FOPO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

PACIFIC SALMON: ENSURING THE LONG-TERM HEALTH OF WILD POPULATIONS AND ASSOCIATED FISHERIES

Introduction

Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) are some of the most iconic fish in Canada and are woven into the cultural traditions of First Nations in British Columbia (B.C.) and Yukon.[1] They provide a range of cultural, socio-economic, and environmental benefits to the region. Pacific salmon abundance levels are significantly correlated with the health and productivity of many plant and animal species, such as the Southern Resident killer whales.[2] Between 2012 and 2015, commercial and sport Pacific salmon fisheries contributed an average of over $1 billion in gross domestic product and 12,400 full-time jobs to the Canadian economy.[3]

Given the substantial abundance declines of many wild Pacific salmon populations in B.C. since the early 1990s, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans (the committee) decided to undertake a “study on the state of Pacific salmon and make recommendations on the next steps to ensure the long-term health of these stocks, as well as the commercial, Indigenous and recreational fisheries that depend on them.”[4]

The committee held 16 meetings between 10 March 2020 and 2 June 2021, during which it heard testimony from First Nations, commercial and sport fishing associations, fishery scientists, academics, environmental non-governmental organizations, seafood processing companies, and a salmon aquaculture association.

The committee also received the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans, and the Canadian Coast Guard, Bernadette Jordan, accompanied by officials from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). Members would like to extend their thanks to all the witnesses who participated in this study. The committee is pleased to present the results of its study in this report, along with recommendations based on the evidence it heard.

Background

About the Pacific Salmon

Pacific salmon mature in the ocean before undertaking a migration to reproduce in freshwater environments. Adults return to their natal streams to reproduce by tracing chemical signatures of these waterways.[5] Pacific salmon are also semelparous, meaning that adults die after reproduction and become nutrients and food in freshwater streams. Pacific salmon, therefore, only reproduce once in their lifetime.

Species Managed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

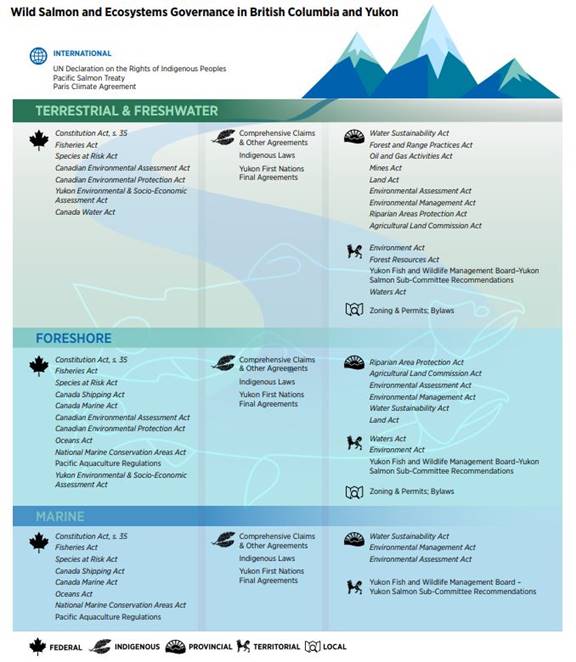

Given their migratory nature, Pacific salmon populations are affected by natural and anthropogenic pressures, resulting from management decisions made at the international, federal, Indigenous, provincial/territorial, and municipal levels (Figure 1).

Figure 1—Pacific Salmon and Ecosystems Governance

Source: DFO, Wild Salmon Policy 2018 to 2022 Implementation Plan.

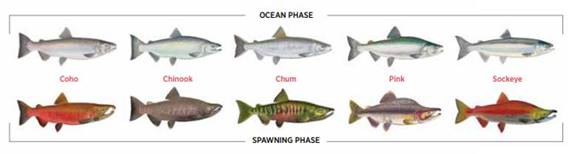

At the federal level, DFO manages five species of Pacific salmon in B.C. and Yukon (Figure 2), which are: chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum (Oncorhynchus keta), coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch), pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) and sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka).[6]

Figure 2—Pacific Salmon Species Managed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Source: DFO, Wild Salmon Policy 2018 to 2022 Implementation Plan.

Pacific salmon are managed by DFO according to Canada’s Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon (commonly referred to as the Wild Salmon Policy or WSP), released in 2005.[7] The goal of the WSP is to restore and maintain healthy and diverse salmon populations and their habitats. Conservation of wild salmon is the highest priority for federal resource management decision-making while respecting Canada’s obligations to First Nations.

Under the WSP, salmon productivity and diversity are managed at the level of the Conservation Unit (CU).[8] There is a total of 432 CUs in B.C. A CU is a population of wild salmon sufficiently isolated from other groups that, if lost, is very unlikely to recolonize naturally. Therefore, the monitoring of spawning streams and annual estimates of fish returning to spawn (escapement) represent critical activities to be undertaken by DFO to effectively implement the WSP. Setting escapement targets for returning wild salmon requires fisheries managers to accurately forecast the size and timing of salmon runs.

Wild Pacific Salmon Abundance Trends

Over the past 20 years, more than 20 federal and provincial inquiries have investigated declines in wild Pacific salmon populations and associated fisheries.[9] These inquests, including the 2012 Cohen Commission,[10] have resulted in over 200 recommendations and cost millions of dollars to conduct. Despite this effort, according to the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), there are currently 39 populations of chinook, coho and sockeye salmon at risk (classified as Special Concern, Threatened or Endangered) in B.C.[11]

Salmon abundance trends vary along a north-south gradient, where northern populations (those that enter the ocean above the northern tip of Vancouver Island) are generally doing better than their southern counterparts.[12] Chinook numbers are declining throughout their B.C. and Yukon range, and sockeye and coho numbers are declining, particularly at southern latitudes. Salmon that spend less time in freshwater, such as pink and chum, are generally not exhibiting long-term declines but DFO deems the data quality to be low.

State of Pacific Salmon

North Pacific Range

According to Richard Beamish, Scientist Emeritus at DFO’s Pacific Biological Station in Nanaimo, B.C., and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, there is an international Pacific salmon emergency.[13] He indicated:

There were unprecedented declines in Pacific salmon abundances throughout the entire North Pacific in 2020. The total commercial catch by all countries was the lowest in 30 years. The total catch of all species was 605,000 metric tons and that's a 38% decrease from the average for the past decade.

In British Columbia, the total commercial catch in 2019 and 2020 was the lowest in history. The average for both years was 5,200 metric tons which is just 7.5% of the average annual catches in the 1970s. The unexpected poor catches in 2019 and 2020 extended north throughout all southeast Alaska. The total abundances of sockeye salmon produced in the Fraser River were the lowest in history in 2019 and 2020.

Fraser River System

The Fraser River system, the largest on Canada’s West Coast and historically among the greatest salmon producing rivers in the world, has seen extremely low chinook and sockeye returns in 2019 and 2020, with significant fisheries closures. Darren Haskell, President, Fraser Salmon Management Council, described the local situation as follows:

With the early 2019 Stuart return, we only had 89 sockeye return, out of a brood year of 10,096. That's 1% of that brood year 2015. The early summer aggregate was only 33% of the 2015 brood year, and within that aggregate, the Bowron River run had only 20 sockeye return out of a brood year of 3,868. That's less than 1% of a return.

The summer run aggregate is 25% of the brood year. The largest run, usually in the summer, is the Chilko run. That run had 168,000 return. That sounds like a lot, but not when you compare it with the expected return of over 600,000, which is 25% of the brood year.

With our chinook for 2019, we're facing, for the upper and middle Fraser River spring chinook, an 85% to 90% loss of the run, and a 50% loss for the mid-Fraser summer chinook.[14]

Dustin Snyder, Director of Stock Rebuilding Programs, Spruce City Wildlife Association, pointed out that some populations, only known to exist by certain people, in the upper Fraser have already disappeared.[15]

During its study, the committee also heard evidence regarding the Interior Fraser steelhead (Oncorhynchus mykiss), in particular the Thompson and Chilcotin populations, a species sharing the same environment with the Pacific salmon. Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, described the situation of the steelhead in the Fraser River system in this way:

The trouble is that these fish comigrate with pink and chum salmon, and in the worst years, steelhead experts estimate that half of these fish were caught in a net as bycatch, and up to half of those died. Populations were considered in severe decline in the mid‑1990s, when 3,000 to 4,000 spawners made it. There were an estimated 62 Thompson and 134 Chilcotin fish this year. They're endangered.[16]

Recommendation 1

That, wherever possible, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, in collaboration with all interested parties, including Indigenous governing bodies and the Province of British Columbia, harmonize efforts to conserve and restore steelhead with efforts to restore Pacific salmon stocks of concern.

Key Factors Affecting Salmon Abundance

Pacific salmon abundance is affected by the cumulative impact of several factors. Brian Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, illustrated the path of the Fraser River sockeye from spawning areas to the ocean through the estuarine migration corridor as follows:

I think the Fraser sockeye also exemplifies the difficulty of understanding the causes of the state of salmon. Fraser sockeye salmon rear in the streams and lakes of the Fraser drainage. They go through a highly disrupted estuary in the city of Vancouver and peripheral areas. They then spend two to three months in the Strait of Georgia, which is what we call the “near shore”. They go past the Discovery Islands, which are obviously in the media frequently because of the state of the open net-pen salmon farms and their transition. Then they go out to sea for two years and return.[17]

Warming Ocean Conditions

Warming ocean temperatures have negative impacts on the marine survival and growth of salmon through effects on prey species and plankton communities at the base of food webs. Brian Riddell explained that the magnitude of impacts on different salmon species depends on the length of their stay in the ocean and life histories:

These are strong environmental trends that are causing the decline, particularly of things like Fraser sockeye salmon. One of the reasons we're seeing differences in different stocks of salmon and different species is that they don't all use the ocean in the same way.[18]

Regarding herring, a forage fish vital to the salmon’s diet, Frank Brown, Senior Advisor, Indigenous Leadership Initiative, indicated:

If you look at what's going on in British Columbia with herring, it's very similar to salmon. The herring have collapsed on Haida Gwaii. The north coast is in jeopardy. The gulf is questionable. There are no more herring on the west coast of Vancouver Island, which is the main food for both salmon and the orca.[19]

Noting recent significant declines in salmon catches in Japan and Russia despite large-scale hatchery programs taking place there, Richard Beamish called for increased international scientific cooperation to better understand the mechanisms that regulate salmon survival in the deep-sea environment. Within the federal government, as Brian Riddell mentioned, scientific collaboration is also lacking between DFO, Environment and Climate Change Canada, and Natural Resources Canada.[20]

Recommendation 2

That, as climate change continues to have significant impacts on ocean temperatures, Fisheries and Oceans Canada work in collaboration with Environment and Climate Change Canada to expand research and gather more data on how changes to the deep-sea environment is impacting the survivability of wild salmon.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Freshwater and estuarine habitat loss and degradation have been linked to cumulative effects of residential, industrial, and agricultural development, including flood mitigation measures.[21] In Marvin Rosenau’s opinion, there has been a “spectacular failure to protect large amounts of salmon habitat in recent years regarding the removal of flood-land forests in order to develop farmland in the areas between Mission and Hope on the lower Fraser River in B.C.”[22] He pointed out that many pump stations preventing flooding are old and decrepit, and progress has been slow on upgrades to make them fish‑friendlier.

In Brian Riddell’s view, all habitats are interconnected. He mentioned the vital need for conservation and restoration of estuarine habitats “where salmon have to spend up to about a month and where they adjust to salt water and continue to grow before moving out to sea.”[23] Regarding the Port of Vancouver’s proposed expansion of the Terminal 2 project on Robert Banks in the Fraser estuary, Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary for Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, suggested that the federal and provincial governments, First Nations and municipalities should consider co‑developing an estuary management strategy to assess cumulative effects on salmon habitat.[24]

DFO’s capacity to coordinate and manage effective habitat restoration was, however, questioned by Jesse Zeman. He stated:

In terms of freshwater habitat restoration, DFO's restoration unit has 16 positions for the entire province of British Columbia, and half of those are currently vacant. The projects it deals with are often proponent-driven and at a scale that is not meaningful for salmon. The restoration unit has no base budget. The restoration unit needs to be adequately staffed and funded and given the ability to plan at a watershed scale that is meaningful for salmon.[25]

In the opinion of Josh Temple, Executive Director, Coastal Restoration Society, habitat restoration work represents a great opportunity to create meaningful employment opportunities for First Nations and coastal communities in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic and declining salmon fisheries.[26] He added that “regional management is critical because of the diversity of habitats and unique situations that each habitat and watershed faces” and, given the depth of local knowledge, a collaborative regional approach is key.

Failure from DFO to enforce habitat protection was also an issue raised by witnesses. In Marvin Rosenau’s view, many activities involving the removal of flood-land forests to develop farmland in the Lower Fraser area have been “clear” violations of the fish habitat provisions of the Fisheries Act. He added that DFO has not charged any landowners under the Act, and up to a thousand hectares of prime Fraser River juvenile salmon-rearing habitat have been or will be lost because of inadequate enforcement or bad triage decision-making by DFO’s Fish and Fish Habitat Protection Program.[27]

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia, First Nations, and local governments co‑assess the cumulative impact of residential, industrial and agricultural developments in the lower Fraser River on wild salmon stocks and develop a strategy to protect, preserve and restore those stocks, and develop a framework for the assessment of proposed new developments that includes cumulative impacts.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada, the Province of British Columbia and, where appropriate, First Nation communities review the state of flood control/mitigation systems along the lower Fraser River and their impact on wild salmon, and co-develop a program to update pumping stations and other components, as necessary, to remove risks to wild salmon runs.

Recommendation 5

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada develop and implement an estuary management strategy to preserve salmon habitat.

Recommendation 6

That, in recognition of the depth of knowledge found in local regions, Fisheries and Oceans Canada move towards a collaborative regional approach to assess priorities, develop and implement management strategies for the long-term sustainability of habitats and wildlife, and enable regional management of local marine environments and individual watersheds.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada prioritize coastal restoration work in British Columbia as part of the COVID-19 job recovery, and that this include meaningful employment opportunities and contract work for First Nations and coastal communities as a critical part of rebuilding coastal economies.

Open-Net Pen Salmon Aquaculture

The effects of open net-pen Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) aquaculture on wild Pacific salmon populations represent not only an environmental concern but may also have economic implications for commercial and sport fisheries. Echoing the Cohen Commission’s observation that DFO’s promotion of open net-pen farmed salmon conflicts with its mandate to protect wild fish, Karen Wristen, Executive Director, Living Oceans Society, indicated that Agriculture and Agri‑Food Canada is “well placed to do that marketing and promotion. DFO needs to be instructed that its primary mandate is the restoration of wild salmon.”[28] Her view was also shared by Kathy Scarfo, President, West Coast Trollers Association.[29]

The integrity of DFO’s science advisory process, and data transparency regarding risks of disease and pest transfers from farmed salmon to wild fish were mentioned by several witnesses as an issue. In the view of John Paul Fraser, Executive Director, BC Salmon Farmers Association, “scientific integrity and transparency are important in advancing the dialogue and dispelling the uncertainties around wild and farmed salmon interactions.”[30] However, Aaron Hill, Executive Director, Watershed Watch Salmon Society, indicated that DFO has shortcomings in this regard:

There is a tremendous lack of accountability and transparency within the department and, as I mentioned, a disconnect between the priority in the wild salmon policy of putting conservation first and what we actually see in terms of decisions around fisheries management, habitat, salmon farms and other things.[31]

Robert Chamberlin, Chairman, First Nation Wild Salmon Alliance, added:

Proponents—in this case, a fish farm company and fish farm industry associations—are involved in every component, every step, of determining if the operations pose a risk to Pacific salmon, such as the steering committee developing the scope of the science, terms of reference, and discussion paper development, and the peer review itself can be unduly influenced by industry, as they can select who will participate in the peer review.[32]

The committee also heard Kristi Miller‑Saunders, a research scientist at DFO, reiterating her 2016 statement calling for DFO research to understand open-net salmon aquaculture impacts on wild stocks to be transparent, objective, and independent of influence from industry.[33] Furthermore, members were informed that certain scientific findings regarding Tenacibaculum maritimum causing mouth rot disease in wild salmon migrating past Discovery Islands farms were not shared with First Nations and it was unclear if the Minister was briefed.[34]

To better understand how infectious agents can affect the health of wild salmon, DFO is collaborating with the Pacific Salmon Foundation and Genome BC on a multi-year, four-phase Strategic Salmon Health Initiative (SSHI). Brian Riddell noted, however, that Phase 3 has been unable to proceed due to the lack of a facility to perform disease challenge studies on understudied agents considered to be the most impactful from Phase 2.[35]

As the federal government has taken the decision to phase out existing salmon farming facilities in the Discovery Islands, members examined the issue of remediation of the seabed beneath these farms to remove accumulated organic waste. According to Emiliano di Cicco, Fish Health Researcher, Pacific Salmon Foundation, it may take months for the seabed to recover naturally.[36] Further research may be required to study the time needed for the full recovery when sites are left to fallow.

Phasing out salmon farms in the Discovery Islands can also economically impact communities who depend on them. Therefore, the committee heard Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary for Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, calling for the federal government to ensure that its plan to transition from open net-pen salmon farming in coastal B.C. waters by 2025 includes economic support for affected communities.[37]

Recommendation 8

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada study the seabed under and near open-net aquaculture operations to determine if remediation will be necessary when those operations close.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada recognize that the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard cannot both protect wild salmon and promote the aquaculture industry, and remove the promotion of aquaculture from the mandate of the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard.

Recommendation 10

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada improve its data transparency practices, including making information available to the public without needing approval from industry and corporate stakeholders.

Recommendation 11

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada ensure that Phase 3 of the Strategic Salmon Health Initiative is properly funded. In addition, the Initiative should be provided an adequate facility to perform the critical challenge studies required to assess the findings of Phase 2’s molecular studies, which will help inform and streamline the department’s response to the decline of wild salmon populations.

Fishing Pressure and Illegal Catch

Over the years, DFO has introduced various restrictions on fisheries to conserve wild stocks. Even First Nation food, social and ceremonial fisheries, which have a constitutionally protected priority, have experienced restrictions as a result of conservation efforts.[38] According to DFO’s precautionary approach, to reduce by-catch risks to less productive populations, “in mixed-stock and multispecies fisheries, management actions to rebuild a depleted stock may require restrictions on fishing opportunities for other stocks and species whose populations are healthy.”[39]

Given the effects of the Big Bar landslide exacerbating the poor state of many Fraser salmon populations, Darren Haskell recommended decreasing efforts across all fisheries. However, DFO’s focus on restricting harvest opportunities as the primary tool to conserve weak stocks was criticized by Robert Hauknes, a commercial fisher.[40] Jesse Zeman also panned DFO’s excessive focus on fishery restrictions while failing to take into account data and information from outside the department:

DFO is culturally and structurally broken. It is a fishing management agency. It's not accountable to the public. Getting data from them is almost impossible. We are constantly referred to ATIP because people are worried they will lose their job if they share data with the public that was paid for by the public. Scientists, habitat staff and enforcement staff are rarely listened to. The prescription of the day is fishing, fishing, fishing.[41]

To reduce by-catch in mixed-stock fisheries, Jesse Zeman called for DFO to assist fishers in the transition away from non-selective gear harvesting. He pointed out that applications from certain First Nations to the British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund (BCSRIF) to that effect were turned down by DFO.[42] The committee observes that, as far back as 2009, a report prepared for the Pacific Fisheries Resource Conservation Council recommended DFO “transfer the allowable catch to more terminal areas, including into rivers of distinct stock origin,” and “fully implement and enforce the use of proven selective fishing methods.”[43]

Kathy Scarfo summarized the dire state of B.C.’s commercial salmon fisheries and fishing communities as follows:

If we are looking at solutions to moving forward, the first thing to do is to recognize that the situation in British Columbia is a disaster, and we need that disaster relief. We need somebody to call it for what it is, and it is a disaster: 90% of the fleet is not going to survive; they're being forced into bankruptcy.[44]

The sport fishing sector has also experienced access and retention restrictions with distressing consequences to coastal economies. Owen Bird, Executive Director, Sport Fishing Institute of British Columbia, argued:

While reductions to access and harvest have now reached the lowest levels possible and in some cases eliminated opportunity entirely, evidence shows that continual ratcheting down of this source of mortality alone is insufficient to positively effect change in the productivity and abundance of salmon stocks of concern.[45]

Concerns regarding illegal fishing and the failure of DFO enforcement to take forceful action have been expressed by some witnesses. Jesse Zeman stated:

On poaching, there are pictures of endangered chinook and steelhead and at-risk coho in illegal nets that surface almost daily. They are reported to DFO, and no one even calls us back. Charges are rarely pursued. Fisheries officers have become experts in cutting gillnets out of the Fraser, as opposed to protecting salmon from poachers.[46]

Recommendation 12

That, without prejudice to Aboriginal and treaty rights, wherever possible, Fisheries and Oceans Canada promote alternatives to non-selective fishing in waters where at-risk salmon runs are present.

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada work with stakeholders, First Nations, and local communities to restore salmon habitat, and strengthen the monitoring and guardianship of salmon stocks to help discourage illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing.

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada recognize that the situation in British Columbia facing fish harvesters is urgent, and that relief will be necessary to support commercial, recreational, and Indigenous harvesters as these communities rebuild the fisheries.

Predation from Increasing Pinniped Populations

In the view of Carl Walters, Professor Emeritus at the University of British Columbia, wild salmon declines have “substantially been due to massive increases in marine mammal, seal and sea lion populations and their predation impacts.”[47] He explained:

None of us suspected that marine mammals might be a cause of these declines until a major paper came out from DFO scientists in 2010 showing that the seal populations in the Georgia Strait had increased by about tenfold between 1972 and 2000 in a pattern that was pretty much a mirror image of the decline in the Georgia Strait sport fishery.

Our data show that the amount of juvenile salmon eaten by seals each year in the Georgia Strait is enough to directly account for the decline. There are almost as many juvenile chinook and coho going into the Georgia Strait every year as juveniles as there were back in the 1970s, but they're not surviving their first year in the ocean.

The committee heard that the Pacific Balance Pinniped Society submitted proposals to DFO for commercial and First Nation harvesting of seals and sea lions, aimed at reducing these pinniped populations to about 50% of their current levels over three years.[48] According to Andrew Thomson, Regional Director at DFO, the department is still assessing these proposals and there is a need to fully understand ecosystem impacts before authorizing a new fishery.[49]

Recalling its 2016 Atlantic salmon and 2017 northern cod studies, the committee recognizes the need for comprehensive predation studies. However, members also believe that pinniped predation represents a growing concern in localized areas, such as estuaries and migration corridors. To date, DFO has done little to mitigate predation impact, shying away from this issue for too long.

Recommendation 15

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada examine and consult with stakeholders and the public at large on the impact of predators, including pinnipeds, on wild salmon runs and, on a strategy, to manage predators of concern. Such strategy should establish a mechanism to allow for the removal of habituated and nuisance pinnipeds that are impacting salmon enhancement or have an outsized impact on salmon survivability in migration corridors.

Role of Hatcheries

Public and Community Hatcheries

Among the programs developed by DFO to arrest the decline of wild Pacific salmon is the Salmonid Enhancement Program, first launched in 1977. The pillar of the program is funding for community conservation-focused hatcheries.[50] Witnesses, however, identified many shortcomings in the program, particularly with respect to strategic planning and funding; issues that became more apparent after the Big Bar landslide disrupted Fraser salmon passage. DFO itself highlighted this problem during its appearance before the committee, recommending that important investments must be made to establish hatchery facilities above the Big Bar landslide site on the Fraser River, noting that it is “a gap that has been in place forever, made worse by the slide and the pressure on those stocks.”[51]

Dave Hurwitz, Hatchery Manager, Thornton Creek Enhancement Society, explained that “[i]nflation and aging infrastructure threaten every hatchery's ability to undertake more salmon enhancement and more tagging and research, and our hatchery is not alone in this regard.”[52]

Aaron Hill, while expressing concerns regarding the genetic and food competition risks posed by reared salmon from hatcheries to wild salmon, potentially exacerbating the precarious situation of certain wild stocks, stated the view that DFO’s hatchery approach has been ad hoc and has failed to restore salmon runs of concern:

DFO's current risk assessment framework for hatcheries is piecemeal. It hasn't been peer-reviewed. It doesn't cover all the risk factors. It doesn't get applied to all hatchery operations and the process is not transparent. We do need a few hatcheries here and there in extreme cases like […] but the risks need to be properly assessed, with wild salmon health as the top priority.[53]

The committee notes that DFO’s Salmonid Enhancement Program includes guidelines to manage spawning and hatchery practices to maintain genetic diversity and minimize impacts on resident freshwater juveniles as described by the WSP. The WSP acknowledges that “hatchery practices may alter genetic diversity. Wild salmon may have to compete with enhanced salmon for food and space in the marine and freshwater environments.”[54]

Witnesses also cautioned against relying solely on hatcheries to restore salmon stocks, with Jason Hwang, Vice-President, Pacific Salmon Foundation, noting that “hatcheries are an important and appropriate tool, but they're not a magic silver bullet. You don't run out and build a hatchery every time you have a salmon problem.”[55]

Recommendation 16

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada, local organizations and First Nation communities co-develop and implement a hatchery strategy in alignment with the Wild Salmon Policy for the Fraser River watershed based on science, focusing on the best outcomes for existing wild salmon stocks or the need to restore runs that are extinct or can no longer sustain themselves naturally.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada immediately increase support for community-based hatcheries, who have not seen an increase in financial support for decades.

Commercial Hatcheries and S1 Smolts

The committee also heard about the potential role that commercial hatcheries can play in the recovery of salmon stocks. Carol Schmitt, President, Omega Pacific Hatchery Inc., lamented the perceived intransigence of DFO’s Salmonid Enhancement Program, stating:

[T]hey're continuing 44 years with their same strategy. Even with the results that we've shown that can make a huge difference. You can rebuild a stock in four years to over 1,500 fish, yet some of them have had five million fish released over 40 years and they're at almost the same number when they started 40 years ago.[56]

Carol Schmitt raised the idea of rearing S1 smolts[57] for a year in a hatchery environment, which are “much more physiologically developed, mentally developed and immune-developed” as a potential strategy in recovering stocks that the federal government should explore.[58] In her view, “rebuilding efforts have not increased the stocks because DFO's enhancement smolts released as S0s have low marine survivals and too few adult returns.”

The S1 smolts can also be successfully raised through the practice of sea penning. Dave Hurwitz explained that to “take the fry from the hatchery at five grams and put them in a sea pen at the mouth is very, very important for imprinting to that natal stream. In two weeks they double in size, and we have exponential survival.”[59]

The committee notes that it made a recommendation to DFO to expand “the Salmonid Enhancement Program to include hatcheries utilizing alternative methods of chinook production, including the rearing of S1 chinook” in its 2018 report on endangered whales.[60]

Recommendation 18

That the Government of Canada investigate the comparative data on the difference in survivability between S0 and S1 chinook smolts and consider how this can be applied to increase returns of stocks of concern.

The Potential of Mark-Selective Fisheries

Among other strategies, witnesses called for the implementation of mark-selective fisheries to protect wild stocks, while allowing for the harvest of some hatchery fish. Dave Hurwitz explained that:

[M]ass marking permits for selective fisheries that protect wild stocks while allowing for harvest of hatchery fish. It also provides hatcheries with the ability to ensure genetic integrity when spawning fish from small populations. Mass marking identifies the wildness of a run, allowing individual watersheds to be enhanced to their optimum.[61]

Owen Bird noted that implementing mark-selective fisheries for chinook in parts of Georgia Strait and Strait of Juan de Fuca, at times when high mark rates are combined with low prevalence of stocks of concern, can achieve the balance between providing socio-economic opportunities while at the same time minimizing impact on the recovery potential of stocks of concern.[62]

To reach this, Owen Bird recommended the incorporation of plans for mass-marking of chinook and coho salmon hatchery production into DFO’s Salmonid Enhancement Program and Integrated Fisheries Management Plans.[63]

Kristi Miller‑Saunders agreed that it would be helpful for research purposes, if all chinook and coho salmon released from hatcheries would be marked. She further explained that: “having mark-selective fisheries for hatchery fish would mean that we would have less fishing pressure on our wild fish, so if there are enough fish to be exploited, then the exploited fish are not our wild stocks.”[64]

In her appearance before the committee, Minister Jordan emphasized that she was not averse to a mark-selective fishery, and furthermore stated that DFO is “developing a framework on whether chinook marked selective fisheries and mass marking can be applied as a management tool,” with a pilot project planned for 2021.[65]

Recommendation 19

That the Government of Canada develop a comprehensive hatchery strategy which includes augmenting runs of critical concern, encouraging community hatchery programs where appropriate, and the implementation of appropriate mass-marking of hatchery fish.

Recommendation 20

That the Government of Canada implement a hybrid chinook fishery to allow for the retention of chinook salmon that are marked, or that are caught in established zones where stocks of concern are not present.

Empowering Indigenous Communities and Use of Indigenous Knowledge

Witnesses agreed that First Nations play a critical role in salmon conservation. Greg Witzky, Operations Manager, Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat, called for establishing permanent A-base funding support to First Nation fisheries organizations, such as his, to foster effective co-development and co-implementation of the decision-making and administrative processes with DFO and implement the department’s reconciliation strategy.[66]

In Greg Witzky’s view, DFO’s failure to properly resource Indigenous fisheries organizations “stops First Nations from fully participating in our rightful roles to protect the resources for everybody, not just for First Nations, but for children of fishermen who angle, commercial fishermen, bears, [and] eagles.”[67]

Further, witnesses such as Larry Johnson, President, Nuu‑chah‑nulth Seafood Limited Partnership, looked to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) for inspiration for self-determining their own blue economies, explaining:

First Nations can also provide advice and examples of how to breathe life into UNDRIP in a meaningful way for First Nations. Let First Nations help governments define UNDRIP through economic development.[68]

Arthur Adolph, Director of Operations, St’át’imc Chiefs Council, spoke of the implementation of UNDRIP as a restoration of Indigenous traditional knowledge to the decision‑making process on Pacific salmon conservation:

Basically, if we really want to take a look at reconciliation and implementation of UNDRIP, we need to take a step back and look at where we actually went wrong in regard to the management of land and resources. What was missing was our traditional and ecological knowledge, because for over 15,000 years we had the land and resources that sustained us for generations and generations. It just started collapsing within the last 150 years, so we need to incorporate that, led by Indigenous people.[69]

In Robert Chamberlin’s opinion, the principles of free, prior, and informed consent, consistent with UNDRIP, should be part of DFO’s consultation and accommodation process with regards to wild salmon. He stated:

This current government is beginning to set a table for the implementation of the United Nations declaration, and free, prior, and informed consent must be a foundational component, especially to the current Discovery Islands fish farm consultations and accommodations process; to embrace the details that have been provided by the First Nations involved in this consultation to meaningfully implement the precautionary principle, especially given that none of the Fraser River First Nations were included in the consultations that will further impact their Aboriginal rights.[70]

Greg Witzky called for DFO to recognize the decision-making authorities of First Nations for them to play a meaningful and effective role in the conservation and management of salmon. He indicated:

Many Indigenous peoples in these contemporary times now have the skills and capacity to effectively co-manage salmon fisheries alongside our DFO counterparts. What we don't have with those rights and capacities are the same levels of funding, jurisdiction and decision-making authorities that our partners in the different government departments possess. Meanwhile, Indigenous people are anticipated to play an instrumental role in the protection, management and preservation of Pacific salmon, so steps must be taken to embed this responsibility into the policies, regulations and laws that impact Pacific salmon throughout their life cycle.[71]

The committee also heard testimony in support of the development of a National Indigenous Guardians Network to ensure that First Nations in B.C. have the capacity to collaborate with Indigenous organizations from Alaska to Oregon on wild Pacific salmon issues.[72] Tawney Lem, Executive Director, West Coast Aquatic Management Association, explained that:

The guardian program, in using that indigenous knowledge, in having people who are in those communities and close to the resource being part of that solution and having them work with sectors and others in the community, absolutely could be a path forward for that aspect of collaboration.[73]

Witnesses such as Eric Angel, Fisheries Program Manager, Nuu‑chah‑nulth Tribal Council, lamented the lack of funding provided to guardian programs, stating:

Our First Nations are always out on the water before anyone else is and yet we struggle to find enough money to ever employ people doing that. Money can go towards having people out on the water, looking, and paying attention to what's going on.[74]

Recommendation 21

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada implement the principles of free, prior, and informed consent, consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, as a foundational component of the consultation and accommodation process with regards to wild salmon.

Recommendation 22

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada collaborate more effectively with First Nations by utilizing guardian programs, Indigenous leadership and traditional ecological knowledge experts and braid these approaches with traditional western science and leadership.

Recommendation 23

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognize decision-making authorities of First Nations and work with them on a nation-to-nation basis along with other governments to plan, implement, monitor, and evaluate salmon management from egg stage to spawning phase.

Recommendation 24

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada recognize that First Nations are in a unique position to lead efforts to rebuild salmon stocks, especially in very remote river systems and watersheds.

Tripartite Coordination and Action

Coordination on Habitat Protection and Restoration

The committee heard evidence about the need for stronger coordination between orders of government, and within the federal bureaucracy, to end siloed actions. Part of the problem, according to Tawney Lem, is that while processes are brought forward, there are no existing relationships from which to have effective Pacific salmon management tables:

[T]he absence of those relationships already being there, it could be difficult for that table to really take hold. In part, one of the things that we've really tried to emphasize is starting to create a bit of a culture, if you will, of collaborating, wherein the communication is made from the top all the way down, and of giving people some concrete ideas of how to bring these tables forward.[75]

On 19 April 2021, the Hon. Chrystia Freeland, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Finance, presented the 2021 federal budget, which included $647.1 million earmarked for preserving wild Pacific salmon.[76] Among the commitments in the budget, was the establishment of a Pacific Salmon Secretariat and Restoration Centre of Expertise (the Secretariat). While the mandate of the Secretariat has not yet been developed, the announcement was welcomed by the Government of British Columbia. Fin Donnelly said that:

the Salmon Secretariat can play a role in bringing to coordinating governments together to address the issues that are continuing to affect salmon and salmon habitat, and looking forward about how we revitalize and work together to recover salmon populations in those critical watershed in those systems that are under the largest threat.[77]

Echoing the call for greater coordination, Robert Chamberlin drew attention to the need for a tripartite, government-to-government-to-government, and properly funded approach, stating:

We need a very broad and cohesive plan informed by First Nations, but that's not going to happen unless there's a key decision and resourcing made from the government to facilitate such a bringing together of all the technical pieces and formulating it into a province-wide strategy, which then can be brought together with the federal and provincial governments.[78]

Recommendation 25

That the newly proposed Pacific Salmon Secretariat and Restoration Centre of Expertise and Fisheries and Oceans Canada develop a thorough overview of completed and proposed initiatives focused on protecting, preserving and restoring wild salmon stocks, and present the Minister with a strategy to coordinate those initiatives, identify duplications and gaps, and recommend program changes and additions necessary to maximize the benefits of investments by governments and communities intended on improving the health and sustainability of those stocks.

Recommendation 26

That the Government of Canada develop the role of the Pacific Salmon Secretariat and Restoration Centre of Expertise in a government-to-government-to-government approach, ensuring that its commitment to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples is honoured.

Program Coordination

The committee heard about the need for integrated and made-in-British Columbia solutions for protecting wild Pacific salmon, through a coordinated approach with First Nations, federal and provincial governments, as well as municipalities and other stakeholders. Jason Hwang recommended that DFO pursue an integrated ecosystem-based salmon recovery strategy, in partnership with First Nations and the Province of British Columbia:

There is a great need and opportunity for increased coordination and collaboration. The federal government and B.C. lack a coordinating framework for salmon-related issues. And underpinning the role of these crown entities are the rights of Canada's indigenous peoples. There is an opportunity to establish a governance and collaboration model where these entities come together to share responsibility and coordinate for salmon.[79]

Fin Donnelly concurred stating that:

British Columbians want us to work with Indigenous leadership, as well as our federal, local and community partners, to ensure these iconic species not only survive but thrive into the future. We're going to continue to build a made-in-B.C. wild salmon recovery strategy that we can all be proud of.[80]

With respect to the role of municipalities, the Parliamentary Secretary for Fisheries and Aquaculture of the Government of British Columbia explained that municipalities are already doing their part with respect to fish passage and habitat restoration, but “[w]hat's needed is a coordinated effort beyond their municipality so that we can stitch them together within watersheds and within ecosystems throughout the province.”[81]

Zo Ann Morten explained how municipalities are not working effectively, underscoring the need for coordination among all parties, and provided the following examples:

We have riparian area regulations, but the ombudsperson said they were not working, and that was the end of it. We just got the report that it was not working, but nobody looked to try to make them actually work. We have a Fisheries Act now in place, but we have regulations that are either ignored or not strong enough to do anything.

This week, Beaver Creek in Stanley Park has been drained. We had spawners in there two weeks ago, and now it's without water. If you go to metro Vancouver, you can have, day to day, moment by moment, how many sewage spills are released into the Fraser River and into Keith Creek, which goes into Lynn Creek.

We have fish passage issues. We have all these issues that have paperwork to go along with them to say this isn't going to happen, but it keeps happening.[82]

Recommendation 27

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada ensure that solutions for restoring wild salmon stocks are localized and community based whenever possible.

Recommendation 28

That the Government of Canada consult with First Nation, provincial and municipal governments, local communities, industries, fish harvesters and workers that are likely to be affected by decisions made by the government for Pacific salmon restoration.

Recommendation 29

That Fisheries and Oceans Canada take advantage of regional decision-making processes that already bring together the range of governments, stakeholders and interested parties effectively and use these processes to ensure that funding intended to rebuild wild Pacific salmon is spent wisely.

Recommendation 30

That the Government of Canada set the table for collaborative management with commercial, recreational, and Indigenous fishers to build a common vision for the future of the fisheries.

Recommendation 31

That the Government of Canada develop an overarching plan to save wild salmon, not just pick and choose ideas that sound appealing without first assessing and understanding the priorities of different needs and options; that this plan includes targets, milestones, and accountability; and that this plan is coordinated between federal, provincial, and First Nation governments.

Implementation of the Wild Salmon Policy

The effective implementation of the WSP rests on reliable data from stock assessments. According to recommendations included in a DFO 2017 consultation report on the implementation of the WSP, there is a need for comprehensive data gathering about the status of wild salmon populations, and a clear process for determining how to prioritize CUs for rebuilding plans, including triggers for developing a plan.[83] However, witnesses pointed out that DFO’s stock monitoring programs “have been cut to the bone.”[84]

Jason Hwang observed that “In terms of monitoring, assessment and data, to summarize, we can't manage what we don't measure.”[85] Alexandra Morton, Pacific Coast Wild Salmon Society, therefore, called for the establishment of a standardized and unified stock monitoring and habitat status assessment system as recommended by the Cohen Commission.[86]

Brad Mirau, President and Chief Executive Officer of Aero Trading Co. Ltd., a seafood processor, added:

It's a lack of information, a lack of proper stock assessment and a lack of data, culminating.... You may know that B.C. no longer has marine stewardship certification on our salmon. Yes, we suspended it as an industry, but it's because DFO has not followed up on its end of the bargain to provide stock assessment and data required for us to hold it.

I will give you an example about the Alaskan fish being caught. Southeast Alaska will catch the chum that we won't catch. We're not allowed to catch them because the stock assessment is not there. Our DFO will not let us catch American chum in the Prince Rupert area because they have insufficient stock assessment.[87]

In Aaron Hill’s opinion, the WSP is an effective policy but DFO has failed to properly implement it to date. He explained:

We also need to implement the wild salmon policy. It's an excellent piece of work, and Justice Cohen agreed. The policy's action steps involve assessing the status of our salmon populations and their habitats and implementing rebuilding plans for the endangered ones, but 15 years later it hasn't happened. The current official implementation plan won't actually get us there. We should study and mitigate the risks of salmon hatcheries. We should do it through the use of a biological risk assessment framework, as promised in the 2005 wild salmon policy.[88]

The committee also heard Myriam Bergeron, Director General, Fédération québécoise pour le saumon atlantique, proposing the use of Quebec’s river-by-river management model of Atlantic salmon.[89] In her view, that approach tailors salmon management to each river and has ensured both the conservation of the resource and the sustainable development of the sport fishery in Quebec.

Recommendation 32

That the newly proposed Pacific Salmon Secretariat and Restoration Centre of Expertise be mandated to ensure the implementation of Canada's Policy for Conservation of Wild Pacific Salmon.

Conclusion

Since the release of the WSP over 15 years ago, DFO has had little success in stabilizing, let alone restoring at-risk wild Pacific salmon populations. In the committee’s opinion, the status quo in salmon management cannot restore these depleted populations in the challenging context of climate change affecting both ocean conditions and the freshwater environment.

The committee is encouraged by the 2021 federal budget’s significant investment earmarked for preserving wild salmon and calls on DFO to implement recommendations put forward in this report. These recommendations would ensure the long-term health of wild Pacific salmon as well as fisheries and coastal communities that depend on them. In the committee’s view, recommendations brought forward in this report should inform DFO’s development of the Pacific Salmon Strategy called for by the Minister’s 2021 supplementary mandate letter.[90]

[1] British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, First Nations Summit and Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, Wild Salmon Summit: Summary Report, 19–21 September 2018.

[2] Fisheries and Oceans Canada [DFO], Chinook Salmon Abundance Levels and Survival of Resident Killer Whales, Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Science Advisory Report 2009/075, April 2010.

[3] G.S. Gislason & Associates Ltd. and Institute of Social & Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage, Economic Impacts of Pacific Salmon Fisheries, prepared for the Pacific Salmon Commission, July 2017.

[5] Pacific Salmon Foundation, Salmon Facts.

[8] B. Riddell, K. Connors, and E. Hertz, The State of Pacific Salmon in British Columbia: An Overview, The Pacific Salmon Foundation, Vancouver, B.C., Canada, 2018.

[9] J. Walsh et al., “A Window Opens for Pacific Canada’s Wild Salmon Policy,” Policy Options, 30 October 2017.

[10] Privy Council Office, Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River—Final Report, 31 October 2012.

[11] Government of Canada, Species Search, Species at risk registry.

[12] S.C.H. Grant, B. MacDonald and M.L. Winston, State of Canadian Pacific Salmon: Responses to Changing Climate and Habitats, Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 3332, DFO, 2019.

[15] Dustin Snyder, Director, Stock Rebuilding Programs, Spruce City Wildlife Association, Evidence, 11 August 2020.

[16] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 23 July 2020.

[17] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, As an Individual, Evidence, 14 April 2021.

[18] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, As an Individual, Evidence, 14 April 2021.

[20] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, As an Individual, Evidence, 14 April 2021.

[21] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[22] Marvin Rosenau, Instructor, Fish, Wildlife and Recreation Program, British Columbia Institute of Technology, As an Individual, Evidence, 24 March 2021.

[23] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, As an Individual, Evidence, 14 April 2021.

[24] Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[25] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[27] Marvin Rosenau, Instructor, Fish Wildlife and Recreation Program, British Columbia Institute of Technology, As an Individual, Evidence, 24 March 2021.

[29] Kathy Scarfo, President, West Coast Trollers Association, As an Individual, Evidence, 13 August 2020.

[30] John Paul Fraser, Executive Director, BC Salmon Farmers Association, Evidence, 7 December 2020.

[34] Jay Parsons, Director, Aquaculture, Biotechnology and Aquatic Animal Health Science Branch, DFO, Evidence, 26 April 2021.

[35] Brian E. Riddell, Science Advisor, Pacific Salmon Foundation, As an Individual, Evidence, 14 April 2021.

[37] Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[38] DFO, Government of Canada Takes Action to Address Fraser River Chinook Decline, 16 April 2019.

[39] DFO, Guidance for the Development of Rebuilding Plans Under the Precautionary Approach Framework: Growing Stocks Out of the Critical Zone.

[41] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 23 July 2020.

[42] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 23 July 2020.

[43] E. Plate, R. C. Bocking and K. K. English, Responsible Fishing in Canada’s Pacific Region Salmon Fisheries, Prepared for the Pacific Fisheries Resource Conservation Council, February 2009.

[44] Kathy Scarfo, President, West Coast Trollers Association, As an Individual, Evidence, 13 August 2020.

[45] Owen Bird, Executive Director, Sport Fishing Institute of British Columbia, Evidence, 7 December 2020.

[46] Jesse Zeman, Director of Fish and Wildlife Restoration, B.C. Wildlife Federation, Evidence, 23 July 2020.

[47] Carl Walters, Professor Emeritus, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia, As an Individual, Evidence, 23 July 2020.

[57] S1 smolts have spent one winter in a hatchery’s freshwater environment before going to sea, and S0 smolts go to sea before their first winter.

[60] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, “Recommendation 16” in Protection and Recovery of Endangered Whales: the Way Forward, Report 18, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, December 2018.

[62] Owen Bird, Executive Director, Sport Fishing Institute of British Columbia, Evidence, 7 December 2020.

[63] Owen Bird, Executive Director, Sport Fishing Institute of British Columbia, Evidence, 7 December 2020.

[65] Hon. Bernadette Jordan, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard, Evidence, 2 June 2021.

[66] Greg Witzky, Operations Manager, Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat, Evidence, 21 July 2020.

[67] Greg Witzky, Operations Manager, Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat, Evidence, 21 July 2020.

[71] Greg Witzky, Operations Manager, Fraser River Aboriginal Fisheries Secretariat, Evidence, 21 July 2020.

[73] Tawney Lem, Executive Director, West Coast Aquatic Management Association, Evidence, 1 February 2021.

[75] Tawney Lem, Executive Director, West Coast Aquatic Management Association, Evidence, 1 February 2021.

[76] Government of Canada, “Preserving Wild Pacific Salmon,” Chapter 5: A Healthy Environment for a Healthy Economy—Part 2: Creating Jobs and Growth in Budget 2021, 19 April 2021.

[77] Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[80] Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[81] Fin Donnelly, Parliamentary Secretary, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Government of British Columbia, Evidence, 5 May 2021.

[82] Zo Ann Morten, Executive Director, Pacific Streamkeepers Federation, Evidence, 9 December 2020.

[83] DFO, What We Heard: Report on Consultation and Response from the Fall 2017 Draft Initial Wild Salmon Policy Implementation Plan Meetings, 2018–2022 Implementation Plan.

[86] Alexandra Morton, Pacific Coast Wild Salmon Society, As an Individual, Evidence, 11 August 2020.

[87] Brad Mirau, President and Chief Executive Officer, Aero Trading Co. Ltd., Evidence, 13 August 2020.

[89] Myriam Bergeron, Director General, Fédération québécoise pour le saumon atlantique, Evidence, 12 May 2021.

[90] Prime Minister of Canada, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Supplementary Mandate Letter, 15 January 2021.