FINA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INCOME INEQUALITY IN CANADA: AN OVERVIEWCHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTIONOn 13 June 2012, Private Members’ Business M-315

passed in the House of Commons by a vote of 161 to 138. The motion instructed

the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance to undertake a study on

income inequality in Canada. (i) a review of Canada’s federal and provincial systems of personal income taxation and income supports, (ii) an examination of best practices that reduce income inequality and improve GDP per capita, (iii) the identification of any significant gaps in the federal system of taxation and income support that contribute to income inequality, as well as any significant disincentives to paid work in the formal economy that may exist as part of a “welfare trap,” (iv) recommendations on how best to improve the equality of opportunity and prosperity for all Canadians; and that the Committee report its findings to the House within one year of the adoption of this motion. To that end, over the course of three hearings and in written submissions, the Committee received the views of academics, think tanks, associations, individuals and others about a range of issues related to income inequality in Canada. While views about such topics as poverty — which may, but need not necessarily, exist alongside income inequality, as it is possible to have a highly unequal distribution of income but no poverty as long as the person at the bottom of the income distribution has an adequate income — were also presented, the Committee decided to focus largely on the views related to the topics described in M-315 and to topics that have not recently been examined by other parliamentary committees. Consequently, issues related to poverty in Canada generally, and the standard of living for low-income seniors in particular, are not examined in this report, as they were recently reported on by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities in Federal Poverty Reduction Plan: Working in Partnership towards Reducing Poverty in Canada, by the Special Senate Committee on Aging in Canada’s Aging Population: Seizing the Opportunity, and by the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology in In From the Margins: A Call to Action on Poverty, Housing and Homelessness. Chapter Two of this report focuses on the measurement of income inequality and economic disparity in Canada, while Chapter Three comments on potential explanations of income inequality in Canada. The focus of Chapter Four is possible implications of income inequality in Canada, while the witnesses’ proposals designed to reduce income inequality and its impacts are presented in Chapter Five. The report concludes with the Committee’s recommendations, which are contained in Chapter Six. CHAPTER TWO: MEASUREMENT OF INCOME INEQUALITY AND ECONOMIC DISPARITY IN CANADAIncome inequality can be measured in a variety of ways, ranging from relatively basic concepts — such as deciles, quintiles, and changes in the distribution of incomes — to more sophisticated techniques — such as through a Lorenz curve or a Gini coefficient. Of these measures, most of the Committee’s witnesses focused on the Gini coefficient. That said, economic disparity among individuals can be assessed on the basis of consumption and wealth inequality, the extent to which income mobility occurs, and the proportion of the population that has low income or lives in poverty; the witnesses also spoke about a number of these issues, as noted below. A. BackgroundAccording to Statistics Canada estimates, in 2010, the top 1% of income earners in Canada comprised about 254,700 individuals, and they reported a median income of $283,400. According to the Conference Board of Canada, income inequality has grown over time; the top 1% of income earners in Canada has accounted for almost 33% of all growth in median incomes since the late 1990s, an increase from 8% during the 1950s and 1960s. The distribution of incomes ranked from lowest to highest can be grouped in various ways, such as by quintile — that is, each 20% share of incomes in the population — or by decile — that is, each 10% share of incomes in the population. Using 2010 constant dollars, Table 1 presents the level and change in average market income and average after-tax-and-transfer — or disposable — income in Canada over time, by income quintile. From 1976 to 2010, while the top 20% of Canadian income earners — the highest quintile — had their average market income rise by 28.9%, the bottom 20% of income earners — the lowest quintile — had their average market income fall by 22.5%. When disposable income is considered, the disparity between the lowest and highest income quintiles was reduced from 1976 to 2010. Disposable income grew for each income quintile from 1976 to 2010, but the growth was especially notable for those with the lowest and highest incomes, increasing by 15.9% and 27.1% respectively. Table 1 — Level and Change in Average

Market Income

Notes: “Market income” includes employment earnings, net investment income, retirement income and other forms of income. “After-tax-and-transfer income” — or disposable income — adds government transfers (e.g., government payments for income maintenance and social assistance) to, and subtracts federal and provincial income taxes from, market income. “All family units” includes economic families and unattached individuals. An economic family is defined as a group of two or more persons who live in the same dwelling and are related to each other by blood, marriage, common law or adoption. An unattached individual is a person living either alone or with others to whom he/she is unrelated, such as roommates or a lodger. Source: Table prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, CANSIM, Table 202-0701, “Market, total and after-tax income, by economic family type and income quintiles, 2010 constant dollars,” accessed April 2013. As can be calculated from Table 1, the difference between average disposable income in the lowest income quintile and that in the highest income quintile grew from $94,000 in 1976 to $120,900 in 2010. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Canada ranked 21st among 34 industrialized countries in terms of income inequality in the late 2000s, as measured by the gap between the top 10% of income earners and the rest of the population. Canada’s ratio of 4.2, which indicates that the income for the top 10% of income earners is about four times higher than the income for the remaining 90% of income earners, was about the same as the OECD average at that time. A Lorenz curve is constructed by comparing cumulative shares of the population, ranked from the lowest to the highest income levels, to cumulative shares of income that this population receives. Figure 1 shows a theoretical representation of Lorenz curves for Country A, which shows relatively lower inequality, and Country B, which shows relatively greater inequality. As shown in Figure 1, income inequality is greater in one country than in another country when its Lorenz curve is closer to the line of absolute inequality. Figure 1 — Theoretical Lorenz Curves for Country A and Country B

Source: Joseph L. Gastwirth, “A General Definition of the Lorenz Curve,” Econometrica, Vol. 39, No. 6 (Nov., 1971). A country’s Gini coefficient can be calculated as the area between its Lorenz curve and the line of perfect equality. A Gini coefficient of 1 indicates maximum inequality, as a single person in a society has all of the income and the remainder of the population has none; a Gini coefficient of 0 indicates maximum equality, as everyone has exactly the same income. In reality, Gini coefficients range from 0 to 1. In 2010, using the Gini coefficient for disposable income to measure income inequality, Canada ranked fourth among the Group of Seven countries, after Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States, as shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 — Income Inequality as Measured by the Gini Coefficient for Disposable Income, Total Population, Group of Seven Countries, 2010

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development, “Income Distribution — Inequality,” OECD Social and Welfare Statistics. Using disposable income for the population aged 18 to 65 years, Gini coefficients for Canada and selected OECD countries in the mid-1980s and the late-2000s are illustrated in Figure 3. Figure 3 — Income Inequality as Measured

by the Gini Coefficient

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development, “Income Distribution — Inequality,” OECD.StatExtracts. Figure 3 shows that — in the late 2000s — the Gini coefficient for Canada, at 0.324, was higher than the average for OECD countries, at 0.311. At that time, Mexico’s Gini coefficient of 0.476 indicated that income inequality was higher in that country than in Canada; on the other hand, the Nordic countries’ Gini coefficient of about 0.25 shows that income inequality was lower in those countries than in Canada. From the mid-1980s to the late 2000s, the Gini coefficient increased in Canada, as it did in a number of other countries. While income inequality is one measure of economic disparity among individuals, studies by Jason Clemens at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, Yanick Labrie at the Montreal Economic Institute and Chris Sarlo at the Fraser Institute argue that inequality should be measured by instead considering the ability to purchase goods and services, or “consumption” inequality. From that perspective, “consumption” may be a relatively more accurate indicator of inequality, as it measures the ability to maintain an adequate standard of living. According to the aforementioned studies, disparities in consumption spending are lower than are disparities in income, and have remained relatively constant over the last 35 years. Furthermore, these studies note that relatively low and stable disparities in consumption over the lifetime of an individual can be facilitated through loans and savings, as people tend to finance consumption by borrowing when young and by accessing savings when old. As well, Mr. Clemens’ study for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute questions the reliability of reported incomes, which in some cases may exclude revenues obtained through both legal (e.g., under-reporting of government assistance) and illegal (e.g., the underground economy) activities. Another form of economic disparity among individuals is asset inequality. As shown in Figure 4, the median amount of assets — net of debt — held by the highest quintile increased by 28% from 1999 to 2005, while the median amount of assets — net of debt — held by the lowest quintile decreased by 13% over the period. Figure 4 — Median Net Worth, by Net Worth Quintile, Canada, 1999 and 2005 (constant 2005 dollars)

Note: Net worth is equal to assets minus debt. Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Assets and debts held by family units, median amounts, by net worth quintile”, Survey of Financial Security. Gini coefficients reflect a given point in time, and do not provide an indication of whether gaps in income between the highest and lowest income earners have changed over time. Studies by Mr. Labrie for the Montreal Economic Institute, by Zanny Minton Beddoes for The Economist and by Miles Corak, Lori Curtis and Shelley Phipps released by Dalhousie University have noted that income inequality can arise for positive reasons (e.g., reward for productive work) and for negative reasons (e.g., children from poorer families may be excluded from equal access to opportunity). Furthermore, these studies note that income inequality at a point in time is not necessarily an issue if there is a general trend towards reduced lifetime inequality as a person ages from childhood to adulthood — intragenerational income mobility — or if a child grows up and has an income that exceeds that of his/her parent(s) — intergenerational income mobility. According to former Queen’s University professor Charles Beach, writing in Dimensions of Inequality in Canada, “[i]f all workers systematically progress along a given age-earnings trajectory over their careers, there is less social concern about any degree of earnings inequality in the economy. But if workers are largely stratified within lower, middle, and upper regions of the distribution throughout their careers, the degree of earnings inequality carries a much greater degree of social concern.” In a background paper prepared for Canada 2020, Mr. Corak suggests that perceptions about the significance of inequality depend on the degree of income mobility, and particularly intergenerational income mobility. He notes that high income inequality that persists from one generation to the next “may lead to lower levels of efficiency and productivity and the society may well be considered less fair if access to jobs is determined more by inherited advantage than by individual talent and energy.” Figure 5, which illustrates intergenerational income mobility for selected OECD countries, suggests that Canadian children raised during the period under study displayed a relatively high degree of intergenerational income mobility; the children in Nordic countries showed relatively greater intergenerational income mobility. Figure 5 — Intergenerational Income Mobility, Gini Coefficient of Disposable Household Income, Selected Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Countries

Note: The figure considers the income mobility of individuals who were children in 1985 and who were adults in the late 2000s. Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Miles Corak, Understanding inequality and what to do about it, University of Ottawa, Presentation to the All-Party Anti-Poverty Caucus, House of Commons, Ottawa, 12 February 2013. The aforementioned study by Mr. Corak, Ms. Curtis and Ms. Phipps released by Dalhousie University, and another study by Mr. Corak for The Pew Charitable Trusts, compared intergenerational income mobility in Canada and the United States, and found that Canada’s intergenerational income mobility was up to three times greater than in the United States. While residents of both countries are thought to place a high value on income mobility and individual effort, differences in the role of families, labour markets and public policies may explain the relatively greater degree of intergenerational income mobility in Canada. In particular, according to the former study, public policies in Canada compensate for inequalities in family background and the labour market to a greater extent than they do in the United States. In examining the relationship between family economic background and the income attainment of children from poorer families as they become adults, four major policy differences between Canada and the United States that facilitate income mobility were identified:

In addition to identifying low income earners by their income quintile, Statistics Canada also produces two relative measures of low income — the low income cut-off (LICO) and the low income measure (LIM), which compare household income to a standard level of income — and an absolute measure of low income — the market basket measure (MBM), which estimates the minimum level of income needed for survival:

The Conference Board of Canada has noted that developed countries, such as Canada, frequently refer to relative measures — such as the LICO and the LIM — that compare income for a household to some standard level of income. Absolute measures, such as the MBM, estimate the minimum income needed for survival. As shown in Table 2, the share of the population in low income varies depending on the measure of low income, both in a given year and over time. Table 2 — Percentage of the Population

Aged 18—64 Years

Notes: “n.a.” means not available. Low income cut-off, after tax, is determined from an analysis of Statistics Canada’s 1992 Family Expenditure Survey data. The income limits used to derive estimates in this table are selected on the basis that families with incomes below these limits usually spent 63.6% or more of their income on food, shelter and clothing. Low income cut-offs are differentiated by community size of residence and family size. The low income rates shown in the table are overall averages. Low income measure, after tax, is a relative measure of low income, set at 50% of adjusted median household income. These measures are categorized according to the number of persons present in the household, reflecting the economies of scale inherent in household size. The low income rates shown in the table are overall averages. Market basket measure represents the cost of a basket that includes: a nutritious diet, clothing and footwear, shelter, transportation, and other necessary goods and services (such as personal care items or household supplies). The cost of the basket is compared to disposable income for each family to determine low income rates. The low income rates shown in the table are overall averages. Source: Table prepared using data from Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 202-0802, “Persons in Low Income Families,” accessed April 2013. Moreover, as shown in Figure 6, the proportion of the Canadian population in low income varies by age group and has generally been falling for each age group in recent years. A number of federal tax and transfer measures may have contributed to declines in the proportions of children, some households and seniors living in low income, including the CCTB, the National Child Benefit Supplement (NCBS), the Goods and Services Tax/Harmonized Sales Tax Credit, the Working Income Tax Benefit (WTIB), the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) and the Allowance for the Survivor. Figure 6 — Percentage of the Population in Low Income, by Age Group, Canada, 1976—2011 (%)

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, Table 202-0802, “Persons in low income families,” accessed 18 October 2013. B. Witness ViewsStephen R. Richardson, an Executive Fellow at the University of Calgary who appeared as an individual, told the Committee that a Gini coefficient measures the extent to which the distribution of a variable — such as income — deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. Figure 7 was submitted to the Committee by the University of Toronto’s Alan Walks, who provided his views as an individual. According to the figure, after-tax-and-transfer — or disposable — income inequality in Canada, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increased over time. In particular, it rose from about 0.36 in 1990 to almost 0.40 in 2010. Figure 7 — Level of Income Inequality as Measured by the Gini Coefficient, Before-Tax and After-Tax Family Income of all Family Types, Canada, 1976—2010

Source: Figure provided to the House of Commons Standing Committee by Alan Walks, University of Toronto, 5 April 2013. In providing information about Canada’s Gini coefficient in an

international context, J.

David Hulchanski and Robert A. Murdie — professors at the University of

Toronto and York University respectively who provided their views as

individuals — compared the degree of income inequality in Canada to that in

other developed countries. As shown in Figure 8, as of the late 2000s, Canada

ranked 5th among 15 relatively wealthy western nations in terms of

income inequality, after New Zealand, Australia, the United Kingdom and the United

States. The Canadian

Centre for Policy Alternatives and Figure 8 — Gini Coefficient for Fifteen Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Countries, late 2000s

Note: Gini coefficients are rounded to the nearest 0.01. Source: Adapted from a figure provided to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance by J. David Hulchanski, University of Toronto, and Robert A. Murdie, York University, 5 April 2013. According to Canada

2020, the TD

Bank Financial Group and Bradley

A. Corbett, a professor at Western University who — along with several

colleagues — provided his views as an individual, the Gini coefficient is

limited in its ability to identify changes at the lower and upper ends of the

income distribution. In particular, Mr.

Corbett referenced an OECD study indicating that, for developed countries,

the incomes of people at the upper end of the income distribution are growing

faster than the incomes of those at the Michael R. Veall, a professor at McMaster University who appeared as an individual, spoke to the Committee about how economic gains have disproportionately gone to persons at the top end of the income distribution. According to him, the disposable income of the top 1% of income earners increased by 77% from 1986 to 2012, the disposable income of the top 0.1% grew by 131%, and the disposable income of the top 0.01% rose by 160%. Over the 1986 to 2012 period, the disposable income of the bottom 90% of income earners grew by 19%. The Canadian Taxpayers Federation suggested that the increase in income of the top 1% of income earners, representing about 254,000 people, had been occurring at the same time that these earners had been increasing their share of total income taxes paid by Canadians. Citing a report by Statistics Canada, it noted that — in 1982 — the top 1% of income earners paid 13.4% of all federal and provincial income taxes, a proportion that grew to 23.3% in 2007. The Montreal Economic Institute and Mr. Clemens, Executive Vice-President of the Fraser Institute who appeared as an individual, argued that “consumption” is a relatively more accurate indicator of inequality, as it measures the ability to maintain an adequate standard of living. As well, the Montreal Economic Institute stated that consumption inequality in Canada has been less than income inequality over the past 30 years, and has changed very little over that period. It also said that although seniors tend to have lower incomes than those in the working-age population, they have a relatively lower degree of consumption inequality, since they have had an opportunity to accumulate assets and may have limited debt, which allows them to maintain an adequate standard of living. According to the TD

Bank Financial Group and the C.D.

Howe Institute, wealth inequality — which results from differences in the

ability to accumulate assets over time — is also an important part of economic

disparity in Canada. According to Social

and Enterprise Development Innovations and Mr.

Walks, asset inequality — which began growing in Canada in 1977 — now

exceeds income inequality to a significant extent, and continues to grow as a

result of changes in wealth at both ends of the income distribution. As

explained by Jennifer

Robson, a lecturer at Carleton University who provided her views as an individual,

those with higher incomes tend to have more assets, and they tend to hold their

assets in a range of preferential tax instruments that increase those assets’ According to the Fraser Institute, the Montreal Economic Institute and Mr. Veall, income inequality at a particular point in time — as measured by the Gini coefficient — is not necessarily a problem if there is a general trend towards reduced lifetime inequality. Mr. Veall, Campaign 2000 and the Montreal Economic Institute referenced various studies of intergenerational economic mobility. According to them, studies that compare economic mobility in Canada with economic mobility in the United States find that while residents of both countries are thought to place a high value on economic mobility and individual effort, differences in the role of families, labour markets and public policies related to health care, child care and schooling may explain the relatively greater degree of intergenerational economic mobility in Canada. Mr. Corak, a professor at the University of Ottawa who provided his views as an individual, highlighted that a significant portion of the Canadian population remains in low income across generations. In particular, he noted that while intergenerational economic mobility may be higher in Canada than in some other countries, about a third of low-income Canadian children become low-income adults. As well, the Conference Board of Canada told the Committee that economic mobility does not remove all of the other negative impacts of higher inequality; including the negative impacts that inequality has on economic growth and the ability of individuals to use their skills. Although the Committee’s study was focused on income inequality rather than on poverty, a number of the Committee’s witnesses — such as the TD Bank Financial Group, Campaign 2000, the Canadian Nurses Association, the Canadian Union of Public Employees, Women’s Centres Connect, the Broadbent Institute, Ronald Labonté, Arne Ruckert and Sam Caldbick, researchers at the University of Ottawa who provided their views as individuals, and Diana Gibson and Lori Sigurdson, researchers at the University of Alberta and Alberta College of Social Workers respectively who provided their views as individuals — suggested that the incidence of poverty is positively related to the degree of income inequality in a country. From another perspective, the Montreal Economic Institute noted that an increase in income inequality can occur at the same time as poverty rates decrease. it stated that — from 1995 to 2010, a period that it characterized as largely involving an increase in income inequality and a reduction in government measures designed to redistribute income — the average disposable incomes of the lowest income earners increased by 25% while the number of persons living below the “poverty line” decreased by more than 60%. Campaign 2000, Citizens for Public Justice and the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction shared their view that there is no commonly agreed threshold for the level of income below which a Canadian is considered to be “in poverty.” That said, the Committee’s witnesses cited a number of measures of low income. Some witnesses — such as the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Conference Board of Canada — spoke about the general trend of increasing low-income rates as shown by the LIM, which measures incomes that are below half the median family income, with adjustments for family size. The Montreal Economic Institute and the TD Bank Financial Group mentioned the declining low-income rates observed since the mid-1990s when measured by the LICO, which is the threshold at which a family of a given size living in a community with a certain population spends a specified percentage more of its income on food, clothing and shelter than does the average family. Beverley Smith, who provided her views as an individual, proposed that — regardless of the measure used — poverty, particularly among children, is continuing to exist; in her view, poverty limits the ability of every child to have enough financial support to “thrive” and be “financially secure.” Mr. Clemens noted that three main groups tend to remain in low income over time: single parents, those who fail to complete high school, and those for whom drug and alcohol use are a problem. The Conference Board of Canada stated that low-income rates for the elderly have fallen from the levels in the 1970s, and that Canada now has one of the lowest low-income rates for seniors in the world; that said, low income among the elderly has increased somewhat in recent years. CHAPTER THREE: POSSIBLE REASONS FOR INCOME INEQUALITY IN CANADAThe nature and extent of income inequality in Canada — and changes in them over time — can be explained in a variety of ways. For example, market and institutional forces may play a role, as may the demographic changes occurring in Canada. A variety of these forces and changes were described by the Committee’s witnesses. A. BackgroundStudies by Dalhousie University’s Lars Osberg and the OECD identify market forces as the main factor affecting income inequality in Canada and around the world. For example, globalization and technological progress are widening the disparity in employment earnings between those who earn very high incomes and those who earn very low incomes. With the globalization of production, manufacturing jobs in Canada have been outsourced to countries with relatively lower average wage rates. At the same time, wage rates and employment levels have increased in Canada for workers in highly skilled occupations, especially in the information technology sector. Figure 9 shows average annual wages in selected countries, while Figures 10 and 11 indicate unemployment rates in Canada — including for youth, which remains high despite the country's economic recovery from the global financial and economic crisis — and in selected countries respectively.

Figure 9 – Average Annual Wages, Selected

Organisation for Economic

Note: Purchasing Power Parities represent the rates of currency conversion that equalize the purchasing power of different currencies by eliminating differences in price levels between countries. Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Average annual wages”, OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics.

Figure 10 — Unemployment Rate, by Age Group, Canada, 1976–2012 (%)

Source: Figure prepared using information obtained from: Statistics Canada, Table 282-0002, “Labour force survey estimates (LFS), by sex and detailed age group” accessed 8 November 2013. Figure 11 – Unemployment Rates for Youth and the Population, Selected Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Countries, 2012 (%)

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Unemployment rate % of labour force and Youth unemployment rate % of youth labour force. According to studies by the University

of British Columbia’s Nicole Fortin, Regarding tax and transfer systems in Canada, the aforementioned study by Ms. Fortin, Mr. Green, Mr. Lemieux, Mr. Milligan and Mr. Riddell, and that by the OECD, suggest that the federal and provincial/territorial tax systems have become less progressive through changes that have benefitted mainly higher-income earners, such as reduced marginal income tax rates for those earning the highest incomes, through the introduction of federal non-refundable tax credits, and through reductions in capital gains taxation. As well, Action Canada, the OECD and the Caledon Institute of Social Policy suggest that the effectiveness of the transfer system has been reduced through reductions in social assistance benefits and the introduction of stricter eligibility requirements for federal and provincial income maintenance programs, such as the Employment Insurance (EI) program. Regarding the impact of the tax system on those who earn lower incomes, although the federal government has introduced various tax policies to increase the disposable incomes of those with little or no labour market income, the Broadbent Institute, the National Council of Welfare, and the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities identify the need to enhance government policies that lessen the negative impacts of transitioning from social assistance to paid employment. These studies suggest that a “welfare wall” exists for those receiving social assistance benefits, such as social assistance payments, child care support and housing subsidies, which are “clawed back” if recipients earn employment income. More generally, the Broadbent Institute, the National Council of Welfare, and the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities note that further enhancements to the tax and transfer system are required to provide those who are most economically disadvantaged with more adequate and stable income, and to provide support during periods of financial difficulty. Appendix A contains information about selected elements of Canada’s tax and transfer system. The OECD, the Conference Board of Canada, and a study by Mr. Veall and the University of California at Berkeley’s Emmanuel Saez, indicate that — from 1976 to 1994 — Canada’s tax and transfer systems were relatively effective at reducing income inequality. However, these studies suggest that, since then, the redistributive impact of these systems has been relatively less effective at reducing income inequality in Canada; they also argue that there has been little change in this regard since the early 2000s. According to the Gini coefficient for Canada, as shown in Figure 12, disposable income inequality decreased during the 1980s, with the coefficient reaching a low of 0.281 in 1989. According to this measure, income inequality rose in the 1990s, and has remained at around 0.32 since the early 2000s.

Figure 12— Market Income and Disposable

Income Inequality, as Measured

Notes: To account for the economies of scale present in larger households, household incomes are expressed on a “per-adult-equivalent” basis. The grey bars within the figure represent the duration of major recessions in Canada, based on information from the C.D. Howe Institute, C.D. Howe Institute Business Cycle Council Issues Authoritative Dates for the 2008/2009 Recession. Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from

Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table Some studies argue that, in an effort to reduce the extent to which Canadians who earn a high income may move to a jurisdiction with lower personal taxes, or may seek ways to reduce their taxable income within their existing jurisdiction, marginal tax rates for the top income earners have not increased in Canada. According to the C.D. Howe Institute’s Alexandre Laurin, for the 2010 taxation year, a 1% increase in the marginal “net-of-tax” rate for high income earners resulted in a 0.7% reduction in the taxable income reported by these taxpayers. Other studies, such as the aforementioned study by Mr. Saez and Mr. Veall, suggest that the declines in the top marginal tax rates may also explain the observed increase in the share of total income for the highest income earners relative to lower income earners. In contrast to these views, which suggest that changes to the tax system are a main factor in increasing income inequality, other studies — including a study, authored by Simon Fraser University’s John Kesselman and then-University of British Columbia graduate student Ron Cheung, that appeared in Dimensions of Inequality in Canada — suggest that government transfers have a proportionately larger impact in raising the incomes of the lowest two income quintiles than do personal income taxes in reducing the net incomes of the highest two income quintiles. According to the Centre for the Study of Living Standards, over the last three decades, federal and provincial government transfers have accounted for about 70% of the reduction in income inequality as measured by the market income Gini coefficient, compared to about 30% for the tax system. B. Witness ViewsIn speaking about the demographic reasons for income inequality in Canada, a number of the Committee’s witnesses said that population aging, gender-related issues and challenges related to the labour market integration of disadvantaged groups have the potential to increase income inequality in the coming years. The Frontier Centre for Public Policy and Ms. Fortin, a professor at the University of British Columbia who appeared as an individual, said that although the young and poorly educated — who tend to be at the lower end of the income distribution — are more vulnerable to being excluded from full-time jobs with security and benefits, labour force attachment issues are arising for significant numbers of those in the middle of the occupational skill and wage distributions. According to the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, income inequality in Canada is expected to increase over time, and there is likely to be a growing gap between the labour force attachment of an aging workforce and younger workers. It expected that income inequality will increase as an aging population moves up the income distribution, since older workers tend to have more experience and skills, and thus relatively higher wages. Younger workers tend to be employed in more “precarious jobs,” which — as stated by Poverty and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario — are jobs lacking the security or benefits that exist in more traditional employment relationships. As noted by the Broadbent Institute, more than one third of working Canadians currently do not have permanent, full-time paid jobs. According to a number of the Committee’s witnesses — including the Council of Canadians with Disabilities, Women’s Centres Connect, Mr. Walks and the Assembly of First Nations — the rise in the number of “precarious jobs” has the potential to have a large impact on disadvantaged demographic groups, such as women, immigrants, Aboriginal peoples and persons with disabilities. The Council of Canadians with Disabilities and Women’s Centres Connect indicated that women are at greater risk of experiencing low income than are men, as women tend to be responsible for family care and are more likely to be lone parents with fewer opportunities for stable, high-paid employment. Regarding immigrants, Mr. Walks explained that the average incomes of recent immigrants have been declining over time, as recent immigrants tend to find lower-paid work and to work fewer hours. From the Aboriginal perspective, the Assembly of First Nations told the Committee that the incomes of Aboriginal peoples are generally 30% lower than the incomes of non-Aboriginal Canadians. It referenced a 2010 study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives that estimated that, at the current rate of change, it would take 63 years for the income gap between Aboriginal peoples and non-Aboriginal peoples to be closed. Ms.

Fortin noted that the “polarization” of male earnings in the United

States in the 1990s, according to which median male earnings did not increase

as much as male earnings at the ends of the income distribution, resembled the

experience in Canada in more recent years. Since the late 1990s, the real

hourly wage of median male income earners in Canada increased by about 5%, while

the wages of the highest male income earners increased by 12% and those of the

lowest male income earners rose by 9%. Other witnesses spoke about the role of market forces in increasing income inequality in Canada and around the world. According to some witnesses — includingMr. Corak, the TD Bank Financial Group, the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, Ms. Fortin and Edward J. Farkas, who provided his views as an individual — globalization and technological progress are widening the gap in employment earnings between very high income earners and very low income earners. According to them, with the globalization of production, manufacturing jobs in Canada have been outsourced to countries with relatively lower average wage rates. They noted that, at the same time, wage rates and employment levels have increased in Canada for workers in highly skilled occupations, especially in the information technology sector. In terms of the impacts of globalization and technological change

on Canada’s labour force, Mr.

Corak told the Committee that people who traditionally did routine tasks —

whether they were physical or cognitive — experienced a reduction in the value

of those skills, while the opposite was true for people who did non-routine

tasks. According to the TD Bank Financial Group, the combination of more people with university degrees and high-skill jobs, and the decreasing number of low-skill jobs in Canada, is likely to lead to increased income inequality. As well, the Frontier Centre for Public Policy noted that the rise in demand for highly skilled labour as a result of global market forces is likely to continue, leading to significant gains in income for those who earn high incomes. A number of the Committee’s witnesses —

including the Canadian

Union of Public Employees, Ms.

Fortin, the Institut

du Nouveau Monde and Mr.

Walks — identified institutional forces, such as declining

unionization rates, stagnating minimum wage rates and deregulation of the

workplace, as potential factors affecting income inequality. According to the Canadian

Union of Public Employees and the Broadbent

Institute, equality and unionization rates

are positively co-related; when unionization declines, income inequality is

increased and the share of income going to the top 1% of income Ms. Fortin noted that the unionization rate among male workers declined from 47% in 1980 to 25% in 2012. She also explained that declining unionization rates contribute to the polarization of male earnings, as the wage premium associated with unionization is highest at the lower end of the male wage distribution. Ms. Fortin also described the importance of minimum wages, especially for women and young workers, arguing that they alleviate rising wage inequality at the bottom of the income distribution. The Institut du Nouveau Monde said that wage polarization has occurred at the same time as declines in rates of unionization and increases in competition as a result of freer trade. From the perspective of industrial sectors, Mr. Walks informed the Committee that polarization has occurred as globalization leads to the relocation of manufacturing jobs, and as declining rates of unionization reduce the pay of middle-income workers.He observed that adequately compensated middle-income jobs are disappearing, with growth in either high-income jobs in business services, finance, sales and management, or in low-income service jobs that have little protection or few benefits. Some of the Committee’s witnesses spoke about the role played by workplace deregulation in increasing income inequality. As explained by Mr. Walks, deregulation and the reduction in the welfare state have removed a number of the protections for those who are unemployed, and have led low-income households to work longer hours for lower wages; at the same time, the incomes of senior executives have been rising. In relation to deregulation of the non-financial sector and executive compensation, Richard Wilkinson, Emeritus Professor at the University of Nottingham who appeared as an individual, highlighted that — for the top 300 U.S. companies — executives earned about 25 or 30 times as much as the average production worker in 1980; by the early 2000s, executives earned about 300 to 400 times as much. Similar remarks were made by the Institut du Nouveau Monde. CHAPTER FOUR: POTENTIAL IMPACTS OF INCOME INEQUALITY IN CANADAIncome inequality in a country can have a variety of impacts, including on economic growth, social integration, health, and cities, communities and neighbourhoods. The Committee’s witnesses spoke about a number of these impacts. A. BackgroundAccording to the Conference Board of Canada, “… high inequality can diminish economic growth if it means that the country is not fully using the skills and capabilities of all its citizens or if it undermines social cohesion, leading to increased social tensions. Second, high inequality raises a moral question about fairness and social justice.” Mark Cameron, writing for Canada 2020, has said that and “extreme income inequality, even where the least well-off are increasing their income levels, can undermine the sense of social cohesion needed for a democratic society”; similar comments have been made by Action Canada. As was shown in Table 1, and consistent with the conclusions reached by Action Canada, the Broadbent Institute, TD Economics, and Ms. Fortin, Mr. Green, Mr. Lemieux, Mr. Milligan and Mr. Riddell in their aforementioned study, a polarization — or “hollowing out” — of middle-income earners has occurred in Canada. This phenomenon has been found to exist in the United States as well, and is thought to be a threat to a sustainable economic recovery. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the OECD, the relationship between income inequality and economic growth is complex: although inequality can limit growth, some level of inequality is necessary to ensure that incentives exist for investment and growth. The IMF, the OECD and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives note that rising income inequality may reduce people’s borrowing opportunities and investments in human capital, both of which support the development of productive skills and entrepreneurial activity; the result of rising income inequality is reduced economic growth and potential, and a loss of long-run living standards. According to some studies, continued growth in income inequality could have negative consequences for social integration that would affect all of society. In a study by Deloitte and the Human Resources Professionals Association, the worst-case scenario — a continuation of current trends in income inequality — would, by 2025, lead to a further widening of income inequality between lower and higher income quintiles; moreover, the number of disenfranchised individuals — those unemployed or with insecure and low-paying jobs — would have grown to become a group larger in size than those employed in secure and high-paying jobs. The study also suggests that unemployment and underemployment, and reduced labour force participation, would have given rise to an “us versus them” attitude, marginalized groups would have become organized and vocal, and — increasingly — Canadians might engage in protests and general strikes. Similarly, in The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone, Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett — co-founders of the United Kingdom’s The Equality Trust — suggest that income inequality is something about which all citizens and governments should be concerned. They argue that the quality of life is worse for everyone in societies in which there are wide disparities between those at the top of the income distribution and those at the bottom. As well, according to them, “[t]he evidence shows that reducing inequality [as measured by income disparities] is the best way of improving the quality of the social environment, and so the real quality of life, for all of us.” Finally, in the view of Mr. Wilkinson and Ms. Pickett, income inequality is an indicator of the degree of “social hierarchy,” or the degree of connection among individuals within a society. They believe that social and health problems are more common at the bottom of the “social hierarchy” than at the top of the hierarchy, and are more common in more unequal societies. B. Witness ViewsSome of the Committee’s witnesses — such as the Conference Board of Canada, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Canadian Nurses Association — shared their view that a high degree of income inequality can impede economic growth. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Canadian Nurses Association referred to a 2011 IMF study, entitled Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin?. The study found that rising income inequality may reduce people’s borrowing opportunities and investments in human capital, both of which support the development of productive skills and entrepreneurial activity; the result of rising income inequality is reduced economic growth and economic potential and a reduction in long-run living standards. Similarly, Mr. Wilkinson indicated that most research on the link between income equality and economic growth suggests that greater equality leads to greater growth, partly because societies with a higher degree of income inequality have lower social cohesion. The Institut du Nouveau Monde argued that, when income inequality is too high, those who are rich lack the incentive to be more productive, to create jobs and to invest because the benefit of a marginal increase in income is not sufficient to encourage additional investment in the economy. Other witnesses had a different point of view, with the Conference Board of Canada, the TD Bank Financial Group and Canada 2020 observing that moderate income inequality can have a positive impact on economic growth, as it leads to economic efficiency, innovation and entrepreneurship. Mr. Veall mentioned research highlighting the low performance of Canada’s corporate sector in relation to other countries, which he argued is the result of a weak commitment to shareholder accountability and a high rate of insider trading. According to him, these factors might contribute to high executive compensation, and might make it hard for firms to raise capital or to replace ineffective corporate boards. The Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Nurses Association and United Way Toronto informed the Committee about research showing that countries that report the highest population health status are those with the greatest income equality, not the greatest wealth. Similarly, the Canadian Medical Association stated that income inequality can result in health inequality, and said that individuals with incomes below the “poverty threshold” experience relatively higher rates of suicide, mental illness, disability, cancer, heart disease and chronic illnesses, such as diabetes; as well, these individuals are 1.9 times more likely to be hospitalized, are 60% less likely to get tested for a health condition, and are 3 times less likely to fill prescriptions because of the associated costs. In terms of costs to the health care system, the Canadian Medical Association indicated that — according to one estimate — about 20% of total health care spending in Canada can be attributed to income disparities. It also referred to a 2011 study by the Saskatoon Poverty Reduction Partnership, which found that — over the course of a year — low-income residents had health care costs that were $179 million higher than those of middle-income earners. The Canadian Council on Social Development noted that if income inequality is not addressed, it will reduce social cohesion. According to Patricia Rogerson, who provided her views as an individual, equality in a country benefits the government and the citizens. United Way Toronto spoke about evidence from developed countries around the world, suggesting that higher rates of income inequality result in higher rates of social dysfunction at all income levels, not just in respect of those who are poor. According toRobin Boadway, a professor at Queen’s University who appeared as an individual, as Canada becomes more decentralized, groups of persons for whom the provinces are responsible have fallen behind and they obtain little support from the federal government. In his opinion, such imbalances threaten Canada’s social fabric. Mr. Walks said that Canadian cities are becoming more unequal and more polarized, with residents having either a high income or a low income. As well, he indicated that — over time — the incomes in each of the two groups will become more similar, while the differences between the groups will increase. A similar phenomenon was described by Mr. Hulchanski and Mr. Murdie, who argued that — in their opinion — the polarization of incomes in Canada’s large metropolitan areas over the 1970 to 2010 period was due to the decline of well-paid manufacturing jobs, the rising importance of highly paid managerial and professional employment, and the increased number of low-paid service jobs. According to them, as a result of these changes, recent immigrants — especially those in “precarious jobs” at the lower end of the job spectrum — have difficulty establishing themselves in Canada. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives mentioned research by the University of Toronto's Centre for Urban and Community Studies that showed that income inequality leads to people living in neighbourhoods that are either “rich” or “poor,” with fewer middle-class neighbourhoods. It also indicated that such neighbourhoods create problems for child development and the opportunities for children. According to United Way Toronto, when the incomes earned by those at the bottom and in the middle of the income distribution are low, spending by these individuals is constrained, which affects the economic growth of local communities. Regarding specific cities, the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction highlighted a report that found that the poorest 20% of Hamiltonians received 5% of the total income earned by Hamilton residents, while the richest 20% received 41% of that income. According to it, the report found that the richest 20% of Hamilton residents have approximately 8 times the amount of income of the poorest 20% of residents. According to a number of the Committee’s witnesses — such as Atira Women’s Resource Society, the Canadian Association for Community Living, the Face of Poverty Consultation and Canada Without Poverty — high degrees of income inequality can have negative social consequences affecting all of society, although specific groups — such as women, youth, seniors, Aboriginal peoples, immigrants and persons with disabilities — tend to be more affected by social exclusion. According to the C.D. Howe Institute, extreme inequality — including in terms of income, assets or wealth — leads to social unrest, as well as a lack of faith and trust in society. As noted by the Broadbent Institute, very unequal societies do much worse in terms of economic performance and social outcomes. Similarly, Mr. Wilkinson shared his view that, as income inequality in a society increases, social outcomes deteriorate rapidly when compared to those outcomes in societies with less income inequality. Poverty

and Employment Precarity in Southern Ontario told

the Committee that a large gap between those who earn a high income and those

who earn a low income can lead to an increased sense of social exclusion for

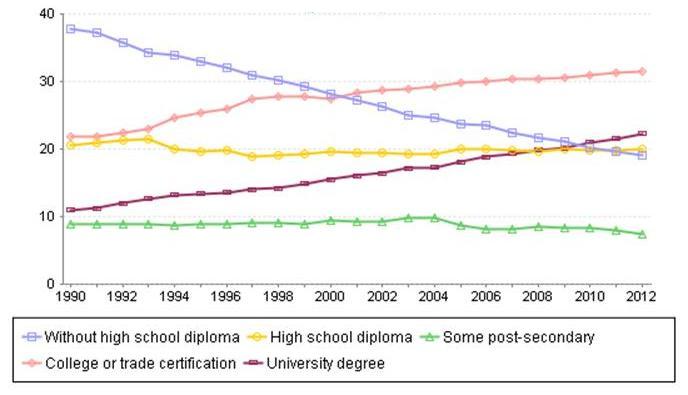

those in “precarious” employment. Ms. Rogerson noted that families with lower incomes are living in neighbourhoods that have schools with lower academic success, which results in limited access to post-secondary educational opportunities, restricted economic mobility and equality, and limited inclusion in community growth and development. CHAPTER FIVE: WITNESS VIEWS ON REDUCING INCOME INEQUALITY AND ITS IMPACTS IN CANADAThe Committee’s witnesses presented a range of proposals designed to reduce income inequality and its impacts in Canada. In that regard, suggestions were made with respect to the federal tax and transfer systems, a variety of employment-related considerations, education, health and specific groups, including Aboriginal peoples, women, persons with a disability, seniors and people with housing challenges. A. Federal Tax SystemIn commenting on Canada’s federal tax system and income inequality, witnesses made proposals about tax rates, brackets, credits and deductions, taxation of various types of income, taxation in relation to those with low income, families, children and persons with a disability, and tax avoidance. Regarding tax rates, brackets, credits and deductions, the Wellesley Institute, the Institut du Nouveau Monde, the Broadbent Institute, Campaign 2000, the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services, Canadians for Tax Fairness, Economicinequality.ca, the Face of Poverty Consultation and Mr. Corak advocated higher marginal tax rates for individuals with high incomes as a means by which to increase the redistributive effects of Canada’s tax system. Moreover, in order to increase federal tax revenue, Mr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick called for additional tax brackets for the top 1%, 0.1% and 0.01% of income earners. Canada Without Poverty and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives requested the creation of a new marginal tax rate of 35% for those earning $250,000 or more. Some witnesses were opposed to increases in marginal tax rates for individuals. The Frontier Centre for Public Policy speculated that an increase in personal income tax rates could have negative effects on economic growth, while the Canada West Foundation remarked that — as an alternative to higher taxes for the richest Canadians — measures to assist lower-income earners should be created. Mr. Veall argued for the elimination of tax expenditures that are mainly used by the affluent and that have not been successful in meeting their objectives, while the Institut du Nouveau Monde supported the elimination of tax credits that are used by high income earners. Similarly, the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services and Economicinequality.ca requested the elimination of — or limits on — tax expenditures that disproportionately benefit those who are wealthy, and Mr. Boadway advocated making all existing tax credits refundable for low-income individuals. Some witnesses spoke about specific credits and deductions. Mr. Veall urged the elimination of the Children’s Arts Tax Credit and the Children’s Fitness Tax Credit, which he believed would result in an additional $220 million in federal tax revenue. Canadians for Tax Fairness requested a reduction in tax deductions that it characterized as benefitting the rich, such as the limit on registered retirement savings plans (RRSP) contributions and the stock option deduction that is used by less than 1% of taxpayers. The Face of Poverty Consultation called for the transformation of certain tax deductions, such as those for contributions to pension plans and RRSPs, into tax credits. Witnesses supported a range of changes to the taxation of various types of income. Regarding investment income, Mr. Boadway characterized the dividend tax credit as a subsidy for shareholder income, and suggested the elimination of this credit and — instead — the taxation of dividends, capital gains and interest at similar rates. Mr. Corak supported an examination of the elimination of the favourable tax treatment of capital gains; as well, he argued that all sources of income should be taxed in the same manner. The Institut du Nouveau Monde requested the elimination of favourable treatment of capital gains, and the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services and Economicinequality.ca advocated the taxation of capital, including capital gains, at the same rate as employment income. In speaking about the taxation of corporate income, Mr. Boadway called for changes to the taxation of corporate income, and proposed a tax on “supernormal” profits. He also cited several international studies that advocate taxation of “above-normal” profits, and a deduction for equity and debt financing. Mr. Corak noted that corporate taxation of profits from the natural resources sector could be used to finance redistribution from higher income to lower income earners. Regarding the taxation of savings, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives requested that the Tax-Free Savings Account program not be expanded; the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services and Economicinequality.ca proposed elimination of — or limits on — the program. Ms. Robson suggested that savings programs should be made more progressive through refundable tax credits for savers, as well as through improved accessibility to the Canada Education Savings Grant and registered disability savings plans. Canadians for Tax Fairness requested the creation of an inheritance tax, to be applied on amounts exceeding $5 million. It argued that this measure, which should not be applied on family farms, could lead to an increase of $1.5 billion per year in federal tax revenue. Similarly, Mr. Corak suggested the creation of an inheritance tax to be applied on amounts above a certain threshold. However, he also said that — in the absence of an inheritance tax — a capital gains tax should be created in relation to the sale of a principal residence valued above a certain threshold. Other witnesses also advocated the creation of an inheritance or wealth tax, including Economicinequality.ca, the Face of Poverty Consultation, the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and Mr. Boadway. The Committee’s witnesses made a variety of comments about taxation in relation to specific groups, including those with low income, families and children. A number of witnesses felt that the WITB should be changed. For example, the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services called for an increase in the WITB, and Mr. Corak suggested that the level of benefits under the WITB should be increased to an amount that results in eligible Canadians having one half of the nation’s median income. He also suggested an increase in the income ceiling so that WITB eligibility would be extended to lower-middle income families, and an annual increase in the WITB based on growth in gross domestic product per capita or some other index. Similarly, the Frontier Centre for Public Policy requested an increase in WITB benefits, and argued that the increase could be funded through the elimination of tax deductions that benefit the affluent. Citizens for Public Justice advocated an increase in the WITB for unattached working-age individuals and an expansion in eligibility to include all households with earned income below the after-tax low income cut-off. The Broadbent Institute proposed a significant increase in the WITB to support the working poor and individuals with “precarious” work, while Canadians for Tax Fairness suggested an increase in WITB benefits to assist working poor families who have never received social assistance. Ms. Rogerson supported an exemption from income taxation for individuals with income below the “poverty line.” Kathleen A. Lahey requested a gender impact analysis of the Income Tax Act provisions that treat spouses and common-law couples as interdependent and integrated tax units, and that affect eligibility for federal and provincial/territorial support programs. Regarding income splitting for tax purposes, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives argued that income splitting for families with young children should not be permitted, as it could increase income disparities between families. The Broadbent Institute proposed an increase in the maximum level of support provided through the CCTB and the NCBS so that the combined amount would equal the full cost of raising a child; according to it, the benefit increases could be funded through elimination of the Universal Child Care Benefit (UCCB). Campaign 2000 and Citizens for Public Justice suggested an increase in the combined maximum annual level of the CCTB and the NCBS to $5,400 per child, with revenue obtained through elimination of the UCCB and the Children’s Fitness Tax Credit used to fund the increased benefits. The Women's Action Alliance for Change Nova Scotia and Canadians for Tax Fairness advocated an increase in the maximum annual CCTB benefit to $5,400 per child; in the view of Canadians for Tax Fairness, the increase could be funded through the elimination of the UCCB. The Frontier Centre for Public Policy proposed that eligibility for the UCCB be limited through a means test, with resulting savings allocated to low-income parents. B. Federal Transfers to the Provinces/TerritoriesIn speaking about transfers to the provinces/territories, witnesses focused on such issues as enforcement, accountability and standards for the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and the Canada Social Transfer (CST). The Broadbent Institute proposed that conditions in relation to the use of funds be imposed on additional federal funding, while the Canadian Association of Social Workers commented on the lack of provincial accountability for the delivery of services, and made a variety of requests: the creation of an accountability framework that includes a process for reporting and enforcing conditions; specific objectives and standards for the flexible delivery of services; and an overall vision or national strategies to ensure that social programs meet the needs of Canadians. The Canadian Federation of University Women and YWCA Canada advocated the reinstatement of legally enforceable standards for social assistance, such as those that existed under the Canada Assistance Plan. Regarding the calculation of federal transfer payments, Mr. Boadway proposed that the Equalization system return to a formula-based approach, that the CST grow at the average rate of growth of provincial program spending, and that the CHT and CST cash contributions be adjusted based on provincial revenue capacities. The Atira Women’s Resource Society, the Women's Action Alliance for Change Nova Scotia, andMr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick advocated an increase in the CST to address economic inequality through social assistance. According to Mr. Veall, equal access to high-quality schooling and prenatal health has resulted in high intergenerational mobility in Canada. He noted that provincial budget reductions may hamper such mobility, and urged the federal government to work with the provinces, perhaps through the new Equalization formula, to ensure that the provinces continue to deliver high-quality education to individuals, regardless of socioeconomic status. Regarding a new transfer specifically for education, Mr. Boadway suggested the creation of a post-secondary transfer that would be similar to the CHT and the CST. Campaign 2000 requested $1.3 billion for a new transfer to assist the provinces in providing publicly managed, owned and funded early childhood education and child care. The Broadbent Institute called for the replacement of provincial/territorial social assistance programs with a federal income support program for working-age adults, delivered as a negative income tax. C. Employment FactorsIn speaking about employment-related proposals that they believe would reduce income inequality and its impacts in Canada, witnesses focused on early learning and child care, EI benefits, active labour market measures, labour mobility and labour standards. A number of witnesses supported the development of a national, publicly funded child care program, which is thought to facilitate labour market participation. In particular, the Women's Action Alliance for Change Nova Scotia, Generation Squeeze, the Social Planning Council of Winnipeg, the Canadian Federation of University Women and YWCA Canada, the Child Care Advocacy Association of Canada, and Mr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick supported the creation of such a program. In commenting on improvements to the EI system, Mr. Boadway highlighted the need to coordinate the functioning of the EI program with provincial social assistance programs to eliminate gaps in coverage and facilitate a smoother transition between the two programs. In particular, he advocated the establishment of a two-tiered system to eliminate the tendency to move from EI to social assistance, as EI eligibility can change based on such factors as thresholds for hours worked, payment of EI premiums, disability status and transition to retirement. According to him, one tier would be available based on the current system for those who are unemployed on a short-term basis, while benefits would be provided on the basis of need for those unemployed over a longer period. To fund this initiative in an “effective” and “fair” manner, he argued that the EI program should be financed from general federal revenue rather than through a payroll tax, which he characterized as more regressive. Regarding the effects of globalization, automation and the transition from low- to high-skill jobs, Mr. Corak proposed that part of the EI program be modified to become a form of wage insurance to meet the needs of longer-tenured workers affected by permanent layoffs in their sector or industry. As well, he argued for tax reforms that would permit individuals to average their earnings over a period of several years so that earnings and the accompanying taxes owing would fluctuate less over time. Moreover, he suggested that the EI system should be modified to include a lifetime “bank” of leave credits that parents could access for family reasons. In relation to active labour market measures, Ms. Rogerson, the Institut du Nouveau Monde, and Mr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick called for better coordination between worker training and the EI program through increased federal support allocated to EI Labour Market Development Agreements with the provinces, and to non-EI-related programs that support training and skills development. The Canada West Foundation commented on labour mobility, indicating that federal efforts to address income inequality should not interfere with interprovincial labour mobility. It argued that, in addition to removing barriers to labour mobility, the government should focus on meeting the needs of employers where the excess demand for skilled workers is greatest, most notably in resource extraction industries in Canada’s western provinces. According to it, the federal tax credit for moving expenses for workers making a significant work-related move to other parts of the country should be maintained. Some witnesses — including Ms. Fortin, the Broadbent Institute, the Canadian Union of Public Employees, Generation Squeeze and Mr. Hulchanski and Mr. Murdie — highlighted the issue of labour standards, and suggested that — as a means of reducing the gap between the wages of the highest and the lowest income earners — the government should adopt policies that improve these standards and that are more supportive of the collective bargaining and union certification processes. A number of the Committee’s witnesses — including Ms. Fortin, the Women's Action Alliance for Change Nova Scotia, the Canadian Association of Neighbourhood Services, the Broadbent Institute, Canada Without Poverty, and Mr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick — commented on the need for adequate wages for low-income earners, arguing that the federal government should work with provincial/territorial governments in re-establishing an adequate federal minimum wage that reflects the cost of living by region and that increases over time to compensate for inflation. In terms of improving non-wage labour standards, Generation Squeeze supported extending EI parental leave from 12 months to 18 months, and reducing the work hours of dual-earner families from 80 hours to 70 hours per week through adaptations to both overtime and employer-paid EI and Canada Pension Plan (CPP) premiums to make it less costly for businesses to employ workers up to 35 hours per week and more costly for them to do so for hours in excess of this amount. Ms. Robson requested that the federal government, in cooperation with provincial governments, explore avenues for ensuring the portability of non-wage benefits — such as pensions, disability insurance, and health and dental benefits — for Canadians who transition from secure jobs that provide such benefits to less secure jobs that do not. As well, Mr. Labonté, Mr. Ruckert and Mr. Caldbick proposed that the federal government review its current austerity measures, arguing that expanding public-sector employment during an economic recession would have a much greater effect on growth than does attempting to increase economic growth through the tax system. D. EducationWitnesses proposed a variety of measures related to education that, in their view, would reduce income inequality and its impacts in this country. In particular, they commented on post-secondary education, financial literacy and early childhood education. According to Ian Lee, a professor at Carleton University who appeared as an individual, the government should focus its efforts on encouraging the 45% of Canadians without a post-secondary education to return to school. He provided the Committee with a figure showing, for the 1990–2012 period, the highest level of educational attainment for individuals 15 years of age and older; an updated version of this figure appears as Figure 13. The Women's Action Alliance for Change Nova Scotia called for the creation of a new federal transfer that would enable reduced tuition fees, while the Frontier Centre for Public Policy supported an increase in funding for student loan and grants programs, but with a focus on low-income individuals. Similarly, Mr. Boadway advocated an increase in the amount of the Canada Learning Bond, and argued that education-related tax credits should be conditional on low parental income. The Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction also spoke about the Canada Learning Bond, proposing that it be provided automatically to eligible families when tax returns are filed. Figure 13 — Highest Level of Educational Attainment of Individuals, 15 Years of Age and Older, Canada, 1990—2012 (%)

Source: Updated version of a figure provided to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance by Ian Lee, Carleton University, 25 April 2013.