RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INSECT MANAGEMENT IN CANADA’S FOREST SECTOR

Introduction

In June 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources (the committee) agreed to study and develop recommendations needed to protect the Canadian forestry sector from the spread of forest insects, including the mountain pine beetle and the spruce budworm. Over the course of six meetings, the committee heard from a wide range of experts about the impacts of insect infestations on Canada’s people, economy and environment, as well as best practices for managing outbreaks moving forward. The committee is pleased to present its final report, including the study findings and recommendations to the Government of Canada.

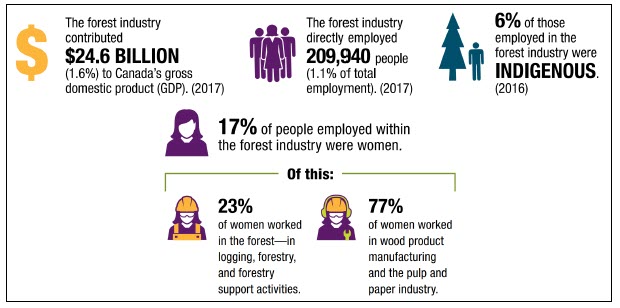

Figure 1: Canada’s Forest Sector at a Glance

Source: Natural Resources Canada.

Accounting for roughly 35% of the Canadian landmass, forests are an integral part of Canada’s environment, economy and way of life. The committee heard that the forest industry is active in about 600 communities across the country, including more than 150 in rural areas, and that “80% of [Canada’s] First Nations communities call the forest home.”[1] In 2017, the $69-billion industry contributed $24.6 billion to national gross domestic product (GDP) and employed 209,940 people directly (Figure 1). Forests are also natural carbon sinks and could help Canada meet its greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets under the Paris Agreement. In 2015, forests removed an estimated 26 million tonnes of carbon dioxide from Canada’s GHG inventory.[2]

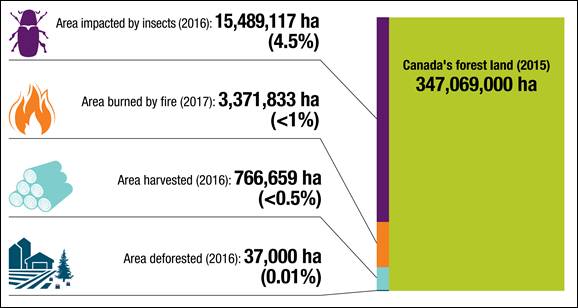

Figure 2: Forest Disturbance in Canada

Source: Natural Resources Canada.

Forest insects are the biggest cause of tree mortality in Canada (Figure 2). Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that their disturbance of forests may be getting worse.[3] The aim of this report is to provide policy guidance to the Government of Canada on how to enhance national insect management, based on evidence from diverse experts from industry, civil society, academia, Indigenous organizations and the public sector. The next two sections outline Canada’s major forest insect outbreaks and their impacts. The final section discusses best practices for multi-stakeholder insect management across jurisdictions.

The committee is aware that many organizations refer to undesirable forest insects as pests. However, Bradley Young of the Native Aboriginal Forestry Association indicated that the term carries negative ideological connotations. He explained that Indigenous elders do not use such terms, “instead referring to the little ones as man îcosak, or some other respectful Indigenous nomenclature in Cree, Dene, Blackfoot, Haida, etc.”

Major Outbreaks

Canada’s forest insects can be classified into three broad categories: native, alien and invasive. Native species have lived in Canadian forests for thousands of years, contributing to essential lifecycle functions such as forest renewal and regrowth. Only in the event of an infestation or outbreak do they become harmful to forest ecosystems and resources. Alien and invasive species, on the other hand, are foreign to the ecosystems to which they are introduced. They often arrive with no natural enemies, attacking trees that have not adapted defense mechanisms against them. According to Tracey Cooke of the Invasive Species Centre, “a species is invasive if it is introduced outside of its native range and has potential negative impacts on ecology, economy or society in its introduced range.” Alien insects are species introduced into Canada’s forests within recent history.[4]

[Indigenous cultures] place the insect family within the circle of life and readily acknowledge that in many ways they are both much more powerful and much more fearsome than humans can ever hope to be.

Bradley Young, Native Aboriginal Forestry Association

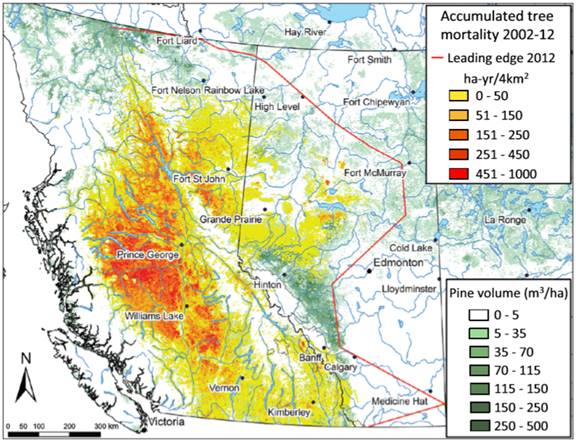

The committee heard that Canada’s two most persistent outbreaks of native species are the mountain pine beetle of Western Canada and the spruce budworm of the boreal, Great Lakes and Acadian forest regions. The current beetle outbreak started in British Columbia in the late 1990s and has since spread northward and eastward beyond its native range of lodgepole pines. Breaching the Rocky Mountains, it is now considered an invasive species for reproducing in the jack pine of the boreal forest. The insect has caused tree mortality over roughly 16 million hectares of pine-dominated forests in British Columbia. Witnesses think it has the potential to continue its invasive spread through Alberta and beyond (Figure 3).[5]

Figure 3: Accumulated Tree Mortality by the Mountain Pine Beetle, 2002-2012

Source: RNNR Evidence, Alex Chubaty (Healthy Landscapes Program), based on Cooke BJ, Carroll AL. (2017).

In Eastern Canada, evidence dating back to the 1700s indicates that cyclical outbreaks of the spruce budworm have been occurring every 30 to 40 years. Since 2006, budworm populations have been growing steadily in Quebec, affecting approximately 7 million hectares of trees in 2017. The outbreak spread from the lower St. Lawrence to northern New Brunswick in 2016, reaching the Miramichi region in 2017. According to Chris Ward of the Government of New Brunswick, the budworm is the greatest insect threat to forests in his province.[6]

Witnesses discussed major outbreaks of other forest insects, including the Jack pine budworm of Ontario, Manitoba and Saskatchewan; the Douglas-fir, spruce and balsam bark beetles of British Columbia; as well as alien species such as the Eurasian gypsy moth, the Asian long-horned beetle and emerald ash borer, and the European brown spruce longhorn beetle.[7]

Impacts and Threat Factors

The committee heard that ongoing insect outbreaks affect Canada’s environment, economy and forest-dependent communities by having the following impacts:

- Damaging forest health and biodiversity, in turn creating new pathways for more insect outbreaks. According to Ms. Cooke, invasive insects are considered “the second greatest threat to global biodiversity, next to habitat loss.” By attacking and killing large numbers of trees, they can “reduce habitat for native animals and insects, create canopy gaps altering the microclimate of the forest, and make that forest even more vulnerable to additional invasive species, overall reducing biodiversity.”

- Diminishing the supply and quality of wood fibre, thereby affecting forestry employment and economic activity.[8] The mountain pine beetle has destroyed over 50% of the loggable pine in British Columbia, putting forest-dependent communities and businesses at risk.[9] In New Brunswick, records show that outbreaks of spruce budworm could lead to up to 20% reduction in wood supply.[10] Alien insects, such as the European and Asian gypsy moths, are also known to threaten the forest economy by targeting economic tree species.[11]

- Threatening Canada’s natural heritage, including national parks and urban trees.[12] According to Darlene Upton of Parks Canada, current insect outbreaks are threatening several historic sites and parks across Canada, including Banff, Kootenay, Yoho, Jasper, Kouchibouguac and possibly Fundy National Park. As Beth McEwen of the City of Toronto pointed out, the economic, social and emotional value of trees should not be underestimated: “the rally to save the oak tree on Coral Gable Drive in [Toronto’s] North York is testament to the emotional connection that some residents develop with trees.” Ms. McEwen added that outbreaks of forest insects and diseases have led to “significant economic impacts on Canadian forests.”

- Possibly increasing the risk of wildfire. Emerging data suggests that, by killing trees, forest insects may increase the fuel load for wildfires.[13] According to Ms. Upton and Kim Connors of the Canadian Interagency Forest Fires Centre, this hypothesis can be partially supported by observations that wildfires tend to occur more frequently and/or severely in areas affected by forest insects, as evidenced in British Columbia (2017-2018) and Ontario (2018).

- Contributing to Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions. When trees age, get damaged or die, they turn from carbon sinks to carbon sources. In that sense, insect outbreaks are reducing the natural sequestration capacity of Canada’s forests.[14]

Forest insects can spread through various trade and transportation routes. As William Anderson of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) stated, they are “notorious hitchhikers […] not restricted to agricultural and forest commodities. They have been found on everything from car parts to furniture and decorations.” The movement of firewood and ash logs is among the risk factors to watch for in day-to-day activities, as indicated by the CFIA’s Don’t Move Firewood campaign.

Given its origin and magnitude, the mountain pine beetle epidemic is one of the most frequently cited examples of climate change impacts in the world.

Étienne Bélanger, Forest Products Association of Canada

The committee also heard that wildfire suppression and climate change are facilitating the spread of forest insects through environmental pathways.[15] For example, according to Professor Allan Carroll of the University of British Columbia, successful wildfire suppression nationwide, and particularly in his province, has caused an increase in the number of older trees, “the preferable food source for the mountain pine beetle,” allowing beetle populations to build to “unprecedented levels.” Furthermore, over the past few years, the mountain pine beetle outbreak has been exacerbated by fewer stretches of the cold temperatures needed to control the insect’s populations during the winter (i.e., -35°C to -40°C), and drier summers, leading to more water-stressed and beetle-susceptible trees.[16]

Witnesses further explained that changes in weather patterns can diminish the health of forests, thereby weakening their resistance to alien and invasive species. According to Chris Norfolk of the Government of New Brunswick, it is this “cumulative impact, not only of the direct environmental condition created by climate change through either extreme weather events or warmer weather, but also of the emergence of new pest pathways, that certainly will create challenges for integrated pest management in the future.”

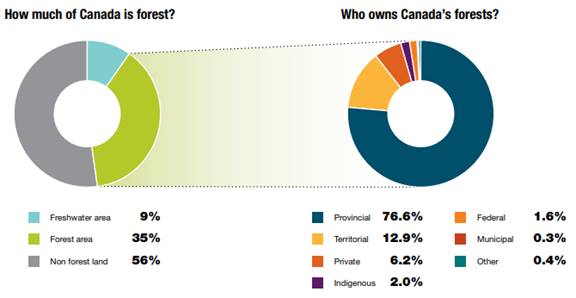

Cross-Border Cooperation

Close to 90% of Canadian forests fall under the jurisdiction of the provinces and territories. Of the remainder, 6.2% are private property, 2% are owned by Indigenous peoples, and 1.6% belong to the Government of Canada (Figure 4). At the federal level, the Canadian Forest Service (CFS) provides research and policy support by monitoring forest insects and developing solutions to outbreaks in several research centres across the country; Parks Canada is responsible for insect management strategies within national parks; and the CFIA works to protect Canadian resources and the environment from invasive foreign insects by monitoring and inspecting regulated pathways of plant products. The CFIA is also Canada’s representative to the International Plant Protection Convention, promoting the development and implementation of international plant health standards and practices.[17]

Figure 4: Forest Land Ownership in Canada

Source: Natural Resources Canada.

Forest pests do not recognize municipal, provincial or international boundaries. Federal government scientists are well positioned to coordinate research for pests that are considered a high risk to Canadian forests.

Beth McEwen, City of Toronto

Witnesses stressed the need for cross-jurisdictional partnerships to develop effective insect management strategies, highlighting the importance of the research and financial support provided by the federal government.[18] For instance, Mr. Ward told the committee that the Healthy Forest Partnership’s Early Intervention Strategy (EIS) to tackle the spruce budworm in Atlantic Canada has yielded measurable results:

The collaborative nature of the EIS program is a model for how management of large-scale disturbance can be successfully implemented. It demonstrates that multiple agencies with differing interests and goals can work effectively toward a common objective of preserving forest values from the destructive nature of the spruce budworm. The results of the [EIS] have been a measurable success. Less than 1,000 hectares of defoliation were identified in New Brunswick in 2018, which is less than that identified in 2017.

Furthermore, the committee heard that federal-municipal collaboration with the City of Toronto has brought the Asian long-horned beetle “very close to eradication,”[19] and that intergovernmental efforts with Alberta and Saskatchewan to combat the eastern spread of the mountain pine beetle have made some progress.[20] Witnesses highlighted other partnerships involving the federal government, including the National Forest Pest Strategy, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada’s Turning Risk Into Action for the Mountain Pine Beetle Epidemic Network (NSERC TRIA-Net), the Canadian Urban Forest Strategy, and the North American Plant Protection Organization, among others.

Despite these efforts, the committee heard that more work is needed to improve Canada’s response and adaptive capacity to current and future outbreaks of forest insects. To this end, witnesses recommended that governments and forest managers consider the following measures:

- Building on preventative and early intervention strategies by enhancing active surveillance, risk pathway analysis, border inspections and reporting.[21] As Mr. Anderson put it, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Once an invasive species takes hold at the landscape level, eradication becomes less likely and more expensive.[22] Witnesses discussed several models of early outbreak detection and response, including Atlantic Canada’s EIS; the Early Detection & Rapid Response (EDRR) Network Ontario project; and the multijurisdictional Early Detection & Distribution Mapping System. According to Mr. Ward, the EIS is “a $300-million approach to a $15-billion problem.” It has the potential to become the new standard for managing insect outbreaks across the country.[23]

- Ensuring sustainable public funding to support long-term action against persistent insect outbreaks, such as that of the mountain pine beetle. The committee heard that many forest managers could use additional funding to improve insect management within their jurisdiction.[24] With regards to the mountain pine beetle outbreak, witnesses stressed the need for consistent multigovernmental support to reduce the beetle’s likelihood of further spread eastward.[25] According to Diane Nicholls of the Government of British Columbia, the most beneficial collaboration on the part of the federal government has been to provide funds with clearly-defined results (i.e., indicate “what the funds could be used for and how they should be used”), while letting the province implement them.

- Eliminating knowledge gaps across jurisdictions through training/skill transfer opportunities and public awareness. As witnesses pointed out, forest insects do not recognize political borders. Effective insect management depends on the capacity of neighbouring jurisdictions to act with comparable knowledge and skill. Ms. Cooke recommended that the federal government coordinate a data-sharing network to allow everyone access to the same information. Furthermore, several witnesses highlighted the importance of skills training and public awareness campaigns to engrain risk-reduction practices into societal norms. The CFIA’s “Don’t Move Firewood” is one example of such campaign.[26]

- Incorporating Indigenous knowledge in forest insect management practices, in line with the Crown’s duty to consult.[27] While there is evidence of growing collaboration between Indigenous peoples and Canadian governments, the committee heard that more work needs to be done in this area. Mr. Atkinson called for “investment in First Nations research that can bring forward traditional knowledge and understanding of lands and resources.” Furthermore, Mr. Young pointed out that strengthening Indigenous engagement requires resourcing and “creating the table space where [Indigenous] solutions can come.”

- Supporting municipalities in their efforts to address outbreaks within their jurisdiction.[28] Considering that invasive species spread through common shipping and trade routes, many insect outbreaks start in urban settings.[29] In Canada, municipalities are the constitutional responsibility of the provinces. Nevertheless, Michael Rosen of Tree Canada suggested that urban forestry should be reflected in federal policy, as is the case in other G7 countries. The Federation of Canadian Municipalities called on the federal government to “involve municipalities in the development and delivery of forest pest programs, and provide resources to local governments in instances where municipalities are directly involved in limiting the spread of forest pests.”

- Adapting forest management practices and policies to ecological and climate change.[30] The committee heard that forest management practices need to adapt to changes in the forest environment. For example, witnesses indicated that research can be expanded to better understand the behaviour of invasive species, such as the mountain pine beetle, in new host environments;[31] that harvesting regimes can be amended to account for insect-infected wood;[32] and that government policy can be adapted to allow for greater diversification of tree species and forest structures.[33] Many witnesses brought up the point that some reforestation techniques have weakened the forest’s ability to survive stresses such as pest outbreaks.[34] It was particularly noted that foresting a plot, and then replanting a single species (such as the lodge pole pine) in such a way that the homogeneity does not reflect the natural forest’s layout, weakens the forest’s resilience. As Gilles Seutin of Parks Canada explained, forests of more diverse composition are less susceptible to large-scale infestation and impact. According to Étienne Bélanger, “many of the legal foundations of existing forest regimes do not allow for the necessary changes [to forest composition].”

Witnesses called on the federal government to scale up Canada’s national dialogue on forest insect management in collaboration with governments and stakeholders across jurisdictions.[35] Derek MacFarlane asserted that the CFS is widely seen as “the only national entity that can bring key players to the table to produce relevant and practical science-based results” of benefit to regional forest managers and policy makers.

[1] Standing Committee on Natural Resources (RNNR), Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament (Evidence): Bradley Young (Executive Director, National Aboriginal Forestry Association [NAFA]).

[2] RNNR Evidence: Derek MacFarlane (Regional Director General, Canadian Forest Service, Atlantic Forestry Centre, Department of Natural Resources [NRCan]); Étienne Bélanger (Director, Forestry, Forest Products Association of Canada [FPAC]); Richard Briand (Chief Forester, West Fraser Mills Ltd.); and Young (NAFA).

[3] RNNR Evidence: Allan Carroll (Professor, Department of Forest and Conservation Sciences, University of British Columbia [UBC]).

[4] RNNR Evidence: Tracey Cooke (Executive Director, Invasive Species Centre); David Nisbet (Partnership and Science Manager, Invasive Species Centre); MacFarlane (NRCan); Jean-Luc St-Germain (Policy Analyst, Science Policy Integration Branch, Research Coordination and Integration Division, Canadian Forest Service, NRCan); Carroll (UBC); Young (NAFA); and Natural Resources Canada.

[5] RNNR Evidence: Carroll (UBC); Bélanger (FPAC); Briand (West Fraser Mills); Darlene Upton (Vice-President, Protected Areas Establishment and Conservation, Parks Canada Agency); Peter Henry (Manager, Forest Guides and Silviculture, Policy Division, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Government of Ontario); Young (NAFA); MacFarlane (NRCan); and Diane Nicholls (Assistant Deputy Minister, Chief Forester, Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development of British Columbia, Government of British Columbia).

[6] RNNR Evidence: Upton (Parks Canada); Chris Ward (Acting Assistant Deputy Minister, New Brunswick Department of Energy and Resource Development, Government of New Brunswick); Henry (Government of Ontario); Young (NAFA); and MacFarlane (CFS).

[7] RNNR Evidence: Henry (Government of Ontario); Young (NAFA); Nicholls (Government of British Columbia); and Beth McEwen (Manager Forest and Natural Area Management, Urban Forestry, City of Toronto).

[8] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane (NRCan); Briand (West Fraser Mills Ltd.); Cooke (Invasive Species Canada); William Anderson (Executive Director, Plant Health and Biosecurity Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency [CFIA]); Nicholls (Government of British Columbia); Ward (Government of New Brunswick); Gail Wallin (Chair, Canadian Council on Invasive Species [CCIS]); and Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

[9] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane (NRCan); Briand (West Fraser Mills Ltd.); Nicholls (Government of British Columbia).

[12] RNNR Evidence: Upton (Parks Canada); McEwen (City of Toronto); Federation of Canadian Municipalities.

[13] RNNR Evidence: Carroll (UBC); Chubaty (Healthy Landscapes Program); Briand (West Fraser Mills); Upton (Parks Canada); Nisbet (ISC).

[14] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane (NRCan).

[15] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane (NRCan); Bélanger (FPAC); Carroll (UBC); Nicholls (Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development of British Columbia); McEwen and Ric (City of Toronto); Chubaty (Healthy Landscapes Program); Norfolk (New Brunswick Department of Energy and Resource Development); Henry (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry); Seutin (Parks Canada); Rosen (Tree Canada); fRI Research.

[16] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane (NRCan); Bélanger (FPAC); Carroll (UBC); Nicholls (Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development of British Columbia); fRI Research.

[17] RNNR Evidence: MacFarlane and St-Germain (NRCan); Upton (Parks Canada); Anderson (CFIA); Bélanger (Forest Products Association of Canada); Forest land ownership and Canada’s forest laws (NRCan).

[18] RNNR Evidence: McEwen of the City of Toronto; Henry (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry); Ward and Norfolk (New Brunswick Department of Energy and Resource Development); Upton (Parks Canada); MacFarlane and St‑Germain (NRCan); Cooke (ISC); Carroll (As an individual); Anderson (CFIA); Briand (West Fraser Mills); Keith Atkinson (Chief Executive Officer, BC First Nations Forestry Council); and Michael Rosen (President, Tree Canada).

[20] RNNR Evidence: Briand (West Fraser Mills); and Alex Chubaty (Spatial Modelling Coordinator, fRI Research, Healthy Landscapes Program, As an Individual).

[21] RNNR Evidence: Anderson (CFIA); Cooke (Invasive Species Centre); Wallin (CCIS); Ward (Government of New Brunswick); MacFarlane (NRCan); Rosen (Tree Canada); McEwen (City of Toronto); and Canadian Council on Invasive Species.

[23] RNNR Evidence: Ward (Government of New Brunswick); MacFarlane (NRCan).

[24] RNNR Evidence: Cooke (Invasive Species Centre); Young (NAFA); McEwen (City of Toronto); Briand (West Fraser Mills); Bélanger (FPAC); Atkinson (BC First Nations Forestry Council); Chubaty (As an Individual); and Canadian Council on Invasive Species.

[25] RNNR Evidence: Carroll (UBC); Briand (West Fraser Mills); Chubaty (As an Individual); and David MacLean (Emeritus Professor, University of New Brunswick, As an Individual).

[26] RNNR Evidence: Cooke and Nisbet (Invasive Species Centre); Rosen (Tree Canada); Léo Duguay (Vice-Chair, Board of Directors, Tree Canada); Ward (Government of New Brunswick); McEwen (City of Toronto); and Nicholls (Government of British Columbia).

[28] RNNR Evidence: Federation of Canadian Municipalities; and Rosen (Tree Canada).

[30] RNNR Evidence: Carroll (UBC); Nicholls (Government of British Columbia); fRI Research; Henry (Government of Ontario); Wallin (CCIS); McEwen (City of Toronto); Atkinson (BC First Nations Forestry Council); Kim Connors (Executive Director, Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre); and Young (NAFA).

[32] RNNR Evidence: Upton (Parks Canada); MacLean (As an Individual); MacFarlane (NRCan); Chubaty (As an Individual); and Nicholls (Government of British Columbia).

[33] RNNR Evidence: Carroll (UBC); MacLean (As an Individual); Chubaty (As an Individual); and Bélanger (FPAC).

[34] Ibid.

[35] RNNR Evidence: Bélanger (FPAC); Cooke (Invasive Species Centre); Young (NAFA); McEwen (City of Toronto); Chubaty (As an Individual); Federation of Canadian Municipalities; and Canadian Council on Invasive Species.