RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES IN NORTHERN CANADAINTRODUCTIONThe development of natural resources in Canada’s remote northern regions faces a number of social, economic, infrastructural, environmental and regulatory challenges. The growing world demand for energy, metals and minerals, petrochemicals, and diamonds offers promising opportunities for Canada’s northern natural resources sector. In order to gain a better understanding of the various opportunities and challenges in the development of mineral and energy resources in Canada’s North, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources undertook a study on resource development in northern Canada.[1] The study includes five main components:

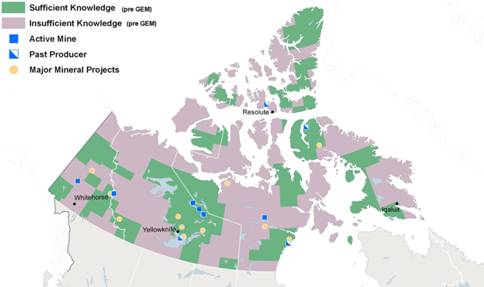

This report focuses on the geoscience, socio-economic issues, the regulatory challenges of mineral and energy resource development in northern Canada, as well as the case study on the Ring of Fire. Information on these topics is based on testimony from a wide range of witnesses from government, industry, Aboriginal groups, academia, and environmental organizations. GEOSCIENCEA. OverviewGeoscience, particularly geo-mapping, can be used to guide investment decisions and help governments and the private sector assess resource potential in northern Canada. As mentioned by James Ferguson, Chair and Acting President of the Geomatics Industry Association of Canada (GIAC), “Geomatics (also known as geospatial technology or geomatics engineering) is the discipline of gathering, storing, processing, and delivering geographic information, or spatially referenced information”.[2] According to Keith Morrison, Chief Executive Officer at Gedex Inc., low-cost, high-resolution, and high-quality geological information in northern Canada’s vast territory and remote environment is fundamental to reducing the investment risks and uncertainties associated with resource exploration and development in the north.[3] Approximately 60% of the Canadian territories’ lands lack sufficient geo-science knowledge, as Figure 1 demonstrates.[4] Figure 1: Geoscience Knowledge in the Canadian Territories

Source: Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) document presented to the Committee. According to Steve MacLean, President of the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the increasing global demand for gold, precious rare earth minerals, petrochemicals, diamonds and water has led northern Canada to an “unprecedented boom in demand for prospecting, exploration, and exploitation.” Geoscience initiatives have helped produce accurate maps of resource activity in the north.[5] Moreover, he stated that globally “[...] the programs and activities of the Canadian space program support the Arctic and northern strategy; sovereignty and security and the safe navigation of ships in our icy waters; Canadian Forces deployments at home and abroad; fishing patrols and offshore pollution detection and interdiction activities; atmospheric and environmental monitoring related to precision weather forecasting and climate change; and the exploitation, development, and sustainable management of Canada’s natural resources, especially in the north.” He added that “robust, and redundant space-driven communications, weather, and navigation services [are needed] to fully realize and capitalize [the North’s] potential for sustainable development, now and in the future.”[6] James Ferguson (GIAC) pointed out that “users of geomatics are truly cross-sectoral. [They] come from sectors that include infrastructure and critical infrastructure; transportation — land, air, and sea; emergency management; public health and biosecurity; resource management; mining; petroleum resources; the environment; national defence and border security; utilities and telecommunications; forestry; fisheries; manufacturing; and trade and retail services.”[7] According to him, even though Canada was “an international leader in geomatics post-World War II and into the 1980s, its status and ability at the federal level has fallen behind much of the developed world.” The GIAC is of the view that “the lack of a coherent, practical, and actionable national strategy and plan is at the core of this decline.”[8] Although Canada is ahead of many countries, the state of “adequate geoscience knowledge” (mapping) remains more advanced in countries like Australia and Mexico.[9] David Scott, from the Geological Survey of Canada, Northern Canada Division at Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), stated that Canada is “somewhere in the middle” in terms of geo-science competitiveness among countries, pointing out that, “owing to the sheer size of Canada and the logistical difficulties of working in remote areas of the country, particularly in the north, [geomatics in Canada are] not quite where [they] need to be from a private sector investment perspective.”[10] The work of NRCan south of 60 degrees has been largely completed, according to him. “The provinces work on the next generation of detail.”[11] The federal government is focusing its geoscience efforts north of 60 degrees, through programs such as NRCan’s Geo-mapping for Energy and Minerals (GEM).[12] James Ferguson also indicated that, at the provincial level: there are a number of examples of how government can partner with industry to ensure accessible data is available and to work together to prioritize the gaps in existing locations. In the field of geomatics, the following program is an example that is in place in Alberta: Spatial Data Warehouse Ltd. is an Alberta-registered, not-for-profit company created in 1996 to take over and fund digital mapping activities that were previously undertaken and funded by the Government of Alberta. It has proven to be one of the most successful P3 [public-private partnership] initiatives within the province of Alberta. Spatial Data Warehouse's objective is to provide for the long-term management, updating, storage and distribution, and associated funding of digital mapping data sets that collectively make up Alberta's digital mapping infrastructure.[13] Since the late 1950s, Canadian geoscience has gone through major technological advances. As illustrated by Brian Gray of the Earth Sciences Sector, NRCan, “today we use modern tools to collect and distribute information beyond the typical bedrock geology mapping [and] [t]he modern mapping methods provide digital information distributed freely via the Internet. [...] The technology we're using: airborne geophysical surveys measure physical properties of the bedrock from the aircraft, such as a helicopter or a light fixed-wing aircraft; the aircraft flies back and forth over the land along parallel lines spaced about 400 metres apart, and the aircraft is about 150 metres off the ground. Down on the field level, we have field data collected by geologists using hand-held devices with pinpoint GPS accuracy.”[14] With measurements of the magnetic properties of rocks below the soil, it is now possible to get a more complete picture of the bedrock,[15] even when it is deeply buried. Gedex’s imaging technologies “are applied specifically to subsurface imaging, providing new data that can be used to interpret geology in terms of supporting petroleum, mining, and water exploration and development”.[16] The technology can provide data from the surface down to depths of about 10 kilometres, including sub-ice measurements, to interpret subsurface geology.[17] B. Government InitiativesThe Government of Canada has launched two programs in order to advance geo-science knowledge — particularly geo-mapping — across Canada:

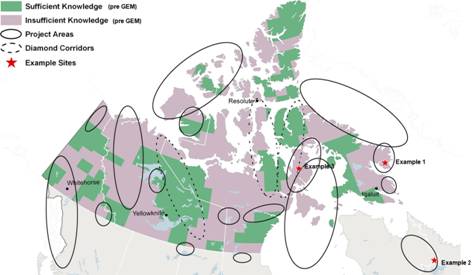

The GEM program is the federal government’s “flagship program under the northern strategy to address those areas of Canada where the basic framework mapping is not adequate to support private sector investment.”[19] According to Brian Gray, approximately 75% of the GEM program targets areas north of 60 degrees, while 25% is devoted to the northern parts of British Columbia, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba.[20] Moreover, NRCan administers other geoscience programs, including a climate change geoscience program focusing largely on the north, a groundwater geoscience program mapping groundwater aquifers across Canada (exclusively south of 60 degrees), and the “targeted geoscience initiative”, which targets areas mostly south of 60 degrees. Under the intergovernmental Geoscience Accord, initiated in 1996 and renewed every five years, NRCan works with the provinces and the private sector to develop new models and exploration techniques targeting deeply buried ore deposits.[21] Figure 2: GEM Project Areas

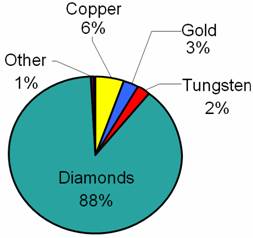

Source: Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) document presented to the Committee. The Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor) has also invested $10.7 million towards geo-science research, through the Strategic Investments in Northern Economic Development (SINED) program. A database of geo-science was developed through the program, and is currently used to assess resource potential in the north.[22] C. Challenges and OpportunitiesConsidering the geological diversity of northern Canada, current GEM projects could help identify a wide range of mineral and energy resources (Figure 2), including new gold and precious metals, diamond-bearing kimberlites, oil and natural gas reserves, uranium reserves, and various base metals (e.g. copper, zinc, nickel, iron, and lead).[23] Furthermore, according to Richard Moore, Chair of the Geosciences Committee in the Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC), the information gathered from the GEM and TGI programs “increases the knowledge of Canada's natural resources; encourages mineral exploration and mine development; contributes to economic development, particularly in the north; attracts investment; and contributes to the professional development of geology students.”[24] Pamela Schwann, Executive Director of the Saskatchewan Mining Association, told the Committee that geosciences programs, particularly mapping skill programs and large-scale airborne geophysical programs, are especially helpful to the junior companies that may not have the resources to carry out their own geosciences research.[25] John Gingerich, President and Chief Executive Officer of Advanced Explorations Inc., stated that mapping programs are “the lifeblood of the exploration industry”.[26] According to James Ferguson, “a national geomatics strategy [beyond mapping] would also address the strategic importance of geomatics technology to a modern economy and society by helping facilitate the effective application of geomatics in [...] our key national policy issues, such as energy, sovereignty, environment, public safety, natural resources, health, and others.”[27] According to Richard Moore, “the geoscience knowledge provided by federal, provincial, and territorial governments as a public good is widely acknowledged to be one of Canada's competitive advantages in attracting mineral exploration, [... and is] essential for maintaining Canada's role as the leading destination for exploration investment.”[28] An analysis by the PDAC estimates that every dollar spent on geo-mapping by the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC) may generate roughly five dollars in exploration, and possibly $125 in mining development (including downstream impacts, such as job creation), within a few years.[29] On the other hand, Brian Gray, from the Earth Sciences Sector of NRCan, told the Committee that northern Canada’s remoteness and shortage in basic infrastructure (e.g., roads, boats, planes, hotels, etc.) would likely delay the return on investment of the GSC’s geo-mapping initiatives.[30] According to James Ferguson, Canada’s geomatics business includes over 2,000 small, medium and large firms, providing close to 25,000 jobs across the country. The estimated annual gross revenue generated by geomatics firms exceeds $2 billion, including approximately $0.5 billion earned as export revenue. Furthermore, he stated that, according to a report prepared for the Canadian Council on Geomatics, employing geomatics more effectively could generate GDP gains of 0.6% to 1.2% (or approximately $9.5 billion to $18.9 billion annually). He added that, in another analysis funded by two private Canadian geomatics firms in 2010, Dr. Ian Lee, MBA director of the Carleton University Sprott School of Business, predicted GDP gains in the range of $7.3 billion to $14.4 billion.[31] Steve MacLean of the CSA stated that, in the next decade, over 250 satellites will be launched by a number of countries, many capturing images of Canada. To maximize the benefits of these satellites, Canada’s integrated space-ground infrastructure needs to be expanded in order to “ensure the development of [Canadian] space infrastructure and take advantage of the capture, archiving, processing, and dissemination of this complementary data [...].” He added that establishing common standards, particularly a common geo-reference for data storage, is necessary to allow for data usage by multiple entities.[32] According to John Gingerich, “the purpose of mapping has land use planning considerations [and that] [t]he problem is that people are making decisions on what land will be good for exploration or good for biodiversity without having the database.”[33] MINERAL RESOURCE DEVELOPMENTA. OverviewThe growth of Canada’s mining industry has been evident in recent years. Since 2004, Canada has attracted between 16% and 19% of the world’s share of mineral exploration.[34] Between 2006 and 2010, northern mineral production increased by about 53%. Nunavut, Yukon and the Northwest Territories accounted for about 6.3% of the value of Canada’s total mineral production in 2010, with diamond mining representing about 88% of all northern mineral production in terms of value.[35] Mineral exploration and deposit spending amounted to about $498.1 million for the three Canadian territories the same year.[36] Figure 3 presents an overview of mineral production in northern Canada. Figure 3: Mineral Production in Northern Canada

Source: Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) document presented to the Committee. The mining sector is the main driver of economic activity in northern Canada, both north of 60 degrees and in the northern regions of many provinces. In 2010, Canada’s mining industry provided approximately 308,000 direct jobs across Canada. Furthermore, according to some estimates, for every direct mining job, at least two indirect jobs are created in a wide range of sectors (e.g., financial, legal, construction, catering, etc.).[37] The following are examples of some of the impacts of mining in specific jurisdictions:

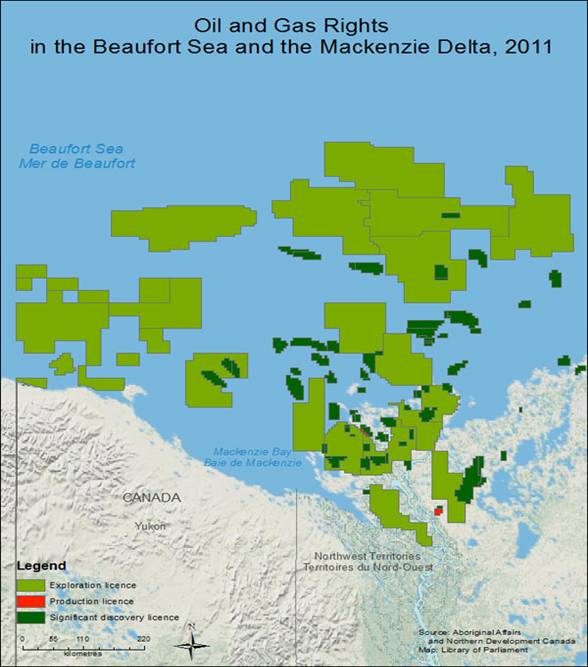

Exploration spending in the north, which has typically fluctuated over the years, is expected to increase due to the growing interest in northern resource development. According to Pierre Gratton, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Mining Association of Canada, “there is a race around the world for developing and finding new [mining] projects, and Canada is well positioned to benefit from that.”[43] David Kilgour, councillor for the City of Greater Sudbury, also suggested that Canada needs a policy framework that would help the resource-rich areas of the country realize their full potential in terms of mineral resource development.[44] The Mining Association of Canada has estimated “some $137 billion in potential new investment in Canada over the next five to ten years in different projects or in project expansions across the country.” [45] The new mining developments are expected to diversify Canada’s mining commodity base beyond diamonds to include minerals such as gold, iron ore, zinc, lead and rare earth elements.[46] As of October 3, 2011, there were 48 mining projects undergoing environmental assessment in Canada, including 14 projects in the Canadian territories, representing “somewhere between $7.5 billion to $8.5 billion in investment.” [47] The approval of these projects could double the number of full-time jobs in the territories, according to NRCan. ENERGY RESOURCE DEVELOPMENTA. OverviewPetroleum resources on federal lands north of 60 degrees are regulated by the National Energy Board (NEB) in accordance with the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act (COGOA) and the Canada Petroleum Resources Act (CPRA). The two statutes also give the Oil and Gas Branch of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) the statutory authority to issue exploration, discovery and production rights in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and in offshore areas north of 60 degrees.[48] According to Mimi Fortier, Director General at the Northern Oil and Gas Branch of AANDC, “only about one fifth of the Arctic Ocean margin has been explored. Conventional oil and gas resources from the north account for approximately 33% of Canada's remaining conventionally recoverable resources of natural gas and 35% of the remaining recoverable light crude oil. Every year, the Northern Oil and Gas Branch submits an annual report on the administration of lands to Parliament...and is available on the department website.”[49] While there is significant potential for conventional oil and gas resource development in the region, there is also evidence of “industry’s rapidly growing interest in Canada’s shale resources [from] 500 kilometres north of 60 to the central Mackenzie Valley.”[50] In 2011, the Oil and Gas Branch issued 11 new exploration licenses to petroleum companies for exploring shale formations; a work expenditure commitment totalling $534 million. “New hydraulic fracturing technologies have the potential to make this vast reserve accessible, but this potential has to be proven by exploration before economics of shale development in this region can be evaluated.”[51] Further north, the Beaufort Sea and Mackenzie Delta region has significant potential for petroleum resource development, with more than 60 discoveries to date. Several companies have been granted deep-water exploration licences in the Beaufort Sea since 2007 (Figure 4). Their cumulative work commitments account for almost $2 billion.[52] Figure 4: Oil and Gas Rights in the Beaufort Sea and the Mackenzie Delta, 2011

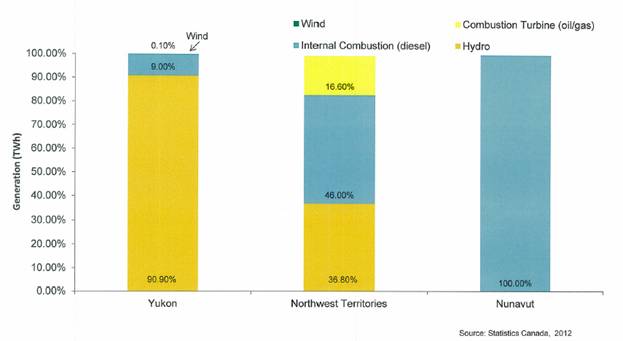

Source: Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Northern Oil and Gas Branch, Oil & Gas Dispositions, June 2012; adapted by the Library of Parliament. SOCIO-ECONOMIC ISSUESA. Aboriginal Consultation and Land SettlementIn a series of landmark decisions, the Supreme Court of Canada has articulated the Crown’s duty to consult with Aboriginal groups regarding decisions that could have adverse effects on Aboriginal interests. Crown decision makers have an obligation to be informed of the implications of their actions on Aboriginal peoples, including three main considerations: Crown conduct, potential or established Aboriginal treaty rights, and potential for adverse impacts.[53] According to Michael Hudson, from the Department of Justice, there is a spectrum of possible Aboriginal claims, ranging from “relatively weak” (e.g., concerns regarding a specific species for hunting, which may require information sharing or general public outreach to Aboriginal communities) to “very strong” (e.g., a permit that could lead to destructive activity to Aboriginal lands, which may call for a more involved consultation process). Aboriginal groups do not have a veto on development decisions; however, there is “an expectation of accommodation measures that would be commensurate with the negative impact on the [Aboriginal] interest.”[54] Many resource companies have incorporated Aboriginal consultation provisions in their business model since the Supreme Court issued its “Duty to Consult” decisions six years ago.[55] However, according to him, the lack of specific rules (or a code) to regulate Aboriginal consultations often presents challenges to the consultation process. On the other hand, “the nature of the consultation duty and the fact that it is often very case specific doesn’t lend itself well to a code.” He added that the government has been “very successful in recent years in using the interim guidelines to lay out in a great deal of detail for both project proponents and Aboriginal peoples how information that each of them provide will be integrated into the decision-making within the government.”[56] Some mining companies expressed the need for more clarity regarding duty to consult provisions. According to Hughie Graham, President of the Northwest Territories Chamber of Commerce, “from industry’s perspective, there is a critical need to resolve what the crown’s duty is, and what industry’s role is, especially given that the duty to consult and to accommodate are fundamentally obligations of the crown.”[57] There have been references from several witnesses that some provinces, such as Quebec, because of its experience with Hydro Quebec on the James Bay project, and Saskatchewan, had better practices in place related to the duty to consult with Aboriginal communities. More clarity is also needed about what is considered to be meaningful engagement with Aboriginal communities. As stated by Karina Briño, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Mining Association of British Columbia, “what is the role of industry in terms of benefits going towards aboriginal communities...There needs to be clarity around that, in terms of when my responsibility stops versus the government’s.”[58] Speaking of offshore oil and gas development in the Arctic, Martin Von Mirbach referred to the Beaufort Sea partnership as a good example of multi-stakeholder consultation and planning process. The Beaufort Sea partnership brought together Inuvialuit communities, industry, governments, academia, and regulators to develop an integrated ocean management plan for the Beaufort Sea.[59] He stated that “once it’s done, it’s more politically robust” because all of the stakeholders interests have been considered, and are included in the plan.[60] In reference to energy resource development in northern Canada, Mimi Fortier told the Committee that “the Aboriginal groups are engaged from a very early point. For instance, there’s a great deal of leadership among the Inuvialuit to make sure that the Aboriginal Inuvialuit are very informed. The industry often converses with the Inuvialuit far more than they do with governments. There is definitely Aboriginal planning that goes into reaching agreements with the companies in terms of training, opportunities for employment and business opportunities.”[61] Most of northern Canada includes modern land claim settlements with Aboriginal consultation provisions, particularly regarding environmental assessments.[62] However, unsettled land claims continue to present considerable challenges to both Aboriginal communities and investors, according to a number of witnesses.[63] Anil Arora, from the Minerals and Metals Sector of the NRCan, pointed out that “…outstanding land claims...contribute to uncertainty and investment risks. These risks, along with withdrawals of lands for conservation, have created some concerns by industry.”[64] Mark Kolebaba, President and Chief Executive Officer of Diamonds North Resources Ltd., told the Committee, that “from our point of view as a company, we spend 95% of our budget in Nunavut and about 5% in the NWT, which is based solely on the fact that the land is not settled. A huge amount of money is not put into the NWT for that reason.”[65] Ugo Lapointe, from the Coalition pour que le Québec ait meilleure mine, indicated that some First Nations in Quebec, such as the Innu First Nation, are “still struggling with their traditional entitled rights, [which] should be settled [to create] a more stable climate both for communities and investors.”[66] Similarly, Glen Sibbeston, Chief Pilot at Trinity Helicopters, stated that if Canada is to take the best advantage of its resources, development interests need to be aligned with the interests of First Nations, by “completing the land claims in such a way that Aboriginal people prosper as their lands produce.”[67] Anil Arora noted that “there is work under way by the federal government related to land claims and land use planning that should improve the current situation.”[68] Ginger Gibson MacDonald, an Adjunct Professor from Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering at the University of British Columbia, told the Committee that resource development has to be in line with treaty obligations pertaining to the Aboriginal people and their right to pursue their way of life. She spoke about the need to protect water and animal habitats so that Aboriginal families can maintain their traditional livelihoods through hunting and fishing.[69] B. Benefits to Northern CommunitiesThe mining industry offers a number of socio-economic benefits to northern communities. As noted by David Kilgour, from the City of Greater Sudbury, “it offers excellent employment opportunities for educated and skilled workers alike, and will provide important economic development opportunities for all of northern Canada.”[70] According to testimony from a number of witnesses, there has been progress with regard to Aboriginal employment in the northern mining industry.[71] Tom Hoefer, Executive Director of the NWT and Nunavut Chamber of Mines, told the Committee that “[m]ining is the largest employer of Aboriginal people in Canada [and that] [i]t's also now the largest private sector employer of Aboriginal people in the north”.[72] According to Ronald Coombes, President of White Tiger Mining Corp, “exploration for minerals creates opportunities for high-paying jobs and other forms of indirect opportunity, such as environmental, food, fuel and supply contracts. These are just a few of the associated benefits available for all local community people. The policy throughout the mining industry is to retain qualified persons within the communities nearest to exploration projects. This, in most cases, means direct opportunities for First Nations communities.”[73] Hilary Jones, General Manager of the Mine Training Society, told the Committee that by 2019, Nunavut, Yukon and the NWT may have as many as 5,000, 2,500 and 2,000 mining jobs respectively. To put things in perspective, she also pointed out that “for every one job created in mining, three other jobs are created in mine services and services in general to support the miners’ families.”[74] To illustrate the importance of mining activities in small northern communities, Peter Tapatai, a representative from Hamlet of Baker Lake, stated that the Nunavut Meadowbank gold mine will account for a significant portion of the territory’s GDP, and is already providing over 100 jobs as well as training and business opportunities.[75] The Honourable Peter Taptuna, Minister of Economic Development and Transportation at the Government of Nunavut, also indicated that “over the next decade, several thousand Nunavut residents will have the opportunity to gain employment in the mining industry, if they are prepared to take advantage of the opportunities.”[76] He added that “some of these developments [are] encouraging younger people in the smaller communities to stay in school. In the past, there was very little encouragement for some of these young folks to stay in school because nothing was happening at the end of the line.”[77] Some witnesses pointed out that increases in exploration and development do not necessarily translate to local job impacts. According to Brennain Lloyd of Northwatch, “we saw a 22% increase in the value of mined commodities from 2005 to 2006, just a two-year span, a 45% increase in value of mineral potential, but only a 7% increase in the number of jobs. So for a community looking at employment benefits, we have to look very carefully at this trend of modernizing mining and that volume ratio of mine to jobs is shrinking.”[78] He added that the lack of local ownership and local decision-making can also be a problem for mining communities. “There is a sense in the community that when you have decisions being made on an economic basis by people who are further away, the decisions are less beneficial to the community”.[79] Additionally, Ramsey Hart, Co-manager of Canada Program with MiningWatch Canada, pointed out that northern mines are increasingly based on fly-in camps rather than the development of new mining towns. He also stated that employment at the Meadowbank Mine in Nunavut has had a high turnover rate and that local hires often face a ceiling due to a lack of training.[80] By contrast, some witnesses mentioned that in the Yukon and the NWT, economic impact and benefit agreements between industry and Aboriginal groups have been effective in ensuring that local communities benefit from development.[81] According to Hughie Graham, these agreements, which require that a certain percentage of employees be northern-Aboriginal, have been beneficial for Aboriginal business development. He stated that, “[...] 75 to 100 Aboriginal-owned businesses have been created through impact and benefit agreements in the last 16 years in Northwest Territories.”[82] Also commenting on those agreements, Ginger Gibson MacDonald said that: One of the wonderful things about the mines having impact and benefit agreements is that there are dollars that are free to apply to things like education. For example, the Tlicho Nation has $800,000 yearly that they allocate to scholarships for people who are pursuing their education in the south. Those people are then becoming lawyers, or all sorts of different careers are opening up to them. The possibility for them to start to be promoted if they choose to be in mining is certainly there. The impact and benefit agreements have been absolutely fundamental to aboriginal business in the north. Those agreements in themselves require the secure unbundling of contracts so that things aren't so big that you can't possibly bid on them. There's access to capital through government programs. The guarantee, through the agreements, of contracts such as site services have been fundamental to businesses of the north, and have grown them.[83] On the subject of Aboriginal business development, Gordon Macdonald, Principal Advisor on Sustainable Development in Diavik Diamond Mines Inc., told the Committee that “we spend a lot of time trying to break up our procurement and our contracting to enable smaller contracts, to help develop Aboriginal businesses. They have been very successful. They’re starting to work outside of our employment and in other mines and have even started to look internationally. I think that kind of business development with Aboriginal communities is probably the most long-lasting opportunity for them.”[84] Pierre Gratton noted that industry had “a significant and potentially transformative impact” in the north. For example, “there has been some $4 billion in business procurement with Aboriginal businesses in the Northwest Territories.”[85] Moreover, some witnesses mentioned the potential involvement of northern Aboriginal communities in mining projects through equity participation. Donald Bubar, President and Chief Executive Officer of Avalon Rare Metals, told the Committee that his company was “in the process of negotiating an equity participation arrangement with [their] aboriginal partners. Right now that is our objective, and that's what we think the future is for First Nations participation in the mineral economy in the north.”[86] Robin Goad, President of Fortune Minerals, added that “equity participation would certainly be one of the issues that would be under negotiation as part of an IBA.”[87] Wes Hanson, President and Chief Executive Officer of Noront Resources, pointed out that “[...] in order for the communities to earn an equity ownership position in these mineral companies, they have to start establishing businesses, whether those are hotels, power generation, or running a filtering and drying plant. They have to take advantage of the opportunities that are there for them now, generate cash flow, and invest it in the mining companies.”[88] C. Labour Force Capacity1. Skilled Labour ShortageSeveral witnesses have identified skilled labour shortages as a significant challenge in mineral and energy resource development. Karina Briño stated that the “the latest statistics, at a national level, indicate that Canada will need about 112, 000 skilled workers for the mining sector alone.”[89] However, as pointed out by Francis Bradley, Vice-President of Policy Development at Canadian Electricity Association, this challenge is not unique to the resource development industry or the North. Many different industry sectors across North America (e.g. electricity and information technology sectors) are competing for the same skilled workers and equipment.[90] According to Anil Arora, the problem is more pronounced in the north due to the region’s relatively low population and education levels.[91] Hilary Jones told the Committee that a lack of training is a key factor contributing to unemployment rates and labour shortages in northern communities. “The problem or challenge is that the people who are available for jobs do not have the skill sets to meet the requirements for employment in the mining industry. Let’s keep in mind that 78% of those jobs in the mine site are for skilled and semi-skilled workers. Fewer than 5% are for those individuals who would qualify as labourers.”[92] Speaking of the labour shortages in Yukon communities, Sandy Babcock, President of the Yukon Chamber of Commerce, noted that “the temporary foreign workers program has been extremely successful and beneficial to our business community, particularly in the capital city of Whitehorse.” [93] Karina Briño agreed that the foreign workers program is helping industry in meeting the immediate demand for labour; however, more support from the federal and provincial governments is needed for Aboriginal training and capacity building.[94] Gil McGowan, President of the Alberta Federation of Labour, cautioned that the temporary foreign workers program perpetuates the labour shortage problem into the future. Currently, there are about 65,000 temporary foreign workers in the province of Alberta, and there are about 20,000 working in the oil sands and in construction. According to him, “employers are choosing temporary foreign workers over apprentice training, and in the process” they are not training the next generation of Canadian tradespeople. In other words, by not training “the next generation of tradespeople, we are locking ourselves into a future of skilled labour shortages.”[95] Ugo Lapointe of the Quebec Mining Association also commented on an increasing reliance on international workers. He suggested that “maybe we need to consider waiting to extract some of the deposits and bring in the benefits in the longer term for the regions and the province.”[96] 2. Training and Capacity BuildingA number of witnesses underlined the importance of developing human resources in Canada’s North. Considering the relatively high costs associated with attracting labour from the southern parts of Canada, Mitch Bloom, from the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency, highlighted the economic advantages of maximizing local expertise through training.[97] According to Hilary Jones, “there is a compelling business case for continued human resource investment by the federal government in northern people, not the least of which is the healthy and growing return on investments for resource royalties.”[98] There are three mine training organizations (MTOs) in the north: the NWT’s Mine Training Society, the Yukon Miner Training Association and the Kivalliq Mine Training Society, which she hopes will soon become the Nunavut Mine Training Society. She noted that the mine training societies have been working to ensure that local Aboriginal populations are able to take advantage of the economic and employment opportunities within the mining sector. Furthermore, she pointed out that about 25% of the Mine Training Society’s trainees are Aboriginal women, which is higher than the 5% national average of women in the mining sector.[99] According to Karina Briño, the mining sector in British Columbia has undertaken a number of initiatives to address the workforce shortages, and to increase Aboriginal training in mining. The British Columbia’s School of Exploration and Mining offers environmental monitoring training to Aboriginal youth, allowing them to develop transferable skills. There is also the British Columbia’s Aboriginal Mine Training Association program, designed to prepare future workers for a given mine.[100] According to the Honourable Peter Taptuna, Minister of Economic Development and Transportation at the Government of Nunavut, ”the three territories have cooperated on the northern minerals workforce development strategy [...] we hope that the federal government will continue to lead in providing the needed funding to develop our human resources and prepare for new employment.”[101] On the subject of training, MiningWatch Canada’s Ramsey Hart told the Committee that the training deficit in the north remains a major challenge that needs to be overcome.[102] John Gingerich, President and Chief Executive Officer of Advanced Explorations Inc., stated that “much more training has to be done [in order to] bring more [...] indigenous peoples, the Inuit, into the workforce so that there is more participation in the wealth generation that comes from mining.”[103] A few witnesses commented on the end of federal funding for the Aboriginal Skills Employment Program (ASEP). According to Pamela Schwann, “programs such as the Aboriginal Skills Employment Program (ASEP) have been very beneficial in the past, as has the national sector council's Mining Industry Human Resources Council; [however], both of these programs are being wound down, or [their] funding has been significantly reduced.”[104] Pierre Gratton reiterated her praise of ASEP, stating that it has been “the most successful Aboriginal-focused training initiative in the country.”[105] Hilary Jones stated that the rate of participation in mining by the local population would decline if the program-funded training society no longer existed.[106] Peter Tapatai emphasized the importance of an early start in training and development of the region’s workforce to ensure that the Inuit can fully participate in the new economy.[107] For him, “training is not only important for the resource industry,” but also for the city and business workers. He explained that “high-paying mine jobs make it difficult for hamlets and local business to keep staff.”[108] Ginger Gibson MacDonald agreed that Aboriginal workers “need to be rewarded with education in the areas they want to be educated in, not just haul-truck drivers...they need to be...the journeymen in their communities after the mines are gone.”[109] Speaking of the Yukon, Claire Derome, President of the Yukon Chamber of Mines, highlighted the importance of fostering research institutions in northern Canada. “Bringing faculties and researchers to the North offers the opportunity to have higher education in very specialized and specific programs. It offers people the opportunity to work in the industry — not only in mining, but in all aspects of the industry in the Yukon — and to benefit from further specialization and from moving up in the labour force from being an operator to the management level.”[110] It also provides an opportunity for the youth to pursue higher education without leaving the North, thereby building professional capacity. According to Sandy Babcock, “... [creating a university in the North] would be extremely helpful in keeping our children here in the territory.”[111] Youth education has been raised as an important issue by several witnesses. Children should be informed of job opportunities that exist in the region through career counselling before they reach the college level.[112] Gordon Macdonald pointed out that while mine training societies and apprenticeship programs proved to be successful, stay-in-school programs, designed to help kids graduate with at least a grade 10 education, are critical for Aboriginal employment and capacity building.[113] Speaking of the Hamlet of Rankin Inlet, Pujjut Kusugak told the Committee that there is a 75% dropout rate and the community sees only about 30 to 40 graduates a year.[114] He added that the education system style is culturally different and that “[...] there was a lot of observation taught and hands-on education. For my parents' and Mr. Tapatai's generation, that was the mode of education. Now it's turning into a very southern style, where you're sitting in a classroom. It's very structured. It's almost a conflicting style of education, which really does contribute to the difficulty and stresses at home and just on the students themselves.” Similarly, Peter Tapatai told the Committee that “[...] Inuit are capable of working very well with their hands, and maybe more vocational-type classes can be put into schools [...] There is a big difference in percentage in people who will take academic...probably a bigger portion will be doing vocational [...] But there is no money allocated for those things. I think those things are very valuable. Academics seem to be pushed in schools. As Pujjuut Kusugak said, we're not all going to be doctors and lawyers; some are going towards a vocational end, and we should have home-grown vocational right in the high schools.” There are also other social issues that affect community capacity building and development. Ginger Gibson MacDonald raised this particular point when she spoke about very high levels of unemployment among Aboriginal people. She told the Committee that there are numerous barriers to employment that need to be addressed. “Criminal records and pardons are a big barrier in the north. People don't know they have access to pardons or are simply unable to get rid of the past, barriers of addictions, social traumas that are in place. We haven't tackled the issues associated with families well enough”.[115] C. Infrastructure1. Physical InfrastructureResource development in northern Canada faces major challenges with regard to infrastructure. According to Tara Christie, Senior Advisor at Newmont Mining Corporation, infrastructure issues in the north are wide-ranging, including aging and inefficient community power plants, limited broadband, short, unpaved airstrips, and underdeveloped services at industrial sites.[116] Glen Sibbeston told the Committee that many communities are not served by all-season roads, as most roads end shortly north of 60 degrees. “The Yukon has the best developed road network, the Northwest Territories less so, and Nunavut does not enjoy the benefit of a single highway.”[117] Peter Tapatai confirmed that a lack of transport infrastructure in Nunavut raises the cost of a mine. Compared to the Yukon where start-up costs are around $200 million, mines in Nunavut cost between $1.5 billion and $1.6 billion because companies need to build supporting infrastructure, including roads, rail and ports.[118] According to Glen Sibbeston, in approximate terms, transportation costs exceed $1000 per tonne to move goods to and from locations within 100 kilometres of a highway, and may reach $5,000 per tonne to move goods to sites 300 kilometres from a highway. Furthermore, for destinations served by large runways, goods can be moved for about $2 per kilometre, compared to $10 per kilometre in cases where smaller bush planes are necessary, and $20 per kilometre in more rugged destinations where a helicopter would be required to transfer goods.[119] Lack of transportation infrastructure and the harsh climate conditions of the north present additional challenges to moving equipment that is needed for development.[120] In general, resource development in northern Canada faces a cost disadvantage compared to other regions in the country due to the north’s rugged environment and infrastructure shortage. According to Pamela Schwann, the inadequacy of infrastructure in northern regions “affects the competitiveness of the mining sector, [as well as] the ability of northerners to effectively participate in employment and economic development opportunities related to mining.”[121] Honourable Peter Taptuna agreed by saying that “the lack of infrastructure in Nunavut affects the viability of mining projects and can needlessly delay projects. This applies to different parts of a mine’s life cycle.”[122] MiningWatch Canada’s Ramsey Hart offered a cautionary tale on infrastructure investment, citing Ontario’s Ring of Fire, where there is massive mineral potential in an area that has very little infrastructure. He told the Committee that the Mattawa and Muskkegowuk First Nations are supportive of development but recognize the impact of infrastructure such as roads and hydro may have on their culture and environment.[123] Peter Jenkins, Mayor of the City of Dawson, told the Committee that “the Government of Canada has an important role to play in developing strategic transportation infrastructure in the north.” [124] He noted that the Alaska-Canada rail link would effectively move northern resources from various development sites to tidewater export positions. While the rail-link would cost about $11 billion, it would lead to an additional economic output in GDP of $170 billion and create 25,000 new jobs. He also suggested that the government consider extending the Dempster Highway, and developing a deepwater port at King Point on Yukon’s north shore in the Beaufort Sea.[125] Sandy Babcock agreed that port access in the north would offer significant benefits to the resource extraction industry.[126] 2. Energy InfrastructureThe availability of energy resources required for mining operations is another major challenge to resource development in northern Canada, according to some witnesses. Peter Jenkins told the Committee that “the development of affordable energy is the biggest single impediment to developing the north’s economy.”[127] Figure 5, provided by Francis Bradley, Vice-President of Policy Development in the Canadian Electricity Association, shows that in 2011, hydro accounted for the majority of power generation in the Yukon and a significant portion in the Northwest Territories. Meanwhile, Nunavut’s power is derived almost exclusively from diesel.[128] Figure 5: Electricity Generation in Northern Canada, 2011

Source: Canadian Electricity Association, Brief presented to the Committee, June 5, 2012. Despite the recent investments in energy infrastructure, the Yukon is nearing the upper limits of its hydro capacity partly because of the conversion from fossil fuels to electric heating. According to Peter Jenkins, “Yukon's total current capacity is 129.6 megawatts, with 76.7 megawatts being generated from hydro facilities.” To put things in perspective, the Casino mine alone would require 100 megawatts, and the Selwyn and Mactung mines on the eastern border would require an additional 33 to 45 megawatts.[129] Peter Jenkins also told the Committee that there are a number of potential hydro sites that could be developed to provide affordable energy to the mining industry; however, more investment from different levels of government and the private sector is needed.[130] Peter Mackey, President and Chief Executive Officer of Qulliq Energy Corporation, explained that “electricity generation in the north has traditionally relied on diesel generation,” however due to the increasing costs of fossil fuels, “diesel generation in the long term will not be economical or sustainable.”[131] According to Robin Goad, President of Fortune Minerals Limited, the cost of diesel-powered generation in the Northwest Territories is between $0.20 and $0.30/kWh: five times the cost of electricity in the south.[132] Unlike southern regions, fuel oil and diesel must be shipped by truck or boat to mining sites, where generators are used to produce electricity. This has resulted in Nunavut having the highest power rates in Canada.[133] Because of the high costs of fossil fuels, mining companies have been considering alternative energy sources, such as wind power, in order to generate the electricity required for mining operations.[134] For example, the Diavik diamond mine in the Northwest Territories is in the process of building a 9.2 megawatt wind farm to mitigate the rising cost of fuel.[135] The Government of Northwest Territories is also making substantial investments in biomass, geothermal solar and wind.[136] The Minister of Environment and Natural Resources of the Northwest Territories Government, Michael Miltenberger, told the Committee that “we see these [technologies] as critical developments that are going to allow us to in fact have a sustainable cost of living in the north...”[137] However, Peter Mackey cautioned that the distance involved and the environmental conditions in which these technologies need to be installed add to their overall cost, making them economically less attractive.[138] Nonetheless, Brennain Lloyd noted that there is untapped potential of co-generation technologies to capture energy from waste heat. She also suggested that there is a role for the federal government, in consultation and cooperation with other levels of government, to work on issues such as energy distribution networks.[139] While Francis Bradley agreed that energy generation from renewable sources is important, he noted that they are “not well suited to support major resource development projects that require larger and more dependable capacity.”[140] To meet this capacity, “a new and expanded electricity infrastructure will be required.”[141] He also added that “the barriers to this infrastructure renewal are magnified for projects in the north, particularly in terms of cost, and most importantly social license, [especially from aboriginal communities].”[142] With respect to other potential energy sources, some witnesses presented on the recent development trends in nuclear power. In particular, there has been increasing global activity in the development of small modular reactors (SMR) technology. As noted by Michael Binder, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, the U.S. Department of Energy has allocated $450 million to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to support the licensing of American-made reactors, and to prove that the technology is viable.[143] According to Christofer Mowry, President of Babcock and Wilcox mPower Inc., Babcock and Wilcox Ltd., small reactors are 15% the size of a standard, large 1,000-megawatt plant, giving them an advantage in terms of siting flexibility.[144] He also added that “SMRs directly address the key challenges associated with the construction of large nuclear plants, including financial risks, cost and time uncertainty, production bottlenecks, and expensive power grid upgrades.” He told the Committee that SMRs can help various regions across Canada eliminate coal-powered generation, and at the same time allow them to meet the expected growth in energy demand.[145] Similarly, Peter Jenkins indicated that nuclear power presents an opportunity to meet growing demand for energy, and provides an alternative to fossil fuels.[146] However, as pointed out by Christofer Mowry, there are two key challenges to the deployment of SMR technology: the current nuclear liability regime; and the process for conducting environmental assessments for nuclear.[147] To align Canada with international standards, he recommended prompt ratification of the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage, known as the CSC. This would “attract international contractors for power reactor life extension and new build projects.” It would also “drive further Canadian nuclear exports, [...] helping to preserve Canadian nuclear jobs and infrastructure.” In terms of the environmental assessment for nuclear projects, he said that “while we are fully supportive of a robust and throughout environmental assessment, it’s imperative that the process be predictable and provide value.”[148] On the subject of the environmental and human safety of nuclear energy, including small nuclear reactors, Michael Binder told the Committee that the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission is responsible for ensuring that licensed nuclear projects are safe for the environment and the public. “Our regime includes annual inspections and reporting on compliances. Licensees also have to provide financial guarantees up front, which ensure that they have the required financial resources to properly clean up the site when they terminate their mining operations.”[149] He also explained that after the nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan, the nuclear industry worldwide is working to enhance safety measures and disaster mitigation strategies in order to be adequately prepared for a hypothetical “doomsday scenario.”[150] Christofer Mowry added that “today’s North America reactors operate at a remarkable level of safety, making the U.S. and Canada global leaders in nuclear safety and security [...] SMR design features result in a reactor that will be two to three orders of magnitude safer than the current U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission requirements mandate.”[151] 3. Community Infrastructure & CapacitySeveral witnesses have expressed concerns regarding community capacity and aging infrastructure. Growth in the resource development sector is adding significant pressure on northern communities’ services and infrastructure including airports, communications, power generation and health care.[152] According to Sandy Babcock, “the resource sector places heavy demands on transportation and energy infrastructure, broadband width, and labour markets.”[153] Melissa Blake, Mayor of Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo, stated that the capacity of her municipality has not kept pace with the fast development of the oil sands and as a result, faces increasing challenges in “access to land, transportation, and labour supply.”[154] She added that “while [the municipality] appreciates the recent budget announcements for expedited processing for temporary workers, it would be an immense asset if we not only had customs at our airport but also if there were immigration officials directly in Fort McMurray for visa processing and other related issues. This is not only of benefit to our labour force, but it helps with our goal to create a welcoming and inclusive community.”[155] She also expressed concern regarding the discontinued federal funding for the operations of Fort Chipewyan Airport.[156] Several witnesses stated that assistance from the federal government is needed to help replace aging infrastructure, and build new infrastructure so that northern communities can meet increasing demand for services driven by industry growth.[157] As pointed out by Peter Mackey, “the greatest challenge we have is operating with limited funds in the face of a growing population, a growing economy, and an aging infrastructure.”[158] Ginger Gibson MacDonald told the Committee that “workers need housing that’s reliable, adequate, affordable, and healthy...housing is tightly linked to health status...” Homes with mould and mildew lead to “chronic respiratory infections and debilitating health outcomes.”[159] Pujjuut Kusugak, Mayor of Rankin Inlet Hamlet, stressed the importance of dealing with the housing shortage: Homes are desperately needed. I'm sure that everybody here is aware of that. This causes overcrowded housing, which causes many health and well-being issues. This then stresses the health care system. We need more doctors. We have a hospital in Rankin and in Iqaluit, but again, there's a shortage of doctors and nurses.[160] D. Environmental Considerations and Sustainable DevelopmentThe Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) is not usually involved in mining projects in the Canadian territories. According to Helen Cutts, from the CEAA, environmental assessment regimes north of 60 degrees depend on “particular arrangements through comprehensive [land] claims.” In the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut, individual boards are typically established according to these land claims, and CEAA has “virtually no involvement”. However, in some cases, typically when trans-boundary considerations are involved, a project may be referred to the federal Minister of the Environment.[161] Similarly, Patsy Thompson, Director General of Environmental and Radiation Protection Assessment at the CNSC, mentioned that the role of CNSC in regulating nuclear projects in the territories would be to support the territorial boards by providing scientific and technical support for all aspects of the environmental assessment, and coordinating the scientific support with other federal government agencies like Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO).[162] A number of witnesses have expressed environmental concerns regarding mining activities in northern Canada. According to Ugo Lapointe, “one of the concerns rightly expressed by the population concerns the long-term management of mine tailings”.[163] In the case of metal mines, contaminants or toxic elements (e.g., heavy metals) are often released, presenting risks such as acidification or acid mining drainage. In the case of uranium mines, radioactive releases (e.g., thorium and radium) present additional challenges to managing mine tailings.[164] Brennain Lloyd, Project Coordinator with Northwatch, stated that “the disturbance from mineral exploration can be quite extreme, with a complete removal of vegetation and a total loss of ecological function at the site level.”[165] Large, low-grade, open mines are often in close proximity to existing communities, particularly in northern Quebec. The impacts of these mines on the natural environment, including the noise and dust they produce, can be a nuisance to local inhabitants.[166] With respect to such issues, Anil Arora of NRCan told the Committee that NRCan “[reviews] technical documentation and [provides] scientific and technical expertise in the areas of minerals and metals sciences, including expertise related to things such as acid rock drainage, waste management, mine effluent, and metal leaching.” He added that NRCan’s goal is to “ensure responsible development that reduces environmental impacts and maximizes benefits to communities and all Canadians.”[167] Pamela Schwann, from the Saskatchewan Mining Association, stated that, when considering the impacts of mining, “we also have to put things into a global context, in that there is a need for resources on a global basis, and Canadian mining companies operating in Canada under quite stringent environmental regulations operate responsibly.” According to her, it is preferable “to have the resources developed in Canada rather than elsewhere.”[168] Similarly, David Kilgour noted that “today’s Canadian mining industry has changed dramatically from the practices of the past and operates in a manner that is sensitive to the environment and to its local host communities.”[169] Jody Kuzenko, General Manager of Base Metals, North Atlantic Region, Vale, told the Committee that “environmental responsibility is a competitive advantage, and in this day and age, as we’re developing the next generation of miners, it is critically important to recruitment and retention.”[170] According to Brennain Lloyd, contemporary discussions of sustainable development include “not just impacts on the environment; but [are] often cast in the context of community sustainability,” including local aspects such as food, energy, and other aspects of socioeconomic stability.[171] In Quebec, the Quebec Mining Association recently signed an agreement with the Bureau de normalisation du Québec to measure the mining sector’s progress in “incorporating sustainable development principles into the daily operations of [member] companies [of the Association].”[172] MiningWatch Canada’s Ramsey Hart stated that “most communities we work with [...] are looking at mining with optimism and welcoming arms for the economic opportunities it can advance. However, no one wants mining to be forced on them or, as Chief Gagnon said [...] to be shoved down their throats. So it's important that we have processes in place to engage communities, to ensure adequate review of proposed projects, and to effectively have participation in the review of projects”.[173] Eberhard Scherkus also stated that, in Nunavut, “we've had great community support from the councils, the peoples, and the businesses; the communities are unified in their support of resource development”.[174] The Honourable Michael Miltenberger stated that “as we go forward we are very concerned about the balance of resource development and environment. We are open for business. We want to do it in a sustainable way.”[175] According to some witnesses, a national energy strategy is critically important to the sustainable development of the north. Peter Jenkins stated that “it must develop a national energy strategy in cooperation with the provinces and territories that will support federal investment in environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable infrastructure.”[176] Martin von Mirbach, Director of the Canadian Arctic Program at the World Wildlife Fund, also asserted that “we have an opportunity in Canada to develop a truly visionary Canadian energy strategy, charting a course for Canada that is aligned with the country’s climate change commitments […] Opening up new frontiers for oil and gas development without a long-term energy plan that tackles CO2 emissions risks pushing us further from our national goals and international responsibilities.”[177] On the subject of offshore oil development, Martin von Mirbach noted that “there is currently insufficient knowledge and inadequate technology and infrastructure to safely carry out drilling in Canadian Arctic [....] there’s no oil spill response capacity to address a sizeable well blowout or large scale spill in Arctic waters.” The lack of infrastructure is a big challenge in addressing an oil spill in the Arctic. The presence of ice adds significant complexity to containing the spill, making it very difficult to clean up an oil spill. More time, research and large-scale planning is needed to address these gaps and to ensure sustainable development in the Arctic.[178] Martin von Mirbach also proposed cumulative environmental assessments in the region to set overall thresholds and identify areas where it is appropriate to carry out activity and areas where it is not. He also said that the NEB should be responsible for modelling the trajectory of possible oil spills.[179] Mimi Fortier told the Committee that “a great deal of research on ice-infested waters and ice-covered waters has gone on over decades.” Furthermore, “the National Energy Board expanded an existing study to conduct a public review of offshore drilling requirements.” In its recent report, the Board confirmed that its regulatory regime “can address matters related to safety of northerners, workers, and the environment.”[180] THE “RING OF FIRE”: A CASE STUDYAs part of its study on the development of natural resources in northern Canada, the Committee devoted two meetings to hearing witnesses specifically on the development of a whole new region of northern Ontario known as the “Ring of Fire”. Located in a remote and under-developed area, the Ring of Fire represents a singular and challenging case in itself. The Ring of Fire area stands in the James Bay Lowlands of northern Ontario, approximately 1,000 kilometres northwest of Toronto (Figure 6). Mineral exploration in the area began in 2002 and initially led to the discovery of copper and zinc deposits. In 2008, a large chromite deposit was found. Chromite is used primarily to make an alloy, ferrochrome, a component of stainless steel. Although the chromite discoveries in the Ring of Fire may someday rank amongst the largest in the world, the chromite market is presently tight, most of it currently being consumed in Asia.[181] A. Developing The Ring of Fire depositsAfter the acquisition of Freewest Resources and Spider Resources in 2010, Cliffs Natural Resources “began studying the proposed chromite project in the Ring of Fire”.[182] Cliffs’ project has four components:

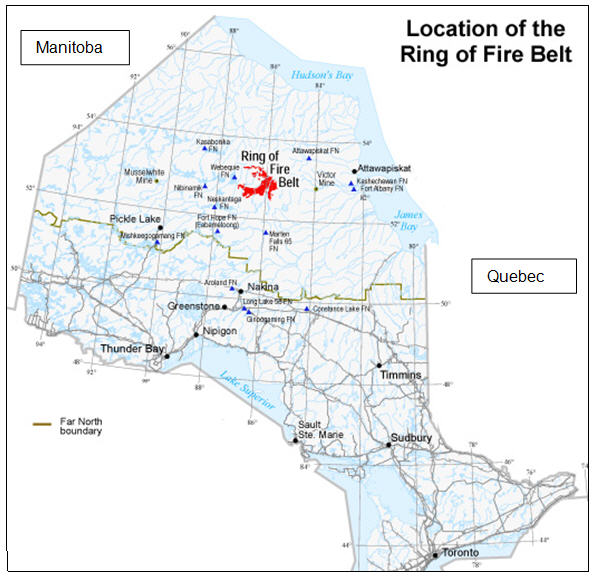

The company envisages exporting approximately 40% of its on-site production, arguing that being “able to sell into the global market for chromite concentrate is key to being able to build a mine”.[183] In fact, the development of the Ring of Fire area will depend to a great extent on global market conditions, knowing that the market for chromite and ferrochrome is extremely volatile and closely related to the Chinese demand.[184] According to William Boor, Cliffs’ overall project represents a potential investment of approximately $3.5 billion, the creation of over 1,100 permanent jobs, an equal number of construction jobs, and 2,000 to 3,000 indirect jobs.[185] Figure 6 — Location of the Ring of Fire

Source: Ontario Business Report, Ring of Fire lights up Northern Ontario’s mining industry, http://ontariobusinessreport.com/en/economic/articles/economic_article_27.asp. The achievement of Cliffs Natural Resources’ project is also key to further developing the Ring of Fire. As pointed out by Ronald Coombes, Cliffs “has a deposit with the economic size to support initial infrastructure costs, which will allow other smaller mines to be economical”.[186] This would likely be the case of projects being undertaken by Noront and White Tiger to develop their nickel and iron deposits in a few years from now, once the Ring of Fire is more accessible and has the proper infrastructure to do so. Noront’s approach would be to mine its Eagle’s Nest nickel ore first, which would offer a greater return on investment, and then look at supplying the North American market from its Blackbird chromite deposit, it being “a better fit for the company's size”.[187] White Tiger Mining Corporation owns the Norton Lake property where it is contemplating the development of its nickel, copper, cobalt, and PGM (Platinum Group Metals) deposit once the proposed north-south road corridor is approved.[188] Many other opportunities could evolve from the future construction of the road along the proposed corridor. B. The Ring of Fire: unprecedented challenges for unprecedented opportunitiesWhile recognizing the immense mining potential buried underground in the Ring of Fire, all witnesses heard by the Committee stressed that this mining potential could hardly materialize without overcoming unprecedented challenges. These challenges are quite similar to those identified for resource development north of 60, but they are magnified in all aspects when transposed in the context of northern Ontario’s Ring of Fire. They include: ecosystem sensitivity; remoteness and lack of infrastructure; consultation with First Nations; and, education and training.[189] 1. Ecosystem SensitivityThe Ring of Fire is located in the James Bay Lowlands, a large wetland area. The region is poorly drained, dominated by marsh, string bogs and muskeg, and is dissected by slow-flowing rivers draining into Hudson’s Bay and James Bay.[190] Mine exploration and development, as well as building the required infrastructure in such a fragile and pristine environment will require comprehensive planning and consultation with First Nations. New infrastructure will have to be carefully planned in order to minimize the impacts on fish, wildlife, and plants on which local communities rely. In fact, “new roads and infrastructure corridors, including a proposed slurry pipeline, will fragment the habitat of migratory animals — caribou, moose, etc. — and disrupt their travel routes. [...] Fuel and chemicals required by the mines present major environmental concerns [and] waste rock and tailings from the mines have the potential to release harmful chemicals to the environment and will remain on the land long after the mines are closed.”[191] First Nations communities expect these important issues to be fully addressed through a thorough and comprehensive environmental assessment process.[192] 2. Remoteness and Lack of InfrastructureThe population of the Ring of Fire region includes small, isolated First Nations communities established along the suture line between the lowlands and the drier Canadian Shield, and the Hudson Bay and James Bay coast. The remote location of the Ring of Fire explains why exploration costs are “at least ten times than the costs in Sudbury” and why it “is not attractive to many professionals”.[193] Moreover, the total absence of infrastructure represents the first and foremost impediment to resource development in the area. Witnesses from the mining sector appearing before the Committee stressed that transportation infrastructure remains a priority if the region is ever to develop. Many corridor openings have been proposed: