HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

ORGAN DONATION IN CANADAINTRODUCTIONOn 7 March 2016, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (“the Committee”) adopted the First Report from the Subcommittee on Agenda and Procedure and agreed: To request a briefing from the Canadian Blood Services on the “Call to Action” report and on the status of Canada’s organ and tissue donation procurement system; and that the Minister of Health be requested to provide a response to the Committee on the findings of the “Call to Action” report and the actions taken to address the recommendations of the report;[1] As part of this study, the Committee held two meetings, which took place on 7 and 9 May 2018, and heard from a range of witnesses, including representatives from Canadian Blood Services, provincial organ donation and procurement organizations, researchers and health care providers and health charities. This report summarizes the testimony and briefs received from these meetings, which focused primarily on organ donation and transplantation in Canada. This report begins with background information on the potential population available to donate organs in Canada and Canada’s system of organ donation and transplantation. It then examines current trends in organ donation and key challenges facing Canada in this area and the role that the federal government can play in improving Canada’s organ donation and transplantation system. UNDERSTANDING THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF ORGAN DONORSTo address organ donation rates in Canada, it is important to first understand the potential population pool available to donate organs.[2] There are three main types of donors. An intended donor is an individual who has indicated a desire to become a donor upon death or when appropriate, during life. A potential donor is an individual that has been identified within a health care facility as being appropriate to pursue as a donor. Finally, an actual donor is an individual from whom at least one organ has been procured, allocated and successfully transplanted. An actual donor may be either deceased or living. A deceased donor is an individual who becomes a donor following death.[3] A deceased donor provides on average four organs for transplantation.[4] In Canada, an individual may become a deceased donor only if their death occurs under specific circumstances, either through brain or cardiac death. Brain death is defined as the total cessation of brain function as manifested by the absence of consciousness, spontaneous movement, absence of spontaneous respiration and all brain stem functions. Brain deaths often occur as the result of a traumatic event such as a motor vehicle accident, a gun-shot wound or a cerebrovascular accident such as a stroke.[5] “In looking at deceased donation, we need to realize that this is an incredibly rare opportunity. The conditions under which someone can become a deceased donor are the result of probably only 1% of the deaths that happen per year in Canada.” Mr. David Hartell, Executive Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program The Committee heard that in addition to donation after brain death, donation after cardio-circulatory death (DCD) has also been adopted over the past 10 years as an option for organ donation in Canada.[6] CDC may occur in individuals under various circumstances, such as after an unsuccessful resuscitation following a cardiac arrest; a cardiac arrest following the withdrawal of treatment in an intensive care unit; or a cardiac arrest after brain death.[7] However, for an individual to be considered a potential donor, the cardiac arrest must occur in a hospital, which is equipped to follow the candidate as a potential organ donor.[8] As individuals may become potential or actual deceased donors only as a result of a brain death or a cardio-circulatory death under very specific circumstances, the Committee heard that only a small number of individuals end up becoming potential or actual donors. As Mr. David Hartell, Executive Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program, explained to the Committee: In looking at deceased donation, we need to realize that this is an incredibly rare opportunity. The conditions under which someone can become a deceased donor are the result of probably only 1% of the deaths that happen per year in Canada. About 270,000 Canadians die per year and to be considered a potential deceased donor, you have to die in a hospital, in an ICU unit, while on a ventilator, and without any chronic complications that would prevent you from being a donor.[9] A living donor is an individual in good health who donates to a recipient.[10] A living donor may provide only a single organ. Organs that can be donated from living donors include a single kidney, a partial liver, a single lung, or a partial intestine or pancreas. OVERVIEW OF CANADA’S ORGAN DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION SYSTEMThe regulation and administration of organ donation and transplantation is a shared responsibility between federal and provincial and territorial governments. An overview of the roles and responsibilities of the different levels of government is provided below. A. Federal Legislation/RegulationIn Canada, the safety of organs and tissues for transplantation is governed federally under the Safety of Human Cells, Tissues and Organs for Transplantation Regulations[11] (Regulations) pursuant to the Food and Drugs Act which standardize the screening and testing of potential donors in Canada.[12] The regulations require that the procuring health care facility undertake the following steps to determine donor suitability:

Exclusionary criteria for donor suitability include health risk factors such as death from unknown causes; affliction with dementia; and infection or high risk of infection, with HIV, viral hepatitis or rabies, as well as other factors.[14] However, sections 40 and 41 of the Regulations do allow for the use of organs from donors who would normally fall under the exclusionary criteria under certain conditions, including informed consent from the recipient.[15] Witnesses explained to the Committee that this means there is not an automatic exclusionary ban on organ donation by men who have sex with men.[16] In discussing how exceptions to the exclusionary criteria in the Regulations would apply in practice, witnesses explained to the Committee that advances in medicine have meant that medical teams are able to mitigate potential health risks to allow organ donation and transplantation to proceed in these exceptional cases: We have come a long way in the last decade in understanding how significant the risks are from various different possible infections an individual may have. Even in the situation of an intravenous drug abuser who may have hepatitis C, we now understand what the risk is to the recipient. The medical team has the ability to come up with the decision and make a recommendation to that individual. The individual, of course, will make the final decision, but we know in that situation, for example, that we can transplant that patient and treat them with very effective anti-hepatitis C drugs afterwards.[17] B. Provincial/Territorial Legislative and Governance Frameworks for Organ DonationProvinces and territories have legislation governing all other aspects of organ and tissue donation. With the exception of Quebec, where organ donation provisions are included in its Civil Code, all provinces and territories have statutes that vary to some degree from an Act proposed in 1990 by the Uniform Law Conference of Canada (ULCC).[18] This proposed uniform Act:

Provinces and territories are also responsible for the administration and delivery of health care services, including organ donation and transplantation.[20] Consequently, each province has established its own organ donation organization and/or specific programs for organ donation and transplantation.[21] The federal government provides financial support to the provinces and territories for the provision of these services under the Canada Health Act.[22] C. Canadian Blood ServicesThe Committee heard that in 2008 federal, provincial and territorial ministers of health asked Canadian Blood Services (CBS) to help strengthen the organ donation and transplantation system across Canada.[23] In particular, the organization was asked to help increase access to transplant opportunities that may cross jurisdictional boundaries to support equitable access to organs across Canada. Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, CBS explained to the Committee that since 2008, his organization has developed a plan and several programs and initiatives to support interprovincial organ donation and transplantation. For example, he highlighted the Kidney Paired Donation Program, which helps match patients with donors across the country and has resulted in 1,000 kidney transplants over the past 10 years.[24] He also explained that CBS has developed the Highly Sensitized Patient program, which is a registry that matches kidney patients whose immune systems are highly sensitized with suitable donors across the country. This program has created more than 575 transplant opportunities that otherwise would not have been available. The Committee heard that these inter-provincial organ sharing programs are implemented in partnership with provincial and territorial organ donation and transplantation programs and are based upon interprovincial organ-sharing agreements.[25] In addition, the Committee heard that the Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation and Canadian Blood Services have developed national leading practice standardized guidelines to support organ donation across Canada, including guidelines for:[26]

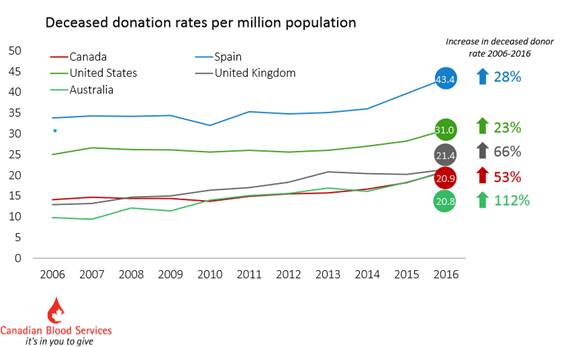

Finally, CBS also undertakes data collection and national performance reporting related to organ donation and transplantation in Canada.[28] Dr. Levy explained that CBS carries out these programs and initiatives through funding it receives from federal, provincial and territorial governments. The organization receives $3.58 million per year from Health Canada to support these efforts.[29] CURRENT TRENDS AND STATISTICS IN ORGAN DONATION IN CANADADr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, explained to the Committee that from 2006 to 2016, there was a 49% increase in the total deceased donor rate in Canada, which is measured as the number of donors per million population.[30] In 2016, the deceased donor rate was 21.0 per population million. Of the 2,835 organ transplant procedures that were performed in Canada in 2016, organs were obtained from 758 deceased donors and 544 living donors.[31] As of 2017, the deceased organ donor rate in Canada was 22.0 per million population.[32] The Committee heard that a significant factor in the increase in Canada’s deceased donor rate has been the development of criteria and programs across the country to allow for donation after cardiac death.[33] In 2016, donations after cardiac death accounted for 23% of total deceased donors per million population, whereas in 2006, they accounted for only 1%.[34] These improvements in Canada’s deceased donor rate mean that the country now ranks among the top 20 countries in the world with respect to deceased donor rates.[35] However, Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services, noted that deceased donor rates in Canada remain half the rate of some of the highest performing countries in the world, such as Spain (see Figure 1).[36] Figure 1. International Deceased Organ Donor Rates Comparison, 2006-2016

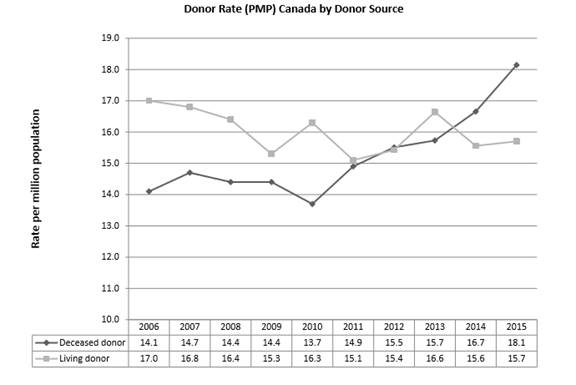

Source: Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. In contrast, the Committee heard that living donor rates per million population in Canada have remained stagnant or declined slightly between 2006 and 2015, from 17.0 per million population in 2006 to 15.7 per million population in 2015 (see Figure 2). However, Dr. Levy noted that despite a lack of improvement in this area, “Our living donation rate, on the other hand, compares quite favourably internationally.”[37] With a rate of 15 per million population, Canada ranked 14th internationally for living donors in 2016.[38] Figure 2. Canadian Organ Donor Rates by Donor Source, 2006-2015

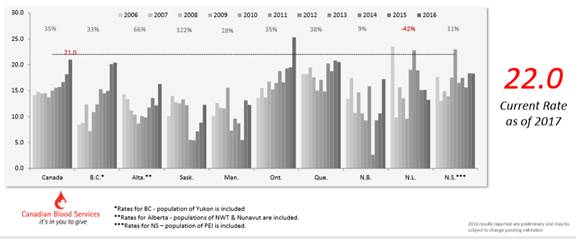

Source: The Kidney Foundation of Canada, “Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health on the Role of the Federal Government in Improving Canada’s Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation System,” 9 May 2018. KEY CHALLENGES FACING ORGAN DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION IN CANADADespite improvements over the past decade in Canada’s deceased organ donor rates, the Committee heard that there are on-going challenges with respect to organ donation and transplantation in Canada that need to be addressed. Witnesses explained to the Committee that donor rates are not meeting current and future patient needs for organ donation; there are significant variations in donor rates and programs across the country; not all opportunities for organ donation and transplantation are being realised; and there are challenges associated with consent to donation and outcomes from transplantations. An overview of these issues is provided in the sections below. A. Organ Donation WaitlistDr. Lori West, Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program explained that despite the increasing number of organ donations taking place in Canada, they are not sufficient to meet current or future patient needs, resulting in the deaths of individuals on organ donation waiting lists.[39] The Committee learned that in 2016, there were 4,492 Canadians on the waitlist for organ donation and 260 Canadians on that list died waiting for a transplant.[40] According to Ms. Elizabeth Myles, National Executive Director, the Kidney Foundation of Canada, 75% of individuals on the organ donation waitlist are waiting for a kidney and the median waiting time for a kidney transplant is four years, ranging from 5.7 years in Manitoba to three years in Nova Scotia.[41] The Committee also heard that the current organ donation waitlist does not reflect the actual need for organs in Canada. According to Ms. Myles, only 16% of the 22,000 Canadians whose kidneys have failed are currently on the transplant waitlist.[42] She further explained that without an organ transplant, the only other treatment available to Canadians with kidney failure is dialysis, which has a lower five-year survival rate than organ transplantation (45% versus 82%) and offers a lower quality of life to patients. According to Ms. Myles, kidney transplants also reduce health care costs: The total annual cost of dialysis ranges from $56,000 to $107,000 per patient. The cost of a transplant is about $66,000 in the first year and about $23,000 in subsequent years. Therefore, the health care system can save up to $84,000 per patient transplanted annually.[43] In its written submission to the Committee, the Canadian National Transplant Research Program explained that organ transplantation is not only a treatment option for individuals facing organ failure but is also “poised to become the preferred treatment for diseases such as type 1 diabetes, kidney disease, cystic fibrosis, heart failure and complex congenital heart disease, lymphoma, myeloma, and leukemia.”[44] B. Variations Across the Country in Organ Donation and Transplantation RatesAccording to Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, though there has been an increase in deceased donor rates in Canada over the past 10 years, increases have varied significantly across the country, ranging from an increase of 112% in Saskatchewan to increases of 9% and 11% in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, respectively (see Figure 3).[45] Figure 3. Deceased organ donor rates per million population (PMP), 2006-2016

Source: Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. The Committee heard that the variation in deceased donor rates across the country are the result of varying capacities and resources across jurisdictions to implement best practices in organ donation.[46] The Committee heard that while some jurisdictions in Canada, such as Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec, are considered leading centres of excellence in organ donation, others vary in terms of the types of programs available: There's no question that performance varies across jurisdictional and even institutional programming. That is something we can collectively put our minds to, I think. The role and scope of activities across jurisdictions with donation programs working with hospitals facilitating the donation process does vary. We see some programs responsible for deceased donation only. We see others include aspects of living donation, transplant services, etc. Some will include tissue donation. Others don't. Some have no deceased donation program at all. Others have no living donation program.[47] “There's no question that performance varies across jurisdictional and even institutional programming. That is something we can collectively put our minds to, I think.” Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services Dr. Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services explained to the Committee that this variation in organ donation programs and services across the country means that it creates inequities in access to organ donation: “I thought it was important to emphasize the inescapable and regrettable fact that it does matter where one lives in this country in terms of probability of being able to be either a donor or a recipient.”[48] It also means that Canada is not realizing its full potential in terms of improving its rates of living and deceased donors. Given the rarity of organ donation, Dr. Levy further articulated that “it behooves us not to miss the opportunity, when we have the opportunity, to use that donation of an organ or set of organs.”[49] “I thought it was important to emphasize the inescapable and regrettable fact that it does matter where one lives in this country in terms of probability of being able to be either a donor or a recipient.” Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services C. Missed Opportunities in Organ Donation and Transplantation“It behooves us not to miss the opportunity, when we have the opportunity, to use that donation of an organ or set of organs.” Dr. Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services The Committee also heard that opportunities for organ donation and transplantation are being missed more generally within health care systems across the country.[50] According to a 2014 report on the deceased organ donor potential in Canada by the Canadian Institute for Health Information, only one of six potential or eligible donors became actual donors based upon a review of hospital records.[51] Witnesses explained there are a variety of factors that could be contributing to converting potential donors into actual donors, such as a lack of accountability for hospitals if they fail to recognize potential donors; potential donors being recognized but not brought forward to the organ procurement organization for a discussion with their families; and challenges associated with obtaining consent from families for organ donation.[52] According to Ms. Amber Appleby, Acting Director, Donation and Transplantation Canada, Canadian Blood Services, there is a need to implement mandatory death audits across Canada to identify what the country’s donor potential is and better understand the factors contributing to missing potential donors.[53] Similarly, the Kidney Foundation of Canada highlighted in its written submission that there is a need for more and better data concerning missed donor opportunities to address this issue. The organization explained that “Current Canadian approaches to measurement and reporting of potential donor identification and referral are fragmented and lack consistency, timeliness and accessibility of information.”[54] D. Consent to DonateThe Committee also heard that there are challenges in obtaining consent for organ donation. Ms. Ronnie Gavsie, President and Chief Executive Officer, Trillium Gift of Life Network, explained to the Committee that though 90% of Canadians say they support organ donation, only 20% have registered as organ donors.[55] She explained there are a variety of factors for this discrepancy, including myths surrounding organ donation. Some people believe that either their age or religious beliefs could prohibit them from becoming organ donors or becoming an organ donor would affect the hospital care they receive. The Committee also heard that procrastination is also a factor in individuals not registering to donate. The Committee heard that these issues could be addressed through greater public education and awareness regarding organ donation coupled with increased opportunities to register as donors.[56] According to Ms. Gavsie, another issue related to consent to donate are circumstances where families overturn their loved ones’ decisions to donate their organs, which occurs between 10% and 15% of the time.[57] She explained that this mainly occurs in situations of cardiac death when the family decides to remove life support, however, the timing of this decision is based upon the family being all together, which does not give the hospital enough time to put the process in place for organ donation. Dr. Lori West, Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program, further explained that this occurs because there is a discrepancy between the legal landscape that requires consent by the individual for organ donation and what actually occurs at the health care delivery level when it comes time to implement an individual’s wishes .[58] The Committee also heard that this issue would not be resolved through the introduction of presumed consent legislation for organ donation, which assumes that individuals have consented to organ donation unless they have expressly indicated otherwise. As Ms. Gavie explained: Certainly, intuitively it would seem to us that it's a silver bullet. However, when we research the matter and go to the other jurisdictions, we find out that it's not, because the family is still—in all of those countries—required to consent, and because of presumed consent they would never have had the discussion. There's no trigger or reason for a family to have ever discussed it, so the families will say they don't know that their relative really read the small print and understood that he was defaulting to yes and they don't think he would have wanted it.[59] E. Transplant OutcomesFinally, the Committee heard that it was also important to improve outcomes from organ transplantation to reduce the need for re-transplantation.[60] Dr. West explained that there are increasing numbers of individuals whose transplanted organs are failing and more research is necessary to understand why this failure is occurring to reduce the need for re-transplantation, which negatively affects both the health of recipients and the organ donor waitlist in Canada.[61] HOW THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT COULD HELP IMPROVE CANADA’S ORGAN DONATION AND TRANSPLANTATION SYSTEMWitnesses appearing before the Committee highlighted ways in which the federal government could address some of these challenges and help strengthen Canada’s organ donation and transplantation system, while recognizing shared jurisdiction in this area. A. Enhancing Canadian Blood Services’ Role as a National Co-ordinating Agency for Organ Donation and TransplantationWitnesses identified the need for a national approach or strategy for organ donation and transplantation to improve consistency and access to organ donation and transplantation across the country.[62] According to Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, CBS, this approach could be achieved by strengthening Canadian Blood Service’s role as a national coordinating agency and providing it with a stable budget.[63] Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta explained that currently the organ and transplantation section of CBS has a very limited budget that is renewed only every three years on application.[64] The Committee heard that a more robustly funded CBS could play a national leadership role that could include developing a national strategy for organ donation with the following elements: promoting the development and implementation of best practices in organ donation across the country; public and professional education and awareness programs; and interprovincial donor sharing programs.[65] The Committee also heard that additional stable funding for CBS would allow it to strengthen and expand existing interprovincial organ sharing programs, such as the Canadian Transplant Registry, which is a web-based tool that allows for the real-time listing of patients in need of organ transplantation and potential organ donors to allow for rapid pairing for organ donation and the monitoring of organ transplants outcomes.[66] While the Canadian Transplant Registry is in place, the Committee heard from witnesses that additional funding is necessary to ensure that all jurisdictions have the information technology infrastructure in place to participate in this program.[67] The Committee also heard that CBS would like to expand its Highly Sensitized Patient Program to include sharing of other types of organs beyond kidneys, such as hearts.[68] B. Public Education and AwarenessThe Committee heard from representatives from both the Government of Ontario’s Trillium Gift for Life and BC Transplant that public education and awareness campaigns are a critical component of their respective programs’ success in improving organ donation rates in each of these provinces .[69] The Committee learned that public education and awareness campaigns are necessary to promote public conversations about organ donation and encourage people to register their decisions to donate (or not) at the end of their lives. In highlighting the impact of public awareness campaigns on improving access to organ donation, Ms. Ronnie Gavsie, President and Chief Executive Officer, Trillium Gift of Life Network, articulated that: Following the tragedy in Humboldt, and the revelation that one of the victims of that tragedy had registered for donation and went on to save six lives, registration for donation skyrocketed right across the country. When Canadians are reminded of the altruistic nature and the life-saving benefit of donation, they respond. They take action. But they were jolted into it.[70] While provinces and territories undertake public awareness and education campaigns on their own, Ms. Gavsie explained that the federal government could support these efforts by developing and implementing a national, sustained, multimedia campaign to support organ donation in Canada.[71] C. Creating Opportunities to Register to Become a Donor“Following the tragedy in Humboldt, and the revelation that one of the victims of that tragedy had registered for donation and went on to save six lives, registration for donation skyrocketed right across the country. When Canadians are reminded of the altruistic nature and the life-saving benefit of donation, they respond. They take action. But they were jolted into it.” Ms. Ronnie Gavsie, President and Chief Executive Officer, Trillium Gift of Life Network The Committee heard that British Columbia has had success promoting organ donation through the creation of different opportunities for residents to register their decisions to become organ donors, such as through provincial service access points where individuals access government programs and services, such as renewing drivers’ licences.[72] Ms. Gavsie explained that the federal government could also create access points for individuals to register to become organ donors. For example, the federal government could promote donor registration when individuals access federal government services available through Service Canada, such as obtaining and renewing passports, registering as voters and filing tax returns.[73] Service Canada could redirect individuals through web-based links to donor registration mechanisms in their respective provinces and territories. Similarly, witnesses expressed support for Private Member’s Bill C-316, An Act to amend the Canada Revenue Agency Act, which would authorize the Canada Revenue Agency to enter into an agreement with a province or a territory regarding the collection and disclosure of information required for establishing or maintaining an organ donor registry in the province or territory.[74] Witnesses further noted that registration for organ donation through federal income taxes should be coupled with the provision of explicit information regarding organ donation to support informed consent in this area.[75] D. Sharing of Best Practices in Organ Donation and TransplantationThe Committee heard that while the delivery of organ donation and transplantation services at the hospital level is a provincial and territorial responsibility, the federal government could play a role in supporting the sharing and implementation of best practices or critical components of high performing organ donation systems, which are in place in some, but not all jurisdictions in Canada.[76] Ms. Gavsie explained that federal funding could be used to develop tools and supports for provincial and territorial health authorities and health care professionals to help them implement best practices.[77]Witnesses explained to the Committee that the federal government could support the provinces and territories in adopting the following best practices, which they identified as being critical factors in promoting a culture of organ donation and transplantation at the health systems level:

E. Research and Data CollectionFinally, the Committee heard that the federal government should support research and data collection to improve health outcomes of organ transplantation. The Committee heard from Dr. Lori West that the Canadian National Transplant Research Program (CNTRP) is a network of investigators, governments, industries, academic organizations, patient partners and funding organizations which conducts research that aims to create a culture of donation; inform best practices for donation; improve grafts available for donation; optimize the immune systems of patients and restore their long-term health.[79] She further explained to the Committee that the CNTRP has received financial support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) ($3 million over three years) to maintain its operations, but it requires additional sustained federal funding to both maintain its world-class research network and realize its objective of eliminating the organ donation waitlist and ensuring that patients must undergo only one organ transplantation in their lives.[80] CNTRP is currently applying for funding through the federal government’s Networks of Centres of Excellence Program. The Committee also heard from the Kidney Foundation of Canada that the federal government could provide support for the development of a national data collection system to monitor outcomes in organ donation to support research and systems improvement.[81] COMMITTEE OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONSThe Committee’s study highlighted the importance of a strong organ donation and transplantation system for improving the quality of life of many Canadians. The Committee heard that organ donation is not only the gift of life for recipients, but also deeply touches the lives of bereaved families of deceased donors. In the words of Ms. Laurie Blackstock, Volunteer, National Office, the Kidney Foundation of Canada: I'm here to emphasize that organ and tissue donation doesn't just help the recipients and their families. It doesn't just reduce the tremendous cost of long-term kidney treatment. It can also be an incredible gift to bereaved families like mine, because when presented gently and ethically, at the right time, when there's little or no hope of a loved one's survival, it is a gift. Knowing that five people's lives probably improved dramatically with Stephen's lungs, kidneys, and corneas doesn't change his death and the intensity of our grief, but it gives us moments of relief. Stephen lives on through those five people.[82] “I'm here to emphasize that organ and tissue donation doesn't just help the recipients and their families. It doesn't just reduce the tremendous cost of long-term kidney treatment. It can also be an incredible gift to bereaved families like mine, because when presented gently and ethically, at the right time, when there's little or no hope of a loved one's survival, it is a gift.” Ms. Laurie Blackstock, Volunteer, National Office, the Kidney Foundation of Canada While the Committee heard that there had been significant improvement in organ donor rates over the past 10 years, witnesses explained that there is more work to be done to realize Canada’s potential in organ donation. They explained that Canada’s organ donation system could be strengthened by supporting the adoption of best practices in organ donation across all jurisdictions in Canada; providing greater public education and awareness to promote conversations among family members regarding organ donation; offering more opportunities for Canadians to register their decisions regarding organ donation; and providing sustained funding for research and data collection to ensure that organ transplantation results in improved health outcomes for Canadians. However, the Committee heard that these things could not be achieved without leadership from the federal, provincial and territorial governments and a stronger role for CBS in the coordination of organ donation across the country. These recommendations are also in line with the federal Minister of Health’s mandate to “facilitate collaboration on an organ and tissues donation and transplantation system that gives Canadians timely and effective access to care.”[83] The Committee therefore recommends: Recommendation 1 That the Government of Canada provide Canadian Blood Services with sustained funding to: a. strengthen and expand upon existing interprovincial organ donation and transplantation sharing programs; b. develop a sustained national multimedia public education and awareness campaign to promote organ donation; and c. promote the adoption of best practices in organ donation and transplantation across the country. Recommendation 2 That the Minister of Health establish a working group with provincial and territorial ministers of health to examine best practices in organ donation legislation across the country, such as the adoption of mandatory referral of any potential organ donor; and identify any barriers to the implementation of these best practices. Recommendation 3 That the Government of Canada consider the feasibility of a presumed consent system for organ donation. Recommendation 4 That the Government of Canada identify and create opportunities for Canadians to register as organ donors through access points for federal programs and services in collaboration with provincial and territorial organ donation programs. Recommendation 5 That the Government of Canada provide information and education to Canadians regarding organ donation as part of its efforts to promote organ donation registration through federal programs and service access points. Recommendation 6 That the Government of Canada continue to provide funding for organ donation and transplantation research through its Networks of Centres of Excellence Program. Recommendation 7 That the Canadian Institute for Health Information and Canadian Blood Services work together to develop a national data collection system to monitor outcomes in organ donation to support research and systems improvement. [1] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Health (HESA), Minutes of Proceedings, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 March 2016. [2] Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [3] Ibid. [4] HESA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 May 2018, 1610 (Ms. Elizabeth Myles, National Executive Director, the Kidney Foundation of Canada). [5] Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [6] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1605 (Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta). [7] Ibid. [8] Ibid. [9] HESA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 May 2018, 1650 (Mr. David Hartell, Executive Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program). [10] Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [12] Food and Drugs Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. F-27. [13] Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [14]. Ibid. [15] Cited in: Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [17] Ibid. [18] Uniform Law Conference of Canada [ULCC], Uniform Human Tissue Donation Act (1990), 1990. [19] It should be noted that while the prohibition on the buying and selling of human organs and tissues would exclude reproductive material, Canada’s Assisted Human Reproduction Act, S.C. 2004, c. 2, specifically prohibits the commercialization of ova, sperm and embryos. [20] Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [21] Ibid. [22] Ibid. [23] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1540 (Dr. Isra Levy, Vice-President, Medical Affairs and Innovation, Canadian Blood Services). [25] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1630 (Ms. Amber Appleby, Acting Director, Donation and Transplantation, Canadian Blood Services) [26] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1530 (Mr. Edward Ferre, Provincial Operations Director, BC Transplant). [27] Ibid. [29] Ibid. [30] Please note that deceased donor rate and deceased donation rate are interchangeable terms that were both used by witnesses throughout the testimony. Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [31] Canadian National Transplant Research Program, “One Transplant for Life: Transplantation saves lives-Be a part of something big,” written submission, 9 May 2018. [32] Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [34] Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [37] Ibid. [38] Sonya Norris, Organ Donation and Transplantation in Canada, Publication no. 2018-13-E, Parliamentary Information and Research Service, Library of Parliament, Ottawa, 14 February 2018. [39] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1550 (Dr. Lori West, Director, Canadian National Transplant Research Program). [40] Canadian National Transplant Research Program, “One Transplant for Life: Transplantation saves lives-Be a part of something big,” written submission, 9 May 2018. [42] Ibid. [43] Ibid. [44] Canadian National Transplant Research Program, “One Transplant for Life: Transplantation saves lives-Be a part of something big,” written submission, 9 May 2018. [45] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1605 (Kneteman) and Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [46] Ibid. [48] Ibid. [49] Ibid. [51] The Kidney Foundation of Canada, “Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health on the Role of the Federal Government in Improving Canada’s Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation System,” 9 May 2018. [53] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1640 (Ms. Amber Appleby, Acting Director, Donation and Transplantation Canada, Canadian Blood Services). [54] The Kidney Foundation of Canada, “Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health on the Role of the Federal Government in Improving Canada’s Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation System,” 9 May 2018, p. 3. [55] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1600 (Ms. Ronnie Gavsie, President and Chief Executive Officer, Trillium Gift of Life Network). [56] Ibid. [61] Ibid. [63] Canadian Blood Services, “Summary of Canadian Blood Services Recommendations to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health,” written submission, 27 July 2018. [65] Canadian Blood Services, “Summary of Canadian Blood Services Recommendations to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health,” written submission, 27 July 2018 and HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1610 (Myles). [67] Ibid. [69] HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1530 (Ms. Leanne Appleton, Provincial Executive Director and Mr. Edward Ferre, BC Transplant) and 1550 (Gavsie). [71] Ibid. [78] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1610 (Kneteman) and HESA, Evidence, 7 May 2018, 1530 (Ferre) and Dr. Norman Kneteman, Professor and Director, Division of Transplant Surgery, University of Alberta, “Brief to the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Health: the Role of the Federal Government in improving access to Organ Donation,” 9 May 2018. [79] Canadian National Transplant Research Program, “One Transplant for Life: Transplantation saves lives-Be a part of something big,” written submission, 9 May 2018. [81] The Kidney Foundation of Canada, “Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health on the Role of the Federal Government in Improving Canada’s Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation System,” 9 May 2018, p. 3. [82] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1610 (Ms. Laurie Blackstock, Volunteer, National Office, the Kidney Foundation of Canada). [83] Prime Minister of Canada, Minister of Health Mandate Letter, 4 October 2017. |