HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CHAPTER 1: THE EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE PROGRAM: OVERVIEW, RECENT CHANGES AND RECENT TRENDS IN PROGRAM ACCESSIBILITYA. Overview of the Employment Insurance ProgramThe employment insurance provides temporary income support to workers who have lost their job for reasons not in their control, while they look for new employment or upgrade their skills. The program also provides financial support for eligible self-employed fishers who are actively seeking employment. In addition, temporary financial assistance is made available to workers who are sick; pregnant; caring for a newborn, a newly adopted, or critically ill child; or caring for a family member who has a serious medical condition with a significant risk of death. It also includes measures to promote employment. The program’s parameters are outlined in the Employment Insurance Act and the Employment Insurance Regulations, the Employment Insurance (Fishing) Regulations, and the Insurable Earnings and Collection of Premiums Regulations. The Canada Employment Insurance Commission (CEIC) is responsible for overseeing the Employment Insurance Act and its regulations, while EI program operations are overseen by ESDC and Service Canada on behalf of the CEIC. B. Key Program Changes Since 2012In 2012, the federal government’s Economic Action Plan included a number of targeted changes to EI “to make it a more efficient program that promotes job creation, removes disincentives to work, supports unemployed Canadians and quickly connects people to jobs.”[2] These changes included the following measures:

Another change that drew a great deal of attention, according to Paul Thompson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the Skills and Employment Branch at ESDC, was the expiry of a pilot project that extended EI benefits by an additional five weeks.[8] Changes were also made to special benefits, notably by creating a new special benefit for parents of critically ill children, and increasing access to sickness benefits for individuals receiving parental benefits.[9] Other changes have also been made since then. In 2014, the EI economic regions of Prince Edward Island (PEI), Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut were each divided into two EI economic regions: one for the capital region and one for the region outside the capital. This brought the total number of EI economic regions in Canada from 58 to 62. Access to sickness benefits for claimants of either the compassionate care benefit, or the parents of critically ill children benefit, was also enhanced in 2014. Further, in January 2016, the maximum duration of compassionate care benefits was increased from 6 weeks to 26 weeks.[10] During the course of the Committee’s study, the federal government tabled its budget. Budget 2016 proposes to improve EI, such as expanding access to EI for new entrants or re-entrants, reducing the waiting period for all from two weeks to one week, extending the Working While on Claim pilot project until August 2018, simplifying job search responsibilities for claimants, temporarily extending regular benefits in those regions the hardest hit by rising unemployment, extending the maximum duration of Work-Sharing agreements, and making service delivery more responsive.[11] C. Recent Trends in Employment Insurance AccessibilityFor unemployed individuals, access to EI benefits depends on three conditions: they must have contributed to the EI program within the past 12 months, have a valid reason for job separation, and have worked a sufficient number of hours based on their regional unemployment rate. According to the Employment Insurance Coverage Survey, 2014, there were roughly 1.26 million unemployed Canadians in 2014. Of these, 768,000 had contributed to EI in the previous 12 months, 581,000 met the criteria for valid job separation. Of the latter, 483,000 (or 83.1%) had worked enough hours to be eligible to receive EI. Since not all unemployed persons who are eligible for EI apply for benefits, the EI accessibility ratio (based on the number of unemployed persons receiving EI benefits) is different from the EI eligibility rate (based on the number of unemployed persons who would be eligible for EI, in theory).[12] According to the Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report published by the CEIC, three different measures are used to calculate program accessibility:

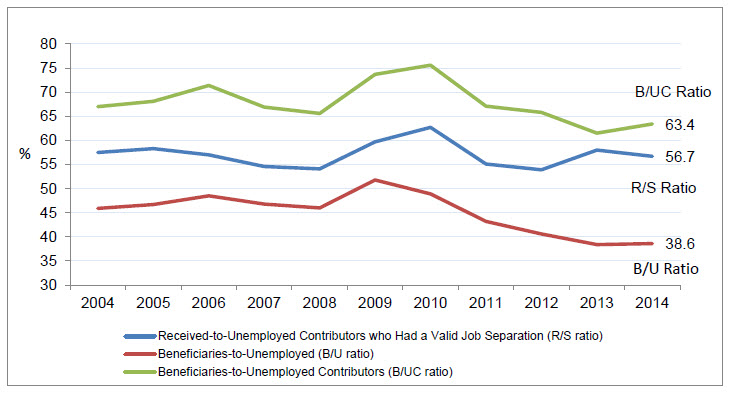

The R/S ratio takes into account unemployed individuals who worked, contributed to EI, and had a valid job separation, while the two other ratios use much broader groups of unemployed individuals.[13] In 2014, the R/S ratio was 56.7%, while the B/UC ratio was 63.4% and the B/U ratio was 38.6%.[14] As shown in Figure 1, trends in accessibility rates vary depending on the measure used. Figure 1 – Employment Insurance Accessibility Ratios, 2004 to 2014 (%)

Source: Table prepared from CEIC data, Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015, Chapter II-2, Chart 21. According to Paul Thompson, various stakeholders have raised concerns that the B/U ratio was only 38.6% in 2014, which means that only 487,000 of the 1.3 million unemployed individuals in Canada received EI benefits that year.[15] Mr. Thompson told the Committee that this ratio “is widely used by some stakeholders as a measure of access to the EI program.”[16] However, he added that it is less well known that approximately 490,000 of the 1.3 million unemployed people (39%) had not worked in the last 12 months, and that only 98,000 unemployed individuals (8%) had insurable employment and valid job separation, but had not worked enough hours to qualify for regular EI benefits.[17] Mr. Thompson also pointed out that the last Employment Insurance Coverage Survey showed that 83% of unemployed people covered by EI (that is, unemployed individuals who contributed to the EI program and who had a valid job separation) were eligible for regular EI benefits in 2014, which was on par with figures from before the 2008–2009 recession.[18] He also said that “we expect to see a slight increase in this eligibility rate as a result of the recently announced measures to expand the eligibility of new entrants and re‑entrants.”[19] [2] Economic Action Plan 2012, 29 March 2012, p. 18. [3] Part of implementing these new definitions included creating three categories of claimants (based on how frequently they use EI) with different requirements for searching for suitable employment. For more information about this change, see: André Léonard, Employment Insurance: Ten Changes in 2012–2013, Publication No. 2013-03-E, Ottawa, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, 23 January 2013, p. 2-5. [4] Ibid., p. 5-6. [5] Ibid., p. 6-7. [6] Ibid., p. 7-8. [7] Ibid., p. 8-9. [8] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 May 2016, 1730 (Paul Thompson, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, Skills and Employment Branch, Department of Employment and Social Development). [9] Ibid. [10] Government of Canada, Canada Employment Insurance Commission (CEIC), Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015, Annex 7.1. [11] Government of Canada, Budget 2016, Growing the Middle Class, 22 March 2016, p. 73 to 77. [12] For more information, see CEIC, Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015, Chapter II‑2, section 2.2.3. [13] CEIC, Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2014/2015, Chapter II-2, section 2.2.3.1. [14] Ibid., section 2.2.3. [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid. [18] Ibid. [19] Ibid. |