HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INTRODUCTION

While there is general agreement that precarious employment is a serious issue, it is more difficult to define and measure precisely what constitutes precarious employment.[1] In addition, there is concern that this lack of clarity around what constitutes precarious employment may be limiting the government’s ability to effectively address the impact it has on workers and their families.[2] As the government seeks to better protect Canadian workers, precarious employment must be considered.

Private Members’ Business M-194, asked the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (the Committee) to conduct a study on precarious employment in Canada.

The Committee held three meetings, hearing from a total of 16 witnesses, and received three briefs. Witnesses included departmental officials, expert researchers, representatives of national non-government organizations and individuals with lived experience of precarious employment.

CHAPTER 1: WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT?

No one is immune to the effects of precarious work… The nature of work is changing, and we need to understand how it impacts our workers so that we can better protect Canadians.

Terry Sheehan, Member of Parliament, Sault Ste. Marie[3]

Background

In recent decades significant changes have taken place in the world of work. This is the result of globalisation, advances in information and communications technologies, the shift from manufacturing to the service sector, significant demographic changes and the desire for flexibility from both workers and businesses.[4] These changes have profoundly affected the competitive environment, the use of technology, skill requirements, contractual work arrangements, scheduling, and in turn, have caused a decline in the full-time standard employment relationship.[5]

In researching this type of patchwork or uncertain employment… I was surprised to see there existed no concrete expressions on what defined precarious work or how we could identify those affected by precarious employment, and most importantly, no organized ideas on what we can do about it…

Terry Sheehan[6]

Even though the term precarious employment is used frequently, there is no universally accepted definition for this concept. Internationally, this is the result of the multidimensional nature of precarious work, which is highly dependent on the region; in particular on the social, economic and political systems as well as labour market institutions in different countries.[7] This also is in large part due to the fact that precarious work is not a single problem but a group of interconnected problems. Finally, this is also due in part because our expectations of precarity are changing over time.[8] Indeed, the nature of precarious employment is a moving target that continues to evolve with the changing economy.

Elements that are associated with precarious employment

Low-wage work

Even though the term precarious employment is used frequently, there is no universally accepted definition for this concept.

Recent research on the quality of employment in Canada highlights periods in which the share of low-paying jobs has increased and decreased.[9] Figure 1 illustrates the share of men and women, aged 25‑34, in low paying jobs from 2007 and 2018 in Canada. The share of male workers in this age group earning less than $15 an hour fell from 17% in 2007 to 15% in 2008. It rose to 16% in 2010 before falling again. Between 2014 and 2018, the share of men aged 25 to 34 earning less than $15 an hour fell from 14% to 12%. This is the lowest this figure has been since 1984, when the share of men 25‑34 earning less than $15 an hour was also 12%.

For women, the story is different. The share of women aged 25 to 34 earning less than $15 an hour has always been significantly higher. In 2007, it was 24%. It fell to 21% in 2009 and then began to rise. In 2014, 22% of women aged 25 to 34 were earning less than $15 an hour. In 2017, the share fell to 18% but rose to 19% in 2018. In contrast to men, in 1984 the share of women aged 25 to 34 earning less than $15 a hour was 30%.

While low-wage employment is partly a story of temporary and part-time employment, it is important to also consider full-time permanent employees who are doing low-wage work. In addition, low-wage workers are more likely to have minimal or no non-wage benefits such as a pension plan, supplementary health, drug or dental benefits or paid sick leave.[10]

Figure 1—Percentage of employees aged 25 to 34 earning less than $15 an hour, 2007-2018, Canada

Source: Survey of Work History of 1981; Survey of Union Membership of 1984; Labour Market Activity Surveys of 1986-1990; Labour Force Surveys of 1997-2018; as found in: René Morissette, Changing characteristics of Canadian Jobs, 1981 to 2018, Economic Insights, Statistics Canada, 2018.

Lower wage jobs tend to be concentrated in certain sectors such as retail and hospitality (accommodation and food services). These sectors tend to employ larger numbers of women in temporary, part-time positions.[11] This is also consistent with recently published work by Statistics Canada which show that some of fastest-growing sectors over the last decade, including the hospitality sector, offered some of the lowest-quality jobs.[12] This is true with respect to not only pay and benefits but other characteristics such as working environment and career prospects.[13]

Non-standard work

Non-standard work refers to working arrangements that fall outside of standard permanent employment. Non-standard work comprises part-time work, self-employment and temporary work. Not all types of non-standard work are associated with precarious employment, but many are. This includes:

- workers with fixed-term contracts (temporary workers);

- workers who work part-time but would prefer to work full-time (involuntary part-time workers); and

- unincorporated self-employed people who do not have paid employees (solo self-employed).[14]

The solo self-employed are often precariously employed because they lack the security that comes with other forms of employment. This group includes so-called ‘independent contractors’ who may otherwise be in an employee-like relationship with an employer but are misclassified by their employer.

In addition to low earnings, these specific non-standard working arrangements are closely associated with occupational health and safety challenges. For example, temporary work is associated with higher accident rates.[15] Workers in non-standard working arrangements are also more likely to be exposed to sexual harassment.[16] Moreover, most social protections (e.g. employment insurance, sick leave, supplementary health and dental benefits, severance, employer pension plans, labour standards protections etc.) have been built around or informed by standard, permanent, full-time employment. As a result, workers with non-standard working arrangements are often excluded from programs and regulations intended to keep people safe, healthy and financially secure.[17]

Moreover, most social protections (e.g. employment insurance, sick leave, supplementary health and dental benefits, severance, employer pension plans, labour standards protections etc.) have been built around or informed by standard, permanent, full-time employment.

Although available statistics are an imperfect measure for precarious non-standard working arrangements, the trends and composition effects of available statistics can provide important insights.[18] Figure 2 shows the trends in non-standard work since 2007 before the great recession. These trends provide a partial picture of the evolution of insecure working arrangements that are closely associated with precarious employment. It is a partial picture because other dimensions of precarious employment are not captured (e.g. low-income, lack of career prospects), but also because these types of jobs may overlap (e.g. a self-employed worker may also be involuntarily working part time), and because these trends sometimes run in opposite directions. There are also sub-sets of workers captured within these more broadly defined variables. For example, a temporary agency worker who hopes that a placement will lead to a full‑time, permanent position will be captured in the same temporary category as a highly skilled, highly paid contract employee who prefers to take temporary contracts because they offer flexibility and variety.

Figure 2—Numbers of People Employed in Non-Standard Work (Solo Self‑Employed, Involuntary Part-Time and Temporary): Persons (in thousands) 15 Years of Age and Over, Canada, 2007‑2018

Source: Figure prepared by the author using data from Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0027-01; Table 14‑10‑0029‑01; Table: 14-10-0072-01 consulted 11 March 2019.

Figure 3 illustrates the trends in the share of non-standard employment. The data indicates that these working arrangements as a share of total employment has remained relatively stable over time. Thus, while the number of workers in working arrangements that are more precarious are growing, their share of total employment has been more stable.[19]

Figure 3—Non-standard work (Solo Self-Employed, Involuntary Part-Time and Temporary employment) as a share of employment, 15 Years of Age and Over 2007‑2018

Source: Figure prepared by the author using data from Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0027-01; Table 14‑10‑0029‑01; Table: 14-10-0072-01 consulted 11 March 2019.

Involuntary part-time work increased for both men and women during the recession. As labour market conditions improved, involuntary part-time employment decreased for women but remained stable for men until 2017. Between 2017 and 2018 the number of men who reported being working part-time involuntarily fell below 300,000 for the first time since the 2008.

Self-employed workers can be entrepreneurs, free professionals, craft workers, those in skilled but unregulated professions and those in unskilled professions. There is, however, an important distinction to make between those well established in self-employment (who tend to be incorporated and have paid employees) and the solo self-employed. In total, self-employed individuals comprise about 15% of the workforce. Solo self‑employed are roughly 8% of the workforce and can be characterized as precariously self‑employed.

Women who were solo self-employed increased (16%) since 2008, while the numbers of solo self-employed men declined slightly. Between 2017 and 2018, women in solo self‑employment is the only major precarious category that actually increased.

Lack of job security is a key risk for those on temporary or fixed-term contracts. Fixed‑term work in certain sectors may offer lower pay than permanent work and a lack of access to employment rights. In 2008, approximately 12.2% of the workforce were in temporary employment. Temporary employment situations for both men and women increased during the recession and have remained stable or increased slightly throughout the recovery until 2017. In 2018, the number of men and women in temporary employment declined. They presently comprise 13.3% of the workforce.

Figure 4 illustrates that the share of temporary employment relative to total employment in Canada is above the OECD average. It is also noteworthy that some OECD countries with very high living standards also have high rates of temporary employment (i.e. Sweden and Netherlands) but in turn these countries also have correspondingly higher levels of social protection programs.[20] In this respect, having more generous social protections (EI, disability insurance, social assistance) can offset some the precarity associated with working arrangements.[21]

Figure 4—Temporary employment as share of total employment, OECD countries, 2017

Source: Figure prepared by Statistics Canada using data from the OECD, Temporary Employment (indicator), 2017.

Additional work arrangements related to precarity

Temporary agency workers are employed by a temporary employment agency or “temp agency”, and then hired out to perform their work on the premises and under the supervision of another organization.[22] As a result, these workers are in a triangular relationship with both the “temp agency” and the client organization. As noted above, workers who find placements or contracts will be captured in the labour force data as temporary workers. However, “temp agency’’ work often relies on more vulnerable groups, such as young workers, especially for jobs with low training costs. Research suggests that there is a lack of trade union organisation in this segment of the labour force and that workers may have limited knowledge of their rights or the means to apply them.[23]

In addition, there is a risk of precariousness in terms of earnings for “temp agency” workers if they receive lower wages than comparable workers, in order to balance the fees paid to the agency. Agency workers are generally perceived as temporary labour, even if they work in a company for a long time, and consequently they may not profit from a range of company benefits. There is however, evidence that “temp agency” work can potentially act as the first step for unemployed individuals, including recent immigrants, making their way into the labour market and on to permanent work.[24] In addition, there is evidence that ‘’temp agencies’’ play an important role in public sector staffing including the federal public service.[25]

Recent research from Statistics Canada highlights that smaller firms have higher incidence of part-time and temporary employees. In Canada, about one in three temporary and part-time workers worked in enterprises with fewer than 20 employees. Only one in five workers in enterprises with fewer than 20 employees were employed on a full-time, permanent basis.[26]

It stands to reason that small enterprises hire more part-time and temporary workers. These types of arrangements are often less costly and more flexible for small firms that may have to cope with fluctuations in demand. Moreover, part-time and temporary positions may be used as a screening process to determine if a worker is the right fit.[27] However, many small enterprises lack features and non-wage benefits that make employment more secure and income less precarious. These include: unionization; health, drug and dental benefits; pension benefits; and training and career advancement opportunities.[28]

New technology has enabled new forms of work in what is often referred to as the platform or gig economy. It is having an impact on the precariousness of work in some sectors. The platform or gig economy is associated with the growth of self-employed, freelancers, and micro-entrepreneurs working either full- or part-time. These short‑term work arrangements are made possible by digital platforms, the most high-profile examples of which are in the transportation sector. Companies such as Uber and Lyft use new technology to coordinate drivers and passengers. However, there are other online based platforms such as Amazon Mechanical Turk, Upwork, TaskRabbit, that connect workers with customers. These online platforms can offer flexible opportunities but are a challenge to regulate. Many of these workers operate outside of the Employment Insurance (EI) or Canada Pension Plan (CPP) systems.[29]

Internships are viewed as a way of providing young people as well as recent immigrants with work experience and enabling them to gain a foothold in a particular occupation or sector, or with a certain employer, allowing them to move on into the wider labour market. There are concerns that these types of contracts can be abused: individuals working on these contracts may be paid very low wages, or no wages at all. There has been growing controversy related to unpaid internships, in part because they can be a source of precarity for many young or vulnerable workers. Interns may also not be aware of their employment rights and therefore at risk of abuse, in areas such as long working hours without respite periods. There is also a risk that job quality may be low, in terms of control over the content, skills that are learned and the types of tasks performed. There are also concerns that interns are not being offered training, but rather are less expensive form of labour.[30] At present, there is not reliable data on the prevalence of internships (both paid and unpaid) in the labour market.[31]

There are a range of types of undeclared or “under the table’’ work. These workers are typically referred to as informal workers. Workers engaged in this type of work are at high risk of precariousness. They are at risk of low pay, depending on the type of work. However, one of the main risks is the fact that they are not paying tax, EI premiums or CPP premiums, which means that they will not be entitled to social security coverage. While avoiding these contributions is often illegal on the part of both the worker and the employer, this does not diminish the employer’s obligations related to employment standards, including minimum wage and workers compensation, as well as occupational health and safety protections. Because informal workers are also ‘under the radar’ in terms of these protections, they are at greater risk of exploitation.[32] Undocumented migrants are an important and particularly vulnerable subset of informal workers.

Temporary foreign workers are workers that employers have been allowed to hire through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program.[33] This program allows employers to hire foreign workers to fill temporary jobs when qualified Canadians and permanent residents are not available. Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) through its Service Canada processing centres, assesses applications from employers requesting permission to hire temporary foreign workers and conducts an assessment to determine the likely effect these workers would have on the labour market.[34]

Certain vulnerable workers are more likely to have precarious employment

Recently released Statistics Canada research documents that women, youth, seniors, and workers without post-secondary education are more likely to be working part-time or temporary jobs. This may be either by choice or as the result of difficulty accessing standard employment. In 2016, about one-third of young Canadian workers were in part-time jobs, while this was the case for one-tenth of prime-age workers (ages 25 to 54). High rates of part-time work were also observed among seniors (31%), women (26%) and workers without post-secondary education (25%). Overall, their risks of falling into the poorer job quality classes were notably high: about 38% for women and for 18‑ to-29-year-olds, and 34% for seniors and workers without post-secondary education.[35]

Research commissioned by the Law Commission of Ontario further identifies recent immigrants, those who have been in Canada less than 10 years, as being significantly more likely to be working in precarious jobs.[36] The report also notes that there is a slightly higher proportion of visible minorities working in precarious jobs.[37]

There are important differences between sectors

Several witnesses told the Committee that certain sectors will be more precarious than others. Further, some sectors are becoming increasingly precarious as skills change and as work performed is either automated or outsourced.[38]

The increases in temporary, solo self-employment and part-time work, reflects an ongoing shift in the relative importance of goods-producing industries to service-producing industries.[39] Parisa Mahboubi of the CD Howe Institute noted that the share of temporary employees in service industries has climbed from 76% in 1997 to 83% in 2018.[40]

Within the services sector, an increasing proportion of jobs are in accommodation and food services, retail and the education sector. Yet, accommodation, food services and retail pay some of the lowest wages.[41] With respect to the education sector, while hourly wages are above the Canadian average, the average number of hours worked in that sector are by far the lowest of any sector.[42]

Figure 5 illustrates the share of non-standard work arrangements (temporary, part-time, and solo-self employed) in manufacturing and in professional, scientific and technical services for the years 2007 and 2018. The share of non-standard work arrangements in manufacturing has consistently represented about 10% of the workforce in manufacturing. In contrast, those in non-standard work arrangements have consistently represented about 35% in professional, scientific and technical services.

Figure 5—Contribution of non-standard employment to total employment, 2007 and 2018, selected industries

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, custom tabulations.

What is important here is that total employment in manufacturing is declining while employment in professional, scientific and technical services is increasing. Figure 6 illustrates the number of employees in manufacturing sectors and the professional, scientific and technical services between 2007 and 2018. The number of employees in manufacturing declined from 2 million to 1.7 between 2007 and 2009. It remained stable until 2018. In contrast, the number of employees in scientific and technical services increased steadily from 1.1 million in 2007 to 1.5 million in 2018.

Figure 6—Total employment, selected industries, 2007-2018

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0202-01.

Dimensions of precarity

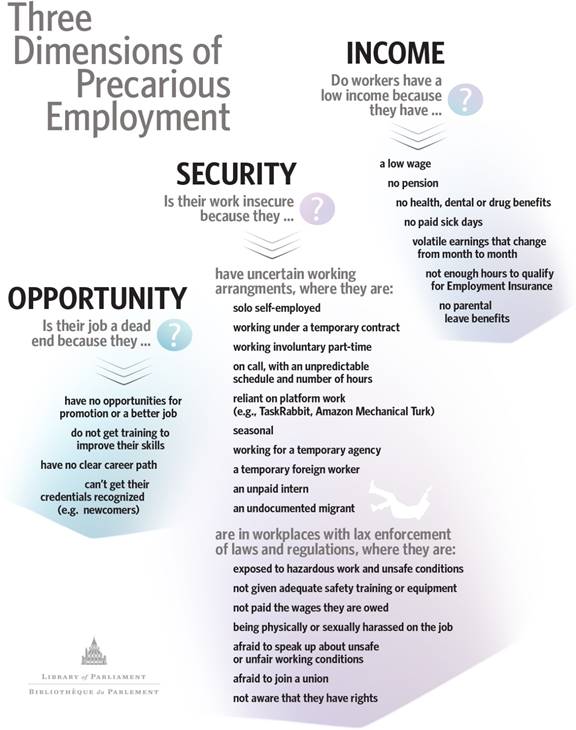

The International Labour Organization (ILO)[43], European Union[44] and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)[45] have advanced frameworks to better understand precarious employment. In general, these frameworks propose broad dimensions that organize different components of precarious employment in a way that can be adapted to different contexts. Though these frameworks continue to evolve and may require more precision in particular contexts, using broader dimensions to identify and organize the characteristics related to precarious employment (e.g. low wage work, involuntary part-time work arrangements, higher risks of employer misconduct, temporary contracts, uncertainty around future income, etc.) contributes to our and understanding and helps to more precisely measure and address the problem.

Income, security and opportunity

In the Canadian context, organizing dimensions of this framework could include:

- low-income;

- lack of security (both job security and security related to health and safety and the security to assert their rights); and

- lack of opportunities (both opportunities for career advancement but also opportunities to engage in different work or work arrangements).

Figure 7 illustrates these three dimensions and indicates where many of the elements associated with precarious employment described above are situated. Sometimes an element belongs in more than one dimension. For example, involuntary part-time work falls into insecure dimension (often the first to be let go during a business downturn) but it also can be in low-income (not getting enough hours to qualify for EI).

Figure 7

Organizing the elements associated with precarious employment around these dimensions and mapping different intersections can help to more precisely articulate the scope of precarious employment. This, in turn, can better inform both our understanding of the problem and the policy tools needed to address it.[46] It recognizes and addresses the need for clarity while understanding that defining precarious employment for the purpose of collecting data is different from defining precarious employment for the purpose of modernizing employment standards regulation, or the purpose of developing income security programs.[47]

What tools does the federal government have to address precarious employment?

Broadly speaking, the federal government’s tools to address precarious employment can be grouped into four categories, described below:

- income support programs;

- regulation through the Canada Labour Code;

- the federal government as a model employer; and

- skills training.

Figure 8 illustrates the dimensions and elements of precarious employment and maps them to these different policy tools that the federal government has to address the issues.

Figure 8

Chapter 2: What can be done to make employment less precarious? will explore in greater detail through witness testimony how these policy tools can address the dimensions of precarious employment: low income, lack of security and lack of opportunities.

Income support programs

ESDC is the main federal department responsible for income support programs which include Employment Insurance (EI) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS).[48] It also assists workers in obtaining and maintaining employment. Additional income support programs are delivered through the income taxation system. These programs include the Canada Workers Benefit (formerly the Working Income Tax Benefit) and, the Canada Child Benefit. Finance Canada is responsible for the policy underlying such benefits, and responsibility for their administration rests with the Canada Revenue Agency.[49]

Employment Insurance and the Guaranteed Income Supplement

EI is a social insurance program funded by employee and employer contributions on insurable earnings. It provides temporary financial assistance to workers who have paid into the program and have lost their job. Workers receive EI benefits only if they have paid premiums in the past year and meet qualifying and entitlement conditions.[50] It is noted that Budget 2019 introduced a number of proposed changes to the EI program, including the introduction of an EI Training Support Benefit.[51]

EI benefits are also available to workers who have paid into the program if they are sick, pregnant or caring for a new-born or newly adopted child, as well as to those who must care for a family member who is seriously ill with a significant risk of death, and to those who must provide care or support for a critically ill or injured family member.[52] Self‑employed workers can also access EI special benefits by entering into an agreement, or registering, with the Canada Employment Insurance Commission.[53]

The GIS is a monthly non-taxable benefit to Old Age Security pension recipients who have a low income and are living in Canada. The amount of the GIS a person receives is determined by their marital status and the previous year's income (or in the case of a couple, their combined income). At present there is a $3,500 GIS earnings exemption that encourages low-income seniors who are willing and able to participate in the labour force. This exemption effectively reduces the level of earned income used to calculate GIS allowing low-income seniors to earn a specified amount of income before triggering a reduction in benefits. Budget 2019 proposes the introduction of legislation that would extend eligibility for the GIS earnings exemption to self-employment income; increase the full exemption to $5,000; and introduce an exemption of 50% for up to $10,000 of annual employment or self-employment income beyond the original $5,000.[54]

Working Income Tax Benefit—Canada Workers Benefit and Canada Child Benefit

The Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB) was a federal refundable tax credit introduced in 2007 for low-income individuals or families with earned income over $3,000. It is intended to support low-income workers with additional income and incentivize continued participation in the labour force. In January 2019, the WITB was renamed the Canada Workers Benefit (CWB). The benefit rate, the maximum benefits under the program, and the maximum disability supplement were increased.[55]

The Canada child benefit is a tax-free, means tested monthly payment made to eligible families to help them with the cost of raising children under 18 years of age. The amount of the benefit is calculated using information from income tax return and is reduced using a phase out rate based on family income and number of children.

Skills training and education

Training through Employment Insurance

A range of supports for training are available at the federal level through the EI program. EI claimants are permitted to take training at their own initiative while they are receiving benefits, provided they declare their training and can prove they are still willing and able to work and are continuing to look for a job. EI claimants can also undertake training with permission from their provincial or territorial government, or from an Indigenous organization that provides employment programs in their province or territory. In addition, with the approval of Service Canada, EI claimants who have lost their job after several years in the workforce may be permitted to undertake full-time training without being required to continue looking for work while in school.[56]

In addition, Budget 2019 proposes a new non-taxable Canada Training Credit and leave provisions to protect workers’ entitlement to take time away from work to pursue training. The Canada Training Credit would provide Canadians with $250 per year, or up to $5,000 over their lifetime, to apply against training fees at eligible institutions.

Additional federal tools are available to support individuals pursuing education or training. Education can be financed through the Registered Education Savings Plan; the Lifelong Learning Plan; Canada Student Loans and Grants; the Support for Apprentices; and programs targeting specific groups, such as Indigenous students, reservists, athletes, and persons with disabilities. Work-integrated learning is supported through the Student Work Placement Program, which offers wage subsidies to employers who provide work placements to STEM or business students and creates partnerships with post-secondary institutions to recruit students for these placements.[57]

The Canada Job Grant helps to pay for training programs offered by colleges, trade union centres, or other eligible third-party trainers. Trade unions receive funding for skills training through the Union Training and Innovation Program, which supports cost-shared purchases of training equipment and materials. Moreover, certain Indigenous service delivery organizations receive funding through the through the Indigenous Skills and Employment Program to provide skills development, job training, and employment services.

Federal government as an employer

The federal government plays important roles both as employer and regulator. The federal government is one of largest employers in the country. In 2018, there were over 270,000 workers employed in the core public administration and the federal agencies.[58] Types of employment include: indeterminate or permanent positions, term, student positions, seasonal, casual, and on-call employment. The government also relies on a range of workers who are not employees (temporary staffing agency workers, independent contractors or consultants and sub-contractors) to meet its human resource needs.[59]

The federal government regulates workplaces within its jurisdiction. The federally regulated private sector employs about 6% of the workforce. This represents roughly 18,000 employers and 910,000 employees.[60] Federally regulated businesses and industries include interprovincial and international services (such as railways, road and air transport, and shipping services), radio and television broadcasting and cable systems, banks, most federal Crown corporations, as well as private businesses necessary to the operation of a federal Act.[61]

It is noted that the vast majority of employees (85%) in the federally regulated private sector have permanent, full-time jobs, higher than the proportion of other employees in Canada (71%). Approximately 8.7% of workers in the federally regulated private sector earned $15 per hour or less; significantly lower than the national average, an estimated 26% of workers.[62] It is also noted that men comprise 62% of workers in the federal regulated private sector. This is significantly higher than in provincial jurisdictions where men comprise between 52% and 53% of all workers.[63]

Federal government as regulator

The Canada Labour Code (the Code) is the primary legislation that regulates workplaces in the federal jurisdiction. The Code comprises three major parts: Part I (Industrial Relations), Part II (Occupational Health and Safety) and Part III (Labour Standards). Part I governs the collective bargaining process.[64] Occupational health and safety in the federal jurisdiction has been consolidated under Part II of the Code, the purpose of which is to prevent work place related accidents and injury including occupational diseases.[65] Federal labour standards are established under Part III of the Code. Part III sets out minimum standards that federally regulated employers and employees must follow. These standards relate to hours of work, vacation and general holidays, leave, termination, layoff or dismissal, wages, pay and deductions.[66] All other persons work in provincially or territorially regulated industries and have access to their province or territory’s labour standards regime.[67]

The minimum wage is a basic labour standard that sets the lowest wage rate that an employer can pay its employees who are covered by the relevant legislation. For more than 20 years, the federal minimum wage has been pegged in the Code to the minimum wage rate in the province or territory in which the employee is usually employed.[68]

Generally speaking, the Code provisions apply to workers in traditional employment relationships. However, today many workers are engaged in non-standard employment (i.e. independent contractors and subcontractors, temporary agency workers) and may not have access to these protections.[69]

CHAPTER 2: WHAT CAN BE DONE TO MAKE EMPLOYMENT LESS PRECARIOUS?

I think people may be looking for one silver bullet… I would recommend that people think more in terms of using a basket of measures… that touch on different aspects of precarity… I honestly don't see a way of coming up with a single measure that would quantify precisely the number of people in a precarious position.

Vincent Dale[70]

While there was no consensus among the witnesses on how to define precarious employment or even if it was possible to do so,[71] witnesses did agree that greater clarity and coherence is needed.[72] Specifically, witnesses urged the government to identify, measure and organize the major elements related to precarious employment.[73] Several witnesses referenced broad frameworks outlined by the European Union, the ILO and the OECD and recommended adapting them to the Canadian context. These frameworks rely on critical dimensions that can be used to organize the important elements of precarious employment. Using the dimensions of income, security and opportunity to articulate the scope of precarious employment it is possible to organize important elements of precarity and in turn map these elements to policy tools that the government can use to respond.

Start with the problem you are trying to solve

We designed the blueprints of our social safety net and our foundational labour legislation standards in a very different era … most labour legislation regulations and institutions … were put in place in the 1970's and the 1980's, a time when many businesses were large, mainly manufacturing, most workers were male and were the main source of full-time, full-year jobs. Large employers were often protected by tariffs, faced limited competition and union coverage was far higher whereas today there are more small employers, more open competition, more services, and of course more women in the labour force.

Colin Busby[74]

Witnesses spoke to the need to modernize labour regulations and social protection programs to address 21st century economic and workplace realities. It was also strongly suggested that any discussion of the meaning or scope of precarious employment should focus on the problems that we as a society and government are trying to solve.[75]

Low-income

Several witnesses underscored the need to understand precarious employment through the lens of poverty and low income.[76] Looking at the problem this way includes not only workers who are working part-time involuntarily or are scrambling to put together a series of short-term contracts, but also individuals who are working in permanent full‑time low-wage jobs who are unable to make ends meet.

[W]e need to prevent people from bouncing in and out of poverty.

Francis Fong[77]

The Committee also heard that lacking non-wage benefits can increase a worker’s precarity. Paying out of pocket for medications and dental visits can be a further strain on many who are in precarious employment. In addition, the Committee heard that taking unpaid days off due to sickness or to care for a sick child can make it impossible to make ends meet, as well as jeopardize a person’s employment.[78] On a related note, witnesses identified income volatility as an important component of precarious employment.[79] Income volatility is often described as large fluctuations in income from month to month that make it difficult to budget, plan for the future or save.[80]

Identifying low-income as an essential dimension of a precarious employment framework also suggests a ranges of policy tools to address the issue. These tools include income support programs that can support workers with low earnings, including: EI, GIS, and the Working Income Tax Credit (now the Canada Workers Benefit).

However, several witnesses suggested to the Committee that the government explore policy tools that are not strictly tied to employment.[81] Employment-based policy tools like EI, Canada Pension Plan, and registered retirement savings vehicles all come with conditions for qualifying and receiving benefits. Many workers in precarious employment will be ineligible to participate in these programs.

The Committee was told that income security was needed for people while they were in transition, while they were ‘’studying, transitioning between school and employment, retraining, looking for better opportunities, or becoming an entrepreneur, as well as while they are managing a divorce, childbirth, a health condition or anything else life brings.’’[82] It was pointed out that unconditional transfers to individuals, such as Old Age Security and children’s benefits are widely accepted and have been shown to reduce both the incidence and depth of poverty in these age groups.[83] The Committee heard that guaranteed income programs for the working age population could make employment for many low-wage and low-income workers less precarious, although potential concerns with such programs were also raised.[84] Representatives of both business and labour also noted the benefits a pharmacare program could have in the context of precarious workers’ income security.[85]

Lack of security

Imagine going into work day after day and not being able to settle into your work knowing that you must be continuously searching for another job.

Allyson Schmidt[86]

Witnesses described the impact of job insecurity (i.e. temporary and involuntary part-time working arrangements and well as solo self employment) on workers, their families and the economy.[87] Workers in these insecure non-standard working arrangements are often unable to save for retirement or a home purchase. Many with unstable incomes end up ‘’floating their lives on credit and non-banking financial services. The cycle … puts people in financial trouble and puts hard-working Canadians even further behind.’’[88]

Precarious employment is linked to workplace accidents

The Committee learned that Part II of the Code relies on the internal responsibility system. The internal responsibility system is based upon the premise that no one knows a workplace better than the people who work in it. It gives employees and employers a strong role in identifying and resolving health and safety concerns. Worker participation measures such as occupational health and safety committees ensure workers have a voice in health and safety issues. It offers security and protection if they need to speak up because of hazards in their workplaces. However, those with insecure jobs, such as temporary employees, temporary agency employees and independent contractors, are less likely to speak out when they are exposed to hazards.[89]

Professor Katherine Lippel testified that the incentives in workers compensation system encourage firms to outsource hazardous work using temporary agencies. Using temporary agency employees means that experience-rated[90] workers compensation premiums are not adversely affected if there is an accident.[91] Professor Lippel also noted that in triangular employment relationships such as those involving temporary agencies there can be confusion as to which employer is responsible for protecting the workers from hazards including providing essential training and protective clothing. She also noted that self-employed workers are often unprotected by occupation health and safety provisions.[92]

Finally, Professor Lippel called attention to how workers in precarious employment are supported if they are injured on the job or if they develop diseases in the course of employment. She explained that the salary base determines the level of economic support and the level of rehabilitation supports that are offered. As a result, part-time and temporary employees are more likely to receive low levels of compensation and may be systemically undercompensated. Moreover, the right to return to pre-injury employment is often reserved for permanent employees. Thus, according to professor Lippel’s analysis, some workers are doubly penalized, receiving lower benefits and having fewer rights to return to work.[93]

Insecurity can lead to poor health outcomes

Being precariously employed affects physical health, mental health and relationships with family and community.

Allyson Schmidt [94]

Allyson Schmidt also contributed to the Committee’s understanding of the health impacts of insecure employment. She described the ‘’stress of constantly applying for contracts and the stress of never feeling good enough or qualified enough.’’[95] She also emphasized the negative impacts of insecure employment on relationships vital to good mental health, saying ‘’[i]t is a big struggle to engage in the community.’’[96]

Addressing the lack of security as an essential dimension of precarious employment suggests a certain suite of policy tools., the Code being one of the most important. However, the Committee also heard that the government should not craft regulatory solutions before it understands the problem.[97] Monique Moreau of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business also cautioned that the government ‘’cannot regulate the new economy in the same way as they did the old.’’[98]

[T]he government ‘‘cannot regulate the new economy in the same way as they did the old.’’

Witnesses also pointed to the government’s important role as an employer. The government through its own human resources policies can prioritize less precarious working arrangements. It can also ensure that all independent contractors and temporary agency workers have access to full occupational health and safety protections and are included in workers compensation benefits and can restrict or eliminate its use of these arrangements.[99]

Lack of opportunity

Another critical dimension of precarious employment relates to the opportunities a worker has for skills training and career advancement. It is also important to consider whether the worker has other employment opportunities available or because of a combination of age, health status, region and lack of education is stuck in precarious employment.[100]

How do you get out of precarious employment?

It's a multi-million dollar question you're asking and it's quite complex.

Andrew Cardozo[101]

Several witnessed emphasized skills and skills policy, stressing the importance of getting these policies right. Workers need the right kinds of skills as well as access to life-long learning opportunities if they are to make the most of opportunities in an economy where low-skilled jobs will be increasing automated and offshored.[102]

Witnesses encouraged the government to make skills training a priority. Yet, there was also concern that recently proposed measures like the Canada Training Benefit and leave provisions related to training needed to be more precisely defined and well implemented.[103]

The Committee heard that employers may under-invest in training and developing their existing workforces because of the fear of “poaching” or losing trained staff to competitors who are not investing in training. It is easier to hire someone who has been trained elsewhere than risk making the investment upfront.[104]

In addition, it was noted that it is ‘’typically the higher-paid, already more highly educated employees who receive the lion's share of training.’’[105] The people who need it the most are the ones who are least likely to receive training, and they're often the individuals who need basic investments in literacy, numeracy, digital skills and the like.[106]

The Committee was reminded that there are many factors that need to be considered concerning workers’ opportunity to benefit from training as way out of precarious employment. Workers may have family obligations that tie them to a particular region or that prevent them from signing up for training. There may be health challenges. Older workers with lower levels of literacy or numeracy face different challenges learning new skills that could improve their job prospects. Ms. Schmidt brought these issues into focus when she said:

I don't have the ability to move to Toronto or Ottawa or to a bigger centre. I am in a small town in northern Ontario, and this is where I have to live because of the nature of my family… I was told by my [Master’s thesis] supervisor at the time that there was no point in my getting an education because statistically, as a single mother I have more hope of getting out of poverty by getting married than by pursuing an education.[107]

Giving workers voice

Several witnesses spoke about needing to ensure that workers have a voice or more opportunities to exercise their voice in the workplace. Traditionally that has meant being in a union and being able to bargain collectively for better wages and benefits. More recently, however, the concept of worker voice has been expanded to include expressing preferences for work-life balance and flexibility in the way work is performed. It also speaks to being able to bring forward health, wellness and safety concerns.[108]

Chris Roberts of the Canadian Labour Congress noted that unions are trying to organize workers in precarious employment and while they are focussed on collective bargaining coverage and all the benefits that come with that they are also devising new forms of organization and working through public policy advocacy to expand universal social protections like pharmacare.[109]

Seeing lack of opportunity as an important dimension of precarious employment suggests certain policy tools may be appropriate. Notably, investments in training and exploring the Code to support all workers having a greater voice in the the workplace through either collective bargaining or other measures holds promise.[110]

The future of work in the new economy is evolving

It is not all gloom and doom.... There is possibility, potential and opportunity.

Leah Nord[111]

There is a new reality in the world work: ‘’Gone are the days when Canadians go to secondary school then, possibly or not, post-secondary, get a job with at least a single company over a lifetime and then retire at 65 with the income and benefits.’’[112] Changes in technology that began 20 years ago are picking up momentum. Furthermore, there is no point wishing this new reality away: business, government and workers must adapt.

Both the Canadian Chamber of Commerce and the Canadian Federation of Independent Business have done research and surveyed their members on the possibilities posed by the new technology and information driven world of work. It was stressed that having highly skilled workers was essential to take advantage of emerging opportunities.[113]

The greater the expertise and competencies of the worker, the greater flexibility they will have in their work arrangements. In turn, these workers will be able to contribute more to the nimbleness and competitiveness of the organization. Both workers and firms need and want flexibility. We need better data and better understanding of the issues. Leah Nord of the Canadian Chamber of Commerce stressed that ‘’until we know if and where the issues and challenges lie in a gig economy, especially in the federally regulated private sector, we should not be jumping to program solutions.’’[114]

The Committee also heard from the Pearson Centre for Progressive Policy that society should be actively preparing for the future of work. Precarity is an important aspect, but the focus needs to be on opportunities and solutions. In order to do so, we need to be identifying new and future sectors of the economy. There will be important opportunities to advance equality and inclusive workforces and to increase participation from under-represented groups including Indigenous Peoples. Preparing for the future of work means working together with the private sector, labour, different levels of government, educators, families and workers to better understand and identify the range of possibilities.[115]

Not all non-standard workers have poor quality jobs and are precariously employed

The Committee was reminded of many examples of self-employed professionals in high wage occupations such as physicians, dentists, lawyers and accountants; successful business owners; as well as high wage contract workers in the information technology sector. Furthermore, some individuals may also prefer a non-standard form of work for reasons ranging from personal preference, caring for children, or going to school. About three-quarters of part-time workers choose this type of work voluntarily.[116]

43% of small businesses are likely to convert a temporary employee into a permanent one.

Monique Moreau[117]

It was acknowledged that sometimes businesses do use temporary workers because it allows for flexibility in meeting shifting demands. Yet, there are also issues related to finding qualified labour to fill permanent positions. It was also noted that for many small businesses a temporary contract is the first step towards full-time permanent employment and can be accompanied by employer-provided skill training.[118]

About three-quarters of part-time workers choose this type of work voluntarily.

The Committee was cautioned that any attempt to regulate or address non-standard working arrangements needs to recognize the intentions of workers and employers.[119] In addition, regulations need to consider desire the of both employers and workers for flexibility and the red-tape involved with hiring and training. Finally, it was noted that supporting entrepreneurship is vital for the highly automated knowledge-based economy of the future. Government needs to support these self-employed workers so that they can continue to innovate and take advantage to emerging opportunities.[120] It comes back to having the right skills as well as the resiliency, adaptability, and the culture shift in mindset.[121]

CHAPTER 3: FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

In the course of this short study, the Committee heard moving testimony about the hardship experienced by workers in precarious employment. While it is clear that more research and study is required in order to truly understand the phenomenon and develop appropriate responses, the Committee recognizes that there are workers in precarious employment who are struggling right now and need support.

Arrive at an understanding of precarious employment

This comes back to the issue of addressing what the actual problem is or defining what the problems are and what the solutions are.

Leah Nord [122]

The Committee heard that greater clarity is needed in order to define and understand precarious employment. The Committee heard from a number of witnesses who described the need for a precise definition in order to improve the lives of precarious workers. This was coupled with reminders from witnesses that a definition must match its purpose, meaning that definitions in the context of labour regulation, income supports, and the collection of statistics could differ from one another. The Committee also understands that further investigation is required in order to create a definition that will best position the government to support people who are precariously employed. Recognizing this reality, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That Employment and Social Development Canada work with relevant government departments and agencies in consultation with industry, labour, academia, workers with lived experience of precarious employment, and other stakeholders, in order to come to a common understanding of precarious employment, and in so doing, consider the following dimensions and elements: compensation (including wages, benefits, and income volatility), job security (including work arrangements and sectoral changes), working conditions, opportunities for career development, and an individual’s circumstances.

In addition, recognizing that good data is important in the policy development process the Committee recommends further that:

Recommendation 2

Employment and Social Development Canada work together with Statistics Canada to

- develop a data strategy for measuring these elements that includes quantitative, qualitative and longitudinal components; and

- ensure the data strategy incorporates the labour market participation, income security outcomes and skills of vulnerable groups (including women, Indigenous people, visible minorities, youth, recent immigrants, temporary foreign workers, interns, seniors, and people with disabilities).

Address workers living in low-income

The Committee heard that low-income and income volatility are essential elements of precarious employment that need to be addressed. Income support programs have the potential to improve the lives of workers who are struggling in precarious non-standard working arrangements. These programs also can support low-wage workers who are not able to afford basic necessities like medication, dental care and vision care.

The changing nature of work and increasing automation point to the need to explore new types of income supports that do not depend upon someone having a job.

The Committee recognizes recent Budget announcements related to EI, the Working Income Tax Benefit (Canada Workers Benefit) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement that if implemented will increase income security for qualified recipients in precarious employment. Yet, it must also be said that the Employment Insurance program does not work for many in precarious employment situations. Some workers do not have enough hours to qualify. Others who are self-employed find the program, developed in a different era for different purposes, does not address their circumstances. In order to better meet the needs of workers in precarious employment the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 3

That Employment and Social Development Canada review and reform Employment Insurance to better support workers in precarious employment including those in self-employment. To this end, reforms must consider:

- reducing the number of hours worked required to qualify;

- increasing the amount of the benefit for workers with low earnings;

- the rules that apply to and benefits available to self-employed workers;

- the accessibility of skills training and vocational programs delivered through Employment Insurance; and

- international best practices.

In addition, the Committee also heard that income support programs that were tied to employment need further scrutiny. The changing nature of work and increasing automation point to the need to explore new types of income supports that do not depend upon someone having a job. The Committee recognizes that in Budget 2019, the government announced its intention to move forward on a pharmacare program. While pharmacare addresses one aspect of precarity there are other aspects that would benefit from further study. Therefore, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 4

That Employment and Social Development Canada study forms of income support, such as a guaranteed annual income or other transfer programs, that are not tied to employment.

Improve security

As an employer

The federal government as an employer, because of its size and its commitments to equity and representing the rich diversity of Canadian society, is in a unique position to lead by example. The Committee recognizes that there is an important opportunity to model best practices as it relates to reducing precarity in the workplace. This includes improving job security but also security related to health and safety and the security that workers have to assert their rights. Accordingly, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 5

That Employment and Social Development Canada work with other federal government departments and agencies to review human resources practices with a view to:

- reducing reliance on temporary agency workers and solo self-employed;

- improving protections of temporary agency workers and solo-self employed to ensure that they enjoy the same level of occupational health and safety protections and access to workers compensation; and

- reviewing human resources policies and budgeting practices to ensure that they incentivize hiring employees on indeterminate contracts.

As a regulator

The Committee heard that, as regulator, the federal government has an important role to play in addressing precarious employment. Through the Canada Labour Code, the government is in a position to ensure that: the laws governing industrial relations (Part I) recognize the positive impact that worker organization can have in reducing precarity; occupational health and safety protections (Part II) are robust and encourage worker voice and labour standards legislation (Part III) offer both protection and flexibility. The Committee also recognizes the government has convened an Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards for the purpose of reviewing and revising Part III of the Canada Labour Code. While the Committee supports this work, it believes that the review must take into account additional factors to address precarious employment. To this end, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 6

That Employment and Social Development Canada and the expert panel:

- Refine the scope of the review, recognizing that low-wage workers and vulnerable workers (women, youth, seniors, Indigenous workers, recent immigrants, people with disabilities, visible minorities, interns and temporary foreign workers) need to be considered; and

- Explore Parts I and II of the Canada Labour Code as well as other federal programs with a view to making work less precarious.

The Committee also recommends:

Recommendation 7

That Employment and Social Development Canada seek to collaborate with provinces and territories to ensure that workers who may straddle the boundaries of jurisdictions and the employer/employee relationship (especially the self-employed) have access to occupational health and safety protections and workers compensation.

Finally, with respect to the government’s role as a regulator, the Committee heard that more attention needs to be paid to incentives, administrative burden (red tape) and ensuring that workers and employers understand and adhere to laws and regulations. To this end the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 8

That Employment and Social Development Canada make greater investments in staffing the Labour Program inspectorate to:

- promote employer and worker education on rights and responsibilities;

- support employers to meet administrative and reporting requirements; and

- inspect workplaces proactively to ensure compliance with labour standards and occupational health and safety protections.

Help workers get out of precarious employment

The Committee understands that having the ‘’right skills’’ is critical to having opportunities in the labour market. Moreover, the right skill set five years from now may be different from today. In short, what is required is a culture shift that emphasizes life‑long learning and adaptability. To this end the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 9

That Employment and Social Development Canada, business, labour, educators and provincial and territorial governments develop an essential skills agenda for the 21st century workforce. This skills agenda should include:

- the creation of a national skills and competency framework and corresponding assessment tools;

- forecasting future skills needs and measuring existing and forecasted gaps;

- the development of training programs to address these gaps; and

- the development of measures that will support a culture of lifelong learning.

The Committee also recognizes and supports the announcement of the Canada Training Benefit. It is, however, concerned that the benefit be accessible to workers in precarious employment. To this end, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 10

That Employment and Social Development Canada, in the design, roll-out and evaluations of the Canada Training Benefit:

- pay special attention to the circumstances of vulnerable workers, workers in low-wage employment and workers in temporary, involuntary part-time and self-employment working arrangements;

- ensure the Canada Training Benefit is accompanied by appropriate metrics for performance, consulting with employees and employers, and paying close attention to the benefits to our economy over time;

- ensure that employees and employers who access the program will derive benefits from it;

- ensure that as business support their employees who depart for training, the impact on business is minimized;

- ensure that the small business rebate associated with the Canada Training Benefit is sufficient, well-structured, and communicated clearly to employers;

- collaborate with provinces and territories to reach an agreement on corresponding leave provisions; and

- make every effort to ensure take-up of this benefit by these workers.

Bring it all together

Finally, the Committee heard that income supports, laws and regulation and skills development need to all be working together in order make employment less precarious. To this end the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 11

That Employment and Social Development Canada, working with the whole of government, and all orders of government, recognize the impacts to our society posed by the significant rise in precarious employment, and work to achieve the right mix of policies and programs to address the damaging effects of precarious employment on the individual and Canadian families.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this study has been to create the best foundation for developing appropriate and relevant policy.

The nature of work is changing. Yet, the blueprints of our social safety net and our foundational labour legislation were developed in a different time. It was a time when the expectation was that many would spend their life working for a large employer. They would have a pension plan, drug benefits, and perhaps even a dental plan. Moreover, while the federal government has a responsibility to promote skills training and to continuously revise programs to meet the needs of workers, many now believe we are at the beginning of a new technological industrial revolution. This new era will require more than just reforming our skills policies. In order to adapt and embrace the new world of work, the way we approach skills training must change. It is no longer about retraining for a new job. It is about lifelong learning, taking advantage of disruption, and adapting our social safety nets to the work realities of our time.

In this new world of work, it is essential that government, and employers take necessary measures to protect workers from precariousness, the effects of which can be mitigated with efficient policies and social safety nets. The goal of this study has been to create the best foundation for developing appropriate and relevant policy and, in turn, help those living in precarity. In this way, the government will be able to target resources where they are most needed and prepare workers to take advantage of the new opportunities the future will bring.

[1] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 9 April 2019, 1110 (Mr. Terry Sheehan, Member of Parliament Sault Ste. Marie).

[2] Ibid.

[4] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1230 (Mr. Francis Fong, Chief Economist, Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada). HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 4 April 2019, 1110 (Ms. Parisa Mahboubi, C.D. Howe Institute and 1140 Mr. Colin Busby, Research Director, Institute for Research on Public Policy; European Union, OSH Wiki, Precarious work: definitions, workers affected and OSH consequences, accessed 12 April 2019.

[5] Ibid. HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 4 April 2019, 1105 (Ms. Sheila Regehr, Chairperson, Basic Income Canada Network; Mr. Chris Roberts, National Director, Social and Economic Policy Department, Canadian Labour Congress; Parisa Mahboubi). In order for a worker to be protected by the provisions of part II and part III of the Canada Labour Code as an employee, there must be an employer/employee relationship. The employment relationship can be complex, with no quick and easy formulae to use which will provide an instant solution. For more information please see: Employment and Social Development Canada, Determining the Employer/Employee Relationship—IPG-069, 2016.

[7] European Parliament, Policy Department, Precarious Employment in Europe Part 1: Patterns, Trends and Policy Strategy, 2016. European Union, OSH Wiki, Precarious work: definitions, workers affected and OSH consequences, accessed 12 April 2019. Library of Parliament Hillnotes, Precarious Employment in Canada: An Overview, 21 November 2018.

[9] In this instance, “low-paying” refers to Statistics Canada’s benchmark of wages below $15/hour. At the same time, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development defines “low pay" as earning less than two thirds of the median income (OECD, Wage levels). Many observers, including some witnesses, may use more qualitative meanings of low paying and similar terms (low wage, low-income, etc.).

[10] Mitchell, C. et. al. The changing workplaces review: An agenda for workplace rights, 2017.

[11] Tal, Benjamin. On the Quality of Employment in Canada, CIBC Economics, November 2016.

[12] Chen, Wen-Ho et. al., Assessing Job Quality in Canada: a Multi-dimensional approach, Statistics Canada, December 2018. Statistics Canada has evaluated job quality using a framework developed by an agency of the European Union, the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. This framework considers a number of elements of job quality including: compensation, job security, career prospects and work environment.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Statistical agencies often use the longer terms “self-employed, unincorporated, no paid help” (Statistics Canada) or “self employed, own-account, no employees” (International Labour Organization) to describe this situation.

[15] HUMA, Submission (Katherine Lippel) published 10 April 2019. The correlation between non-standard work and occupational health and safety will be explored in greater detail in Chapter 2: What can be done to make employment less precarious?.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid. Also see: Busby, C. et. al. Precarious Positions: Policy Options to Mitigate Risks in Non-standard Employment, C.D. Howe Institute, 2 December 2016.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Mahboubi P., Canada’s vulnerable and precarious workers need more support, C.D. Howe Institute, published in the Globe and Mail Op-Ed, 22 April 2019. HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1110 (Monique Moreau).

[20] OECD, In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, 2015. In the European Union recent estimates of workers on temporary or fixed term contracts are about 7%.

[21] Mahboubi, P., Canada’s vulnerable and precarious workers need more support, C.D. Howe Institute, published in the Globe and Mail Op-Ed, 22 April 2019. Also see: Busby, C. et. al. Precarious Positions: Policy Options to Mitigate Risks in Non-standard Employment, C.D. Howe Institute, 2 December 2016.

[22] For more information, see ILO, Temporary Agency Work.

[23] Ibid.

[24] European Parliament, Policy Department, Precarious Employment in Europe Part 1: Patterns, Trends and Policy Strategy, 2016.

[25] Conference Board of Canada, Canadian Industrial Profile: Employment Services, Spring 2017.

[26] Chen, Wen-Ho et. al., Assessing Job Quality in Canada: a Multi-dimensional approach, Statistics Canada, December 2018.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] The interaction between Employment Insurance (EI) and precarious employment is discussed in greater detail later in Chapter 1.

[30] Statistics Canada, Young people not working, in school or training: What were they doing?, 18 February 2019.

[31] Ibid. See also European Parliament, Policy Department, Precarious Employment in Europe Part 1: Patterns, Trends and Policy Strategy, 2016.

[32] Ibid.

[33] This includes the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program. For more information please see: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Temporary Workers, 2019.

[34] The Committee published a report on the Temporary Foreign Worker Program in September 2016, which describes, in greater detail, how temporary foreign workers can be precariously employed. While significant changes to the program have been made since this report was published, many its findings on the vulnerability of temporary foreign workers remain relevant.

[35] Chen, Wen-Ho et. al., Assessing Job Quality in Canada: a Multi-dimensional approach, Statistics Canada, December 2018.

[36] Noack, Andrea et. al, Precarious Jobs in Ontario: Mapping Dimensions of Labour Market Insecurity by Workers’ Social Location and Context (Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario, 2011), p. 29.

[37] Ibid.

[38] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1130 (Andrew Cardozo and Francis Fong); HUMA, Submission (Pearson Centre for Progressive Policy) published 10 April 2019.

[39] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 9 April 2019, 1235 (Ms. Josée Bégin, Director, Labour Statistics Division, Statistics Canada).

[42] Ibid.

[43] For example, International Labour Organization [ILO], states that “[a]lthough a precarious job can have many faces, it is usually defined by uncertainty as to the duration of employment, multiple possible employers or a disguised or ambiguous employment relationship, a lack of access to social protection and benefits usually associated with employment, low pay, and substantial legal and practical obstacles to joining a trade union and bargaining collectively.” See: ILO, From Precarious Work to Decent Work, 2012.

[44] The European Union identifies four dimensions of precariousness: 1) temporal—low certainty over the continuity of employment; 2) organisational—lack of workers’ individual and collective control over working conditions; 3) economic—insufficient pay and salary progression; and 4) social—lack of legal, collective or customary protection against unfair dismissal, discrimination, and unacceptable working practices and lack of social protections. See European Union, Precarious work: definitions, worker affected and OSH consequences, 2017.

[45] In its recent Employment Outlook 2019: the Future of Work, the OECD states that, “precarious working arrangements are characterized by little pay and limited or no access to social protection, lifelong learning and collective bargaining.”

[46] Fong, F. Navigating Precarious Employment: Who is really at risk, Chartered Professional Accountants Canada, 2018.

[47] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1140 and 1230 (Professor Katherine Lippel, Professor, Faculty of Law, Civil Law Section, University of Ottawa, As an Individual).

[48] For more information on these programs, see Government of Canada, Employment Insurance (EI) and Guaranteed Income Supplement- Overview.

[49] It is also noted that Budget 2019 proposes initial steps to move forward on the implementation of national pharmacare, which would include Canadian Drug Agency and national formulary. If implemented this could be considered a form of income support for low-income workers who are not covered by drug plans and may incur significant out of pocket costs.

[50] Note that Budget 2019 also introduced expansion of parental leave coverage for students and postdoctoral fellows receiving funding from the federal granting councils; and investments in the EI recourse process and the implementation of the EI Parental Sharing Benefit, introduced in Budget 2018. The Committee notes that not all working people contribute to EI, and that many people who have contributed to EI may be unable to claim benefits while unemployed. These issues are explored in greater detail in the the Committee’s report on Employment Insurance and Access to the Program from June 2016.

[51] This announcement is reflected in the the Budget Implementation Act, 2019 as presented for first reading on April 8, 2019.

[52] For further information on program eligibility requirements for regular benefits see EI Regular Benefits—Eligibility. Working While on Claim is an initiative under the EI program that allows claimants to receive part of their EI benefits and all earnings from a job. It was originally introduced for those on regular benefits to encourage them to take up part-time or temporary work until a full-time job is found. In this way, the worker is more likely to remain attached to the labour force and is able to earn some extra income. Recent legislative changes amended the EI Act so that Working While on Claim is now a permanent fixture of the EI program and those receiving sickness and maternity benefits are eligible to participate.

[53] For further information on program eligibility requirements for special benefits for self-employed please see EI Special Benefits for Self-Employed People—Overview.

[54] These changes are reflected in the Budget Implementation Act, 2019 as presented for first reading on April 8, 2019. They potentially address the low-income dimension of precarity for older workers.

[55] This change was proposed in Budget 2018 and included in the Budget Implementation Act, 2018, No. 1, which received Royal Assent on 21 June, 2018. Further information on the Canada Workers Benefit is available at Government of Canada, Canada Workers Benefit (Working Income Tax Benefit before 2019), 2019.

[56] For more information see: Budget 2019.

[57] The Budget 2019 proposes to expand Student Work Placement Program, setting a ten-year target to make a work-integrated learning opportunity available to every young Canadian who wants one.

[58] Government of Canada, Human Resources Statistics, Population of the federal public service, 2018.

[59] Public Services and Procurement Canada, Employment in the Federal Public Service, 2018.

[60] Employment and Social Development Canada, Federally Regulated Businesses and Industries, 2017.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Employment and Social Development, Federal labour standards protections for workers in non-standard work: Issue paper, 2019.

[63] Ibid. See also: Statistics Canada, Federal Jurisdiction Workplace Survey, 2015.

[64] Canada Labour Code, R.S.C., 1985, c. L-2, Part I, Preamble. Recent amendments cover dependent contractors.

[65] Employment and Social Development Canada. Summary of Part II of the Canada Labour Code, 2015.

[66] Employment and Social Development, Federal labour standards protections for workers in non-standard work: Issue paper, 2019.

[67] Employment and Social Development Canada, Federally Regulated Businesses and Industries, 2017.

[68] For more information on the minimum wage in the federal jurisdiction see: Employment and Social Development, Federal minimum wage: Issue paper, 2019.

[69] Employment and Social Development, Federal labour standards protections for workers in non-standard work: Issue paper, 2019.

[70] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 9 April 2019, 1300 (Mr. Vincent Dale, Assistant Director, Labour Statistics Division, Statistics Canada).

[71] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1230 (Professor Katherine Lippel, Professor, Faculty of Law, Civil Law Section, University of Ottawa, As an Individual). HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 9 April 2019, 1220 (Mr. Éric Michaud, Director, Economic Analysis, Economic Policy Directorate, Employment and Social Development Canada).

[72] HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 April 2019, 1235 (Ms. Monique Moreau, Vice-President, National Affairs, Canadian Federation of Independent Business); HUMA, Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 4 April 2019, 1205 (Ms. Leah Nord, Director, Skills and Immigration Policy, Canadian Chamber of Commerce) and 1240 (Mr. Chris Roberts, National Director, Social and Economic Policy Department, Canadian Labour Congress).