HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

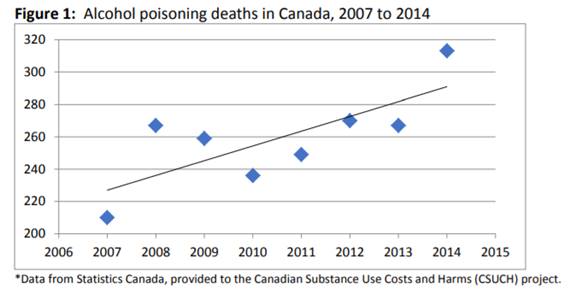

INTRODUCTIONOver the past few years, an increasing number of beverages with high alcohol and sugar content sold in single-serving containers have been making their way into the Canadian market, raising the concerns of many public health experts across the country. On 1 March 2018, Athéna Gervais, a 14-year-old girl, was found in a stream behind her high school in Laval, Quebec after having reportedly consumed a 568 mL can of a beverage containing 11.9% of alcohol or the equivalent of four standard drinks in one serving.[1] The death of Athéna Gervais further raised concerns about potential dangers posed by these drinks. The high sugar content and flavouring ingredients in these beverages mask their strong alcohol content, while their single-serving containers encourage their rapid consumption. The rapid consumption of beverages with a high alcoholic content can lead to acute alcohol poisoning and even death.[2] Alarmed by the tragic of death of Ms. Gervais, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (“the Committee”) adopted the following motion on 19 March 2018: That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the Committee undertake an emergency study of no fewer than three (3) meetings in order to develop recommendations on actions that the federal government can take, in partnership with the provinces and territories, to better regulate pre-mixed drinks with high alcohol, caffeine, and sugar content; that the Committee report its findings and recommendations to the House no later than June 2018; and that, pursuant to Standing Order 109, the Committee request that the Government table a comprehensive response to the report. [3] The Committee subsequently agreed to hold two three-hour meetings to fulfil the terms of the motion. Over the course of two meetings held on 30 April and 9 May 2018, the Committee heard from Health Canada officials, public health experts, physicians, toxicology experts and industry representatives. This report summarizes the testimony and recommendations provided by these witnesses. It begins with an overview of the regulation of alcoholic beverages in Canada, including the different roles and responsibilities of federal, provincial and territorial governments in this area. It then provides an overview of highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages and the health and safety risks that they pose to Canadians and particularly youth. Finally, the report outlines what steps have been taken to date to address the risks posed by these beverages and identifies additional actions that can be taken to improve the regulation of alcoholic beverages with high alcohol and sugar content. OVERVIEW OF THE REGULATION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES IN CANADAIn her appearance before the Committee, Ms. Karen McIntyre, Director General, Food Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch, Health Canada explained that the regulation of alcoholic beverages is a shared responsibility between federal and provincial and territorial governments.[4] 1. Federal Roles and Responsibilitiesa. The Food and Drugs ActAt the federal level, alcoholic beverages are regulated as a food under the Food and Drugs Act[5] and the Food and Drug Regulations (the Regulations).[6] While alcoholic beverages do not need a premarket assessment to be approved for sale by Health Canada, they must meet the standards of production for different categories of alcohol, such as beer, wine, cider, whisky, rum, gin and other spirits, outlined in the Regulations.[7] The Regulations outline permissible ingredients for these products and methods of manufacture. Ms. McIntyre further specified that under the Regulations, flavouring ingredients in which caffeine is naturally present, such as coffee, chocolate and guarana, are permissible as the amount of caffeine they contribute to alcoholic beverages is very low in comparison to a serving of coffee (5 mg versus 180 mg).[8] However, Ms. McIntyre further explained that that the addition of non-naturally occurring caffeine to alcoholic beverages is prohibited under the Regulations. For example, caffeinated energy drinks sold in Canada are prohibited from containing any alcohol, and must display a warning about not mixing these products with alcohol. Finally, the Committee heard that alcoholic beverages are subject to certain labelling requirements under the Regulations, including the common name of the product, quality and alcohol by volume.[9] However, these beverages are exempt from the nutrition labelling requirements for other foods under the Act.[10] Alcoholic beverages are also subject to the general prohibitions against the deceptive marketing of foods in the Food and Drugs Act.[11] b. Alcoholic Beverage MarketingThe federal government is also responsible for regulating radio and television advertising for alcoholic beverages under the Radio Regulations and the Television Broadcasting Regulations under the Broadcasting Act.[12] However, Ms. McIntyre explained that: Alcohol beverage marketing in Canada is largely self-regulated and is primarily governed by the code for broadcast advertising of alcohol advertising of alcoholic beverages set by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, the CRTC. The code imposes content restrictions on alcohol broadcasting advertising, including restrictions on advertising to youth and on the promotion of alcohol consumption. Compliance with the CRTC advertising rules is under the purview of Advertising Standards Canada. However, the CRTC code is voluntary and does not have the force of law.[13] c. TaxationIn his appearance before the Committee, Dr. Tim Stockwell, Director, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria explained that the federal government also plays a role in the price of alcoholic beverages through its imposition of excise taxes on these products.[14] Dr. Stockwell explained that excise taxes are applied first to the wholesale price of alcohol and therefore have an impact on the final retail price of alcohol by influencing price mark-ups and sales taxes, which are applied afterwards.[15] The excise duties that the federal government levies on spirits and wines are set out in Schedule 4 and Schedule 6 of the Excise Act, 2001.[16] The excise duty rate for these products depends upon the percentage of alcohol by volume found in the wine or spirit. Excise duty rates levied on beer and/or malt-based beverages are outlined in the schedule to the Excise Act.[17] The excise duty rate for beer is based upon the percentage of alcohol by volume and the amount of beer produced by the brewer. 2. Provincial and Territorial Roles and ResponsibilitiesThe Committee heard that provinces and territories are responsible for enacting laws and regulations regarding the sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages within their jurisdictions.[18] Each province and territory has a liquor board or commission that is responsible for the control and distribution of alcohol within the jurisdiction. According to Ms. McIntyre, provinces and territories are also able to set out additional health and safety labelling regulations related to alcoholic beverages, as well as control access to these products through pricing, licensing of sale outlets, hours of operation and setting minimum drinking ages. OVERVIEW OF HIGHLY SWEETENED PRE-MIXED ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGESThe Committee heard that there is an increasing prevalence of highly sweetened single-serving alcoholic beverages on the Canadian market. The alcohol content of these beverages, which are sold in large volume single-serving containers, ranges between 7% and 12%. These drinks are also aggressively marketed towards youth.[19] At the higher end of the alcohol content range, the amount of alcohol in these beverages can be equivalent to four standard alcoholic drinks. Under the Canada’s Low Risk Drinking Guidelines, a standard drink of alcohol is defined as 17.05 millilitres or 13.45 grams of pure alcohol per drink.[20] The Committee heard that the highly sweetened alcoholic beverage market is constantly changing with new products, flavours and levels of alcohol content being produced, with a trend towards the production of beverages with higher alcohol content.[21] According to Dr. Réal Morin, Vice-President of Scientific Affairs, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, the sale of these types of beverages with the highest alcohol content (minimum of 11% alcohol content) increased by 319% in Quebec between 2016 and 2017.[22] The Committee heard that these beverages are produced through the fermentation of cereal grains, which are then treated through additional processes to obtain a product that mimics the effects of distillation to obtain a higher alcohol malt-based product.[23] Flavours and sugars are then added to create the final product. These products are therefore either classified as a “flavoured malt beverage” in Canada or a “beer blend” in Quebec.[24] Some examples of these products include Four Loko, produced by Blue Spike Beverages, which contains 11.9% alcohol content and 52 g of sugar (or the equivalent of 13 teaspoons) in a 694 mL can.[25] Another example is a beverage called FCKDUP, which is no longer on the market. It contained 11.9% alcohol in a 568 mL can, approximately 11% sugar content and 5 mg of caffeine from the flavouring agent guarana.[26] FCKDUP was produced by the Geloso Group and was removed by the company from the market in March 2018 after the death of Ms. Athéna Gervais. “A young person makes a financial calculation and looks for ways to get intoxicated at the lowest possible cost. When he finds two cans for $7, when the advertising for the product is misleading, and he can swallow it quickly, which he cannot do with other types of alcohol without rapidly feeling nauseous, we have a perfect recipe for a call to poison control and a visit to the emergency room.” Dr. Réal Morin, Vice-President of Scientific Affairs, Institut national de santé publique du Québec Ms. Catherine Paradis, Senior Research and Policy Analyst, Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA), explained to the Committee that because these products are considered malt-based beverages, rather than spirits, their sale is regulated like beer in provinces and territories, making them both cheap and widely available despite their high alcohol content.[27] As malt-based beverages, they are not restricted to being sold in government or privately run liquor stores, but rather can be sold in convenience stores, grocery stores or beer store locations making them more widely available. In addition, she explained that as malt-based beverages, these products benefit from the lower federal excise tax rates that are applied to beer in comparison to other alcoholic products such as spirits. Malt-based beverages may also benefit from a lower minimum price in provinces and territories that have set minimum prices for alcoholic beverages. Consequently, these products can be sold at deeply discounted rates. According to witnesses, these products can be bought for less than $5.00 per container, which amounts to approximately 74 cents per standard serving, which is far below the recommended price for a standard serving of alcohol of $1.71, a price established by a working group as part of the development of the CCSA’s National Strategy for Alcohol.[28] The Committee heard that the relatively low price of these beverages, coupled with their high alcohol and sugar content encourages their consumption, particularly among youth: A young person makes a financial calculation and looks for ways to get intoxicated at the lowest possible cost. When he finds two cans for $7, when the advertising for the product is misleading, and he can swallow it quickly, which he cannot do with other types of alcohol without rapidly feeling nauseous, we have a perfect recipe for a call to poison control and a visit to the emergency room.[29] Finally, witnesses explained to the Committee that these products are also aggressively marketed to youth, particularly young girls and women, through their packaging, brand naming and social media marketing and Internet marketing strategies. Mr. Hubert Sacy, Director General, Éduc’alcool explained these beverages are sold in brightly coloured packaging and lettering that clearly targets youth, “You need only look at one of these cans to realize that the product isn’t intended for seniors.”[30] Dr. Tim Stockwell, Director, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, and Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Victoria, further pointed out that these products have names that also promote the over-consumption of alcohol, such as “Monster Rehab,” “Four Loko” and “Delirium Tremens.”[31] Ms. Lucie Granger, Director General, Association pour la santé publique du Québec, explained that the industry also uses its inclusion of caffeinated ingredients such as guarana for strategic marketing purposes to promote the over consumption of alcohol: The makers of FCKDUP add on their website: “Combining guaranas with 11.9% grape nectar is like boosting your sports car with nitrous. If you want to go from zero to party in a few gulps, drink the purple.” It uses a formidably effective marketing style that appeals to young people by selling them a lifestyle. It promotes alcohol abuse and that is extremely dangerous.[32] Dr. Réal Morin, Vice-President of Scientific Affairs, Institut national de santé publique du Québec, explained that producers of these beverages are also using social media to market these products directly to youth, through the use of videos and interactive games that portray rappers, disc-jockeys, and childlike characters promoting the consumption of alcohol in direct violation of the CRTC Code for broadcast advertising of alcoholic beverages.[33] Finally, the Committee heard that these marketing strategies are targeted to young women in particular, as they are more likely to prefer sweetened types of alcoholic beverages over the more bitter taste of beer.[34] HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH HIGHLY SWEETENED PRE-MIXED ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES“The makers of FCKDUP add on their website: “Combining guaranas with 11.9% grape nectar is like boosting your sports car with nitrous. If you want to go from zero to party in a few gulps, drink the purple.” It uses a formidably effective marketing style that appeals to young people by selling them a lifestyle. It promotes alcohol abuse and that is extremely dangerous.” Ms. Lucie Granger, Director General, Association pour la santé publique du Québec Witnesses explained to the Committee that the main health risk associated with highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages is their high alcohol content. Mr. Jan Westcott, President and Chief Executive Officer, Spirits Canada, explained that the alcohol content in a single-serving container of one of these beverages exceeds the recommended daily limit under Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines of no more than two standard drinks for women and three for men.[35] Ms. Lucie Granger, Director General, Association pour la santé publique du Québec, explained that youth are even more vulnerable to the effects of alcohol and its physically damaging effects.[36] As youth have lower body weights than adults, their blood alcohol levels rise more quickly and they do not produce a sufficient quantity of enzymes to metabolize the alcohol fully. Consequently, consumption of one of these beverages places youth over the blood alcohol limit, while the consumption of two of these beverages places them at high risk for alcohol poisoning. While the high sugar content of these beverages is not recommended from a health standpoint, witnesses explained that the main risk posed by these beverages is that the sugar masks their high alcohol content, which encourages rapid and over consumption and increases the risk of alcohol poisoning.[37] Witnesses also explained that caffeinated flavourings such as guarana also play a similar role in masking the high alcohol content of these beverages.[38] However, witnesses also pointed out that there are significant risks associated with the mixing of caffeine and alcohol, as caffeine masks the true degree of impairment from alcohol and encourages people to stay awake and drink alcohol for longer periods of time. Dr. Maude St‑Onge, Medical Director, Centre antipoison du Québec, explained that a combination of caffeine and alcohol poisoning can result in cardiac arrhythmia, as well as other complications.[39] She further noted that in Quebec there were 96 cases of caffeine poisoning from caffeinated energy drinks alone in 2017.[40] Dr. Morin explained to the Committee that these beverages are appearing on the market at a time when rates of acute alcohol poisoning are increasing among young people between 12 and 24 years of age.[41] In Quebec, 2,332 individuals in this age group were admitted to hospital for acute alcohol poisoning between 1 January and 26 November 2017, or the equivalent of 214 cases per month, 49 cases per week, or seven cases per day.[42] Furthermore, one quarter of the individuals admitted to an emergency department were triaged at a high priority level, indicating their lives were at risk. Though the data is insufficient to tie these cases of acute alcohol poisoning to these drinks in particular, the Committee heard that their presence on the market encourages these worrying health trends.[43] These trends are not limited to Quebec. Dr. Tim Stockwell explained that deaths from alcohol poisoning in Canada have increased by 37% over the past 10 years from 210 in 2007 to 313 in 2014 (see figure 1).[44] Ms. Catherine Paradis also indicated that studies on these products in the United States have shown that their availability was “associated with various legal problems, including assault, mischief, uncivil conduct, drinking and driving and underage drinking.”[45]

Source: Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director and Adam Sherk, Doctoral Candidate, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, “Inquiry into high alcohol, high sugar pre-mixed alcoholic beverages,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. STEPS TAKEN TO ADDRESS THE HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH HIGHLY SWEETENED PRE-MIXED ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGESThe Committee heard that both the Government of Canada and the Government of Quebec have already taken steps to address the health and safety risks posed by highly sweetened alcoholic beverages. An overview of these measures is provided below. A. Health CanadaAccording to Ms. Karen McIntyre, Director General, Food Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch, Department of Health, Health Canada issued a notice of intent on 19 March 2018 outlining a regulatory proposal to amend the Food and Drugs Act and the Regulations to restrict the amount of alcohol in these types of products.[46] She explained that the notice of intent seeks feedback from stakeholders on the following two issues. First, the department wants feedback on the mechanism used to restrict the amount of alcohol in the product, which could be achieved by limiting the size of the container or by limiting the percentage of alcohol in a single-serving container. Second, the department would like feedback on the “sweetness threshold” in a beverage that would trigger restrictions on the alcohol content. She noted that the department’s proposals are not intended to capture liqueurs, dessert wines and other sweetened alcoholic beverages that are sold in resealable containers. The department is also seeking input from stakeholders on advertising, marketing and labelling to help reduce the risks of these products. In addition, the department is meeting with its provincial and territorial counterparts to determine possible measures to address the problem. Ms. McIntyre explained that the consultations were to close on 8 May 2018 and regulations would be introduced in the fall of 2018. Finally, the department is also trying to raise awareness regarding the risks of these beverages by providing information to parents and their children on Health Canada’s website and through their use of social media. B. The Government of QuebecThe written brief submitted to the Committee by the Association pour la santé publique du Québec outlined the actions taken to date by the Government of Quebec to address the health and safety risks posed by highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages.[47] In October 2017, the Régie des alcools, des courses et des jeux du Québec (RACJQ) analyzed the content of the beverages produced by Blue Spike Beverages and found that they had not been produced through the fermentation of malt but rather by the direct addition of ethanol. In a letter dated 17 November 2018, the RACJQ demanded that four products produced by Blue Spike Beverages be removed from the market by 20 December 2017, including Baron, Four Loko, Mojo and Seagram. On 26 October 2017, the Quebec National Assembly instructed the National Public Health Director to examine cases of alcohol poisoning following consumption of beverages with high sugar and alcohol content, especially among young people. The Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ) reported its findings and recommendations to the Quebec National Assembly in the winter of 2018. After the death of Athéna Gervais on 1 March 2018, the Government of Quebec announced that it intends to ban the sale of mixed malt-based beverages with more than 7% alcohol content in grocery stores and dépanneurs in Quebec through amendments to Bill 170, An Act to modernize the legal regime applicable to liquor permits and to amend various other legislative provisions with regards to alcoholic beverages, currently before the Quebec National Assembly.[48] MOVING FORWARD: HOW TO ADDRESS THE HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH HIGHLY SWEETENED PRE-MIXED ALCOHOLIC DRINKSWhile witnesses were in favour of banning highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, they also recognized that better regulation of these products would also address their health and safety risks as well as prevent new and similar products from entering the market in the future. They therefore provided the Committee with recommendations on how to restrict the alcohol, sugar and caffeine content of these beverages; improve labelling of alcoholic beverages; place additional restrictions on the branding and marketing of alcoholic beverages; and address tax and pricing incentives for these products. Witnesses also identified ways to improve surveillance of these products and address broader issues surrounding the rise of cases of acute alcohol poisoning among youth in Canada. An overview of these recommendations is provided below. A. Restrictions on Alcohol, Sugar and Caffeine ContentWitnesses were in agreement that the alcohol content in these beverages should be restricted to 13.5 g of alcohol or 17.05 milliliters, the content equivalent of one standard serving of alcohol in Canada.[49] At a maximum, the alcohol content should be restricted to 1.5 standard servings of alcohol in Canada.[50] Mr. Luke Harford, President, Beer Canada explained that restricting the alcohol content to a standard serving of alcohol would allow for a different range of sizes of cans.[51] In addition, placing restrictions on the alcohol content based upon the source of alcohol (grain or fruit based) would “restrict innovation among responsible manufacturers while being easily circumvented by those that are not.”[52] In terms of sugar content, Ms. Catherine Paradis, recommended that the sweetness threshold of these products should be set at 5% by volume under the Food and Drug Regulations, which would place them in the category of spirits rather than malt-based beverages.[53] This restriction would mean that, with the exception of Alberta, these products would have to be sold in government-run liquor stores rather than grocery stores or corner stores, effectively limiting their physical availability to youth. This proposal would also exempt all beer as its sugar content is 4%. This proposal also has implications for the taxation and pricing of these products, which will be discussed in subsequent sections of the report. Finally, witnesses were also in agreement that restrictions be placed on the caffeine content of these products. Dr. Maude St-Onge, Medical Director, Centre antipoison du Québec, stated that: I would also add that natural caffeine products such as guarana should be considered the same as artificial, synthetic caffeine. From a toxicological perspective, it’s the exact same thing. It should be considered the same.[54] Dr. Martin Laliberté, Emergency Physician and Toxicologist, McGill University Health Centre further reiterated that: “It should be reminded that all plant extracts cannot be assumed to be safe just because they are natural.”[55] Consequently, witnesses recommended that the caffeine content in these beverages be restricted to 30 mg per standard serving, which is a voluntary standard that has already been established by the Canadian Association of Liquor Jurisdictions.[56] B. Labelling and PackagingThe Committee heard that for the sake of their health and safety, “Canadians have the right to know what they are eating and drinking. While virtually all food and beverages must label calories and ingredients, alcoholic products are exempt from these requirements.”[57] Mr. Jan Westcott, President and Chief Executive Officer, Spirits Canada, explained that this was the case historically because of the transformation that ingredients undergo through the fermentation and distilling processes.[58] However, the Committee heard that there is an urgent need to review the labelling of alcoholic beverages to help consumers estimate their alcohol intake and be aware of the nutrient value of these beverages. Some witnesses therefore recommended that the labels of alcohol beverages include information on:

“Canadians have the right to know what they are eating and drinking. While virtually all food and beverages must label calories and ingredients, alcoholic products are exempt from these requirements.” Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director and Adam Sherk, Doctoral Candidate, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria With respect to the labelling and packaging of highly sweetened alcoholic beverages in particular, Mr. Hubert Sacy, Director General, Éduc’alcool recommended that the lettering, packaging and labelling need to be clearly designed to target adult consumers.[60] C. Marketing and BrandingWitnesses raised several issues that they believed need to be addressed with respect to the marketing of highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages. First, the Committee heard that though adherence to the CRTC’s Code for broadcast advertising of alcoholic beverages is voluntary, it has been adopted by most provinces and territories in their regulations governing the advertising of alcoholic beverages.[61] However, Mr. Jan Westcott, President and Chief Executive Officer, Spirits Canada, explained that the provincial regulator in Quebec “chose not to enforce the relevant sections of the liquor advertising regulations that prohibit advertising that induces a person to consume alcoholic beverages in an irresponsible manner.”[62] Second, the Committee heard that it is necessary to update the CRTC Code for broadcast advertising of alcoholic beverages to apply to advertising of alcohol on social media, as producers of highly sweetened alcoholic beverages are using social media to target youth.[63] The Committee heard that these issues could possibly be addressed through updating the CRTC code, amending the Food and Drugs Act in relation to the marketing of alcoholic beverages, and/or taking a broader legislative approach to alcohol regulation, similar to that which is currently in place for tobacco.[64] With respect to the branding of highly sweetened alcoholic beverages, the Committee heard that the branding or naming of products that make reference to product strength, excessive consumption or make light of alcohol dependence should be prohibited.[65] Mr. Wescott also explained that there are also alcoholic beverages on the Canadian market that use the same brand names and imagery as caffeinated energy drinks promoting the mixing of alcohol and caffeine, despite the fact that alcoholic energy drinks are prohibited in Canada.[66] He therefore recommended that Health Canada prohibit the use of the brand name of an authorized caffeinated energy drink for any alcoholic beverage. Similarly, as noted above, Ms. Granger indicated that producers of highly sweetened alcoholic beverages containing ingredients that have naturally occurring caffeine promote these products on the basis of their caffeine content. D. Pricing and TaxationWitnesses explained to the Committee that studies conducted in other jurisdictions have shown that the primary appeal of highly sweetened pre-mixed alcohol beverages to youth is their low price point. Ms. Paradis explained that by reclassifying these beverages as spirits through a 5% sweetness threshold would subject them to the higher federal excise taxes on spirits, making them less affordable to youth.[67] For example, if a can of FCKDUP had been classified as a spirit, it would have been subject to an excise tax of 82 cents, rather than 18 cents when classified as a malt-based beverage. She explained that when Australia placed these beverages in a higher tax category, there was a 28% drop in sales of these products. Similarly, Dr. Tim Stockwell recommended that federal excise taxes be applied at a fixed rate of 25 cents per standard alcoholic drink, rather than by type of alcohol, to encourage the consumption of lower alcohol content beverages.[68] Finally, witnesses also recommended establishing a common national minimum price for alcohol per standard serving to discourage the high-risk consumption of alcohol.[69] Though the pricing of alcohol is an area of provincial jurisdiction, the Committee heard that the federal government could work with the provinces and territories to establish a minimum price for alcohol per standard serving. According to Dr. Stockwell, Alberta and the territories have not adopted standard minimum prices on alcohol to date, while Saskatchewan and New Brunswick have relatively high and effective minimum prices.[70] Witnesses explained that studies have shown that a minimum price of $1.71 per standard serving of alcohol would reduce the high-risk consumption of alcohol and its associated harms, including alcohol-related hospitalizations and deaths.[71] E. Monitoring and SurveillanceDr. Martin Laliberté highlighted the important role poison control centres play in the post-market surveillance of products that can pose risks to public health, including alcoholic beverages.[72] A national surveillance system that includes data from poison centres across Canada would enable public health experts to evaluate the number of calls received by poison control centres or emergency departments that are related to the use of pre-mixed drinks with high alcohol content, or other products of concern; and intervene more quickly. Dr. Laliberté explained that while such a system was currently under development at the national level, it will require sustained funding over time to be successful. F. National Alcohol StrategyIn order to address the broader issues related to alcohol, including the rising incidence of acute alcohol poisonings in Canada, the Committee heard it is necessary to update the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction’s National Alcohol Strategy.[73] This strategy was developed in 2007 in collaboration with representatives from all levels of government, industry, Indigenous communities and not-for-profit organizations. It contains 41 recommendations that focus on the availability of alcohol; health promotion and education; health effects of alcohol and substance abuse treatment; and safer communities. Many of the strategy’s recommendations have been implemented or are currently in the process of being implemented. However, the Committee heard that there is a need to update and renew efforts to implement this strategy, in light of new data and the rising heath and economic costs of alcohol abuse in Canada. COMMITTEE OBSERVATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONSThe Committee is very concerned about the health and safety risks posed by highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages to Canadians in general and to youth in particular. The problematic nature of these drinks was succinctly summarized by Dr. Martin Laliberté, Emergency Physician and Toxicologist, McGill University Health Centre, when he stated: One, the can is too big; two, there’s way too much alcohol in the can; three, the high sugar content masks the taste of alcohol; four, the can is too cheap; five, packaging and labelling is appealing to teenagers; and six, marketing strategies target young people.[74] The Committee agrees with witnesses that the harms posed by these beverages can be addressed through stricter regulation of these products, including limiting their alcohol content to the equivalent of one standard serving per container; addressing taxation and pricing incentives; introducing labelling requirements for alcoholic beverages; and placing new restrictions on the marketing of these products. The Committee heard that it is also necessary for governments to make greater efforts to enforce existing regulations, particularly in relation to the marketing of alcoholic beverages in Canada. The Committee’s study also highlighted the problematic nature of the promotion of the mixing of caffeine and alcohol either by caffeinated energy drink companies or alcoholic beverages that are being promoted by manufacturers as energy drinks. The Committee believes that confusion surrounding this issue is reinforced by the Food and Drug Regulations that allow for alcoholic beverages to contain flavoring ingredients that contain naturally occurring caffeine. The Committee believes that these issues need to be more closely examined by Health Canada. Finally, the Committee’s study also demonstrated that there is a need for renewed efforts to address problematic alcohol use in Canada through a broad range of measures. Ms. Athéna Gervais’ death is only one of the hundreds of deaths that occur every year in Canada as a result of acute alcohol poisoning. It may be time for the Government of Canada to consider an approach to alcohol regulation that is more in line with its efforts to prevent tobacco use. The Committee therefore recommends: Restrictions on the Alcohol, Sugar and Caffeine Content in Highly Sweetened Pre-mixed Alcoholic Beverages Recommendation 1 That Health Canada restrict the alcohol content in highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages to that of one standard serving of alcohol in Canada, or 13.5 grams or 17.05 millilitres pure of alcohol through the Food and Drug Regulations. Recommendation 2 That Health Canada set the sweetness threshold of highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages at 5% under the Food and Drug Regulations to restrict the place of sale of these products. Recommendation 3 That Health Canada restrict the caffeine content of alcoholic beverages in Canada to 30 milligrams per standard serving of alcohol through the Food and Drug Regulations, which is in line with current voluntary standards set by the Canadian Association of Liquor Jurisdictions. Labelling and Packaging Recommendation 4 That Health Canada require through the Food and Drug Regulations that all alcoholic beverages for sale in Canada include on their labels, the number of standard servings of alcohol contained in the beverage. Recommendation 5 That Health Canada require through the Food and Drug Regulations that all alcoholic beverages for sale in Canada clearly label the amount of sugar, calories and caffeine, as well as other stimulants contained in these beverages. Recommendation 6 That Health Canada prohibit the labelling and packaging of alcoholic beverages in a manner that could be considered appealing to young persons through the Food and Drug Regulations. Marketing and Branding Recommendation 7 That the Government of Canada amend section 7 of the Food and Drugs Act to prohibit the advertising of alcoholic beverages in a manner that could be considered appealing to young persons. Recommendation 8 That the Government of Canada consider directing the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission to review its Code for broadcast advertising of alcoholic beverages to determine whether or not it should also apply to new forms of digital media, including social media and the Internet. Recommendation 9 That Health Canada prohibit producers from branding or naming alcoholic beverages in a manner that makes reference to their product strength, excessive consumption or makes light of alcohol dependence through the Food and Drug Regulations. Recommendation 10 That Health Canada consider the potential issues surrounding the use of a brand name of an authorized caffeinated energy drink by an alcoholic beverage company. Recommendation 11 That Health Canada look at the issues surrounding the promotion activities of caffeinated energy drink manufacturers in Canada to determine whether they promote the mixing of these beverages and alcohol and report publicly on its findings. Pricing and Taxation Recommendation 12 That the Government of Canada either: a) set excise taxes for all alcoholic drinks at a fixed rate per standard serving indexed to inflation; or b) set excise tax rates for highly sweetened pre-mixed alcoholic beverages at the same rate as those for spirits. Recommendation 13 That the Government of Canada in collaboration with provinces and territories set a national minimum price for a standard serving of alcohol, which is indexed to inflation. Monitoring and Surveillance Recommendation 14 That the Government of Canada provide sustained funding for the development of a national poison centre surveillance system to improve the monitoring of consumer products that could pose a risk to human health and safety. National Alcohol Strategy Recommendation 15 That Health Canada work in collaboration with the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction, provincial and territorial governments, non-governmental organizations, industry, and Indigenous communities to update and renew the 2007 National Alcohol Strategy. [1] House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (HESA), Evidence, 30 April 2018, 1635 (Ms. Catherine Paradis, Senior Researcher and Policy Analyst, Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction). [2] Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, “Acute Alcohol Poisoning and Sweetened Alcoholic Beverages,” written submission provided to HESA, May 2018 and Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director and Adam Sherk, Doctoral Candidate, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, “Inquiry into high alcohol, high sugar pre-mixed alcoholic beverages,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. [3] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Health, “Minutes of Proceedings,” 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 19 March 2018. [4] House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (HESA), Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2018, 1545 (Ms. Karen McIntyre, Director General, Food Directorate, Health Products and Food Branch, Health Canada). [5] Food and Drugs Act, R.S.C, 1985, c. F-27. [6] Food and Drug Regulations, C.R.C, c. 870. [8] Ibid. [9] Ibid., 1555 (McIntyre). [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Labelling Requirements for Alcoholic Beverages, 12 March 2018. [14] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1755 (Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria). [15] Ibid. [16] Excise Act, 2001, S.C. 2002, c. 22. [17] Excise Tax Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. E-15. [19] Ibid., 1545 (McIntyre). [20] Butt, P., Beirness, D., Gliksman, L., Paradis, C., & Stockwell, T., “Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking,” Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction, 2011, p. 14 [21] Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, “Acute Alcohol Poisoning and Sweetened Alcoholic Beverages,” written submission provided to HESA, May 2018. [22] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1820 (Dr. Réal Morin, Vice-President of Scientific Affairs, Institut national de santé publique du Québec). [23] HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018, 1725 (Mr. Jan Westcott, President and Chief Executive Officer, Spirits Canada). [24] Ibid. [25] Association pour la santé publique du Québec, “The Dangers of Pre-Mixed Drinks Combining High Alcohol Caffeine and Sugar Content,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. [26] Ibid. [28] Ibid., 1635 and 1705 (Paradis). [32] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1800 (Ms. Lucie Granger, Director General, Association pour la santé publique du Québec). [34] HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018, 1600, (McIntyre) and Association pour la santé publique du Québec, “The Dangers of Pre-Mixed Drinks Combining High Alcohol Caffeine and Sugar Content,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. [36] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1800 (Granger). [37] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018 (Morin, Stockwell) and HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018 (Sacy, Paradis, Laliberté). [38] Ibid. [39] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1815 (Dr. Maude St-Onge, Medical Director, Centre antipoison du Québec). [40] Ibid. [42] Ibid. [43] Ibid. [44] Ibid. [47] Association pour la santé publique du Québec, “The Dangers of Pre-Mixed Drinks Combining High Alcohol Caffeine and Sugar Content,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. [48] Bill 170, An Act to modernize the legal regime applicable to liquor permits and to amend various other legislative provisions with regard to alcoholic beverages. [49] HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018 (Morin, Stockwell) and HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018 (Sacy, Paradis, Laliberté). [55] HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018, 1745 (Dr. Martin Laliberté, Emergency Physician and Toxicologist, McGill University Health Centre). [57] Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director and Adam Sherk, Doctoral Candidate, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, “Inquiry into high alcohol, high sugar pre-mixed alcoholic beverages,” reference document submission to HESA, May 2018. [59] Tim Stockwell, PhD, Director and Adam Sherk, Doctoral Candidate, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, “Inquiry into high alcohol, high sugar pre-mixed alcoholic beverages,” written submission to HESA, May 2018. [64] HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018 (McIntyre, Paradis) and HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1840 (Granger). [69] HESA, Evidence, 30 April 2018, 1635 (Paradis) and HESA, Evidence, 9 May 2018, 1800 (Stockwell). |