OGGO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Improving Transparency and Parliamentary Oversight of the Government’s Spending Plans

Introduction

“The big thing around here—I'm saying broadly Parliament—is that there are people who have been here a long time as members of Parliament who don't really understand the estimate and budget processes. It's not really their fault.”

Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board, 24 October 2016

Parliamentarians play a critical role in reviewing and approving the government’s spending plans through the business of supply, which is often referred to as the estimates process. As part of this process, it is presumed that parliamentary committees will closely scrutinize the government’s spending plans and the associated departmental plans and results, based on the votes and reports that are referred to them. To fulfil this role, parliamentarians need information that is understandable, complete, timely, and prepared on a consistent basis.

The business of supply and the principles underlying Canada’s parliamentary financial cycle date back to Confederation and beyond, as they are based on the British House of Commons’ financial procedures.[1] While supply procedures remained largely unchanged for the first hundred years following Confederation, since that time there have been many changes. Some of the changes to supply procedures were the result of several wide-ranging parliamentary reviews of the process undertaken in recent years.[2]

Notably, the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (the Committee) has the mandate to review the process for considering estimates and supply, and the format and content of all estimates documents. Since its creation, the Committee has examined ways to improve the estimates process. In 2003, the Committee released a report entitled Meaningful Scrutiny: Practical Improvements to the Estimates Process, followed by another report in 2012, called Strengthening Parliamentary Scrutiny of Estimates and Supply, which contained 16 recommendations. In response to the 2012 report, the federal government began highlighting new funding and federal budget items in estimates documents. It also revised the content requirements of the reports on plans and priorities (renamed the departmental plans), undertook a pilot project on purpose-based votes with Transport Canada, and created an online searchable database of government spending information.

Despite these changes, the estimates process remains complex and lacks meaningful parliamentary scrutiny. When the Committee started this study, there were several reasons for this:

- the lack of alignment between the federal budget and the estimates;

- the lack of consistency in the accounting basis used in the federal budget, the estimates documents and the government’s financial statements;[3] and

- the disconnect between appropriations and program objectives due to the structure of estimates votes, which are currently not purpose-based.

In 2015, the President of the Treasury Board’s mandate letter set improving the transparency and integrity of government spending as a top priority. This was to be achieved by:

- 1) strengthening the oversight of taxpayer dollars and the clarity and consistency of financial reporting;

- 2) ensuring consistency and maximum alignment between the estimates and the public accounts; and

- 3) exercising due diligence regarding costing analysis.[4]

In October 2016, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) released a report entitled Empowering parliamentarians through better information which outlined a four-pillar approach “to improve the reporting process to increase accountability to Parliament and Canadians.” The four pillars touch upon:

- 1) the timing of the estimates;

- 2) the differences in scope and accounting methods between the federal budget and the estimates;

- 3) the structure of voted funds; and

- 4) departmental plans and departmental results reports.

The Committee has continued to follow the evolution of the estimates process and the challenges it presents with interest. In 2016, it launched a study to explore ways to improve the process. Between February 2016 and June 2018, the Committee held 11 meetings and heard from 31 witnesses, including the President of the Treasury Board; officials from the TBS, the Privy Council Office, Finance Canada and Transport Canada; the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG); the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO); experts from Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada); and government representatives from the United Kingdom, Australia, and Ontario. In addition, the Committee devoted six meetings, between April and June 2018, to examining the 2018–2019 Main Estimates, during which it considered recent changes to the estimates process. The full list of witnesses can be found in Appendices A, B, and C.

CHAPTER 1: ALIGNING THE FEDERAL BUDGET AND THE MAIN ESTIMATES

“[O]ne of the benefits we see [in the U.K.] in aligning the estimates, the budgets, and ultimately the financial accounts is that it has improved transparency. It is easier to track the Treasury's expenditure plans.”

Michael Sunderland, Acting Deputy Director, Government Financial Reporting, Her Majesty's Treasury, 14 June 2016

While the federal government outlines its spending and tax measures in its annual budget, it presents its spending plans in estimates documents for parliamentary approval. In the past, measures announced in the federal budget were not included in the main estimates; instead, they were presented in supplementary estimates. According to the testimony the Committee heard, this lack of alignment between the federal budget and the main estimates was due to the following two challenges:

- the timing of the presentation of the federal budget and the tabling of the main estimates (the main estimates were prepared before the federal budget was presented); and

- the lack of collaboration between the Department of Finance, which is responsible for the preparation of the federal budget, and TBS, which is responsible for the preparation of the estimates documents.

To reach a better alignment between the federal budget and the main estimates, the federal government introduced temporary changes to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons. These changes delayed the tabling of the main estimates so that they would follow the federal budget rather than precede it. The present chapter presents the main components of the parliamentary financial cycle before discussing the challenges identified by witnesses and the temporary changes implemented.

Among its fundamental roles, Parliament must review and approve the federal government’s taxation and spending plans. As described by Scott Brison, President of the Treasury Board, “[t]he ability to exercise oversight over government spending is the most important role that ... parliamentarians can play in representing Canadians.”

1.1 Main components of the Parliamentary Financial Cycle

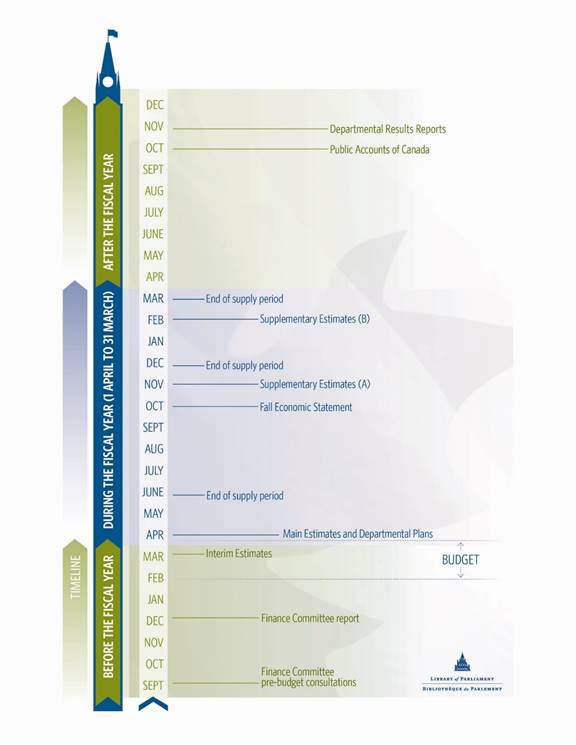

Michael Ferguson, Auditor General of Canada, discussed the three main components of the parliamentary financial cycle. He explained that the federal budget and the estimates are the first two steps in the government’s financial reporting and accountability cycle, while the public accounts of Canada end that cycle. Figure 1 presents the current parliamentary financial cycle and shows which activities occur before, during or after the fiscal year, which begins on 1 April and ends on 31 March.

Figure 1—The Parliamentary Financial Cycle

The federal budget outlines the government’s taxation and spending priorities for the fiscal year to come. Although there is no obligation for the government to prepare a budget and no fixed budget date, the Minister of Finance usually releases a budget in February or March.

The government tables the main estimates in the House of Commons to obtain authorization to spend public funds for the current fiscal year. Under the temporary measures, applied to fiscal years 2018–2019 and 2019–2020, these estimates must be tabled no later than 16 April. Previously, the deadline had been 1 March. The main estimates outline the spending plans of each federal organization along with items that will be part of the appropriation bill for Parliament’s approval. Minister Brison clarified that “the details involved in the main estimates are far greater than those in the budget. A budget gives a general view and a perspective … but the details come out [in the estimates].” Brian Pagan, Assistant Secretary, Expenditure Management, TBS, commented that

[t]he estimates are clearly essential to the proper operation of government. They form the basis of parliamentary oversight and control, reflect the government's spending priorities, and serve as the principal mechanism for establishing reports on plans and results.

In discussing the different scope of the budget and the estimates, Minister Brison acknowledged that “parliamentarians need to be able to compare items in the budget and estimates.”

Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, Department of Finance, explained that the estimates, unlike the federal budget, do not include all government spending, such as expenditures related to employment insurance, tax expenditures (i.e., refundable tax credits), Crown corporations’ expenses and revenues credited to the vote.

1.2 Improving the Alignment of the Processes

As previously explained, some witnesses identified the timing of the federal budget and the tabling of the main estimates as one of the main challenges contributing to the lack of alignment between the documents. Several witnesses cited this misalignment as being a significant challenge to financial transparency. They pointed out that it prevents Parliament from scrutinizing the government’s entire spending plans at the beginning of the fiscal year when it examines the main estimates.

Yaprak Baltacioglu, Secretary of the TBS, explained that programs and initiatives included in the estimates documents require a greater level of detail and preparation than they do in the federal budget. According to Mr. Pagan, departments and agencies develop Treasury Board submissions for new initiatives, which include program terms and conditions, the number of human resources required, the expected results, the success indicators, the partners involved, and the contracts needed, if any. During the Treasury Board submission process, departmental costings and program details are scrutinized to ensure that departments and agencies are ready to implement the programs once Parliament approves the funds. Moreover, Treasury Board must approve these submissions before they appear in the estimates documents that Parliament approves. Items included in Vote 40, however, had not yet gone through Treasury Board submission process and had not yet been approved by Treasury Board, but were nonetheless presented in the main estimates for 2018–2019.

Mr. Pagan informed the Committee that the delay between the budget measure being announced and Treasury Board approval varies depending on the initiative and whether it involves detailed discussions and negotiations with other parties. It is not uncommon to see budget items from the previous year’s budget in subsequent supplementary estimates. For example, the Department of Global Affairs’ International Education Strategy was announced in the 2013 federal budget tabled in March of that year, but the department began to receive funding for that strategy some 19 months later under the 2014–2015 Supplementary Estimates (B), which were approved in December 2014.[5]

Mostafa Askari, Assistant PBO, pointed out that Treasury Board’s due diligence takes place after the federal budget is tabled, unlike in Australia where the budget measures are scrutinized by the Treasury before the tabling of the budget because of prior coordination between the Department of Finance and the Treasury. As a way to improve the alignment of the federal budget with the main estimates, he suggested integrating the Cabinet approval process with the Treasury Board submission process, as is the case in Australia and Ontario. Currently, the Cabinet process takes place before the federal budget is tabled and, once completed, the Treasury Board submission process begins.

In response to a question, Alex Smith, Financial Analyst, Office of the PBO, said that the creation of an expenditure review committee would be a way to align the Department of Finance and Treasury Board processes. He indicated that this could lead to a full integration of the federal budget and the main estimates, which could then be presented at the same time.

1.3 Better Collaboration between Departments

Several witnesses discussed the need for closer collaboration between the Department of Finance and TBS to achieve a better alignment of the federal budget and the estimates. For example, Jean-Denis Fréchette, PBO, indicated that substantial reforms to the budgetary approval processes of the Department of Finance and Treasury Board would be required to reach a proper alignment. He added that, in fiscal year 2016–2017, many of the budget spending measures included in the supplementary estimates had either less or more spending attached to them than was indicated in the federal budget, since departments refined the forecast costs once they developed the programs and initiatives for the Treasury Board submission process. According to Jason Jacques, Director, Economic and Fiscal Analysis, Office of the PBO, the government should prioritize fixing internal processes and increasing the collaboration between the Department of Finance and TBS.

Mr. Leswick acknowledged that greater collaboration between the Department of Finance and TBS would be required to table a federal budget at the same time as the main estimates, as the two documents are prepared by different departments. However, he added that there is already a certain degree of collaboration between the two departments, which are located in the same building. Minister Brison echoed that view and said that improving the alignment of the federal budget and the estimates is an opportunity to deepen that collaboration. He pointed out that cooperation has increased in recent years; as an example, he said that 70% of the initiatives in the 2016 federal budget were included in the Supplementary Estimates (A), 2016–17, which is a significant increase from the previous year. Mr. Pagan mentioned that both departments are working on deepening the coordination of the budgetary and the Treasury Board approvals. Finally, Ms. Baltacioglu highlighted that through this increased collaboration, officials remain nonetheless bound by budget secrecy.

In Australia, Ms. Baltacioglu explained, the Treasury and the Department of Finance work together from the very beginning of policy and program development, which allows the government to table the budget and the estimates at the same time. She noted that Canada should do the same and that it is the federal government’s goal.

1.4 New Deadline for the Main Estimates

As a solution to the lack of alignment between the federal budget and the main estimates, in Empowering parliamentarians through better information TBS proposed delaying the tabling of the main estimates from no later than 1 March to no later than 1 May, so that these estimates would be prepared after the federal budget and would include budget measures. According to TBS, this “would facilitate a more coherent presentation of information to Parliament through the Budget and Main Estimates.” This delay required changing the Standing Orders of the House of Commons. However, in response to some parliamentarians’ concerns (explained in the next section), the new deadline for the tabling of the main estimates was revised to 16 April for the duration of the 42nd Parliament.

In response to questions, Minister Brison explained that the main estimates are subject to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons, while the federal budget is exclusively the purview of the Minister of Finance. Therefore, the President of the Treasury Board can, in conjunction with Parliament, delay the tabling of the main estimates, but has no control over the federal budget. Mr. Pagan added that the Department of Finance requires flexibility regarding the timing of the federal budget to take advantage of the best available information in setting the economic forecasts. This is why, over the last 10 years, there have been variations in the timing of the federal budget. Minister Brison echoed this view by stating that “any government needs to maintain a certain level of flexibility to introduce a budget if there's an external shock to the economy.”

However, Mr. Askari referenced the Committee’s 2012 report on the estimates process, in which it was recommended that the government present a budget on a fixed date, and said he saw no reason for not doing so. He added that fixing the date for the tabling of the main estimates, without doing the same for the federal budget, creates a challenge for aligning the two documents.

Mr. Pagan explained that tabling the main estimates by 1 March only allows the document to reflect Treasury Board funding decisions made up to the end of January. Although there are no requirements as to the date for the tabling of a federal budget in the Standing Orders of the House of Commons, the Financial Administration Act or the Constitution Acts, 1867 to 1982, Mr. Pagan pointed out that the federal budget is usually tabled between mid-February and mid-March; therefore a 1 March deadline “precludes any ability to reflect budget items in the main estimates.” He added that “[t]his in itself presents a fundamental challenge and incoherence in terms of understanding the budget and estimates process.”

Some witnesses described the potential benefits of delaying the tabling of the main estimates. For example, Mr. Pagan, said that it could result in a more coherent sequencing of the documents, a timelier implementation of budget spending measures, the ability to reconcile the main estimates to the federal budget, and the possibility of eliminating a supplementary estimates exercise in the spring. He also said that the costs associated with the changes would be negligible. Mr. Smith commented that aligning the federal budget and the main estimates would be an advantage for the government, as it could implement initiatives earlier in the fiscal year.

In Mr. Leswick’s view, aligning the government’s spending plans and making the federal budget and estimates coherent would require that a substantive costing of new initiatives be completed before they enter the budget process. This could reduce the turnaround time between budget approval and Treasury Board approval, and allow new budget measures to be included in the main estimates. He commented that “the system is nimble enough to start to establish more discipline up front so that when new programs and initiatives are brought into the budget process, they have some sort of substantive costing attached to them.” He added that delaying the tabling of the main estimates might allow budget measures to be included in the main estimates, but only if the federal budget is presented early enough.

1.5 Temporary Changes

“The ultimate coherence is the benefit or the ability to table a budget document and an estimate document that are inclusive and linked.”

Nicholas Leswick, Assistant Deputy Minister, Economic and Fiscal Policy Branch, Department of Finance 14 June 2016

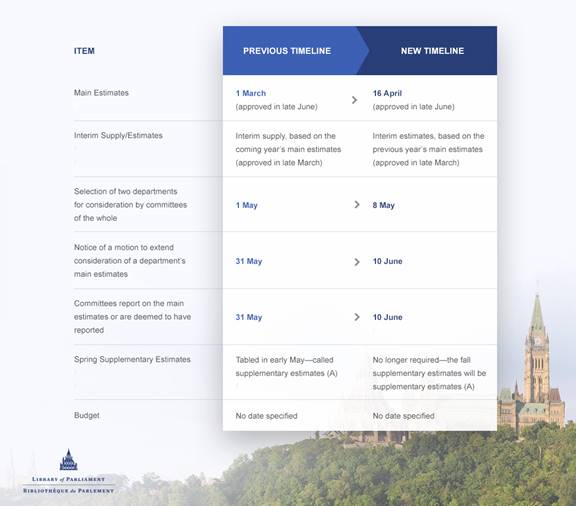

Some parliamentarians and stakeholders voiced concerns that delaying the tabling of the main estimates would weaken parliamentary oversight, as less time would be available to study them. As a result, the deadline for the tabling of the main estimates was temporarily changed to no later than 16 April, from the originally proposed 1 May, for the duration of the 42nd Parliament. On 20 June 2017, the House of Commons adopted a motion which contained amendments that:

- change the timing of the tabling of the main estimates from on or before 1 March to on or before 16 April;

- extend the period for standing committees to review the main estimates from 31 May to 10 June;

- extend the timeline for the Leader of the Opposition to select the main estimates of two departments for consideration by a Committee of the Whole House from 1 May to 8 May, as well as the associated timeline for the consideration of these estimates by a Committee of the Whole House; and to give notice of a motion to extend the consideration of a department’s main estimates from 31 May to 10 June;

- change the references from “interim supply,” which are based on the coming fiscal year’s main estimates, to “interim estimates,” which are based on the nearly completed fiscal year’s main estimates; and

- refer interim estimates to standing committees for their consideration and which shall report not later than three sitting days before the final sitting or the last allotted day in the period ending not later than 26 March.

Figure 2 presents those temporary changes.

Figure 2—Changes to the Parliamentary Financial Cycle

In response to a question, Mr. Pagan confirmed that delaying the tabling of the main estimates has no impact on the number of allotted supply days in the House of Commons, as these are negotiated by the government and the opposition.

Commenting on the temporary changes, Mr. Fréchette said that “alignment could be extremely difficult if there is no change of culture inside the public service itself in terms of providing data”, and that he does not see what incentive would lead to that change, especially in the context of a two-year changeover. Minister Brison acknowledged that “[i]t does take time to change processes and cultures within government broadly, but also within departments and agencies.” He clarified, however, that the new timeline would drive a much closer working relationship between the Department of Finance and TBS, which would result in a closer alignment between the federal budget and the main estimates.

1.5.1 First Fiscal Year under the Temporary Changes

Fiscal year 2018–2019 is the first fiscal year under the new process, with the deadline for the tabling of the main estimates for that year set at 16 April 2018. In addition to the main estimates, the government also presents supplementary estimates. Before the temporary changes, the government used to present three supplementary estimates during the fiscal year—in May, November and February—for unanticipated spending needs or measures announced in the federal budget. The supplementary estimates are each designated by an alphabetical letter. Like the main estimates votes, supplementary estimates votes are referred to House of Commons standing committees for consideration and must be approved by Parliament before the end of the relevant supply period. Due to the temporary changes, the spring supplementary estimates were eliminated. Therefore, the first supplementary estimates in fiscal year 2018‑2019 were tabled on 24 October 2018 and designated with the letter A.

The U.K. government has also reduced its number of supplementary estimates and currently only has one. According to Michael Sunderland, Acting Deputy Director, Government Financial Reporting, Her Majesty's Treasury, this reduction was done to diminish the administrative burden and to make the process more efficient. He added that having only one opportunity to ask Parliament to change the total expenditures after the main estimates put the onus on departments to carefully plan and use their resources.

The federal government needs funds with which to operate from the beginning of the fiscal year on 1 April until Parliament approves the main estimates at the end of June. Previously, funds were allocated through the interim supply process, which usually gave organizations three twelfths of the amounts presented in the main estimates for the coming year. With the new timeline for the main estimates, Parliament approves funding for the first three months of the fiscal year during the supply period ending 26 March through interim estimates, which “are based on the previous year’s main estimates, with adjustments, and referred to committees for review.”[6] In October 2016, Mr. Pagan explained that this is due to the fact that the main estimates would not yet be tabled.

Mr. Jacques explained that interim estimates are prepared in December of the preceding year, according to the TBS internal guidelines, which means that it would be challenging to base them on the current year’s main estimates. Mr. Pagan assured the Committee that TBS would work with departments and agencies to identify specific funding needs in the first three months of the fiscal year and would adjust the amounts presented in the interim estimates accordingly.

However, according to Mr. Smith, that the funds provided to departments and agencies for the first three months of the year will not be based on spending of that fiscal year put parliamentarians at a disadvantage. Interim estimates are referred to standing committees for review, but as noted by Mr. Smith, it could be challenging to question ministers and officials on them when the information is about the expiring fiscal year.

1.6 Other jurisdictions

Minister Brison and his officials referred to the Australian model as a gold standard. Like Canada’s Parliament, the Australian Parliament is bicameral. It is composed of a House of Representatives and a Senate.

The budget policy division within Australia’s Treasury provides the Treasurer with advice on the fiscal outlook and the budget strategy; preparation of the estimates according to external accounting standards; and management of the balance sheet. The division also advises the Treasurer on appropriate budgetary reporting arrangements and has responsibility for ensuring that the budget and other fiscal reports are prepared in a timely and efficient manner. Governance & APS Transformation within Australia’s Department of Finance consolidates budget updates and contributes to the preparation of the budget statements. The text box below describes the Australian model.

Australia’s Budget Cycle

Australia’s fiscal year starts 1 July and ends 30 June, while its budget cycle begins ten months prior to the start, in September. The budget cycle contains several elements, and the main ones are described below.[7]

Before the Fiscal Year

As stated, Australia’s budget cycle usually starts in September when the Treasurer (the member of Cabinet responsible for presenting the Commonwealth Budget to Parliament) and the Minister for Finance provide a submission to the Cabinet on the process and timetable of the forthcoming budget.

In November, the three central agencies (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Treasury, and the Department of Finance) review all proposals submitted by portfolio ministers before they are vetted by the Strategic Priorities and Budget Committee, which is composed of the Prime Minister, the Deputy Prime Minister, the Treasurer, and the Minister for Finance.

During January and February, portfolio ministers prepare their respective submissions along with complete costings for the proposals that are agreed to by the Department of Finance. The Department of Finance prepares a “Green Brief” for each submission, which summarizes the proposal, provides all available information on the proposed measure, and includes the Department of Finance’s perspective.

In March, the Expenditure Review Committee (ERC), a sub-committee of Cabinet,[8] decides which proposals will get funding and their respective level of funding. In April, all the decisions made by the ERC on the new proposals are discussed and considered by the full Cabinet.

The budget is presented simultaneously by the Treasurer to both houses of Parliament on “Budget Night,” which is traditionally the second Tuesday in May. It is important to note that there is no fixed budget date in law, regulation or parliamentary rule. Parliament has less than two months to scrutinize and to approve the budget before the new fiscal year starts.[9] Stein Helgeby, Deputy Secretary, Governance & Australian Public Service (APS) Transformation, Department of Finance, Australian Government, explained that Australia’s appropriations and estimates are fully integrated and that one set of documents is produced and presented on budget night.

During the Fiscal Year

Since funding requirements can change after the budget is presented in May because of new policy commitments from the government or following a reassessment of funding requirements from the agencies, the government can provide additional funding through the additional estimates process, which starts around November of the budget year.[10]

After the Fiscal Year

In September, the Final Budget Outcome (FBO) that contains the general government sector fiscal outcomes for the financial year is tabled for the year that ended on 30 June. Under the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998, the Treasurer “has to release publicly and table an FBO report for each financial year no later than three months after the end of the financial year.”[11]

As noted in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) paper, Rationalising government fiscal reporting: Lessons learned from Australia, Canada, France and the United Kingdom on how to better address users’ needs, several countries around the world, including Canada, have undertaken budget and financial management reforms over several decades to “modernise, enhance accountability and improve decision making in the public sector.” Even the Australian appropriation framework, which is considered by many as the gold standard of public financial accountability, was described as being very complex by Mr. Helgeby. According to him, there is room for further simplification and streamlining of the Australian appropriation framework. He added that “the problem everyone has in the system now is how to really look through the volume to look to those things that really matter.” In his view, the challenge is to follow through with the information presented. Therefore, the Australian government is focusing on tightening up “the relationships between different types of information to make it more useful to Parliament and to the people.”

Mr. Sunderland explained that “most countries are trying to strike a balance that enables them to have firm control over their public expenditure while providing some rigorous transparency to their parliaments for the expenditure they've undertaken.” He noted that parliamentarians have different needs and levels of expertise. While detailed financial reports, budgetary proposals and estimates might be useful to some parliamentarians, others could find the information far too detailed and impenetrable. A challenge faced by the U.K. and other countries is to present highly technical financial information in a way that is easily digestible for parliamentarians who have no financial background and limited time to analyze fiscal reports. He added that the U.K. government produces a high volume of financial information to be as transparent as possible, but that it comes with a risk of overwhelming parliamentarians.

Greg Orencsak, Deputy Minister, Treasury Board Secretariat of Ontario, told the Committee that accountability and transparency are fundamental to Ontario’s financial reporting practices. He stated that this was achieved through reporting that is both regular and consistent. He highlighted that “[a]ccountability and transparency is not an end state; it's something we are always looking to build on and improve to respond to the demands and requirements of the public and the legislature.” Chris Giannekos, Associate Deputy Minister, Infrastructure Plan, Ministry of Infrastructure of Ontario,[12] said that the introduction of a financial accountability officer has added transparency to Ontario’s estimates process. This officer comments on provincial financial documents in a similar way to what the PBO does at the federal level.

Stephenie Fox, Vice-President, Standards, CPA Canada, commented that — in contrast to the federal government — at the provincial level, the budget and the estimates are mostly prepared by the same department. Although this is not the case in Ontario, Mr. Orencsak indicated that Ontario’s Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat have a long history of collaboration both in the development and implementation of the government’s fiscal plan. He commented that in Ontario, the estimates are developed in conjunction with the budget process. Mr. Giannekos added that “the synchronization between the estimates and the budget relies on a very in-depth collaboration between the two organizations … It is very integrated. It is not a relay sort of arrangement, but an arrangement that takes place together throughout the whole year.”

1.7 Striking the Right Balance

Some witnesses made the point that it is crucial to strike a balance in the way information is communicated to parliamentarians. That is, the information must be both detailed and easily understood.

Mr. Leswick conceded that Canadian public servants struggle to make the estimates user-friendly. According to Minister Brison, “[e]very member of Parliament, and Canadians in general, should understand a process that is simple and is easier to understand. The process should be something that we can describe to any Canadian, both in terms of the sequencing and departmental reports.” He indicated that the current system is not designed to be understood and that change is required to strengthen parliamentarians’ ability to hold government to account on its spending.

Mr. Pagan observed that on many occasions parliamentarians have said that “they are unable to perform their role of examining the estimates to ensure adequate control.” He blamed the “incoherent nature” of the budgetary process, which leads to budget measures not being included in the main estimates. He added that “[e]stimates funds are hard to understand and reconcile, and reports are neither relevant nor instructive.”

Mr. Ferguson informed the Committee that through performance audits his office has identified the need to make more information available to parliamentarians as part of the estimates process. He explained, as an example, that in the “Chapter 3—Interest-Bearing Debt” of the Spring 2012 Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, the OAG recommended that the unfunded pension liability of public sector pension plans be reported more comprehensively in the estimates documents. He reported that the government listened to his recommendation and has started to do so. Finally, he added that the main estimates should present the entire financial requirements of federal organizations, including the funds they request for their expenses and their projected revenues[13] during the fiscal year.

1.8 Next Steps

Minister Brison explained that federal departments need flexibility and time to implement the changes to the estimates process, as the federal government is a large, complex group of organizations and it will take at least a couple of budget cycles to realize the full potential of the changes. He also said that “[a]s the departments become accustomed to this new timing and sequencing, there will be a tightening of budget and estimates timing over time that will operationalize as a result of greater efficiency.” In the same vein, Ms. Baltacioglu said that the first federal budget under the new timeline would be a catch-up and that 2019 would be the “first and only year to get the whole system aligned and work the kinks out of it.”

The OECD publication, Legislative capacity to ensure transparency in the budget process, reports that the vast majority of OECD countries approve the budget prior to the start of the fiscal year. The OECD best practices for budget transparency state that the budget should be tabled no less than three months prior to the beginning of the fiscal year. Mr. Smith said that, according to these best budgeting practices, Parliament should vote on the budget prior to the fiscal year before the government begins to spend funds and it becomes difficult to make changes.

Minister Brison indicated that he would like to see the main estimates tabled by 1 April, and that his gold standard is the Australian model, where the budget and the estimates are presented concurrently. In June 2017, Mr. Askari said that the government had not presented a plan to parliamentarians explaining the steps TBS will take to align the federal budget and the main estimates.

1.9 Committee Observations and Recommendations

The Committee notes that the government has introduced significant changes in an effort to make financial reporting more transparent and easier to understand. For example, it has included additional accrual accounting information in some of its financial reports; is has begun reconciling the estimates and the federal budget by including detailed supplementary tables that link budget measures with planned estimates; and it has taken steps to better align the timing of the federal budget and the main estimates.

The Committee agrees with the witnesses it heard that the estimates process is very complex and that it needs to be simplified so that it can be easily understood by parliamentarians from various backgrounds as well as the Canadian public. It encourages the federal government to find ways to simplify the process while emulating the best practices implemented in other jurisdictions, including Australia, and ensuring that the process remains transparent so that Parliament can properly scrutinize government spending plans. It believes that closer collaboration and cooperation between the Department of Finance and the Treasury Board Secretariat is required for the federal budget and the main estimates to be presented at the same time. The Committee encourages the federal government to explore the integration of the Cabinet budgetary approval and Treasury Board submission processes.

The Committee recognizes that there are various independent resources, including the Library of Parliament, the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, and the Office of the Auditor General of Canada to help parliamentarians and the Canadian public understand, scrutinize and analyze the estimates and related documents.

While the Committee agrees that the federal budget and the main estimates should be fully aligned, it believes that Parliament’s ability to scrutinize the government’s taxation and spending plans should not be reduced, as parliamentary oversight is essential. Therefore, parliamentary committees and committees of the whole must have sufficient time to study the main estimates.

The government temporarily put in place, for two cycles, a new deadline for tabling the main estimates and other changes to the estimates process. This will allow the Department of Finance and the Treasury Board Secretariat to determine if these temporary changes will enable Treasury Board to approve budget measures in time for them to be included in the main estimates. It will also allow parliamentarians to ensure that the changes do not affect their ability to scrutinize government spending. However, some members expressed concern that the temporary changes would undermine parliamentary scrutiny of the government’s spending plans.

Since the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates has a mandate to study the process for considering the estimates and supply and the format and content of all estimates documents, among other things, it is best suited to study changes made to the estimates process. The Committee therefore believes that it should study the impact of the new timeline for the tabling of the main estimates before the changes to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons are made permanent.

Although the President of the Treasury Board and his officials stated that the Australian estimates process represents the gold standard, since their budget and estimates are presented concurrently, they did not explain to the Committee how Canada would implement an estimates process similar to Australia’s.

Moreover, the Committee believes that the Department of Finance and the Treasury Board Secretariat should work together to integrate their processes so that budget measures can obtain Treasury Board approval before they are included in the main estimates.

Consequently, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the House of Commons refer the impact of the budget implementation vote, the new timeline for the tabling of the main estimates, and the temporary changes made to the Standing Orders of the House of Commons to the Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates for review before making the changes permanent.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada present a concrete and detailed plan to table the budget and the main estimates concurrently, with consistent information.

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada reform its processes so that Cabinet and Treasury Board approval of budget measures are done in tandem in order for these measures to be included in the main estimates and to ensure the alignment of the budget and the main estimates.

CHAPTER 2: A NEW CENTRAL BUDGET IMPLEMENTATION VOTE

“In a perfect world, all the measures in the budget would be fully and perfectly aligned with the main estimates, as is the case in Australia, where Parliament's approval is very easy and transparent.”

Jean-Denis Fréchette, Parliamentary Budget Officer, 8 May 2018

2.1 Budget Implementation Vote

In its 2017–2018 Departmental Plan, TBS indicated that it planned to include all (100%) budget initiatives in the next available estimates by 31 May 2018. As the 2018 federal budget was tabled on 27 February 2018, the next available estimates were the main estimates for 2018‑2019, which were tabled on 16 April 2018. To reach that target and align the federal budget and the main estimates, a new central vote was introduced in the main estimates for 2018‑2019 “Vote 40—Budget Implementation” in the amount of $7,040,392,000. This budget implementation vote is a central vote managed by TBS and represents the planned spending in 2018‑2019 on initiatives announced in the 2018 federal budget. The vote includes a breakdown of amounts by federal organization, although the amount to be approved by Parliament is the total $7-billion vote. The amounts included in the budget implementation vote were determined through the Department of Finance’s federal budget exercise, with input from federal departments and agencies. Once the budget measures go through the Treasury Board submission process, then the amounts will be allocated from the TBS central vote to individual organizations.

In response to a member’s question about how and when the central Vote 40 was developed, Mr. Pagan explained that the creation of a central vote for budget measures came about after the temporary changes made to the House of Commons’ Standing Orders in June 2017. He added that TBS worked with the Department of Finance to identify options to include all budget measures in the main estimates, but that the 16 April deadline for the tabling of the main estimates limited the number of available options.

In its 2018 budget, the federal government added “Table A2.11—Budget 2018 Measures by Department” as new supplementary information. This table presents financial forecasts for initiatives announced in the 2018 budget broken down by department and agency for the next five fiscal years. The column for 2018–2019 was added as an annex to the main estimates for 2018–2019. In addition, a new table—Sources and Uses of the Budget Implementation vote by Department—was added to the main estimates for 2018–2019. The table presents funding by organization from the 2018 federal budget, including allocated funding transferred from the Treasury Board budget implementation vote to an organization’s votes for operating or capital expenditures, grants or contributions upon approval of the main estimates by Parliament. Minister Brison told the Committee that the new table will be updated every month to reflect the funding allocated to departments and agencies through Vote 40. Since 16 April 2018, the new table has been updated every month and as of 31 October 2018, $2.9 billion had been allocated. Figure 3 shows, in percentage, the funding allocated, withheld and unallocated.

Figure 3—Budget 2018 Measures Funded through the 2018–2019 Main Estimates

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Treasury Board Secretariat, Sources and Uses of the Budget Implementation vote by Department, updated 31 October 2018.

Mr. Pagan explained that when the main estimates for 2018–2019 were tabled on 16 April 2018, Treasury Board had had very few opportunities to approve budget initiatives because of the parliamentary calendar. Treasury Board does not usually meet during parliamentary breaks, which makes it difficult to approve budget measures. The result was that, as of 16 April 2018, only 11 organizations[14] had been allocated a total of $221.1 million for 13 measures under Vote 40.[15] This amounts to just 3.1% of the total $7.0 billion included in the budget implementation vote.

Mr. Pagan went on to point out that part of the funds forecast for budget measures have been withheld for some initiatives, as reported in the Sources and Uses of the Budget Implementation Vote by Department table. According to him, these funds are expenditures that will be made through other authorities, such as statutory expenditures for employee benefits plans or amounts set aside to cover the costs of office accommodation and information technology services. However, statutory expenditures are usually not included in the estimates votes; they are presented in the estimates documents for information purposes only.

Minister Brison said that “[f]or the first time in recent history, the main estimates include 100% of the measures announced in the budget for this year [2018]”. He noted that “[t]his is a major step forward, … made possible, in part, by changing the tabling date of the main estimates to mid-April, after the budget.” According to him, “[a]s a result, parliamentarians now have a document that is relevant and complete, so that they can better hold government to account on how it spends taxpayer dollars.”

However, in his report The Government’s Expenditure Plan and Main Estimates for 2018‑19, the PBO states that

[t]he Government’s approach to funding Budget 2018 initiatives provides parliamentarians with information that only marginally supports their deliberations and places fewer controls around the money it approves.… [v]irtually none of the money requested in the new Budget Implementation vote has undergone scrutiny through the standard Treasury Board Submission process.

Mr. Fréchette said that “[i]n a perfect world, all the measures in the budget would be fully and perfectly aligned with the main estimates, as is the case in Australia, where Parliament's approval is very easy and transparent.”

Furthermore, in his report on the main estimates for 2018–2019, the PBO indicated that “it is unclear that the proposed vote wording would restrict the Government to funding each Budget 2018 measure in the amount set out in the Budget Plan for each Department and Agency, rather than changing the allocations across any initiative mentioned in Budget 2018.” In Mr. Fréchette's view, it is imperative that the wording of a new central vote align with parliamentary procedure, as parliamentarians can only amend a vote by reducing its funding.

Minister Brison indicated that the government is bound by the line-by-line allocations presented in the annex to the main estimates for 2018-2019 and could therefore not exceed these allocations without approval from Parliament. Any additional funding would be requested in subsequent supplementary estimates. He said that to provide clarity, the departmental allocations presented in the annex will be listed in the appropriation bill associated with the main estimates for 2018-2019. Mr. Fréchette supported that initiative. Mr. Askari agreed that adding the allocations contained in the annex to the supply bill would be an improvement. He explained that without it parliamentarians would have voted on the total amount of Vote 40, and the allocations presented in the annex would not have been binding on the government. The appropriation bill for the main estimates, Bill C-80, indicated that the funding was to supplement any appropriation of a department or other organization set out in Annex 1 to the main estimates for the fiscal year 2018–2019, and that the amount given could not exceed the amount set out in the annex.

Moreover, Mr. Pagan informed the Committee that if some funds in Vote 40 are not allocated to departments in fiscal year 2018–2019, they will be frozen and will lapse in the fiscal framework. If the funds are required in subsequent fiscal years, they will be identified in future estimates documents. In response to a question, he noted that unallocated funds from Vote 40 will be considered frozen allocations in the winter supplementary estimates and he provided assurances that those funds will not be reprofiled.

In his report on the main estimates for 2018–2019, the PBO also said that

[u]ltimately, parliamentarians will need to judge whether the Government’s most recent efforts to align the Budget and the Estimates results in an improvement in their oversight role, and if they are willing to accept incomplete information and weaker spending controls to help the Government to expedite the implementation of Budget measures.

Responding to the PBO’s concern that Vote 40 does not allow sufficient oversight by Parliament, Minister Brison commented that “for the first time ever, when MPs are voting on the main estimates they will know, initiative by initiative, where the budget money is going. This is a huge step forward for parliamentary oversight.” Moreover, he assured the Committee that monthly reports will be available on the TBS website showing departmental allocations approved by TBS and remaining balances for each budget initiative. Regarding these reports, Mr. Fréchette noted that they are imperative both for parliamentarians and the PBO to understand how this money is spent.

In defending Vote 40, Mr. Pagan said that TBS administers five other central votes amounting to $5.2 billion for fiscal year 2018–2019. He added that, as opposed to these five central votes, Vote 40 is the only vote that “clearly identifies where the money is going by department, by initiative, and by dollar amount.”

2.2 Parliamentary Committees

After their tabling in the House of Commons, estimates votes are referred to relevant House of Commons standing committees for review. Committees can approve, reduce or reject estimates votes before reporting on them to the House of Commons. During their study of the estimates, parliamentary committees invite ministers and officials from organizations within their portfolios to discuss their estimates. Mr. Ferguson commented that “[p]arliamentary committees play a crucial role in government accountability.” In response to some members’ concerns that ministers should be required to appear before parliamentary committees to defend their estimates, Minister Brison agreed that “[h]aving ministers before committee, when invited to discuss and defend their estimates, is a key part of holding government to account.”

Some members of the Committee were concerned that this new vote totalling more than $7.0 billion is referred to a single parliamentary committee, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates, whereas before the change, budget initiatives were included in organizational votes and referred to different parliamentary committees according to their mandates. Table 1 presents the 10 largest budget measures included in the new $7.0-billion central vote, which illustrates the range of initiatives that were referred to a single parliamentary committee. Even though every parliamentarian had the opportunity to vote on the supply bill, which included the new Treasury Board vote, only a few parliamentarians studied it in committee. On that point, Mr. Pagan argued that all parliamentary committees “can invite officials from any department and ask any questions they want about the estimates process” during their study of the estimates. He added that upon the introduction of a supply bill, any parliamentarian can introduce a motion to reduce or negate an element of the new budget implementation vote.

Table 1—Top Ten Budget Measures and Responsible Organization Included in the New Central Vote

Budget Measure |

Organization |

Amount ($ millions) |

Service Income Security Insurance Plan and other Public Service Employee Benefits |

Treasury Board Secretariat |

554.0 |

Building More Rental Housing for Canadian Families |

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation |

447.2 |

Indigenous Health: Keeping Families Healthy in Their Communities |

Department of Indigenous Services Canada |

408.5 |

Stabilizing and Future Transformation of the Federal Government’s Pay Administration (Phoenix) |

Department of Public Works and Government Services |

306.8 |

Ensuring That Indigenous Children Are Safe and Supported Within Their Communities |

Department of Indigenous Services Canada |

294.8 |

Enabling Digital Services to Canadians |

Shared Services Canada |

278.1 |

Real Property Repairs and Maintenance |

Department of Public Works and Government Services |

275.0 |

Protecting Air Travelers |

Canadian Air Transport Security Authority |

240.6 |

New Fiscal Relationship: Collaboration with Self-Governing Indigenous Governments |

Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development |

189.2 |

Additional Support for the Feminist International Assistance Policy Agenda |

Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development |

160.5 |

Source: Table prepared using data from Treasury Board Secretariat, 2018–19 Sources and Uses of the Budget Implementation vote by Department, updated 10 August 2018.

As explained in the PBO report on the main estimates for 2018–2019, the difference with the new process is that most new budget items are included in the main estimates before the initiatives are fully defined, go through the Treasury Board submission process and are approved by the Treasury Board. Some members of the Committee were concerned that ministers and officials were thus unable to answer specific questions regarding initiatives in Vote 40 during the Committee’s study of the main estimates for 2018–2019. For instance, Matthew Shea, Chief Financial Officer and Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services, Privy Council Office (PCO), said that the $745,000 allocation to PCO in Vote 40 for a new process for federal election leaders’ debates is “a best estimate of what the work will cost in this fiscal year, knowing that the actual methodology of what they're going to do is still being designed.” He added that PCO “do[es]n’t have a plan as to the exact way the money will be spent,” but that it “is an up-to amount that [PCO] would have to justify through a Treasury Board submission.”

Mr. Pagan reiterated that the funds in Vote 40 are up-to amounts, in recognition that Parliament had to approve funds that have not gone through the Treasury Board submission process and therefore for which no plan was yet developed.

2.3 Departmental Plans

The federal government presents departmental plans—previously named “reports on plans and priorities”—at around the same time as the main estimates. They establish the results that departments intend to achieve with the human resources they have and the funding they requested. These plans also provide information on the human and financial resources allocated to each program.

Since all budget measures are presented in the central vote administered by TBS rather than in the votes of relevant departments and agencies, the departmental plans of these departments and agencies did not provide information on budget measures. In his report on the main estimates for 2018–2019, the PBO noted that

[w]hile the Government has included a new Budget Implementation Vote for $7.0 billion, the initiatives to be funded through this vote are not reflected in the departmental plans. Hence, there remains a lack of alignment between the Budget initiatives and planned results.

In a response to a question, Mr. Askari agreed that the fact that budget measures in Vote 40 were not reflected in departmental plans does not favour transparency and accountability. He said, however, that after they are approved, these measures would be discussed in subsequent departmental plans and departmental results reports. Mr. Shea indicated that PCO’s initiative under Vote 40 for the creation of a new process for the federal election leaders’ debates was not part of the agency’s departmental plan because the report was written before the federal budget was approved. Marty Muldoon, Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration Branch, Public Services and Procurement Canada, explained that the department could not report in its departmental plan on budget initiatives in Vote 40 for the department as they were not part of the department’s main estimates. He recognized that fiscal year 2018–2019 was an “awkward transitionary year where not everything has been completely lined up.”

Some Committee members expressed concern that budget measures were grouped together under a single central vote instead of being presented in supplementary estimates and referred to different parliamentary committees according to their mandates. Of particular concern to some members was that budget measures were presented in the main estimates for 2018–2019 prior to being approved by Treasury Board. Furthermore, some members raised the challenge that funds were provided to departments and agencies for these budget measures prior to proper parliamentary examination, and that many of these measures will not be examined in parliamentary committees in the future. Some members of the Committee also pointed out that even if several Budget 2018 measures will be discussed in departmental plans for 2019‑2020, some funds for these measures will have already been spent in the previous fiscal year. Mr. Shea confirmed that “[i]t’s not uncommon for departments to have items that come in after the departmental plan is done, and those items still have outcomes that must be [reported on].” Mr. Pagan pointed out that the new process is not that different from the previous one. Previously, budget items were presented in supplementary estimates and were therefore not included in the departmental plans, as those plans are prepared along with the main estimates. He acknowledged, however, that this “has always been a weakness of our system” that TBS was trying to address.

2.4 Committee Observations and Recommendations

Some Committee members voiced concerns about the new budget implementation vote, including:

- the fact the new vote is only referred to one parliamentary committee;

- other central votes administered by the Treasury Board Secretariat have neither the same scale nor the same content;

- Parliament was asked to approve funds that had not yet gone through the Treasury Board submission process and for which no plans had been developed; and

- new budget measures, all of which are in the budget implementation vote, are not part of departmental plans; therefore, when asked, some ministers and departmental officials could not answer specific questions posed by parliamentarians on these initiatives, as most initiatives had not gone through detailed costing and the Treasury Board submission process.

The new central budget implementation vote was created to ensure that all 2018 federal budget measures were included in the main estimates for 2018–2019, and to better align the budget and the main estimates. The Committee recognizes that fiscal year 2018–2019 is a transition year for the alignment of the federal budget and the main estimates. Therefore, Treasury Board had to develop special tools that would be in place temporarily to reach that objective, and the budget implementation vote was one of them. Going forward, however, the Committee believes that new central votes allocating significant funding to various departments and agencies should only be created in very special circumstances and Parliament should have sufficient time to closely scrutinize them before funds are allocated. The Committee is of the opinion that the government should work towards incorporating budget measures into the votes of relevant departments and agencies in the main estimates. To that end, it encourages the Department of Finance and the Treasury Board Secretariat to work together to establish a timeline that allows budget measures to obtain Cabinet approval and Treasury Board approval, and to be incorporated into the departments’ and agencies’ main estimates votes. It also believes that budget initiatives presented in the main estimates should be supported by information provided in departmental plans that can be scrutinized by parliamentarians.

The Committee understands that Parliament authorizes statutory spending through legislation. Information on statutory spending is included in estimates documents for information purposes only and this spending is not included in the votes. However, the total amount contained in the budget implementation vote that parliamentarians had authorized did include statutory spending.

Consequently, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 4

That the Treasury Board Secretariat work with departments and agencies to ensure that details of new spending presented in main and supplementary estimates appear in their departmental plans as soon as possible.

Recommendation 5

That the relevant standing committees study measures included in the budget implementation vote presented in the main estimates for fiscal year 2019–2020 based on their mandates, and that during the standing committees’ studies of these main estimates, officials from the Treasury Board Secretariat accompany officials from the departments responsible for budget measures to ensure that parliamentarians receive meaningful insight into the new measures and their implementation.

CHAPTER 3: ACCOUNTING FOR APPROPRIATIONS

3.1 Comparing the Estimates to the Federal Budget and the Public Accounts

“Ensuring that the estimates are prepared on the same basis as the budget and public accounts simplifies and improves the accountability provided through the financial cycle of government.”

Stephenie Fox, Vice-President, Standards, Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada), 10 May 2016

Different accounting methods are applied to public financial accountability documents. Currently, the federal budget and the public accounts are presented on an accrual basis, whereas the estimates and related appropriations (or votes) are presented on a modified cash basis. The accounting basis for appropriations is directly linked to how Parliament controls votes for supply.[16] According to Ms. Fox, the government’s financial cycle “plays a major role in fulfilling a public sector entity's duty to be publicly accountable, as long as that information is understandable and prepared on a consistent basis.”

The description below explains the difference between cash-based and accrual-based accounting. According to Mr. Ferguson, “[u]nder the accrual method, financial transactions and other economic events are recorded when they occur rather than only when the entity receives or pays cash.”

Cash-based accounting reports a transaction when cash is received or paid out by an entity. Therefore, financial statement items such as amounts owed to or by the government or other non-cash items are not recorded.

At the other end of the spectrum, accrual-based accounting recognizes a transaction when the activity takes place (the decision) that generates revenue or consumes resources, regardless of when the associated cash is received or paid.

As explained by Mr. Ferguson, the federal government’s financial statements are prepared on a full accrual basis, respecting all of the accounting standards of the Public Sector Accounting Board. According to him, “[d]epartments have no trouble doing accrual accounting.” However, they also need to track their transactions against the estimates, which are currently on a cash basis.

Certain items, such as the acquisition of tangible capital assets, will be reported differently between the federal budget and the estimates. According to Budget 2018,

[u]nder accrual accounting, the cost to acquire an asset is amortized over the expected life of the asset, whereas under modified cash accounting, the cost is recognized as disbursements are made. For example, if a building is acquired that has a useful life of 30 years, then accrual accounting will see the cost amortized over the 30 year life of the asset, while cash accounting will portray the cost only in the first few years when the payments are made.

Mr. Leswick pointed out that "a very detailed reconciliation of expenditure authorities on a near-cash basis and final expenses recorded by departments and agencies on an accrual basis is published each year in volume II of the public accounts.” He argued that the accounting difference between the two documents is minimal. For example, accrual accounting explains only $5 billion of the $66-billion difference between the 2016 federal budget and the main estimates for that year.

While the debate concerning estimates appropriations centres on the choice between introducing full accrual-based accounting methods or keeping the current modified cash-based practice, there is a range of other options involving a mix of cash and accrual accounting methods. For example, hybrid methods such as “modified cash accounting” allow year-end adjustments to recognize some non-cash items like accounts receivable and payable. Alternatively, “modified accrual accounting” follows full accrual principles with one significant departure: it does not recognize capital assets on the statement of financial position. Instead, these assets are recognized fully as expenditures when bought.

3.2 Past Recommendations and Actions

The federal government first launched its strategy to introduce accrual accounting policies and move to full accrual accounting for its budget and financial statements in 1989.[17] After several false starts and investments of over $600 million, it eventually implemented full accrual accounting; for the first time, in 2003, the federal government presented both its federal budget[18] and its summary financial statements[19] on a full accrual basis.

In the past, the Auditor General of Canada, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts and the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates all recommended that the federal government also consider implementing accrual accounting for estimates appropriations.[20] The government responded to these recommendations by doing a study of the issue, which included a comparison of other jurisdictions, and concluded that there was “no compelling evidence to support a move to accrual appropriations.”[21]

However, since that time, the federal government has included additional accrual information in some of its financial reports. For instance, the 2018 federal budget includes detailed supplementary tables that link measures announced in the budget with the planned estimates for the 2018-2019 fiscal year. Table A2.8 provides an overview of the projections for program expenses, on an accrual basis, by major component, while Table A2.12 provides a more detailed outlook for 2018–2019, which includes a full reconciliation of the planned estimates and the budget expenses. According to Budget 2018:

[T]he budgetary balance is presented on a full accrual basis of accounting, recording government revenues and expenses when they are earned or incurred, regardless of when the cash is received or paid. In contrast, the financial source/requirement measures the difference between cash coming in to the Government and cash going out. This measure is affected not only by the budgetary balance, but also by the Government’s non-budgetary transactions. These include changes in federal employee pension liabilities; changes in non-financial assets; investing activities through loans, investments and advances; and changes in other financial assets and liabilities, including foreign exchange activities.

In order to facilitate a comparison with the 2018–2019 main estimates, the 2018 federal budget includes information on budget measures by department and agency on a cash basis:

[T]o further improve transparency and accountability, this budget includes a detailed reconciliation between accrual expenses forecasted in Budget 2018 and the authorities to be reflected in the planned 2018–19 Estimates. Specifically, Budget 2018 includes: (i) a detailed summary table outlining Budget 2018 measures by department on a cash basis (Section 4.1); and (ii) a detailed table reconciling the Budget 2018 expense forecast with the planned 2018–19 Estimates (Section 4.2).

3.3 Benefits and Challenges of Moving to Accrual-Based Estimates Appropriations

Moving to accrual-based estimates could improve decision-making, resource allocations, financial accountability and parliamentary scrutiny.

Ms. Fox noted, “it's very difficult to make the link between the estimates, if they're on a cash basis, to the budget and to the financial statements. If it's difficult to make that link, then it's difficult to understand whether some of the programs are being carried out and how they're being carried out.” According to Ms. Fox, there are benefits to having consistency between planned spending, approved through the estimates, and actual spending, reported in the public accounts. In her view, consistency between the estimates and the public accounts would serve the public interest, increase accountability to the public, and facilitate more informed resource allocation and other policy decisions in government.

In its 2006 report on accrual-based budgeting, the Committee commented that the main advantage of full accrual accounting for budgeting and appropriations is that it makes it possible to measure an organization’s performance by focusing primarily on the management of assets and liabilities and on the full cost of programs and services. Generally, accrual accounting principles encompass all resources management, not only the availability of funds or the short-term cash flow balance. There is also potential for greater transparency and accuracy in government financial documents, which could lead to more effective decision-making and savings in departments.[22]

The 2006 report went on to say that the main disadvantage to adopting full accrual accounting for estimates appropriations in the federal government is that it would be complex, potentially costly, and likely require a lengthy transition period. TBS officials reiterated these arguments during the Committee’s study on the estimates process. They also said accrual appropriations could be confusing for parliamentarians and government officials.

Ms. Fox explained that challenges to adopting accrual-based estimates would include changing the process, ensuring those changes are well understood by all stakeholders, from program managers to elected officials, and changing the culture in the federal public service. She also explained that the current approach of cash-based appropriations is entrenched and familiar, and therefore it would take time and effort if the federal government decides to change to accrual-based appropriations. Martha Denning, Principal, Public Sector Accounting, CPA Canada, agreed that such a transition would require a culture change for the federal government. As well, Ms. Fox noted that some items would not fit the traditional idea of an appropriation, such as depreciation, which represents the effective use of a capital asset over time and is essentially an accounting allocation rather than an expenditure of funds. In her view, these issues can be overcome with time, effort and education, along with the fact that other major jurisdictions have successfully made the switch to accrual-based appropriations.

Ms. Fox explained that “[a]ccrual accounting is about all parts of the balance sheet, not just cash.” She explained, “[a]ccrual appropriations deal with all parts of the balance sheet and the operating statement, including all assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenditures.” She commented that a move to accrual appropriations would improve the management of resources and accountability by providing a more detailed picture of the resources that the federal government is using, as compared to cash-based appropriations. According to Ms. Fox, “[i]t is important to get that fulsome picture to be able to manage all of those resources, not just focus on the cash resource.” She added, “if you’re not focused on an accrual basis, you’re not focused on the long term,” explaining that one of the negative impacts of managing on a cash or short-term basis is that government “end[s] up downloading additional debt or liabilities to future generations as opposed to taking care of some of those and planning for those commitments starting today.”

Mr. Ferguson shared his view that accrual appropriations would be “a much simpler approach,” despite an inevitable transition period. “It means not having to keep track of both the accounting expenses and the expenditures against the main estimates.” According to him, at the end of the day, parliamentarians would need to understand what they are voting on if they were voting on an accrual basis rather than a cash basis. He added that it would also be important for TBS and the government to have appropriate ways to control what is being voted on when using an accrual-basis.

Ms. Denning explained that an appropriation that is accrual-based gives the government the authority to use public resources to achieve a certain result. It involves granting a bigger authority by tying that appropriation to a department that has revenues, expenses and outcomes that are supposed to be achieved because of collecting those revenues and incurring those expenses. Ms. Fox highlighted that cash is only one resource that the government has and that managing appropriations on an accrual basis focuses on all the resources for which a government is responsible. She argued that by only managing on a cash basis, the government is managing for the next year, whereas by looking longer term at the full liability, the government recognizes that a commitment made today has a cost down the road. She cited the example of pension liabilities: on an annual cash basis, the government contributes a certain amount of funds to pension liabilities or to the pensions of its employees, but on an accrual basis, it would be forced to take into account the future costs of those pension liabilities.

3.4 Other Jurisdictions

The governments of British Columbia and Ontario, and the national governments of the U.K., New Zealand and Australia use accrual-based estimates appropriations. According to Ms. Fox, from looking at other jurisdictions, CPA Canada believes that accrual-based appropriations are “a best practice.” Both Ms. Fox and Ms. Denning encouraged the federal government to look at the experiences of these other jurisdictions.

According to Ms. Denning, when CPA Canada looked at other Westminster democracies, it noted that New Zealand had been following this approach the longest, and that their information was easy to understand and follow. She explained that New Zealand requires “all of their departments and agencies to submit their plans on a full accrual basis: this is what we think we raised in revenues; this is what we'll spend; these are the programs that are behind those expenses; this is the outcomes we expect,” and that the government then gives departments and agencies the authority to raise those revenues, incur those expenses, and achieves those outcomes through accrual appropriations.

In the case of Australia, Alan Greenslade, First Assistant Secretary, Financial Analysis Reporting and Management, Australian Government, explained that “[e]verything is run on an accruals basis, and cash [information] is derived from that…. It comes out of the same estimates, the same process.” Lembit Suur, First Assistant Secretary, Governance and Public Management, Australian Government, shared that “appropriation bills going back three or more years are now automatically lapsed, so people's capacity to draw down cash from old [accrual] appropriation authorities issued by the Parliament has been limited.” He explained that this approach is one way of regulating the amount of cash that is held in the system.[23]

According to Mr. Helgeby, the Australian experience has shown that ministers are “more comfortable talking about cash … because it’s an easier concept,” and as such, “much of the public debate … is still focused on the cash version of our numbers.” However, he remarked that “the value of accruals and accrual concepts is in the depth it gives to financial statements and the possibilities it opens up for financial analysis.” He continued, “appropriations for departments are simply about what is the most sensible way by which you get resources to the right place so that people can deliver programs, in such a way that Parliament is happy that it has discharged its responsibilities of ensuring that monies are only taken from consolidated revenue against a proper appropriation.”

In the case of Ontario, Mr. Orencsak shared that “[b]y publishing the budget, expenditure estimates and public accounts all on the same basis, the government is able to clearly articulate not only plans, but also progress relative to these plans.”

3.5 Transition Considerations