMA must have a total population of at least 100,000 of which 50,000 or more must live in the core based on adjusted data from the previous Census of Population Program.

Both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada are increasingly moving to cities. In 2016, 83% of the total Canadian population of about 35 million lived in a city.[8] This trend is also seen in the Indigenous population; more than half (51.8%) of the total Indigenous population of approximately 1.7 million people were living in a metropolitan area in 2016.[9] The urban Indigenous population continues to grow: between 2006 and 2016, the number of Indigenous people living in metropolitan areas increased by nearly 60%.[10] Based on data from the 2016 census, the following map shows the total population that identifies as Indigenous in selected census subdivisions across the country and as a percentage of the overall population in each subdivision.

Figure 2–Indigenous Population of Selected Census Subdivisions in Canada

Source: Map prepared by Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 2020, using data from Statistics Canada, “Census Profile Tables,” Census of Population, 2016, accessed February 2020 through CHASS; Statistics Canada, 2016 Census – Boundary files; Natural Resources Canada [NRCan], “Administrative features,” Administrative boundaries in Canada – CanVec Series, 2018; and NRCan, “Hydrographic features,” Lakes, rivers and glaciers in Canada – CanVec Series, 2018. The following software was used: Esri, ArcGIS Pro, version 2.4.3. Contains information licensed under Statistics Canada Open Licence Agreement and Open Government Licence – Canada; © 2020 Esri and its licensors.

Indigenous peoples living off reserve are a diverse group of people with different languages, histories, cultures, and experiences living in urban, rural, and northern communities across Canada. Indigenous peoples living off reserve have varying degrees of connection to their home communities. One witness described Indigenous peoples living off reserve as “the dispossessed, the disenfranchised, from our sense of belonging to the three distinctions-based groups, having founded our own sense of community and belonging in the urban, rural and northern environments. We are the non-status, the status unknown, the migrating and the immigrant of the spectrums you refer to as distinctions-based groups.”[11] As explained in a brief by the Aboriginal Housing Management Association (AHMA), some urban Indigenous people do not have an Indigenous governing body to represent them, leaving them without a voice or “meaningful representation from elected officials at either the provincial or federal levels.”[12]

Roles and Responsibilities for Housing for Indigenous Peoples Living Off Reserve

This section will explore the roles and responsibilities of different levels of government for housing for Indigenous peoples living off reserve. As context, the federal role in housing for First Nations on reserve is also discussed.

The federal government provides funding for housing on reserve through programs such as the First Nation On-Reserve Housing Program. In recent years, the federal government has also proposed to provide funding for the development of housing strategies for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. This is the first time that the federal government will provide targeted funding for Métis housing.

In some cases, federal funding is provided through targeted programs for Indigenous peoples living off reserve. The federal government provides funding to support housing built prior to 1993 under the Urban Native Housing Program and the Rural and Native Housing Program.[13] The federal government also provides support for housing through the National Housing Strategy and transfers, such as the Canada Social Transfer, to provincial and territorial governments that may support housing for Indigenous peoples living off reserve.[14]

The Committee heard that provincial and territorial governments are involved in the delivery of housing programs that may support Indigenous peoples living in urban, rural, and northern areas.[15] Some provinces, including British Columbia and Quebec, have specific targeted programs and initiatives for Indigenous housing.[16] Indigenous peoples may also be eligible for affordable housing programs open to all provincial and territorial residents.

Witnesses suggested that provinces and territories may take different approaches to supporting housing and homelessness initiatives for Indigenous peoples living off reserve.[17] For example, in British Columbia, following a series of negotiations, the provincial government transferred the administration of all federal and provincial Indigenous social housing programs to AHMA.[18] AHMA has over 40 Indigenous housing providers as members and is “Canada’s first Indigenous grassroots housing authority.”[19] In contrast, a brief submitted to the Committee by the Native Council of Prince Edward Island described the province’s approach in supporting off‑reserve Indigenous housing as “dismal at best.”[20]

Some Indigenous groups have signed modern treaties and/or self-government agreements.[21] Self-government agreements provide Indigenous communities with control over their internal affairs including decisions about program and services, which in some cases may include housing. Therefore, Indigenous governments may also play a role in housing for Indigenous peoples living off reserve.

Indigenous organizations play a role in providing housing programs and services to Indigenous peoples living in urban, rural, and northern areas. Over the past several decades, Indigenous peoples established a number of organizations that deliver programming to First Nations, Inuit, or Métis specifically, or to Indigenous peoples more generally. For example, Friendship Centres arose out of the migration of Indigenous people from reserves to urban centres, especially following the world wars.[22] They were established to support this migration and provide a place to come together for referrals for community services.[23] Today, Friendship Centres across Canada are identified as service hubs offering programs in a number of areas including employment, education, health, addictions, violence prevention, and emergency shelters among others.[24] Friendship Centres were also central to the creation of some small Indigenous housing delivery organizations which emerged between the 1970s and the 1990s to address the lack of adequate housing and discrimination from prospective landlords.[25]

Indigenous peoples developed their own organizations in urban centres to address Indigenous housing needs. These organizations often have decades of experience delivering housing programs and services to Indigenous peoples. For example, the Lu’ma Native Housing Society in Vancouver, British Columbia was established in 1980 with the “simple dream of providing affordable housing to Indigenous peoples.”[26] Since then, the Lu’ma Native Housing Society has developed into an organization that provides a range of services including social, affordable and modular housing, youth programs, medical services, and homelessness services.[27]

Federal Housing Programs

Several federal departments including Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and a Crown Corporation, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) offer programming and funding that can be accessed by Indigenous peoples living off reserve. This section provides examples of programs and initiatives that are discussed later in this report. Additional information on federal housing programs is included in appendix A.

As explained by officials, CMHC offers funding and financing options that support Indigenous and northern housing needs through the National Housing Strategy launched in 2017.[28] One initiative under the Strategy known as the National Housing Co‑Investment Fund supports the construction of new or the revitalization of existing mixed-income, mixed-tenure, and mixed-use affordable housing. Within the Fund, $25 million was dedicated to Indigenous housing projects.[29] Eligible projects include those focussed on Indigenous housing in urban centres, shelters, and transition housing. Over the past two years, CMHC provided more than $121 million through this Fund to support 577 units to address Indigenous and northern housing needs. The Fund also includes a $125 million set aside for specific needs such as repairs to urban Indigenous housing and projects in northern Canada.[30] Further, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Committee heard that CMHC is delivering a new shelter initiative to fund the construction of 12 shelters for Indigenous women and children across the country over the next five years.[31] In terms of northern housing, CMHC noted that $447 million provided to the Territories through bilateral agreements, although not Indigenous-specific, will also support housing Indigenous people living in the North.[32]

Another CMHC program is the Rapid Housing Initiative which proposes to provide $1 billion to address urgent housing needs by quickly building affordable housing. The fund includes $500 million for cities selected based on severity of housing need.[33] Cities must provide an investment plan as part of their application and CMHC looks for at least 15% of the projects to be prioritized for Indigenous peoples.[34] The Rapid Housing Initiative also includes $500 million for projects allocated through an application process open to non-profits and other organizations across Canada, among others.[35] While CMHC has a prioritization process for projects under the initiative, there is no dedicated funding for the North.[36] The Committee heard from several witnesses who were in the process of developing or had already filed applications under the Rapid Housing Initiative.[37] The Committee is seized with the Rapid Housing Initiative and is currently working on a separate parallel examination of this issue with witnesses.

Further, in Budgets 2017 and 2018, the federal government proposed to allocate funding for the development of housing strategies for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis as follows:

- $600 million over three years for a First Nations housing strategy and the repair and construction of housing units on First Nations reserves;

- $400 million over 10 years to support the Inuit Nunangat Housing Strategy[38] and the repair/construction of housing units in Nunavik, Nunatsiavut and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region; and

- $500 million over 10 years to support a Métis Nation Housing Strategy.

CMHC, Indigenous Services Canada and Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada are working with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis organizations people in developing the distinctions-based housing strategies.[39] The Inuit Nunangat Housing Strategy was released in 2019, and the Métis Nation and the Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations signed the Métis Nation Housing Sub-Accord in July 2018. It is unclear when the First Nations housing strategy will be released.

As mentioned above, ESDC also provides support for housing related programming for Indigenous peoples living off reserve. The department manages Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy (Reaching Home), a community-based program that supports the goals of the National Housing Strategy by aiming to prevent and reduce homelessness. In all provinces except Quebec, community entities, which in some cases are Indigenous organizations, are provided with direct funding through a contribution agreement and can select, approve and manage projects in their area based on the local community homelessness plan and priorities.[40] In Quebec, the program is delivered through an agreement between the province and the federal government.[41]

Reaching Home has four regional funding streams dedicated to addressing local homelessness in the Territories as well as in urban, Indigenous, rural, and remote communities. Indigenous organizations providing homelessness related supports and services to Indigenous peoples are eligible to apply for funding under the Designated Communities, Rural and Remote Homelessness and Indigenous Homelessness funding streams.[42] The Territorial Homelessness funding stream provides funding for homelessness-related services and supports in the territories. Even though it is not specific to Indigenous peoples, it does include Indigenous homelessness given the proportion of Indigenous peoples living in the Territories.[43] Through the program, the federal government proposes to provide $413 million over nine years for Indigenous homelessness, including:

- $261 million through the Indigenous homelessness stream to “maintain the community-based approach and help organizations provide culturally appropriate services to Indigenous people;”[44] and

- $152 million for the development and implementation of “distinctions-based approaches to homelessness.”[45]

With respect to funding for distinctions-based approaches to homelessness, ESDC officials told the Committee that the department is working with national Indigenous organizations to identify homelessness priorities and sign funding agreements. The department indicated that it is also exploring the possibility of providing funding for modern treaty holders.[46] Indigenous communities in the territories may also benefit from the proposed $42.5 million over nine years allocated to the territorial homelessness stream.[47]

Several departments are also involved in the Indigenous Homes Innovation Initiative which aims to “support Indigenous-led, community driven projects, that could serve as blueprints for new approaches.”[48] Launched in April 2019, the five-year initiative is a partnership between Indigenous Services Canada, Infrastructure Canada, and the Impact and Innovation Unit of the Privy Council Office.[49] The initiative is guided by an Indigenous Steering Committee and selected innovators could receive funding for the development of their ideas and implementation of their projects. In January 2020, the administration of the initiative was transferred to the Council for the Advancement of Native Development Officers. Indigenous Services Canada provides policy, technical and other support if required.[50] The department plans to spend over $40 million on this Initiative between 2018-2019 and 2022-2023.[51]

The Shortage of Safe, Adequate, Affordable, and Culturally Appropriate Housing in Indigenous Communities

Indigenous peoples, including those living off reserve, are experiencing a shortage of safe, adequate, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing. It is important to note that Indigenous understandings of home and homelessness may be different from non‑Indigenous perspectives.[52] As explained in a reference document submitted to the Committee, this means that adequate and appropriate housing for urban Indigenous peoples requires an understanding of the housing needs and experiences of urban Indigenous peoples.[53]

While there may be differences between local contexts, specific types of housing needed and housing priorities between Indigenous groups and communities, there are many common themes that underlie their housing challenges. The following section will discuss the housing shortage experienced by Indigenous peoples living off reserve including rates of core housing need and affordability challenges in urban, rural, and northern areas.

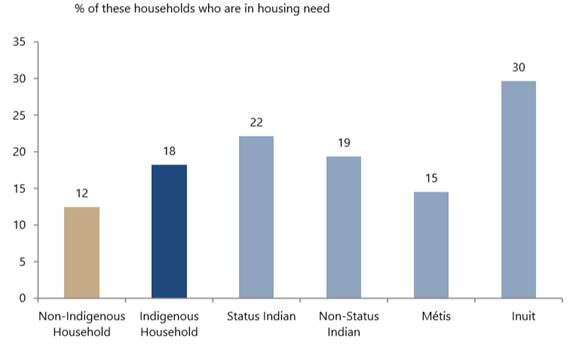

As shown in figure 3, Indigenous off-reserve households are more likely to be in core housing need than non-Indigenous households.

Figure 3–Incidence of Housing Need in Canada

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Urban, Rural and Northern Indigenous Housing, 11 February 2021, p. 7.

Notes: An Indigenous household has at least one spouse, common law partner, or lone parent who self-identified as an Indigenous person; or at least 50 per cent of household members self-identified as an Indigenous person.

The PBO estimated that of 677,000 Indigenous off-reserve households in Canada, 124,000 (18%) were in housing need in 2020.[54] Indigenous off-reserve households comprise less than 5% of all households in Canada yet Indigenous off-reserve households account for 7% of all households in core housing need.[55] Inuit are more likely to be in core housing need; the probability of being in housing need for Inuit households is 2.4 times greater than for non‑Indigenous households.[56]

While there are regional differences in the level of core housing need, Indigenous households are more likely than non-Indigenous households to be in core housing need in all provinces and territories. The Territories have the highest incidence of housing need, yet only 5% of all Indigenous households in housing need live in the Territories.[57] Across Canada, 57% of Indigenous households in housing need live in a census metropolitan area. Winnipeg has the highest number of Indigenous off-reserve households in housing need (about 9,000), while Vancouver has the second highest (about 8,000).[58]

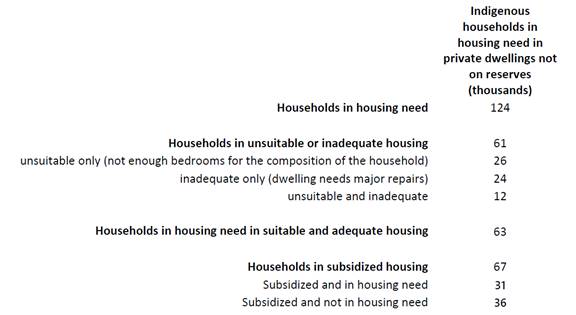

There are a number of components to core housing need including housing adequacy, suitability, and affordability. Indigenous households may be in core housing need for different reasons. For instance, half of Indigenous households live in suitable and adequate housing but are in core housing need because their housing is not affordable. In 2020, it was estimated that 31,000 of 124,000 Indigenous households in housing need lived in subsidized housing.[59] Indigenous peoples in housing need are 1.2 times more likely to live in inadequate and/or unsuitable housing than non-Indigenous households in core housing need.[60] The figure below provides a breakdown of Indigenous households in core housing need by adequacy and suitability including information for those in subsidized housing.

Figure 4–Indigenous Households in Housing Need by Adequacy, Suitability and Subsidization

Source: Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, Supplementary information requested during the appearance of the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer at the proceedings of the Committee for its study of Urban, Rural and Northern Indigenous Housing, p. 4.

Note: The table is based on 2016 census data adjusted for population growth.

Housing affordability is a key issue facing many Indigenous peoples off-reserve and a factor contributing to the high number of Indigenous households in core housing need. Indigenous peoples struggle to find affordable housing in urban centres. For example, the Committee heard that in downtown Montreal, there’s a lack of affordable housing on the market.[61] In Vancouver for example, the high cost of housing contributes to the level of Indigenous housing need.[62] Even with comparable incomes, Indigenous households were more likely to be in housing need than income-equivalent non-Indigenous households.[63] The PBO estimated that there is a $636 million annual gap[64] between what Indigenous households in housing need pay for shelter and what CHMC defines as affordable housing (no greater than 30% of a household’s pre-tax income).[65] Where Indigenous households pay more than 30% of their annual income on housing, they have limited income available for other matters that can improve their health and well-being such as nutritious food, involvement in recreation programs, and non-emergency health care or dental services.[66] The gap varies by city as for example, the PBO calculated that it amounted to $58 million in Vancouver while only $8 million in Hamilton, Ontario.[67] Market prices clearly play a significant role in housing affordability, as in areas where housing costs are traditionally lower, there are fewer Indigenous peoples living in inadequate or unaffordable housing.[68]

There are many factors contributing to housing affordability challenges. As noted by the PBO, Indigenous families are more likely to be larger than non-Indigenous families and face higher shelter costs due to the size of suitable housing.[69] Further, the Committee heard about the situation in the Lillooet area where many houses are sitting empty. Out of town homeowners are renting to contractors at “an overinflated price,” since it is easier to rent to contractors for short stays.[70] However, this practice makes it difficult for locals to access housing rentals, leading to a “zero rental ability in the Lillooet area.”[71] As explained by Bindu Bonneau, Senior Director, Operations for the Métis Urban Housing Corporation of Alberta Inc., “the need for subsidized housing and affordable housing is not going to deplete anytime soon—or ever.”[72]

Affordability is also a pressing issue for Indigenous peoples in northern Canada. The Committee heard that in northern cities and towns, the public sector is generally the main and sometimes the only affordable housing provider. Many public housing units are provided to families and it is difficult for single adults to find appropriate housing without going to the private rental market.[73] However, the market is dominated by a small number of private rental companies.[74] Further, with rents among the highest in Canada, affordable private rental options are unattainable for many northerners.[75] The lack of affordable rental options in the north means that individuals who are evicted may find themselves homeless in one of the harshest climates in the world.[76]

“[T]he YWCA transition house in Yellowknife that was burned to the ground one night, and overnight, 33 Indigenous families were homeless. All of those families were housed overnight in private market housing that sat empty, and they were able to get into private market housing through the use of a rental supplement. The reason they couldn't get into it before is that the landlord who holds a monopoly in the north actually has an illegally stated policy that they don't rent to people on welfare. The Government of the Northwest Territories, which is their primary tenant, refuses to challenge that policy under human rights legislation or in court.”[77]

While Indigenous peoples experience housing affordability challenges, Indigenous peoples may also experience racism and discrimination in the private rental market. Between the 1960s and the 1990s, Indigenous housing delivery organizations were formed to address the lack of adequate housing for Indigenous peoples and racism and discrimination in the private rental market.[78] Some organizations, such as the Native Council of Prince Edward Island continue to address discrimination through current programming. For example, the Indigenous Tenant Support Initiative informs off-reserve Indigenous tenants of their rights and responsibilities to reduce the number of evictions.[79] Community advocate Arlene Hache also described the experience of an Indigenous women from a northern community:

“an Indigenous woman from a small community in the north won the first UN [United Nations] judgment under CEDAW [Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women] against Canada and against the NWT Housing Corporation for racism and discrimination after she lost her housing due to partner violence. The UN recommended that the Government of Canada hire and train Indigenous women to provide legal advice to other indigenous women around their rights and the right to housing. That United Nations recommendation has not been fulfilled to this day.”[80]

The Committee heard that in Ontario, racism in the housing market by landlords continues to be an issue making access to affordable housing difficult for Indigenous peoples.

“[T]he Ontario Native Women's Association, did a little experiment a couple of years ago in Thunder Bay. They sent a visibly Indigenous woman to ask a landlord if something that was advertised was indeed for rent, and then got the answer “no”. Then a white woman asked 30 minutes later and was told to come to see it.”[81]

The shortage of affordable housing contributes to high levels of housing need among Indigenous peoples living off reserve, as reflected in witness estimates for the number of housing units needed to address the shortfall. The Canadian Housing and Renewal Association recommended that 73,000 units should be built for Indigenous peoples living in urban, rural and northern areas.[82] David Eddy, Chief Executive Officer of the Vancouver Native Housing Society estimated that 60,000 to 70,000 units will be required in the next 10 years to make housing more available and affordable for Indigenous peoples.[83] The Ontario Non-profit Housing Association suggested that Ontario needs to build at least 22,000 subsidized Indigenous-owned and operated units over the next 10 years to meet growing housing needs for Indigenous peoples living off reserve.[84] Given that the shortage of affordable housing affects diverse groups of Indigenous people differently, some witnesses identified specific types of housing that would be needed. Witnesses highlighted the following shortages: homes with more than three bedrooms,[85] social and deep subsidy housing,[86] and housing with wrap-around supports.[87] When asked about the importance of low-barrier safe spaces,[88] a few witnesses agreed that these are essential and needed.[89] Other witnesses and documents received by the Committee identified housing needs or shortages for specific groups of Indigenous peoples including single adults,[90] seniors and Elders,[91] young families,[92] lone parent or caregiver families,[93] and those leaving state institutions such as the criminal justice system.[94]

Ultimately, the shortage of affordable housing has left growing numbers of Indigenous peoples waiting years for a safe, affordable, and culturally appropriate home. In Regina, the Namerind Housing Corporation had a waitlist of approximately 350 families.[95] In Vancouver, the Lu’ma Native Housing Society had 6,000 applicants on their waitlist. To ensure that everyone currently on the waitlist can access housing, it was estimated that the Society would have to build 600 units every year for the next 10 years.[96] Some might lose hope “that they will ever experience the comfort of living in a house or a safe house.”[97]

As explained in a brief received by the Committee, while affordability is the biggest driver for core housing need, the number of homes in need of repair is also a key challenge for Indigenous peoples.[98] Some housing providers have aging housing stock that requires significant renovations and repairs. For example, the Métis Urban Housing Corporation of Alberta Inc.’s housing stock is aged between 45 and 70 years old with many units requiring refurbishment or demolition and rebuilding.[99] A Métis-specific senior facility owned by the Métis Capital Housing Corporation is almost 50 years old, and requires refurbishment to meet the needs of the Indigenous residents.[100]

While the study focussed on Indigenous peoples living off reserve, the Committee heard about the housing challenges faced by a few First Nations communities. First Nations on reserve are also experiencing a shortage of housing including lengthy waitlists for housing. Chief Lance Haymond of the Kebaowek First Nation estimated that 10,000 more units are needed, 8,000 units need renovation and infrastructure is needed at over 9,000 sites to meet the needs of First Nations living on reserve in Quebec.[101] In British Columbia, the Sts’ailes First Nation has 1,200 registered members but only 198 houses.[102] The housing stock in First Nations communities varies. Some communities in Quebec located in remote or isolated areas primarily have social housing units whereas others located closer to urban centres may have more homeowners.[103] However, as explained by Chief Lance Haymond, “Housing is not just social housing. We need to have a spectrum of housing that meets the various realities of communities.”[104]

The housing shortage on reserve is exacerbated by the absence of a necessary land base to pursue new housing development in some First Nations communities.[105] Further, aging housing stock and the large number of homes in need of major repairs add to existing housing challenges.[106] Chief Ralph Leon Jr. of the Sts’ailes First Nation suggested that past approaches to building housing in his community contributed to the number of homes in need of repairs today. As he told the committee:

“A lot of our homes were built in the eighties by CMHC and Indian Affairs. The contractors would come in to build a house and take as many shortcuts as they could in order to make a quick buck in our communities. That is a problem today. We're applying for funds for renovations. Why? Because we have mould in our attics. We have mould in our homes because of poor ventilation, or we're having to restore the outside of our homes because the slope of our homes and our yards isn't very well done.”[107]

The extent of the housing challenges facing First Nations on reserve is well known.[108] The Committee heard one example of a First Nations community that drew attention to its housing issues by reaching out to political leaders. Chief Ralph Leon Jr. explained that his community has communicated with Indigenous Services Canada, and their local Member of Parliament for years, and had also written letters to the Prime Minister of Canada.[109]

Factors that Contribute to the Housing Shortage

The housing challenges experienced by many Indigenous peoples are rooted in several factors, including historical policies, population growth and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Historical Policies

For Indigenous peoples the land is deeply connected to their culture, languages, and ceremonies.[110] Elizabeth Sam described the link between Indigenous peoples and the land:

“I want to talk a bit about the earth, the land and the connection that Indigenous peoples have with the earth. The earth is our home, so it is a reciprocal. If you think about sharks, whales and the small fish that eat the plankton and bacteria off the whales, that is like humans and the earth. We take care of the earth and the earth takes care of us.”[111]

The Committee heard that homelessness is related to history and must be “situated within a colonial context.”[112] Federal government policies such as residential schools, the sixties scoop, and First Nations “segregation on reserve,”[113] as well as the “general consequences of colonization,”[114] impacted Indigenous peoples and communities. This history has “displaced Indigenous peoples from the land and from our communities.”[115] Today, these policies have led to intergenerational trauma, which as explained by Elizabeth Sam, continues to affect Indigenous peoples, families, and communities:

“Intergenerational trauma and colonization—being disconnected from the land and having your identity taken away, being removed from your land and told to live somewhere else—this is where you get mental health issues, depression and anxiety. If you're away from home you lose your culture, your ceremonies and your pride in being an Indigenous person.”[116]

Together, intergenerational trauma “has had adverse affects on access to and sustainability of northern housing options.”[117]

The housing challenges facing some Indigenous peoples also have historical roots. In northern Canada, the Committee heard that the housing crisis has persisted since the first northern housing programs were established in the mid-20th century. From its beginning, northern housing was defined by inadequacy and unaffordability, issues that continue to underlie northern housing challenges today.[118] The Committee also heard that homelessness conditions worsened following 1983 when “the federal government ended the social housing program under the National Housing Act.”[119]

Population Growth

On average, the Indigenous population is a decade younger than the Canadian population.[120] In 2016, one in four Indigenous people were under the age of 15, and 33% of Inuit, 29.2% of First Nations, and 22.3% of Métis populations were children.[121] By way of comparison, 16% of the total Canadian population are children. The figure below explains this population growth.

Figure 5–Inuit, Métis, and First Nations Total and Youth Population

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, First Nations People, Métis and Inuit in Canada: Diverse and Growing Populations, 26 March 2018; and Statistics Canada, “Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census,” The Daily, 25 October 2017.

As shown in figure 6, the Indigenous population is also growing at a faster rate than the Canadian population.

Figure 6–Indigenous Population Growth Off Reserve Between 2006 and 2016

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table: 39-10-0048-01, Population in core housing need, by economic family structure and sex, accessed 19 February 2021.

The significant demographic growth in the Indigenous population between 2006 and 2016 may be explained by factors including “natural growth” where life expectancy rates improved, with relatively higher than average fertility rates. Additionally, there has been an increase in the number of people self-identifying as Indigenous on the census.[122] Ultimately, a young and growing Indigenous population puts pressure on the existing housing stock and increases the need for housing.[123]

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted the housing challenges faced by Indigenous peoples. Witnesses suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing housing challenges[124] and led more Indigenous peoples to experience homelessness.[125] Although they were housing between 120 and 140 people per month since the start of the pandemic, Homeward Trust Edmonton explained that the number of people experiencing homelessness in the community had increased from about 1,500 in 2019 to nearly 2,000 currently.[126] During the pandemic, some people experienced poverty and homelessness for the first time.[127] One witness explained that more individuals were experiencing homelessness due to the pandemic which displaced them from their communities and the correctional, health care, and child welfare systems.[128] In some cases, housing stability was impacted by the pandemic. Some individuals living in co‑housing or precarious housing lost their housing stability when their cohorts needed a place to isolate during the pandemic.[129]

Service providers experienced an increase in demand for programming as a result of the pandemic. Carol Camille, Executive Director of the Lillooet Friendship Centre Society, identified an increase in demand for mental health and addictions services, as clients unable to access services reached out to the Friendship Centre for help.[130] Public health measures put in place during the pandemic led on-reserve programming to shut down or become difficult to access as employees began to work from home.[131] The Committee heard that Friendship Centres across Canada kept their doors open, working hard to fill the gap and respond to the growing demand for services during the pandemic, often with limited resources.[132]

As demand for affordable housing continues to grow, Chief Haymond noted an increase in construction costs due to the pandemic, a situation that left him worried that fewer housing units would be built on reserve for First Nations in Quebec.[133] Currently, the number of housing units built cannot meet the demand for housing in many Indigenous communities. If construction costs increase, the Committee is particularly concerned about the potential effect on housing affordability in urban, northern, and rural communities.

Impact of the Housing Shortage

The shortage of safe, adequate, affordable, and culturally appropriate housing is an urgent situation that affects the health, safety, and well-being of Indigenous peoples. The following section will explore these health and safety impacts by discussing homelessness, the impact of the housing shortage on Indigenous youth, women, seniors, and 2SLGBTQQIA people and the migration of Indigenous peoples to urban centres.

Homelessness

Indigenous peoples may understand homelessness more broadly than lacking a home. As explained by one witness, “For indigenous people, homelessness is not just being without a home; it's being without a community.”[134] Without access to safe and affordable housing, Indigenous peoples living off reserve are overrepresented among the homeless population. Point-in-time counts enumerate and/or survey individuals experiencing homelessness at a specific moment in time. Over 19,500 people experiencing homelessness completed a survey during a 2018 national Point-in-time Count. 30% of respondents identified as Indigenous, with a majority identifying as First Nation.[135] Some witnesses referenced data from their specific regions. For example, in London, Ontario, 2% of the population is Indigenous, but Indigenous peoples represented 29% of those experiencing homelessness in 2018.[136] These statistics represent more than just numbers: they represent “the members of our communities, our nations, and in many instances our families.”[137]

Being without a home in harsh, northern climates can be a life-threatening situation that puts the health, safety, and well-being of Indigenous peoples at risk. The Committee was saddened to hear the heartbreaking stories of individuals experiencing homelessness who lost their lives. Heather Johnston, executive director of Projets Autochtones du Québec shared the story of Raphael ‘Napa’ Andre:

“My comments today are made in memory Raphael ‘Napa’ Andre. Raphael Andre was found dead earlier this month in a porta-potty in downtown Montreal. Raphael was a tall, quiet Innu man. He was loved by his family and friends, and he was well known in the street communities of Montreal. He was a member of my organization. He used our shelters frequently over for the past seven years. He was at our shelter the night before he died. We have seen a lot written about Raphael, and the cause of his death - the curfew, lack of shelter spaces and public indifference. There is perhaps some truth in all of these explanations, yet they don't tell the whole story. Raphael Andre died because he was homeless.”[138]

Homelessness is a pressing issue facing urban, rural, remote, and northern communities in Canada.[139] A brief submitted to the Committee noted that there is evidence that homelessness is equal to or more prevalent in rural communities over urban centres.[140] In rural and remote areas, homelessness is often more hidden due to a lack of available services and supports. In small communities, the lack of anonymity could mean that homeless individuals are forced off the streets and into spaces such as parks, wooded areas, and RVs. As a result, many homeless people rely on “couch surfing” which is a form of hidden homelessness.[141] Individuals experiencing hidden homelessness live temporarily with family, friends or elsewhere because they have nowhere else to go. Many Indigenous families are reluctant to turn away Indigenous people experiencing homelessness, instead inviting them to stay in their homes.[142] In some northern communities there are few shelters and it is expensive to travel to an urban centre to access services.[143] A number of family homes have become de facto shelters, taking in people who would otherwise be left out in the cold.[144] Hidden homelessness may contribute to overcrowding as large numbers of people stay in the same housing unit.[145]

The number of people experiencing hidden homelessness is difficult to determine because they are often missed in point in time counts.[146] Also, Indigenous families living in social or affordable housing might not share information about additional people living in their home for fear of eviction.[147] Hidden homelessness is an issue for all Indigenous peoples, but Indigenous women, children, and youth aging out of care are particularly affected.[148]

“[T]here is a lot of undetected homelessness in our communities, especially in the north where you can't live out on the streets. You would simply perish.”[149]

There are a number of factors that contribute to the overrepresentation of Indigenous peoples among those experiencing homelessness. Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in state systems such as the criminal justice system which may be a path to homelessness. A 2018 homeless enumeration study found that of 393 homeless individuals in the district of Kenora,[150] 18% were in jail at the time of the survey.[151] One witness explained that when Indigenous men are released from a correctional facility, they are often provided with little support and may find themselves back in the criminal justice system.[152] The housing situation for Indigenous and non‑Indigenous people in the district of Kenora led Henry Wall, Chief Administrative Officer of the Kenora District Services Board to suggest that the housing continuum[153] “has expanded to include the jails, the child welfare system, our health care system and our streets. That is not just inappropriate, but as a country we shouldn't stand for it.”[154]

Impact on Diverse Groups of Indigenous Peoples

The housing shortage may impact diverse groups of Indigenous peoples in different ways. Indigenous women, youth, seniors, 2SLGBTQQIA people, and Indigenous peoples with disabilities are more likely to need housing to escape violence, and face challenges accessing existing supports and programs.[155] For example, 2SLGBTQQIA people may also end up in urban centres when fleeing violence. However, at shelters, 2SLGBTQQIA people are at increased risk for violence and may choose not to identify themselves as a member of the 2SLGBTQQIA community.[156] Indigenous women, youth, seniors, 2SLGBTQQIA people, and Indigenous peoples with disabilities are more likely to need targeted supports “that are culturally relevant to intersectional issues they are facing.”[157] The following section provides an overview of witness testimony about the impact of the housing shortage on diverse groups of Indigenous peoples.

Impacts on Indigenous Children and Youth

Indigenous children and youth are overrepresented in the child welfare system. In 2019-2020, AHMA, an Indigenous housing authority located in British Columbia, conducted a survey and about half of its member organizations completed it. Surveyed organizations reported that 46% or 2,232 of their tenants were 18 years old or younger with 134 reported to be aging out of care in 2019-2020.[158] When Indigenous youth age out of care, they may face challenges accessing housing. In London, Ontario, high rent costs may prevent youth aging out of care from getting their own apartment in a safe location. Indigenous youth might not feel safe in a rooming house or in specific locations in the city where Indigenous youth can afford to have an apartment.[159] Together, Indigenous youth aging out of care may be more likely to end up homeless. In Vancouver, it was estimated that 50% of the 700 Indigenous youth that age out of foster care each year will end up on the streets as part of the city’s homeless population.[160]

“The child welfare system is probably the number one producer of Indigenous homelessness.”[161]

Impact on Indigenous Women

The factors leading Indigenous women to experience homelessness are different than for Indigenous men.[162] For example, some rural, remote, and northern communities lack safe or transition housing for Indigenous women and girls fleeing violence. To escape family violence and access safe housing, Indigenous families in rural and remote communities are usually taken out of their community into another regional or urban centre.[163] However, when moved out of their communities, Indigenous women “often end up losing their children to child welfare. They often end up on the street and in a different kind of violence because they're not able to navigate cities or regional centres as much as they are the communities.”[164] The Committee heard that if Indigenous parents were able to secure social or affordable housing in the city, losing their children often means eviction. However, to regain custody of their children, Indigenous parent(s) must have housing. This difficult cycle prevents some Indigenous parent(s) from maintaining meaningful and long-term connections with their children.[165]

Impact on Indigenous Seniors

Indigenous seniors are also particularly impacted by the housing shortage and may have difficulty finding culturally appropriate, barrier-free housing.[166] In the north, where services for Indigenous seniors may be unavailable, Elders and seniors are sent to other parts of Canada to access services.[167] As Indigenous peoples age, there will be a need for additional seniors housing that is affordable, accessible and culturally appropriate to meet their needs while enabling them to age in place.[168]

Impact on Indigenous Peoples with Disabilities

The housing shortage also impacts Indigenous peoples with disabilities. According to Statistics Canada, in 2017, rates of disability among Métis (30%) and First Nations people living off reserve (32%) aged 15 years or older were higher than for non-Indigenous people (22%).[169] In 2017, rates of disability among Inuit aged 15 or older (19%) were lower than for non‑Indigenous people (22%) since Inuit are a young population and research has shown that disability often increases with age.[170] Individuals experiencing homelessness may be living with a disability without a formal diagnosis. Individuals who have been diagnosed often did not have access to the appropriate assessments and supports throughout their lifetimes.[171]

Factors in the Growth of Urban Indigenous Populations

Homelessness and the housing shortage are directly connected to the migration of Indigenous peoples between their home communities and cities or larger regional centres. Indigenous peoples may move to cities permanently or temporarily for a number of reasons including to access services unavailable in their communities in rural, northern or remote areas,[172] such as shelters, health services[173] and safe and transitional housing for families fleeing violence.[174] In some cases, Indigenous peoples move to urban centres to access education or employment opportunities even though housing conditions in urban centres are often not adequate. For example, many First Nations students living in northern Ontario must travel to urban centres to complete their high school education.[175] Indigenous peoples may also move to cities to be closer to their children in care, and/or to join friends or family living in an urban centre.[176]

In other cases, Indigenous peoples may move to urban centres due to a shortage of housing in their home communities.[177] The Committee heard that this was a particular issue for First Nations living on reserve and individuals living in northern communities. One witness told the Committee about the relationship between housing and access to services, as some Elders may choose not to access medical care for fear that they will lose their housing if they leave the community.[178] In some cases, the housing conditions on reserve are so poor that some First Nations would rather be homeless in the city.[179] The COVID-19 pandemic may also impact Indigenous migration, as AHMA observed “a higher fluctuation” of Indigenous families and individuals moving between off and on reserve housing in search of more stability as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.[180]

The dislocation experienced by families who move away from their communities impacts their health and well-being and was described by one witness as akin to “being taken and moved to residential school.”[181] Families who are separated have to reconnect with new services and create family and community connections in the city.[182] Individuals may not be accustomed to living in urban centres and may have difficulty navigating and adapting to city life. In some cases, as explained by one witness, Indigenous peoples arrive with limited education, struggle to find a job and end up homeless on the streets.[183] Further, one witness shared his personal experience growing up off reserve which affected his ability to speak his language and participate in cultural activities.

“I grew up off reserve, and we were the only Indigenous family in this small town outside of Thunder Bay, Ontario, so I lost my language and any chance to learn my language. I lost any ability to participate in any real way in historical ceremonial practice and other cultural activities, but what I gained was an incredible understanding of non-indigenous peoples, other Canadians, and an understanding of the struggle with racism and discrimination. It began on the playground, but eventually most of us became friends, because we interacted with each other.”[184]

Witnesses had differing views about the role of Indigenous communities in service provision for their members in urban centres. In urban centres, Indigenous organizations are involved in delivering services to Indigenous peoples. The Committee heard that over the past 40 to 60 years, Indigenous organizations have built a service delivery infrastructure in urban centres involving thousands of board members, staff and volunteers.[185] One witness suggested that First Nations cannot serve their members living off reserve who may be situated across the country. Marcel Lawson-Swain told the Committee:

“In our scenario, if my three kids are registered to Norway House First Nation, their chief is not going to come here and meet their education, housing and health needs. It's just not going to happen. They don't have the ability and the infrastructure to do that.”[186]

Sometimes after spending years in a city, First Nation community members wish to return permanently to their communities for family cultural or other reasons. As explained by Chief Haymond, “as an Indigenous person, it's hard to live in a city after you've spent the majority of your life living in a first nation community.”[187] Moving home can positively impact health and wellness, as shared by Elizabeth Sam:

“I know that when I was living in Vancouver, before I moved home when the pandemic hit, I was feeling the effects of depression and anxiety from being away from home. Then, when I moved home in March, it was instantly just a weight off. I was feeling more at home, more myself and feeling safe again.”[188]

Ultimately, however, First Nations may be prevented from returning to their communities due to a lack of available housing on reserve, and lengthy waitlists for housing.[189] Elizabeth Sam shared the experience in her community, the Nak'azdli Whut'en First Nation: “In my community we have people who moved home 20 years ago and they're still on the waiting list for a home. Someone who just moved home last year, with their master's degree, is now on that list.”[190]

Ways to Provide More Indigenous Peoples with a Home

In this study, witnesses provided the Committee with an overview of the pressing Indigenous housing needs in urban, rural, and northern areas. While the housing challenges seem daunting, there are steps that could be taken by the federal government to move towards a future where all Indigenous peoples living in urban, rural, and northern areas have a home. This section explores some of these possible steps and opportunities.

Characteristics of Indigenous Housing Solutions

As explained in the previous sections of this report, many Indigenous peoples have difficulty accessing safe, affordable, adequate, and culturally appropriate housing. Where housing is provided, a few witnesses told the Committee that it may not meet the needs of Indigenous peoples and communities.[191] Indigenous peoples are best positioned to know what works for their communities. Witnesses shared their vision for housing by identifying characteristics important to the success of Indigenous housing initiatives including that they are Indigenous-led, support wrap-around services and contribute to building communities. The Committee believes that these important attributes should shape all federal government actions to address the housing needs of urban, rural, and northern Indigenous communities. The following section summarizes witness testimony relating to these characteristics.

Indigenous-led Solutions

Witnesses emphasized that Indigenous housing must be led by Indigenous peoples. To truly be Indigenous led, solutions must be designed, governed, managed, administered, operated, and delivered by Indigenous peoples.[192] Research, evaluation, and data collection should also be done by Indigenous peoples to ensure that it meets the needs and priorities of Indigenous peoples and communities.[193] Diverse groups of Indigenous peoples such as Indigenous women, should be involved in creating, developing and delivering their own specific solutions.[194] As explained by one witness, urban Indigenous peoples should have the opportunity and funding support to sit at the table as equal partners alongside governments during the design and creation of housing initiatives.[195] Indigenous-led solutions support self‑determination and recognize that Indigenous peoples and local Indigenous organizations are best placed to identify local housing needs, respond to housing priorities of their communities, and identify effective solutions.[196] Indigenous-led solutions are important to ensure that housing solutions address the “historical impacts of discrimination.”[197]

“[W]hen I speak about the dispossession of urban Indigenous people, we never ceded our rights as Indigenous peoples because of colonization, and so we never ceded the right and responsibility to sit as equals with the federal government.”[198]

Data on Indigenous Housing

Data is essential to support good decision making, measure current and future needs, capacity and gaps, and ensure that programs and investments are meeting diverse community needs.[199] There are numerous sources of data on housing and homelessness in Canada including federal program and expenditure data, the census and enumerations/surveys of people experiencing homelessness in unsheltered locations, transitional housing and shelters known as point-in-time counts. However, data quality may be an issue, as the PBO explained that their report on urban, rural, and northern Indigenous housing was based on data provided by government departments but that “getting accurate, high-quality data proved to be a challenge.”[200] This was not because federal departments were not willing to provide it, but rather that “the quality of the data itself was not what we would have expected.”[201] The data also did not provide enough regional detail and was dated as the housing market and population growth may mean that 2016 census data does not reflect the housing situation for Indigenous peoples in 2020.[202]

However as explained in a brief, current government data such as the census may not accurately represent Indigenous peoples.[203] Some witnesses highlighted the need for better data[204] related to Indigenous housing and identified specific data gaps in Indigenous housing in Winnipeg,[205] and more generally, in estimating the number of people experiencing hidden homelessness.[206] One witness also pointed out that Indigenous youth, women and 2SLGBTQQIA communities are often not counted in point-in-time counts.[207]

The lack of accurate and standardized data is a barrier towards the development and sustainability of community housing for Indigenous peoples. It may underrepresent the size and composition of Indigenous populations across Canada leading to lower estimates of community need.[208] As discussed later in this report, witnesses identified how housing leads to savings and benefits, yet some indigenous communities feel these are underestimated in current data.[209]

The Committee heard that data sovereignty including data collection by and for Indigenous peoples is a component of Indigenous-led housing solutions.[210] One witness explained that housing needs are currently assessed based on models that are often not designed by Indigenous communities.[211] For example, in the Territories, the Committee heard that models to assess housing needs are developed and defined by the territorial government, which makes it difficult for communities to identify their housing needs and where they need to be prioritized.[212]

In London, Ontario, the Committee heard that data gathering primarily happens through street outreach with individuals experiencing homelessness. However, one witness explained hearing frequent feedback that individuals are being asked about their identity in a manner that is not culturally safe.[213] Ultimately, as Andrea Jibb, Director of Community Planning for Atlohsa Family Healing Services explained: “We're not going to get good data on Indigenous homelessness unless it's coming from that relationship-focused approach in which somebody feels safe to talk about their identity with an outreach worker.”[214]

The Committee heard examples of First Nations-led data collection. For example, the Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador has been collecting data on housing in First Nations on-reserve communities in Quebec since 2000 that is updated every four years.[215] Further, Indigenous Services Canada is currently working with the Assembly of First Nations and CMHC on a 10-year First Nations housing and related infrastructure strategy. To inform its development and implementation, First Nations-owned data and information is being gathered by First Nations.[216]

Witnesses identified ways to improve data collection to measure current and future housing needs and gaps. The Ontario Non-Profit Housing Association recommended the development of a community-supported Indigenous housing database.[217] The National Alliance to End Rural and Remote Homelessness recommended creating a federal data strategy for rural and remote communities that includes a federal count of individuals experiencing homelessness.[218] Federal departments may also be working towards ensuring Indigenous peoples are identifying their own housing needs and gaps. CMHC also told the Committee that it will “be working with Indigenous partners, housing providers and others to identify critical housing needs and gaps in urban, rural and northern areas. This work will complement a larger plan to address critical infrastructure needs in Indigenous communities.”[219]

Together, the Committee recognizes that data collection plays an essential role in Indigenous-led solutions. To ensure that data meets the needs and priorities of communities and is ethically collected, the Committee believes more work is needed to support Indigenous-led data collection.

Wrap-around Services

Housing is more than just bricks and mortar. While housing provides a roof over one’s head, it does not provide wrap-around services. Witnesses told the Committee that housing must include the provision of culturally appropriate, trauma-informed wrap-around services in areas such as health and mental health, parenting support, employment, education/training, life skills and healing.[220]

As explained in a brief submitted to the Committee, wrap-around supports that recognize and reflect the diversity of community needs are important to “address the lasting impacts of racism, colonialism, and intergenerational trauma.”[221] Ms. Jibb told the Committee that “[t]he history of colonization has displaced Indigenous peoples from the land and from our communities, and wraparound supports thus provide the relationships and the trust to keep people feeling safe in their homes.”[222]

“You're not going to be able to live a healthy life and get a house and do anything like that if you don't heal what is harming you.”[223]

Wrap-around supports provide critical programming to help individuals keep housing while supporting their well-being and long-term success.[224] They can also support Indigenous peoples to improve health, education, and employment outcomes while reducing overrepresentation in the health, justice, and social services systems.[225] Ms. Johnston drew on her organization’s experience to emphasize the importance of wrap-around supports:

“having the supports in place to allow people who are chronically homeless and have mental health or addiction issues to live independently takes those wraparound services. When those are not available, when we put people in individual units out in the suburbs with no supports, that does not respond to the question of homelessness, or to the need for housing in any way, shape, or form.”[226]

According to one witness, wrap-around services should support individuals experiencing homelessness to maintain connections to friends and family.[227] They also help individuals who have experienced homelessness for several years to build important life skills such as budgeting, paying their rent or visiting a grocery store. As explained by Ms. Jibb, sometimes individuals have experienced so much trauma that they do not feel safe going into the community by themselves and require support from staff.[228] Wrap-around supports must be adapted to meet the needs and preferences of Indigenous peoples, which could include for example 24-hour intervention support for addiction and mental health issues.[229]

“[F]rom a mental health lens, it is also about safety. It's also about recognizing the trauma community members have faced. What contributes to our own experience of safety can vary. I think that's where, when we talk about culture, we are talking about many aspects of what we may think about in terms of culture. We provide training and support for land-based cultural experiences but also, just more deeply and richly, there is that idea of trauma, the impact of trauma and the importance of safety and how we create safety when we're supporting people, being really tangible and directly related to mental health.”[230]

Ultimately, wrap-around services must be culturally appropriate, and trauma informed. Generally, programs and services that integrate culture may lead to better outcomes for Indigenous participants. Damon Johnston, President of the Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg, explained the impact of culturally appropriate approaches to service delivery in Winnipeg:

“they're [the approaches are] culturally competent; they recognize each individual, whether they're Dene, Ojibwe, Anishinabe, Ininew or Cree, Michif or Métis. You're recognizing each person for their cultural uniqueness, and then you're working with them to create programs and services that work with them. You can bring other individuals who are part of their communities into the picture to help develop these newer, innovative approaches to trying to ensure that with the investment you're making in treatment, in housing, in other supports, you're going to have a longer-lasting outcome.”[231]

While the Committee heard that Indigenous peoples prefer to access services or supports provided by Indigenous peoples,[232] these may not be available in all communities across Canada. Where services are unavailable, Indigenous peoples may choose to access non-Indigenous specific services. However, Indigenous peoples may face barriers to accessing them, as Ms. Hache told the Committee:

We've had, for example, Indigenous women who have had to talk into a box outside to get into a shelter and they haven't been allowed into the shelter because there was an assumption that they had been drinking. Because of that, they have gone back home.[233]

Without access to culturally appropriate services, Indigenous peoples may avoid accessing support altogether,[234] which may have significant consequences for their health and well-being. In Montreal, many Indigenous peoples living on the streets mistrust the mainstream healthcare system and may refuse to seek medical care to the detriment of their own health, and in some cases their lives.[235] Lack of access to culturally-appropriate programming can be particularly challenging for Indigenous seniors. Marcel Lawson-Swain, Chief Executive Officer of the Lu’ma Native Housing Society shared the experience of his mother-in-law: “She was in residential school, and because she is not in a special seniors program for Indigenous people, she finds herself in a place where she feels like she's back at residential school again. So she starts her life out that way and she has to end her life that way.”[236]

Building Community

Housing, which is “about giving a sense of home…[and] belonging,”[237] can support the development of vibrant Indigenous communities in urban areas across Canada. However, the Committee heard that the way housing is provided in Montreal does not foster a sense of community and does not meet the needs of Indigenous peoples. In Montreal, housing programs for those who are homeless generally involve solitary living arrangements outside the downtown core and far away from the community that homeless individuals have built in the city. As explained by one witness, Indigenous peoples don’t often cope well with these arrangements and leave stable housing to return to live within a street community. The Committee heard that: “Housing options need to be in urban areas where Indigenous people congregate. They need to include both private and communal spaces, where people can benefit from privacy, but also friendship, connectedness, and community.”[238]

Housing can also support Indigenous peoples to reclaim their connection to their traditional lands and communities within urban spaces. For example, Mr. Eddy described the connection between the name of two buildings developed by his organization and First Nations use of the land:

“One was called Skwachàys and the other Kwayastut and those names were given to us by Chief Ian Campbell of the Squamish Nation. Skwachàys was the name of the area pre-contact in Vancouver and the folks from the north shore used to canoe over to the Skwachàys, which was an area of salt marshes. There was a lot of great hunting and fishing in the area. Up through the salt marshes were underground springs, and those springs were regarded as portals to the spirit realm. It was described as a place of transformation as well. The name fit perfectly with what our purposes were and what we developed as a theme which we call ‘community building through the transformative power of art’…Kwayastut, the chief told us, means ‘finding one’s power’. It was again very appropriate for the Indigenous youth who were in the building.”[239]

Taken together, as explained by one witness, housing should support Indigenous peoples to be part of a community and find healing with other Indigenous peoples.[240]

Best Practices

The Committee heard several examples of Indigenous organizations providing Indigenous-led, culture-based, trauma-informed housing programs with wrap-around supports. These initiatives respond to priorities identified by the community, support positive outcomes, and encouraged partnerships. For example, Atlohsa Family Healing Services is a non-profit organization with over three decades of experience working with urban Indigenous peoples in southwestern Ontario. It provides an emergency shelter, a low barrier shelter for Indigenous people experiencing homelessness, and other services. In 2020, Atlohsa Family Healing Services launched a strategic plan to address homelessness in the community known as the Giwetashkad Indigenous Homelessness Plan. The Plan is based on Indigenous definitions of homelessness and the lived experience of Indigenous people experiencing homelessness in the community.[241]

In many cases, housing and wrap-around supports led to positive outcomes for Indigenous peoples and communities. For example, as discussed previously, Friendship Centres are hubs providing a number of culture-based services including housing in cities and towns across Canada. Friendship Centres offer a significant range of culture-based services delivered alongside or parallel to housing, which “obtain far better outcomes over the long-term for a variety of intersecting issues.”[242]

An initiative in Sioux Lookout, Ontario led 20 Indigenous people who had been chronically homeless to receive much-needed culture-based supports.[243] The initiative involved a number of organizations: the Nishnawbe-Gamik Friendship Centre in Sioux Lookout came to an agreement with the Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services Corporation and the district social service administration board. Each partner played a role in the initiative. The Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services Corporation built the housing, the service manager provided the land and the Friendship Centre provided culturally appropriate supports.[244] Mr. Wall explained how the program impacted participants: “We found that the transformation in the 20 individuals who were provided housing was incredible. We're talking about individuals who have lived on the streets for decades, who communities have written off, but are now looking at being enrolled in employment programs and are looking at access to jobs.”[245]

Another example is AHMA which is “Canada’s first Indigenous grassroots housing authority” of 41 Indigenous housing providers “created for Indigenous people by Indigenous people.”[246] As explained in a brief, “AHMA is working with its communities to reclaim self-determination through culturally appropriate housing that honors Indigenous traditions in meaningful ways.”[247] AHMA’s members provide families with culturally appropriate and affordable housing in addition to support services in areas such as homelessness prevention, parenting skills, transition homes and mental health programs among others.[248] According to a reference document received by the Committee, “AHMA’s programs and services have created opportunities for individuals to overcome barriers such as homelessness, substance abuse, mental health issues, discrimination and systemic racism.”[249]

The Committee also heard about the work of several Indigenous organizations. For example, the Namerind Housing Corporation is an Indigenous non-profit housing provider whose mission is to “provide safe and affordable quality housing and economic development opportunities for Indigenous people in Regina,” Saskatchewan.[250] As explained by the Corporation’s president and chief executive officer, it creates jobs, wealth, and a sense of ownership of housing in Regina.[251]

Organizations are also developing different types of housing to support Indigenous peoples. For example, the Committee heard about Indigenous co-operative housing such as the Four Feathers Housing Co-operative in London, Ontario that housed mostly seniors and people over 40.[252] Generally co-operative housing can provide affordable housing, owned and managed by community members who live there.[253] One witness shared general comments about the importance of housing co-operatives:

“I believe that housing co-ops provide a safe family environment for members, especially women, to embrace their culture and community, develop and maintain self-respect, respect and fulfill their land stewardship responsibilities for Mother Earth, find employment, access higher education, and nurture the seeds for future generations.”[254]

Co-operatives can also provide support for those with disabilities. As explained by Tina Stevens, President of the Co-operative Housing Federation of Canada, assistive devices and equipment are high priorities to ensure that people with disabilities “can continue to live their lives as close to normal as possible, as well as to sit with their families, to reconnect with their communities and to function normally on a daily basis as well as possible.”[255]