FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INTRODUCTION

In 1921, Agnes Campbell Macphail became the first women to be elected to the House of Commons. Since then, the participation and roles of Canadian women in politics have grown substantially. Yet in 2018, women remain under-represented at every level of government in Canada, including in Canada’s Parliament. According to Statistics Canada, women represent 35% of all legislators in Canada.[1]

Increasing women’s participation in electoral politics is essential for achieving greater gender equality. Having more women in elected office is about more than achieving equality in a traditionally male-dominated field; it could also have significant effects on public policy:

It is undeniable that women's increased political participation as elected officials leads to better social, economic and political outcomes for everyone. From increased attention on issues that impact women's lives to an often more collaborative working environment, increasing meaningful representation of women in politics is a crucial factor in strengthening Canada's democracy.[2]

Recognizing the positive effects that increasing women’s representation in electoral politics would have on Canadian society, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (the Committee) agreed on 1st March 2018 to undertake a study on barriers facing women in politics. The Committee adopted the following motion:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the Committee undertake a study, for the duration of six (6) to eight (8) meetings, on barriers facing women in politics, including, but not limited to:

- barriers in the candidate recruitment and selection process, male‑dominated professional networks, and mentorship opportunities;

- barriers in the House of Commons, such as party discipline, gender‑biased media treatment and inequity in professional development and support.[3]

The Committee received testimony from 33 witnesses—18 of whom appeared as individuals, with the remainder representing 10 organizations. In addition, the Committee was briefed by officials from the following government departments and agencies: the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women,[4] the Privy Council Office, Statistics Canada and Elections Canada. The testimony was received during six meetings held from 5 June 2018 to 26 September 2018. As well, the Committee received 12 written briefs from organizations and individuals, many of which had appeared before the Committee, along with written speaking notes and follow-up responses to questions from Committee members. Appendix A of this report includes a list of all witnesses and Appendix B includes a list of all submitted briefs.

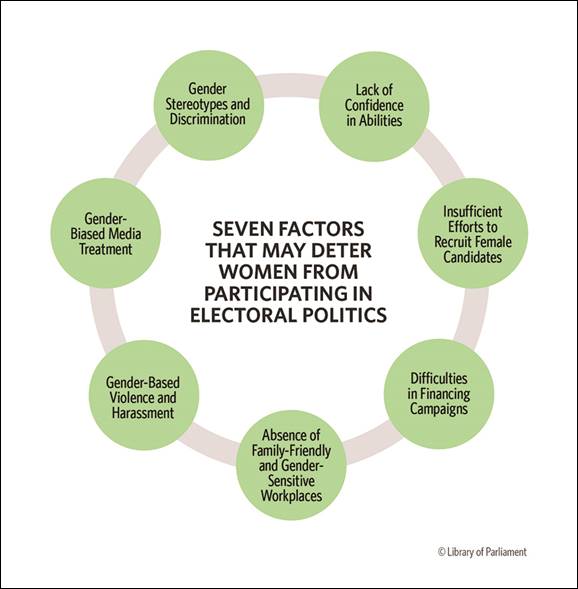

Figure 1—Seven Factors That May Deter Women from Participating in Electoral Politics

The Committee’s report provides an examination of and possible solutions to address:

- 1) the relatively low representation of women at all levels of electoral politics in Canada;

- 2) barriers facing women when making the choice to enter electoral politics, such as women’s interest and involvement in political activities; gender stereotypes and discrimination; and women’s political ambition and confidence;

- 3) barriers in the recruitment of women from diverse backgrounds to run for elected office, including of the role of electoral district associations, local search committee and political parties;

- 4) barriers facing women running for elected office, such as nomination and election campaigns rules and procedures; the political and electoral systems; incumbency status; the choice of riding; and campaign expenditures; and

- 5) barriers facing female elected officials, such as the lack of family-friendly and gender-sensitive political workplaces; gender-biased media treatment; and gender-based violence and harassment.

The Committee notes that while the majority of the witnesses that testified before it provided a number a barriers that make it difficult for women to enter or remain in electoral politics, one witness noted that some women might not face challenges at all.[5]

The Committee’s report is intended to provide guidance to the Government of Canada on measures that could be implemented to help improve the representation of women in electoral politics in Canada. Committee members greatly appreciate the contributions of witnesses who offered their knowledge, ideas and insights on the subject of barriers facing women in electoral politics.

OVERVIEW OF WOMEN’S REPRESENTATION IN ELECTORAL POLITICS IN CANADA

Over the years, Canada has made a number of international commitments regarding women’s participation in decision-making and in the public and political life of their country. For instance, the United Nations Economic and Social Council resolution number 1990/15 called on governments and other stakeholders to aim at having women hold at least 30% of leadership positions.[6] In 2018, few parliaments, legislatures, local or municipal governments have reached this threshold. The sections that follow provide an overview of women’s representation in the Parliament of Canada, in provincial and territorial legislatures and in municipal and local governments.

A. Women in the Parliament of Canada

Women first surpassed the 20% mark in the House of Commons in the 1997 general election when they won 20.6% of seats. As of 5 December 2018, women held 91 of the 335 occupied seats in the House of Commons, representing 27.2% of all Members of Parliament.[7] According to a representative from the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women, 4.4% of the seats in the House of Commons are occupied by visible minority women and 0.9% by Indigenous women.[8]

Female candidates’ representation in federal general elections as well as the percentage of women in the House of Commons, has increased over the years. Data show that among all elected candidates, the percentage of elected candidates who identify as women is generally lower than the percentage of female candidates, indicating that female candidates are being elected at a lower rate than male candidates (see Figure 2).

Figure 2—Percentage of Female Candidates and Women Elected in Federal General Elections

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Parliament of Canada, “Women Candidates in General Elections - 1921 to Date” and from Elections Canada, Past Elections.

Although women’s representation in the House of Commons is at an all-time high, it “still falls below the United Nations' recommendation of having at least 30% as the critical threshold for women in decision-making roles.”[9] Canada ranks 60th of 193 countries worldwide for the representation of women in single or lower houses of national parliaments.[10] According to a representative from the Office of the Co‑ordinator, Status of Women, “[t]hese numbers point to continued barriers to women's equal participation in democracy, indicating ongoing systemic discrimination and persistent unconscious bias.”[11]

Women’s representation in the Senate is generally higher than in the House of Commons. In Canada, senators are not elected; rather, they are appointed by the governor general, a power exercized on the advice of the prime minister. As of 5 December 2018, women occupied 46 of the 101 occupied seats in the Senate, representing 45.5% of senators currently in office.[12] A representative from the Privy Council Office stated that women represented 58.5% of the current government’s appointments to the Senate.

B. Women in Provincial and Territorial Legislatures

The representation of female legislators in provincial and territorial legislatures varies greatly across the country, from 10.5% in the Northwest Territories to 42.4% in Quebec, as shown in Figure 3. Several provinces and territories have reached or surpassed the 30% threshold for women in their legislature; however, only Quebec and Ontario have reached the parity zone, the zone between 40% and 60%.

Figure 3—Percentage of Female Legislators in Provincial and Territorial Legislature (2018)

Note: As of 5 December 2018, results of the 2018 Ontario general provincial elections were not official. Data for New Brunswick and Quebec are based on the makeup of the provincial legislatures as of 5 December 2018. Data from other provinces and territories are based on the makeup of the provincial and territorial legislature as of 1st October 2018.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from provincial and territorial legislatures, political parties and Members of Legislative Assemblies’ personal websites.

Madeleine Redfern, Mayor of Iqaluit, stressed the fact that, in Nunavut, politics goes beyond the local, territorial and federal governments: Inuit land claim organizations and regional Inuit associations are also political entities.[13] Ms. Redfern stated that these organizations often have a low proportion of women in leadership positions and that they sometimes have designated non-voting position for Inuit women on their boards of directors. She added that the under-representation of Inuit women in these organizations can create situations in which decisions taken do not reflect the views and priorities of the community as a whole.[14]

The Committee heard that there are programs to support women in electoral politics in many provinces and territories, such as the Campaign School for Women: Leaders in Action in Nova Scotia, “a course that prepares graduates to run for public office, organize campaigns, or pursue non-elected political roles” and programs “to increase gender parity in elected positions through training, mentoring, or communities of practice” in Alberta.[15]

C. Women in Municipal and Local Governments

As is the case for the other two orders of government, the proportion of women elected at the municipal level has increased over the years, but women remain under-represented as municipal councillors and mayors (see Figure 4). Data from 2015 shows that, on average, women represent 18% of mayors and 28% of municipal councillors in Canada.[16]

Figure 4—Representation of Women as Municipal Councillors in Canada

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 2015—Municipal Statistics: Elected Officials Gender Statistics and Federation of Canadian Municipalities, 2012—Municipal statistics: elected Officials Gender Statistics.

The Committee heard that the proximity and non-partisanship of municipal politics may be appealing to women[17] and that municipal politics often serve “as an incubator or a springboard for moving to other levels of provincial and federal politics.”[18] Karen Sorensen, Mayor of Banff, who appeared as an individual, told the Committee:

One of the big draws to school boards and municipal politics is that you get to be at home. I don't fly to Ottawa every Sunday, or even up to Edmonton. For me, that was a very big part of it. Honestly, for me, it's the partisan piece. I'm happy not to have a party. I'm happy to make decisions and be elected and stand on points that reflect my values. I totally embrace diversity even at our small council table in the Town of Banff, but I can always feel confident that I can speak my mind, make decisions, and vote in a way that is based on my values. To me, that is precious.[19]

Women are also under-represented in Indigenous governments. In 2015, Indigenous women represented 30.5% of band councillors on First Nations of Canada band councils.[20] As well, according to a representative of the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women, women represent approximately 17% of band chiefs in First Nations communities.[21]

CHOOSING TO ENTER ELECTORAL POLITICS

Deciding whether to enter electoral politics is a daunting task for anyone; however, women may face unique and specific barriers because of their gender. According to Thérèse Mailloux, Chair of the Board of Directors of the Groupe Femmes, Politique et Démocratie, “[t]oo often, the burden is placed on women to enter politics, but they are up against millennia of systemic barriers that make it very difficult for them to run for office.”[22]

The sections that follow describe the challenges women may face when deciding whether to enter electoral politics, including their interest in politics and involvement in community organizations; gender stereotypes and discrimination; and political ambition and confidence.

A. Women’s Interest in Politics and Involvement in Community Organizations

Data show that women in Canada tend to be less interested in politics than men: in a 2013 Statistics Canada survey, 24% of men reported being "very interested” in politics, compared to 15% of women, and 19% of men reported being “not very interested” in politics, compared to 25% of women.[23] Data showed that women and men with more education and with higher incomes are more likely to hold “positions in government and to participate in civic and political activities.”[24]

The Committee was also told that, in some instances, men and women participate in politics in different ways. For instance, according to 2013 Statistics Canada data, women are:[25]

- less likely than men to be members of political parties and to attend a public meeting;

- less likely than men to share their opinions on the Internet or in newspapers or to speak up in meetings;

- more likely than men to boycott or choose a product for ethical reasons;

- more likely than men to express interest in joining a school group, neighbourhood, civic or community association; and

- as likely as men to report attending a demonstration or march; wearing political badges or t-shirts; displaying lawn signs in support of or against a political or social cause; and signing an Internet petition.

The Committee was informed that data collected by Statistics Canada on certain social factors cannot be released because of small sample sizes, and increased funding from the federal government to improve the survey may allow for improvements in these areas.[26]

Even though women report being less interested in politics, Canadian women generally vote at higher rates than men. For instance, during the last three federal general elections, Canadian women voted at higher rates than men: 68% of women compared to 64% of men.[27] A representative from Elections Canada told the Committee that this pattern was observed in all age groups, except for people aged 75 years and over, where men voted at higher rates than women.[28]

As women tend to live longer than men, and mobility challenges and other disabilities may develop with age, older women may find it more difficult than other groups to get to a voting booth.[29] To increase voter turnout, the Honourable Eleni Bakopanos, National Board Member of Equal Voice, suggested including candidates’ pictures on the voting ballot to encourage women who have literacy issues to vote.[30]

As well, reasons given for not voting differ between women and men: 2013 Statistics Canada data show that women are more likely than men to indicate “feeling uninformed” and feeling “voting would have no impact” as their reasons for not voting.[31] The Committee heard that Elections Canada will be releasing new resources for educators in the fall of 2018 to “build the interest, skills, and knowledge required to be active citizens.”[32]

According to a representative from Statistics Canada, women tend to spend more time on local and civic issues, or volunteering for schools and clubs, because they may perceive these activities as more important than volunteering for a political party.[33] The Committee heard that community leadership work is often not recognized as political. For instance, Jane Hilderman, Executive Director of the Samara Centre for Democracy, explained that female finalists for the organization’s Everyday Political Citizen initiative often do not see their engagement as political.[34] Nancy Peckford, Executive Director of Equal Voice, explained that the organization decided to use inclusive language to try to appeal to and recruit young women from diverse backgrounds in its Daughters of the Vote initiative:

[T]here are lots of other women who would have not, I think, seized that moment to make an application, except for how we framed the opportunity, which was by asking the following. How do you lead in your community? How are you connected? How are you engaged? What does leadership look like to you? What's your vision for leadership? How do you want to make a difference? It was questions like those that, I think, rendered the opportunity more inclusive.[35]

Women's motivation to enter electoral politics is generally about trying to be engaged,[36] to create real change and to help people and their communities.[37] When women enter politics, they often do not begin with a partisan affiliation.[38]

As well, while many women are community leaders, they are often not connected to formal political spaces; they need to be invited to participate in these spaces, such as in riding associations, or party conventions.[39] Jane Hilderman stated that it is important to change the meaning of “be[ing] political” and help women connect their community efforts to formal politics.[40]

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada increase funding to Statistics Canada with the goal of expanding survey data collection about the participation and engagement of diverse groups of women in political activities, including, but not limited to, women’s leadership in community work and women’s participation and engagement in volunteering and donating to a political party.

Observation 1

The Chair of the Committee, on behalf of the Committee, will send a letter to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Procedures and House Affairs (PROC) to ask that PROC consider studying initiatives that could eliminate any potential gender bias linked to the design of voting ballots.

B. Gender Stereotypes and Discrimination and Women’s Participation in Electoral Politics

Socialization, gender roles, perceptions of appropriate career paths for women, and stereotypes or unconscious bias about leadership roles continue to be barriers for women in electoral politics.[41] These barriers can influence the ways female politicians are perceived by others and how they perceive themselves.[42]

The Committee heard that there are two types of sexism: implicit and explicit. Melanee Thomas, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Calgary, noted that implicit sexism, the internalized bias against women based on gender norms and stereotypes, is unconscious and is found among women themselves. In contrast, explicit sexism is based on gender stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination; explicit sexism is more overt. She told the Committee that, according to her research, approximately one in five Canadians holds explicit sexist views, and that men and older people are more likely than women to hold these views. In her study, individuals who held explicit sexist views rated competencies, perceived intelligence, perceived likeability and perceived warmth significantly lower when the example candidate’s credentials were associated with a female name.[43]

“ [W]omen have internalized this explicit sexism they're seeing in the political system, and that in turn is driving down their political interest and their confidence in their ability to be a political actor and driving down their political ambition.”

Melanee Thomas, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Calgary, as an individual

Explicit sexism has more concrete negative effects on women in politics than implicit sexism. For instance, Melanee Thomas told the Committee that “a lot of women have internalized this explicit sexism they're seeing in the political system, and that in turn is driving down their political interest and their confidence in their ability to be a political actor and driving down their political ambition.”[44] As well, individuals who hold explicit sexist views might not recruit or nominate female candidates, might not mentor and support women as politicians or party leaders, and might not vote for women.[45] However, the Committee heard that there is little research to support the idea that voters are influenced by the gender of candidates;[46] when given the opportunity, Canadians will vote for women.[47]

The Committee was told that politics is often associated with male gendered traits. Karen Sorensen explained that being competitive and powerful are traits that are typically associated with men, whereas typically female traits, such as empathy, nurturing and patience, are not tied to power or politics.[48] Brenda O’Neill, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Calgary, stated that men are perceived to possess the qualities necessary for leadership positions, such as assertiveness, and self-promotion, however, when a woman demonstrates these qualities she is often penalized.[49] For instance, “a male politician may be described as competitive and tough, but a female politician with the same qualities may be viewed as cold and aggressive.”[50] As well, sexist attitudes rely on stereotypes, such as women being too emotional or too nice for politics, to exclude women from political leadership.[51]

The Committee heard that, like other fields, women in electoral politics may struggle to gain recognition. A representative from the Office of the Co-ordinator, Status of Women explained that women working in traditionally male-dominated fields, such as politics, tend to have their leadership skills judged more harshly than their male counterparts, and that female politicians from racialized communities tend to experience the most hostility.[52]

The Committee was told that barriers to women’s political participation can only be removed once society’s attitudes about gender change.[53] To do so, several witnesses pointed to role modelling by women in electoral politics for children and young people as an effective strategy to combat gender norms and stereotypes about politics.[54] Daniela Chivu recommended including the topic of gender equality in education systems in Canada and suggested that Members of Parliament promote the United Nations’ “HeforShe” campaign, in order to continue to mentor boys concerning gender equality, consent, and respect.[55]

Natalie Pon explained that women need to be able to talk about the sexism that they experience in politics without being told to be tougher or to “suck it up.” However, she also suggested that if women could move past sexist comments, put their name forward and win elections, there would be a positive shift in attitudes towards women in politics.[56]

1. Caregiving and Family Responsibilities

The Committee heard that gender stereotypes perpetuate ideas that women belong in the home or in a caregiving role, and that men belong in electoral politics; as a result, society does not expect to see women in politics.[57] According to a Statistics Canada representative, the presence and age of the youngest child in the house has a notable impact on women’s work hours outside the home, but very little effect on men’s work hours; women with children under the age of six work fewer hours a week outside the home, on average, than other women.[58]

While campaigning, women’s ability to balance family responsibilities and running for elected office may receive attention in ways that men’s private and family lives do not:

Sadly, I believe there continues to be a suggestion that mothers who pursue political careers are not thinking of the best interests of their children, or having a mom in politics is somehow more damaging than having a dad in politics. In politics … women who make a point of making time for their children are still labelled as a weak link and not focused on the job at hand, yet the same effort is praised in men who are labelled as great dads for taking time for the kids.[59]

Witnesses explained that balancing political work and family life can be a challenge; expectations and responsibilities of motherhood continue to act as deterrents to women considering political careers.[60] Witnesses also explained that long sitting hours and the need to work away from home for extended periods of time can be difficult for elected officials with children.[61] Kayleigh Erickson cited the high cost of childcare as a barrier to women’s participation in electoral politics.[62] Nancy Peckford referred to research that found women’s hesitancy to run for political office is at times a result of a fear of jeopardizing the financial stability of their families, or the professional trajectories of their partners.[63]

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada develop and implement a public education campaign whose goal is to positively shift how women in electoral politics are perceived.

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada, at the next meeting of Canada’s Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers responsible for Education and for the Status of Women, encourage all jurisdictions to incorporate the topics of gender equality, gender stereotypes and women’s participation in politics into their education curricula with the goal of increasing women’s political participation and building girls and young women’s confidence.

C. Women’s Political Ambition and Confidence

Research suggests that in Canada, levels of political ambition differ between men and women. Melanee Thomas explained that her most recent research found that 1% of women, compared to 5% of men, indicated having the ambition of seeking elected office.[64] As well, research conducted by William Cross, Professor in the Department of Political Science at Carleton University, concluded that among political candidates of all three official parties in the 2015 federal general election, there was a significant difference in political ambition between genders: men indicated that they had decided to pursue a career in politics at a younger age than women, and men were 40% more likely than women to believe that running for federal office was the logical next step in their political careers.[65] Witnesses stated that, while women indicate a lower level of political ambition than men, there are more than enough women who have political ambitions for parties to run gender-balanced slates of candidates.[66]

The Committee was told that some women have a tendency to doubt or downplay their skills or lack confidence in their political abilities.[67] For example, Brenda O’Neill shared this personal story:

I have a Ph.D. in political science, and I study women in politics. When I first received the request to come and speak to you, my first response was, “What could I possibly have to say that would be of any importance to this committee?” It was the people around me who told me, “No, you have to participate.”[68]

Brenda O’Neill said that women who are interested in entering electoral politics may choose to run at the municipal level because they perceive this level to be easier, or because they should start at a “lower” level.[69]

The Committee heard that supporting women’s empowerment is necessary for women’s overall success,[70] and that it is important to emphasize and recognize all types of women’s participation in politics.[71] As poverty is one of the barriers to women’s empowerment and political participation,[72] witnesses suggested several measures to reduce the negative effects poverty can have on women, such as applying gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) to the Poverty Reduction Strategy and mainstreaming the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action in the Poverty Reduction Strategy, as well as ensuring coordination between the National Housing Strategy and the Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence.[73]

Since confidence building starts during childhood,[74] witnesses emphasized the importance of incorporating changes to the education system to empower girls and young women and encourage them to engage in politics,[75] but also that the system should educate both girls and boys about gender equality, and socialization related to politics.[76] In a submitted brief, Lourdine Dumas and Solange Musanganya recommended that a bilingual, multidisciplinary educational platform focused on women’s leadership be created and made available online, offline, and through a mobile app.[77] In addition, Marjolaine Gilbert, Coordinator of the Réseau femmes et politique municipale de la Capitale-Nationale, suggested that gatherings in town councils and internship opportunities be established for female students.[78]

Projects that aim to address systemic barriers for women’s participation in political and civic life, such as Equal Voice’s Daughters of the Vote initiative, can be funded under Status of Women Canada’s Women’s Program.[79] Several witnesses asserted that the Government of Canada should continue to provide funding to organizations that support women’s empowerment and political engagement.[80] The Honourable Eleni Bakopanos stated that Elections Canada could be more engaged in encouraging women’s political ambition, through initiatives aimed at engaging young people.[81]

The sections that follow describe initiatives that could be undertaken to help empower women and increase their representation in electoral politics.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada continue to strengthen the application of Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) in all federal departments and agencies’ programs, initiatives, and strategies.

1. Campaign Schools for Women

Witnesses told the Committee that non-partisan training, particularly campaign schools, can be very beneficial to women who are considering entering electoral politics.[82] Witnesses highlighted several areas in which campaign schools can be helpful: they can provide women with networking and mentorship opportunities,[83] and anti-harassment and media training.[84] Campaign schools can also help increase women’s confidence and allow them to learn practical skills such as fundraising and effective door-knocking approaches.[85]

Witnesses encouraged the Committee to consider strategies to expand access to campaign schools and training for women.[86] Among the recommended strategies were increasing funding to existing organizations that provide campaign schools;[87] offering government-developed training programs and campaign-schools;[88] providing grant opportunities to cover the costs of campaign schools; and providing online courses.[89]

2. Access to Role Models and Mentorship and Networking Opportunities

Witnesses stated that when women see other women in politics, they are more likely to be interested, participate, and see themselves in politics.[90] Having access to role models, including to male role models, and to mentorship and networking opportunities, both at the formal and grassroots level,[91] is an integral part of women’s decisions to enter electoral politics.[92] Mentorship and networking help women acquire the skills and supports needed to be successful in politics.[93] Both mentorship and networking can also show women that they are not alone in the political race,[94] increase their confidence,[95] and teach skills and build capacity.[96]

Jenelle Saskiw explained that in rural areas, networking can be very different for men and women, and that there needs to be an increase in networking spaces for women in these contexts. In addition, she emphasized that establishing better interactions between election periods is important, especially for candidates who ran and were not successful.[97]

Sylvie Asselin, President of the Réseau femmes et politique municipale de la Capitale-Nationale, explained that a lack of funding to organizations providing mentorship and networking opportunities remains a barrier to women accessing these types of opportunities.[98] Kayleigh Erickson called for greater funding for these opportunities,[99] and suggested that women’s mentorship should be integrated into existing youth programs, such as model parliaments, to help alleviate the burden of providing these opportunities on organizations that are often under-resourced.[100]

Recognizing the positive effects that role modelling and mentorship can have, the Committee would like to encourage current and past elected officials to provide mentorship to both newly elected women, and women seeking elected office.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada increase funding for organizations and projects that:

- support the political engagement and empowerment of diverse groups of women;

- provide relevant training, both in person and online, for women interested in seeking elected office;

- provide women with internships and similar opportunities in political workplaces;

- provide mentorship, role modelling, networking opportunities and guidance to women in order to increase their confidence and willingness to take risks and encourage them to seek elected office; or

- involve men in efforts to encourage women to run for elected office.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada encourage elected officials to engage women in their communities by providing guidance, job shadowing and networking opportunities, including through local women’s councils and youth councils.

RECRUITING FEMALE CANDIDATES FROM DIVERSE BACKGROUNDS

The Committee heard that the under-representation of women in electoral politics may indicate difficulty to recruit female candidates to run for elected office. For instance, at the municipal level, mayors have reported that they find it difficult to recruit female candidates, and that this is especially true for women under 35 years of age.[101]

Witnesses explained that women often need to be asked multiple times or need to be convinced to run for political office,[102] and as such political parties have to actively recruit women,[103] instead of encouraging women to put themselves forward.[104] William McBeath said:

I think it's also the case that we've relied for the most part on those individuals who have structural and situational barriers to their actually getting to the position of election. We're relying on women to do it as opposed to the demanders of nominees. We're relying on the supply, which is the women and the very ones who have those barriers in place. We're waiting for them to somehow magically come forward when we know it's not a level playing field for women and men in politics. This is the problem. When you have riding presidents saying we have one woman who's the leader of the party and we don't really need any others, this isn't true.[105]

However, women do not lack the education and experience to hold an elected position: according to a representative from Statistics Canada, women are more likely than men to possess a university degree at the bachelor level or higher; and women under 25 years of age are more likely than men to be working after obtaining their university degree.[106]

Candidate recruitment and selection processes were cited as two of the main contributors to women’s under-representation in politics.[107] Jeanette Ashe, Chair, Political Science, Douglas College, explained that her research has found that men are up to six times more likely than women to be selected as candidates for elected office.[108] Some witnesses argued that the under-representation of women in electoral politics is caused by a lack of demand for female candidates,[109] stemming from existing bias against women among political party officials responsible for recruiting and selecting candidates for nominations.[110] Nancy Peckford told the Committee that, in the 2015 federal general elections, “[a] third of Canadians were going to the polls and they didn't have a single woman to choose from,” despite polls indicating that Canadians want to see more female candidates.[111]

Figure 5—Percentage and Number of Candidates Identifying as Women in the 2015 Federal General Elections, by political party

Note: Figure 5 presents data only for registered parties for which more than 10 confirmed candidates and at least one female candidate ran.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Parliament of Canada, “Women Candidates in General Elections - 1921 to Date” and from the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Report on the 42nd General Election of October 19, 2015, 2016.

Among solutions suggested by witnesses to increase women’s representation in electoral politics, we find: adopting clear language that requires electoral district associations (EDAs) to recruit female candidates;[112] denouncing and enforcing a zero-tolerance policy for incidents of sexism and discrimination; being mindful of creating accessible spaces in formal political institutions and organizations for women; establishing a non-partisan coalition dedicated to encouraging women to enter electoral politics;[113] and involving everyone, including men, in increasing women’s representation in electoral politics.[114]

Witnesses noted that EDAs, local search committees and political parties all have a role to play in increasing women’s representation through candidate recruitment and their selection processes.

In a submitted brief, the Réseau des tables régionales de groupes de femmes du Québec told the Committee that equality could be set as an objective in the Canada Elections Act to send the message that gender equality is important.[115]

A. Increasing the Representation of Women from Diverse Backgrounds in Electoral Politics

Women from minority groups may face additional barriers to entering electoral politics.[116] Witnesses emphasized that the lack of representation of women from diverse backgrounds in politics, including racialized women, Indigenous women[117] and women who are transgender, means that these groups are excluded in decision-making processes.[118] Over the years, there has been an increase in the proportion of elected women in rural ridings[119] (from 10% in the early 2000s to 24% in 2015), but women running in rural ridings still face specific barriers, such as, in some cases, fragile local economies.[120] Louise Carbert, Associate Professor of Political Science at Dalhousie University, recommended that initiatives to increase women’s representation in rural ridings in legislatures and similar bodies should focus on easing economic distress in these areas.[121]

“ [O]ur parliaments should be representative of the countries they serve. Gender is a salient characteristic. Women are diverse, and that diversity should be present within our parliaments.”

Sarah Childs, Professor, Politics and Gender, Birkbeck, University of London, as an individual

Witnesses agreed that a diversity of opinion is advantageous to politics, and that a woman can be affiliated with any political party and should not be criticized for her choice of partisanship.[122] Sarah Childs, Professor of politics and gender, Birkbeck, University of London, said that “our parliaments should be representative of the countries they serve. Gender is a salient characteristic. Women are diverse, and that diversity should be present within our parliaments.”[123] The Committee was told that a woman who wants to be in electoral politics is the ideal candidate for political office,[124] and women from diverse backgrounds should have equal opportunity to run.[125] The Committee stresses the importance of both ensuring a diversity of opinion in politics and ensuring that the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is upheld.

Witnesses stressed the need for diverse parliaments, legislatures and local and municipal governments.[126] Increasing diversity in electoral politics would be beneficial for several reasons: it could change the culture of politics;[127] it could add diverse perspectives to decision-making which could improve policies; different issues could be brought forward; it could bring more role models and mentors; and it could make networking easier for women of all backgrounds and environments.[128] Witnesses explained that ensuring that women from diverse backgrounds, who defend various perspectives and are from all walks of life, are involved at all levels of electoral politics in Canada is crucial.[129] Yolaine Kirlew asserted that the visibility of women from diverse backgrounds in politics is important for teaching future generations that leadership comes from diverse backgrounds.[130]

Witnesses shared initiatives that could be undertaken to increase women from different background’s representation in electoral politics. In a submitted brief, the Diversity Institute at Ryerson University recommended implementing programs for women from diverse backgrounds to encourage them to enter electoral politics from an early age.[131] As well, the Committee heard that targets could be established to ensure adequate representation of women from diverse backgrounds in electoral politics and to ensure that they run in ridings or districts they are more likely to win.[132]

In a submitted brief, YWCA Canada recommended that any federal initiatives aimed at addressing women’s participation in electoral politics address the specific barriers faced by diverse and minority women, including racialized and Indigenous women. More specifically, the organization recommended that the Government of Canada, through the Indigenous Women’s Circle of Status of Women Canada, develop a strategy supporting Indigenous women in electoral politics. YWCA Canada also stated that consultations for a federal anti-racism strategy should include the perspectives of racially diverse and Indigenous women who wish to enter electoral politics, and include their recommendations in the final strategy.[133]

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories, consult and collaborate with diverse groups of women to develop a strategy to encourage women from diverse backgrounds to participate in electoral politics and a strategy supporting Indigenous women in electoral politics, and report back to Parliament on the implementation and outcomes of these strategies on an annual basis.

B. The Role of Electoral District Associations and Search Committees in the Recruitment of Female Candidates

The Committee heard about the importance of local search committees and EDAs in increasing the number of women who hold elected office.[134] William Cross explained that EDAs with active local search committees were significantly more likely to have female candidates for nomination contests than EDAS without search committees.[135] As well, Mr. Cross found that EDAs with women in leadership positions were more likely to have female nomination contestants because female leaders are more likely to seek out other women for nomination than men.[136] However, EDAs have a low number of female executives and EDA presidents are mostly men.[137] Dawn Wilson, Executive Director of the PEI Coalition for Women in Government, urged political parties to consider having equal gender representation, and diverse people among its search committee members.[138] Natalie Pon added that having more women involved in the grassroots process and on campaigns would bring change.[139]

William McBeath called for changes to the Canada Elections Act to allow for the establishment and permanent involvement of political action committees (PACs) in the search for and training of female candidates that are affiliated with specific parties. He explained that establishing PACs would allow for greater recruitment and nomination of female candidates, as PACs could provide continued and consistent support, answer all the questions women have and actively recruit female candidates.[140]

When asked about the role PACs could play in increasing the number of women running for elected office, Brenda O’Neill was very cautious and said that while PACs “can certainly help with the educative effect of teaching people what it actually means to run for office,”[141] they can become barriers to electing more women.

C. The Role of Political Parties in the Recruitment of Female Candidates

Political parties, especially their leaders, can play a key role in ensuring that women overcome barriers to elected office and in achieving gender equality in electoral politics.[142] The Committee heard that “[s]ystemic and structural factors impede women's access to politics by creating invisible barriers. Chief among the barriers — the greatest, we think — are the political parties' recruitment and selection processes.”[143]

“ Systemic and structural factors impede women's access to politics by creating invisible barriers. Chief among the barriers — the greatest, we think — are the political parties' recruitment and selection processes.”

Thérèse Mailloux, Chair, Board of Directors, Groupe Femmes, Politique et Démocratie

All political parties should bear the responsibility of fielding more female candidates and actively recruiting women for these positions.[144] In particular, the Committee was told that political parties should be examining their recruitment and selection processes to eliminate any sexism and bias that may implicitly be built into these processes and to recruit more women.[145] Melanee Thomas explained what these steps could look like for political parties:

What this means for parties and for organizers is that they actually should start saying no to candidates who volunteer or who are easy recruits from overrepresented groups. It means that leaders need to tell their organizers to find a set number of women to run. That number for parity in Canada is 169, so it's a low bar.[146]

Political parties are responsible for creating an environment in which women have equal opportunities;[147] to do so, parties can offer support to female candidates who might be unfamiliar with the electoral process, for example.[148] In a submitted brief, the Réseau des tables régionales de groupes de femmes du Québec recommended requiring that political parties create action plans that would include concrete measures to achieve gender equality and to report on their progress to chief electoral officers. To achieve goals set out in these action plans, political parties could be required to invest some of their subsidies into a fund to promote and support gender equality in politics.[149] As well, the Réseau des tables régionales de groupes de femmes du Québec made several recommendations regarding women from different backgrounds’ representation in electoral politics, such as:[150]

- requiring that a certain percentage of parties’ candidates be from racialized groups; and

- ensuring that parties’ national lists reflect the ethnocultural diversity of Canadians, and that these candidates are well-positioned to win seats.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada consider making changes to encourage gender equality and diversity in electoral politics; to ensure more transparency and consistency in nominations processes; and to require registered parties to publicly report on their efforts to recruit female candidates from diverse backgrounds after every federal general election.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada encourage registered parties and registered electoral district associations to set goals and publicly report on their efforts to nominate more female candidates, to achieve gender parity on their boards of directors, including in positions of leadership, and to establish search committees for candidates in federal general elections and by‑elections.

1. Offering Financial Incentives to Political Parties to Increase Women’s Representation in Electoral Politics

Because of the important role political parties play in the recruitment and the selection process of candidates for elections, some witnesses stated that political parties should be incentivized to increase the number of female candidates running in elections.[151] Witnesses recommended a number of ways in which political parties could be incentivized.

Firstly, several witnesses recommended that political parties receive financial incentives to field more female candidates in elections,[152] which some witnesses suggested doing at the federal level by amending the Canada Elections Act.[153] Witnesses shared the example of New Brunswick,[154] where changes were made to the formula for the public financing of political parties whereby votes “received by female candidates are weighted 1.5 times greater than votes received by male candidates.”[155] According to Kayleigh Erickson, this encourages political parties to run women in competitive and ridings they are more likely to win.[156]

As well, witnesses suggested that subsidies could be available to political parties who meet a certain threshold of female candidates or women elected. For instance, Jeanette Ashe suggested that thresholds for female candidates or candidates from other marginalized groups could be established and subsidies could be available for political parties who meet them.[157] In a submitted brief, the Réseau des tables régionales de groupes de femmes du Québec recommended subsidizing political parties based on the proportion of elected representatives who are women, rather than the proportion of candidates who are women once women represent more than 35% of those elected from the party.[158]

Furthermore, instead of providing financial incentives to political parties, William Cross suggested providing financing to “local EDAs that have more women on their executive or to local associations that have gender parity in their membership.”[159] Mr. Cross argued that such incentives might increase women’s participation in politics at the grassroots level, which might lead to more women seeking nominations.[160]

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada create a financial incentive for all registered parties to nominate more candidates who are women in general elections and by‑elections.

2. Quotas to Increase Women’s Representation in Electoral Politics

The Committee heard that one of the ways to rapidly increase the representation of women in electoral politics is to implement quotas. According to Brenda O’Neill, the implementation of quotas can rapidly eliminate stereotypes that are barriers to women’s participation in electoral politics:

Seeing more women in office acting as strong leaders would serve to dispel the stereotype that women are more suited to supportive roles than to leadership roles and are therefore unsuited to politics. It would also reinforce the role model effect. More women in political office increases the likelihood that women will see politics as an option for them. I think it would also help women to overcome the problem of feeling that they're not competent enough to engage in politics.[161]

Quotas have successfully increased women’s representation in electoral politics in a number of countries where they were implemented, such as France, Mexico, New Zealand, Rwanda and Spain.[162] According to Thérèse Mailloux, most of the “top 20 or 30 countries on the Inter-Parliamentary Union list have quotas prescribed by law or in their constitution, or quotas the parties impose on themselves.”[163]

The Committee was told that implementing quotas would send a strong message about the importance of gender equality.[164] Several witnesses recommended that quota systems be established to increase women’s representation in electoral politics in Canada. For instance, some witnesses recommended that political parties be required to field an equal number of female and male candidates in general elections,[165] and that gender parity in the federal government’s Cabinet be legislated.[166] Witnesses told the Committee that quota systems should aim to increase the number of female candidates parties put forward in elections;[167] provide incentives for parties, for instance financial incentives;[168] and be adapted to the Canadian political context.[169] In a submitted brief, the Groupe Femmes, Politique et Démocratie suggested that political parties be granted greater funding to “take concrete steps to bring parity to their lists of candidates before and during electoral campaigns.”[170]

There was a diversity of opinions on the use of quotas. Firstly, witnesses explained that quotas can reinforce the idea that women are elected because of their gender and not because of their ability or competence.[171] However, Brenda O’Neill told the Committee that, according to research, quotas tend to improve the quality of the elected candidates because “parties appear to be more careful of the skills they would like to see in their political nominees, rather than relying on short-hand mechanisms for selection such as gender and occupation.”[172]

Secondly, the Committee was told that quotas can create conflict between quota groups and non-quota groups, because diversity is not only about gender, but also about identity factors such as age, religion, sexuality and profession.[173] To that point, Rosie Campbell, Professor of Politics, Birkbeck, University of London and Sarah Childs advocated for the development of a “quota-plus” policy in order to “maximize the supply pool of women, and particularly to diversify the supply pool of women” to ensure that parliaments are representative.[174]

Finally, some witnesses said that quotas are an arbitrary metric that, once reached, can send the message that the issue for which the quota was implemented is settled.[175] For instance, William McBeath suggested that “[o]ftentimes, in order to meet the quota, political parties will nominate candidates in ridings in which they are unlikely — or even highly unlikely — to be successful. If they're not going to win in a general election, then this does nothing to further the cause of electing more women candidates to public office.”[176] Michaela Glasgo told the Committee that a “quota system goes against the very principle of democracy” and that voters “should be electing who they want to see in Parliament and in legislatures.”[177]

In order to increase women’s representation in electoral politics, Michaela Glasgo suggested focusing on grassroots initiatives that “bring women to the table,” such as asking competent women to get involved in politics, instead of implementing quotas.[178]

Observation 2

The Committee encourages registered parties to set voluntary quotas for the percentage of female candidates they field in federal elections and to publicly report on their efforts to meet these quotas after every federal general election.

WOMEN RUNNING FOR ELECTED OFFICE

Running for elected office is not an easy decision regardless of gender; however, the Committee heard that women may encounter barriers over the course of this process that their male counterparts do not. The sections that follow describe the challenges women may face during nomination and election campaigns, including those related to rules and procedures, incumbency status, the impact of the choice of riding on candidates’ success, and campaign expenditures.

A. Rules and Procedures for Nomination and Election Campaigns

The Committee was told that the rules and processes associated with nomination and election campaigns can be complicated,[179] and that decision-making within parties was described as “opaque.”[180] William McBeath explained that winning a nomination requires work and support in four areas: recruitment, training, fundraising and networking.[181] He added that:

[Winning a nomination] involves identifying, and occasionally persuading, a candidate to seek office; mentoring them when they encounter challenges; building a team of volunteers and professionals to support the nomination campaign; raising money to pay for nomination campaign activities; and connecting the candidate and her team with key stakeholders, influencers and voters in the constituency to build a winning coalition of members or supporters.[182]

Louise Carbert added that in nomination races in rural ridings, often small groups of people dictate which candidate they want to see go forward, and direct funding and support towards this candidate.[183]

According to William Cross, increasing the number of women elected starts with party nominations. He added that evidence suggests that when party members are given the option to nominate female candidates, they will do so.[184] In addition, early and long nomination campaigns are more likely to attract female contestants.[185]

Women may benefit from increased transparency and accountability in nomination and election campaign processes, as this would confirm that all candidates are subject to the same rules.[186] The Committee heard from Natalie Pon that the best way to support female candidates through the nomination and election process is to help them in concrete ways, such as in door-knocking, selling memberships and fundraising.[187]

1. Data on Selection and Nomination Processes at the Federal Level

Under the Canada Elections Act, EDAs are required to disclose to Elections Canada only the names of people who entered the nomination contests.[188] The only gender-related data Elections Canada receives — and shares with the House of Commons — are on candidates in general elections.[189] Similar data are not collected consistently at the provincial or territorial levels and across municipalities.[190]

A representative from Elections Canada explained that issues of privacy can arise if collecting certain information is not prescribed by law, including gender-related information.[191] Following a nomination contest, the EDA holding the contest files a report with Elections Canada which includes the names of each contestant and identifies the winners. The form used for this report does not include any gender questions. A representative from Elections Canada speculated that using information from the reports filed by EDAs to collect and analyze gender data in nomination contests would not be precise, as this process would require assigning genders to participants based on their names alone.[192]

The Committee was told that collecting data related to the number of women running for nominations would not be possible with any of Statistics Canada’s current survey vehicles.[193]

Both Jeanette Ashe and Jane Hilderman proposed two data-related strategies to increase the transparency of the nomination process at the federal level:[194]

- Elections Canada could be given a formal role in monitoring recruitment processes and candidate selection contests with respect to data collection; and

- parties could be required to report to Parliament on their nomination processes, including on the amount of notice given before membership deadlines close, on who stands for selection, and on who is successful and who is not.

More specifically, Jeanette Ashe recommended that section 476.1(1) of the Canada Elections Act be amended — if possible through Bill C-76, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and other Acts and to make certain consequential amendments — to require the collection of intersectional data from all participants in a selection contest, including, but not limited to: sex; gender identity; race; indigeneity; physical ability; and sexual orientation.[195] As well, Melanee Thomas proposed that EDAs be required to disclose and report information on selection and nomination processes to Parliament.[196]

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada consider making changes to allow, with candidates’ permission, the collection of intersectional data on candidates in nomination races, including data on gender identity.

B. The Federal Electoral System

The Committee heard about the role that the federal electoral system in Canada plays in women’s representation in politics. A few witnesses indicated that some kind of electoral reform — such as multi-member ridings instead of single-member ridings[197] — may be necessary to increase the diversity of elected representatives.[198] However, Louise Carbert told the Committee that it is social democracy, rather than electoral systems, that allows for the election of women.[199]

While Thérèse Mailloux argued that the first-past-the-post voting system is not a barrier to gender parity in Canadian politics,[200] several witnesses expressed the opposite.[201] Adopting a proportional representation (PR) system was cited by some witnesses as a potential solution to the purported barriers created by the current electoral system.[202] Witnesses recognized that while research has found that the representation of women in countries with PR systems is on average 8% higher than countries with other systems in 2012, PR systems do not guarantee parity.[203] Some witnesses speculated that PR systems may work well in combination with other proactive strategies.[204]

In a submitted brief, the Réseau des tables régionales de groupes de femmes du Québec recommended introducing a new electoral system that would assign “at least 40% of the seats in Parliament in proportion to the number of votes received by the parties across Canada” and that would “establish a national list.” National lists would “alternate between female and male candidates, starting with a woman, while ensuring a minimum representation of all the regions in Canada.” In this system, every voter could cast two ballots.[205]

C. The Impact of Incumbency on Candidates’ Success

The Committee heard that incumbent candidates are rarely challenged when seeking re‑nomination,[206] and that incumbent candidates tend to receive greater financial resources, support and visibility during an election campaign compared to non-incumbent candidates.[207] According to a representative from the Privy Council Office, “there is an incumbency advantage, and that generally seems to support men.”[208] Melanee Thomas indicated that her research has found that female incumbents are more “precariously placed” than their male counterparts.[209] However, Karen Sorensen explained that once women “prove [them]selves” they may be re‑elected.[210]

Approximately two-thirds of the current members of the House of Commons won their seats in ridings that did not have incumbent candidates.[211]

D. The Choice of Riding and Candidates’ Success

Witnesses told the Committee that women are often recruited for and nominated in ridings in which they are less likely to win based on their party’s past election results in the riding. Parties may present many female candidates but based on the ridings in which they run, these women have little chance of being elected.[212] The Honourable Deborah Grey told the Committee:

Don't put them, as women, in some riding they don't have a hope of winning. That's pathetic to me, when they say, “Look at all the women we ran.” They didn't have a hope of getting elected, but we put them on there and we look virtuous. No. Put capable women in from all backgrounds, and then we're able to share and make this country a much better place.[213]

Running in ridings in which their party is historically less likely to win can be a barrier to women becoming candidates, and also to women being elected.[214] In a submitted brief, the Groupe Femmes, Politique et Démocratie indicated that women have as much chance of being elected as their male counterparts if they run in ridings in which their party is historically more likely to win.[215] Brenda O’Neill added that election results are sometimes unexpected and can lead to a jump in women’s representation; parties may win ridings they did not expect to win, and women are often the candidates in such ridings.[216]

E. Expenditures for Nomination and Election Campaigns

The Committee was told that financing a nomination and/or an election campaign may be a greater barrier to electoral politics for women than for men;[217] according to Jenelle Saskiw, male candidates raise more money than women, and men donate more money to male candidates.[218] Furthermore, funding the early stages of a campaign can be very important, and this may be more difficult for women, particularly for racialized and Indigenous women, in part because of the gender wage gap.[219] Kayleigh Erickson suggested that initiatives to address the gender wage gap, or policies to safeguard candidates’ income, such as paying employees two months of full wages and benefits if they are nominated by any party as a candidate, may encourage more women to run for office.[220]

In a submitted brief, the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women and Women Transforming Cities expressed that women’s expenditures on campaigns tend to be approximately 10% higher than men’s expenditures. Women’s increased campaign expenditures may be linked to childcare and other care-related[221] or household responsibilities; “overcome[ing] … negative perceptions about women;” and strategies to be competitive against incumbent — often male — candidates.[222]

A representative from Elections Canada said that, at the federal level, certain provisions in the Canada Elections Act regarding spending limits for nomination contestants, candidates and parties “create equal opportunity for all participants by limiting the amount of funding that is required to compete in a nomination contest or election.” Personal expenses — including child care, or care for a person with a mental or a physical disability — incurred as a result of an individual’s candidacy are regulated under the Canada Elections Act. A candidate can contribute a maximum of $5,000 for personal expenses if they are not reimbursed from funds raised for the campaign. These requirements may lead to a disadvantage for candidates with care-related personal expenses. As such, the former chief electoral officer recommended that Parliament remove the restriction on personal expense contributions.[223]

Representatives from Elections Canada and from the Privy Council Office spoke to the Committee about the changes to the Canada Elections Act that were proposed in Bill C‑76, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and other Acts and to make certain consequential amendments,[224] in particular, provisions that would:[225]

- remove the limit on federal elections candidates’ own contributions towards personal expenses incurred as a result of their candidacy; Bill C-76 would allow candidates to pay these expenses with either campaign funds, or with their own funds. As such, candidates’ care-related costs would no longer contribute to their campaign expense limit.

- increase the reimbursement by the Receiver General of care expenses for federal elections candidates who receive 10% of the vote from the current 60% to 90%.

A representative from the Privy Council Office indicated that while the changes proposed in Bill C-76 would benefit all federal elections candidates, “evidence suggests this would be more likely to benefit women candidates.”[226] As mentioned in a previous section of this report, the Committee heard that the presence of a young child has a notable impact on women’s work hours[227] and that the cost of childcare was a barrier to women’s participation in electoral politics.[228] Furthermore, Bill C‑76 contains several provisions that would reduce barriers to participation for people with disabilities.[229]

WOMEN WORKING AS ELECTED OFFICIALS

Women working as elected officials in municipal or local governments, in provincial or territorial legislatures and in the House of Commons may face a number of barriers to achieve full and equal participation. For instance, according to a Samara Centre for Democracy survey, former female Members of Parliament indicated they felt they had to "work harder, prepare more, and speak" louder to be heard during their time in politics. Younger female respondents to the survey indicated that they "felt their credibility and their authority as a candidate and as [a Member of Parliament] were often more open to doubt" and that "their opinions did not carry as much weight" as their male counterparts.[230]

The sections that follow describe some of the barriers faced by female elected officials, such as a lack of family-friendly and gender-sensitive political workplaces, gender-biased media treatment and gender-based violence and harassment, as well as some possible solutions to address these barriers.

A. Family-Friendly and Gender-Sensitive Political Workplaces

The Committee heard that legislatures and other similar bodies were created and designed at a time when men and women did not play both professional and personal roles, as it is the case today.[231] As explained previously, politics is often seen as a masculine environment and the emphasis on debate and conflict can discourage women from pursuing a career in electoral politics. Indeed, the Committee heard that some women do not see themselves working in this type of environment.[232]

Witnesses shared with the Committee some family-friendly and gender-sensitive initiatives, such as parental leave, support for care work and work-life balance, as well as some changes to rules, procedures and practices, that could have a positive effect on female elected representatives if implemented in parliaments, legislatures or local governments.

1. Parental Leave

At the federal level, rules allow Members of Parliament to be away from the House of Commons for a maximum period of 21 days for sickness or other exceptional circumstances, but do not specifically address parental leave.[233] Sarah Childs told the Committee that implementing parental leave for parliamentarians would show “that Parliament is a place for people who have families.”[234]

A representative from the Privy Council Office explained that Bill C-74, An Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on February 27, 2018 and other measures aims to amend the Parliament of Canada Act “to allow Parliament to create a regime for maternity and parental leave.”[235] Bill C-74 received Royal Assent in June 2018. Section 59.1 of the Parliament of Canada Act was amended to allow for the Senate and the House of Commons to make regulations “that relate to the attendance of members, or to the deductions to be made from sessional allowances, in respect of its own members who are unable to attend a sitting of that House by reason of (a) being pregnant; or (b) caring for a new-born or newly-adopted child of the member or for a child placed with the member for the purpose of adoption.”[236] As of 5 December 2018, the House of Commons has not made such regulations.

The Honourable Eleni Bakopanos recommended introducing a 60-day leave period for female Members of Parliament who become parents to give them a “little more leeway to enjoy the first few months of their newborn's life.”[237]

2. Childcare

Lack of access to adequate childcare options is one of the barriers faced by female elected officials, as well as by women aspiring to a public charge.[238] Several witnesses stressed the importance of providing adequate childcare options to elected officials, particularly for female elected officials,[239] because the “lack of accommodation for caregiving in many political spaces can … limit women’s opportunities.”[240] Jenelle Saskiw shared some of the childcare-related challenges of elected officials in rural areas:

When I was first elected as mayor, I was paid $50 as a per diem for every meeting I attended. With a babysitter for four kids, I went in the hole. For two years, until I convinced council to allow us to raise the rates to $100 per diem, I actually lost money on every single meeting that I attended … I think it's really important to ensure that we look at everything as a well-rounded balance, to see where we can offer extra services, especially in rural communities. We don't have a day care. You rely on the girl down the street. You hope that she's free so that she can come and watch the kids for you in the evening, but it could be that she has an exam the next day and has to be back home by nine o'clock. I think that we have to look at how we can ensure that we have these resources in place that are fully rounded for absolutely everybody, regardless of where we are geographically and what age our children are.[241]

In a submitted brief, Equal Voice recommended the expansion of childcare service on Parliament Hill to full- and part-time care and to after-hours care so that services offered would better align with the parliamentary schedule.[242]

The Committee also heard that having a workplace, a schedule and policies that accommodate elected officials with caregiving responsibilities is important to ensure that parliaments and similar bodies are suitable workplaces for all.[243] The Committee was told that the Board of Internal Economy of the House of Commons has recently made changes to the travel point system for Members of Parliament. No travel point is deducted for dependents under the age of six and half a point per trip is deducted for children between the ages of 6 and 20 years of age and for youth between 21 and 25 years of age if they are full‑time students.[244]

3. Work-Life Balance for Elected Officials

Witnesses indicated that some women identify the difficulty of achieving a satisfactory work-life balance as a barrier to entering politics.[245] Witnesses shared a number of initiatives that could be undertaken to help achieve this balance.

Firstly, witnesses spoke about some flexible work arrangements that could be implemented to allow elected officials to respond to their various personal and family responsibilities, such as caring for family members. For instance, Nancy Peckford recommended that, during sitting weeks in the House of Commons, Fridays could be designated as constituency days for Members of Parliament so that they could work from their ridings.[246] As well, the Honourable Eleni Bakopanos recommended allowing pregnant Members of Parliament or new mothers to participate virtually in the work of the House of Commons. For example, travel requirements could be reduced for new mothers by allowing them to participate in Committee meetings and vote via teleconference or videoconference.[247] Marjolaine Gilbert recommended implementing a plan to foster greater work-life balance among politicians in legislatures and similar bodies, which would include day care, homework help, the ability to do telework and a review of wages.[248]

Secondly, witnesses told the Committee that having an efficient and predictable schedule can help elected officials achieve a better work-life balance.[249] For instance, Karen Sorensen explained that setting rules to make schedules of elected officials predictable would allow them to go home around the same time each day.[250] As well, a number of witnesses recommended adhering to fixed elections date.[251]

4. Rules, Procedures and Practices

A representative of the Samara Centre for Democracy suggested that female elected officials experience politics differently than their male counterparts, in part because of various rules, procedures and practices in politics.[252]

The Committee was told that one of the differences in how men and women experience politics can be seen in how each group experiences heckling. Jane Hilderman explained that, according to a survey of sitting Members of Parliament, “67% of women [Members of Parliament] reported gendered heckling versus just 20% of their male counterparts.”[253] Female respondents to the survey indicated that gender-based heckling affected their performance and reduced their willingness to participate in debates.[254] Witnesses suggested implementing preventive or disciplinary sanctions in legislatures or similar bodies to prevent the use of gender-based heckling, such as training, using camera angles that show hecklers, or having the Speaker of the House of Commons ask hecklers to remove themselves for a period of time and to apologize.[255] Actions such as shifting the language used to talk about women in politics, not objectifying women and not making gender-based comments, could help create a more inclusive environment.[256]

Witnesses shared various examples of changes that could be made to ensure that parliaments, legislatures and local and municipal councils are gender-sensitive. Parliamentary roles and duties could be distributed more equally between men and women to ensure that women have a chance to influence parliamentary rules, procedures and practices.[257] In this regard, Dawn Wilson suggested implementing policies that support “increased gender and diversity.”[258]

Secondly, witnesses stressed the importance for parliaments and similar bodies to subjects themselves to gender-sensitive parliament audits, or gender safety audits, with the goal of identifying areas in which they might not be sufficiently sensitive to the needs of women or of elected officials from diverse identity groups.[259] In a submitted brief, the Groupe Femmes, Politique et Démocratie suggested creating a structure whose mandate would be “to diagnose gender sensitivity and establish an action plan to prioritize parity” within legislatives assemblies.[260]

Furthermore, witnesses told the Committee that elected officials’ remuneration should be competitive. Nancy Peckford told the Committee that Members of Parliament’s office budgets should be increased to ensure adequate resources are available for constituency offices. As well, Ms. Peckford added that Members of Parliament’s remuneration should be competitive so that all qualified women can run for elected office at the federal level if they wish.[261]

Finally, to “address the inequality that allow women’s vulnerability to be exploited,” the National Democratic Institute recommended, in a submitted brief, that political parties implement measures to strengthen internal dispute resolution mechanisms; enforce sanctions for perpetrators of violence; increase transparency of resources allocation to candidates; review parties’ meeting times and locations; and allow for monitoring of parties’ social media accounts for abusive or hateful communications.[262]

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada request that the Minister for Women and Gender Equality, at the next meeting of Canada’s Federal-Provincial-Territorial Status of Women Forum, urge all jurisdictions to discuss ways to make legislatures more gender-diverse.