FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

IMPROVING THE ECONOMIC PROSPECTS OF CANADIAN GIRLSINTRODUCTIONThe Standing Committee on the Status of Women agreed in February 2012 to study “the prospects for Canadian girls with regards to economic prosperity, economic participation and economic leadership, and what changes can be made by Status of Women Canada to its approach to dealing with them.” On June 9, 2012, Status of Women Canada announced that its theme for Women’s History Month in 2012, celebrated in October of each year, would be “Strong Girls, Strong Canada: Leaders from the Start.”[1] The Agency also announced that it would receive funding applications for its Call For Proposals entitled “Setting the Stage for Girls and Women to Succeed,” under two themes: “strengthening girls’ and young women’s economic prosperity,” and “engaging girls and young women in leadership roles.” The deadline for such applications was August 10, 2012. Starting on February 29, 2012, the Committee was briefed by Status of Women Canada officials over two hearings, heard comments from the Honourable Rona Ambrose, Minister for Status of Women, during her appearance before the Committee on March 14, 2012, and heard testimony from 40 individual witnesses from 34 different organizations, companies or institutions. In addition, the Committee received briefs from 10 organizations, many of which had appeared before the Committee, along with written speaking notes and responses to follow-up questions submitted by Committee members. This report summarizes evidence with respect to economic prospects for Canadian girls under the headings of participation, prosperity and leadership, following an opening section on themes that crossed each of those topics, and makes recommendations to Status of Women Canada to support improved prospects for Canadian girls. Witnesses offered some broader recommendations that they believed would improve the situation for women and families in Canada, and thereby would improve the economic prospects of Canadian girls. However, in keeping with the motion defining this study, the Committee has made only those recommendations (1) that could be implemented or initiated by Status of Women Canada and (2) that focus specifically on the situation of girls. STATUS OF WOMEN CANADAAs noted above, the Committee first learned about the activities of Status of Women Canada, an agency that administratively reports through Canadian Heritage, but has its own Minister, the Honourable Rona Ambrose. In its 2010-2011 Report on Plans and Priorities, Status of Women Canada identified the strategic priority for its Women’s Program[2] as “equality for women and their full participation in the economic, social and democratic life of Canada.”[3] A. The Women’s ProgramOf $30.8 million anticipated in expenditures for that fiscal year, $19.9 million was to be allocated to grants and contributions to women’s organizations through the Women’s Program.[4] A central focus of the program is on “improving women’s and girls’ economic security and prosperity.”[5] A complete list of projects funded by Status of Women Canada, related to girls’ economic well-being, was provided by the Agency and is attached as Appendix A of this report. B. International Day of the GirlAs described by Status of Women Canada on its Web page, Canada has been a leader in the international community in its adoption of the United Nations declaration of October 11, 2012 as the first International Day of the Girl Child.[6] The Minister responsible for the Status of Women has played a leadership role in this initiative. In her own words, In March [2011], I proposed to Parliament a motion to proclaim an International Day of the Girl — and the motion received unanimous consent from all parties. On behalf of Canada, I led the call for an International Day of the Girl at the United Nations. We met with many delegations who were very supportive and so we drafted a resolution that has been co-sponsored by 104 countries! The resolution was adopted by the Third Committee of the United Nations General Assembly on Monday November 15th, 2011, and on December 19th, 2011, they formally adopted October 11th as the International Day of the Girl Child.[7] The Agency’s Website addresses Canada’s role, and indicates that the International Day of the Girl is an opportunity “to raise awareness about the particular challenges that girls face and to take action.”[8] OVER-ARCHING THEMESThe Committee’s deliberations focused on the three specific themes included in the motion triggering this study. A range of witnesses spoke to more than one of these elements, and many of their messages applied to all three. These themes are outlined below as they underpin the recommendations of many witnesses and lay the foundation for more specific proposals under the three areas of study. A. Gender StereotypingThe Committee heard that social expectations of girls and young women in many communities within Canada are less than the expectations of boys. When parents, teachers, the media, employers and others communicate a more constrained future for girls, the prophecy can become self-fulfilling. Some witnesses focused on the role of schools in promoting gender equality in content and methods,[9] with one explicit recommendation to “review and address gaps in the school curriculum to ensure that gender equality is incorporated at every level of education.”[10] Other testimony focused on the role of schools in promoting less traditional fields of study and career opportunities for girls, and in reducing gender-based violence and harassment, each addressed in greater detail later in this report. 1. Role of BoysCommittee members and witnesses alike articulated the need to engage boys in changing these negative and limiting views of girls, particularly as these boys and girls will grow up to become Canada’s future work force and leaders.[11] Other witnesses, recognizing the value of engaging boys in a critical analysis of expectations for males and females, also cautioned against diluting female-targeted programs, as addressed in greater detail below. They also advised against pitting the situations of girls and boys against each other.[12] Other witnesses identified the particular need to engage boys in anti-violence programs, addressed in greater detail later in this report. B. Education and TrainingThere was broad agreement among witnesses that education is pivotal to increasing economic opportunities for girls. While recognizing that education from Kindergarten to Grade 12 (K-12) is a provincial responsibility, except on-reserve, several witnesses highlighted the importance of these levels of education. The Committee heard that girls are generally performing better than boys in the K-12 years, and are graduating in higher numbers. However, witnesses also pointed out that the economic prospects for boys who did not complete K-12 were often better than for girls in the same situation, pointing to higher paying opportunities for boys without a high school diploma than for girls.[13] The Committee also learned of the higher non-completion rate for Aboriginal girls, addressed in greater detail in a later section of the report, with associated recommendations to focus on high-school completion and on-going access to education and training for these girls to improve their economic prospects.[14] A similar recommendation was made with respect to both high school completion and literacy programs for women with experience in the criminal justice system.[15] Witnesses also identified specific gaps in school curricula that, if filled, would increase the economic prospects for Canadian girls. These include promotion of the non-traditional fields of study and careers — science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and the skilled trades; financial literacy; and violence-reduction programs. Each of these is addressed in greater detail in later sections of this report. More general recommendations called on the federal government to make education for girls a priority, especially those in marginalized groups.[16] Other witnesses highlighted the need for Canada to modernize its K-12 curriculum. Tracy Redies, President and Chief Executive Officer, Coast Capital Savings Credit Union, told the Committee: ...our education system, which should offer the perfect opportunity for young women to learn and think globally, is too narrow in its focus. If we are to prepare Canadian youth to capitalize on the new global realities, our curricula will have to change to reflect those realities.[17] Linda Hasenfratz, Chief Executive Officer, Linamar Corporation, told the Committee of her vision for Canada’s education system, to enhance the opportunities for girls: I would love to see us in Canada setting a goal to be the best in the world in terms of an education system that's going to create the smartest, the most innovative, and the most successful scientists and engineers in the world, with the highest percentage of female grads.[18] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada, working through its federal/provincial/territorial relationships, encourage provincial and territorial officials responsible for education to continue to ensure that curricula reflect current and emerging global economic realities. 1. Access to Post-secondary EducationResearch has demonstrated repeatedly the links between education and economic participation and prosperity in Canada, and indeed internationally. As shown in Figure 1, Canadian data demonstrate that full-time employment for those without a high school education has always been lower than with any kind of post-secondary education, and has been declining steadily since 1997. Conversely, the full-time employment of post-secondary graduates has increased steadily over time. Figure 1 – Full-Time Employment by Educational Attainment

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM table 282-0003, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/12-581-x/2010000/edu-eng.htm. The ability to pursue a post-secondary education can impact the future income of young Canadians, as post-secondary education is now a prerequisite for approximately 70% of newly listed jobs. This as youths aged 15 to 24 are experiencing an unemployment rate which is nearly double the unemployment rate for all Canadians, at 13.9% compared to 7.2%,[19] post-secondary education is especially important. Recent data from Statistics Canada also indicate that: ...more girls than boys earn their high school diploma within the expected timeframe and girls are less likely to drop out. More women than men enrol in college and university programs after completing their high school education. A greater percentage of women leave these programs with a diploma or degree.[20] In international rankings, Canada placed first among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries for the graduation rate at upper secondary level for both boys and girls, though girls had even higher graduation rates.[21] Looking beyond high school, the 2006 Census reported that more than 60% of females in Canada have some post‑secondary education, with more than 20% having completed at least an undergraduate degree at a university.[22] The Committee heard from witnesses about the high returns from receipt of a post-secondary education, especially for girls and young women, and the role of costs and anticipated debt as obstacles to both enrolment and post-studies economic well-being.[23] Related recommendations focused on federal (and provincial) student debt reduction.[24] Carol Stephenson, Dean, Richard Ivey School of Business, University of Western Ontario, told the Committee of the benefits of offering scholarships for women: Scholarships for women is another area [where government can act]... I think that is a great incentive for women — and especially those who have affordability issues — to go on and pursue a business career, which is probably what I'm the most familiar with.[25] In addition, witnesses drew attention to particular groups that are often excluded from these opportunities, including youth coming out of child welfare systems,[26] girls from rural or remote communities,[27] girls with disabilities,[28] and Aboriginal girls.[29] Recommendations targeted to these groups included improving accessible transportation to support disabled students in post-secondary education,[30] and sustaining or improving funding for post-secondary education for Aboriginal students.[31] C. Family RolesMany witnesses described the role unique to girls and young women in mothering, particularly pregnancy and infant care, and in their families and communities more broadly. Witnesses also provided evidence of the very high participation rates of mothers in the labour force, including the 70% of mothers, with children under the age of five, who work outside their homes.[32] With respect to employment, Statistics Canada data show that for girls and women between the ages of 15 and 24, the unemployment rate (for those not working and looking for work) is 11.8% for those without children, and 19.1% for those with children.[33] Child care and related supports were widely identified as necessary to permit and encourage the economic participation and prosperity of young women who are mothers, both through education and in the workforce.[34] Related recommendations with respect to child care focused on federal funding programs for early childhood learning programs.[35] More specifically, witnesses spoke of particular needs for childcare for women working in the trades, where work often extends beyond the “normal” workday,[36] and for First Nations women both on reserve and in urban settings.[37] One international study concluded that the provision of affordable child care can increase the labour force participation of mothers of young children, increasing their economic prosperity and well-being: Employed parents with young children cannot retain their jobs without some form of childcare. Although mothers used to enable fathers’ employment by caring for their children at home, more mothers are now employed in Canada and the other liberal states. Research has found that reducing childcare costs increases maternal employment.[38] In addition to care for young children, witnesses, from organized labour and from corporate leadership, identified other challenges to balancing work and family life, and their impact on economic participation, prosperity and leadership.[39] Recommendations were varied, and included a call to the government to lead a campaign to promote such balance[40] and to create labour policies that encourage increased balance,[41] along with a suggestion that involving fathers in domestic activities be promoted to help create better balance.[42] Finally, Ellen Moore, Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer, Chubb Insurance Company of Canada pointed out the need for reintegration of female employees after longer absences, like maternity leave, calling on employers to support “on-ramping women after a career absence.”[43] PARTICIPATIONThe Committee’s motion identified economic participation as one of the goals for girls and young women. Among the witnesses, many identified the importance of employment to economic well-being and the foundation upon which economic prosperity and leadership could be built. Evidence and recommendations on this more general theme follow the section on barriers to such participation facing some girls and young women. A. Barriers to ParticipationIn addition to the general themes identified in the previous section of this report, witnesses identified obstacles that could prevent girls and young women from participating in the labour force. The Committee heard from Status of Women officials that the removal of barriers to participation in the economic, social and democratic life in Canada is a significant goal of its funding programs.[44] The Committee heard that girls growing up in already marginalized groups in Canada often face the greatest and most numerous obstacles.[45] As noted above, these groups include those with personal experiences of harassment and violence; those in rural and remote communities; people of Aboriginal status; newcomers to Canada; visible, ethnic and linguistic minorities; and those raised in and living in poverty.[46] For example, the Committee heard that the wage gap between men and women in Canada is wider for Aboriginal, disabled and racialized women than the Canadian average.[47] As these circumstances often intersect with one another, recommendations often addressed several of them together. For example, Barbara Byers, Executive Vice-President, Canadian Labour Congress, recommended recognizing and addressing “the disproportionate levels of poverty, unemployment, and violence among [A]boriginal women and women with disabilities.”[48] Leanne Nicolle, Director, Community Engagement, Plan International Canada Inc., recommended that Status of Women Canada could support the economic prospects of Canadian girls by “making sure that life skills training is offered to marginalized communities, such as the aboriginal community, and those who are living below the poverty line in priority neighbourhoods.”[49] Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond, Representative for Children and Youth, British Columbia told the Committee that in order to improve the prospects of Canadian girls, ...we need to pay particular attention to some deeply vulnerable groups of girls and women using the evidence that we know is available and to develop and innovate in terms of more effective approaches in our social policy and in our community development approaches so that we can adequately engage and support girls and women to have better outcomes.[50] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada continue to contribute to projects that address girls and young women who are multiply disadvantaged, and investigate ways to increase the number of projects with this focus. For those girls who manage to overcome these roadblocks, there are constraints that continue to undermine their economic participation and prosperity. A recent research report commissioned by the federal government sums up these continuing impacts: Financial pressures related to low wages, occupational instability or higher student debts and mortgages among youth today than in the past can then create a feeling of uncertainty about future prospects. Not all youth have access to the same portfolio of personal, social, educational and financial resources to successfully enter into adult society.[51] Evidence and recommendations more specific to each of the circumstances noted above follow. 1. Gender-based Harassment and ViolenceViolence has a severely negative impact on a woman’s economic prosperity, and a woman’s poor economic circumstances can put her at greater risk of violence. This cycle is explained in a publication by the Public Health Agency of Canada: Poverty marginalizes women, increasing their risk of victimization, while violence also isolates women, as the mental and physical effects grind away at women’s sense of well-being, limiting what is possible.[52] The same publication states that poverty and violence reflect unequal relationships of power, which result in the systemic discrimination against women, and “this systemic discrimination means that women are less likely to get well-paying jobs and to meet their needs for decent housing, education, child-care and health services.”[53] In addition, “the trauma of being abused can result in a multitude of physical and psychological impacts that affect women’s employability.”[54] The publication expands on the challenges with employability for these women: ...women who have experienced abuse can suffer from anxiety and depression; they may have difficulty concentrating or maintaining disciplined practice; and they may be suspicious or forgetful. It can take them more time to go through job-training programs than other women. They may have to work harder to build up their self-confidence and be more concerned about their safety.[55] A 2011 study reported in the journal Canadian Public Policy states: ...chronic mental and physical health problems associated with abuse may make women less employable, reducing their capacity to acquire economic and material resources to sustain themselves and their children, with impacts on absenteeism and work quality and subsequent losses to employers and the state.[56] The Committee heard from several witnesses that harassment and violence are clear obstacles to economic participation, prosperity and leadership for girls and young women in Canada.[57] The Minister, the Honourable Rona Ambrose described the relationship when she told the Committee: “We believe, of course, that women’s safety goes hand in hand with their economic security.”[58] The importance of this safety from harassment and violence often underpinned witnesses’ suggestions that “girls-only” spaces are important to their future economic prospects.[59] This and other aspects of single-gender services and initiatives, and related recommendations, are addressed in greater detail in later sections of this paper. Witnesses advised the Committee that the harassment rate of young women is as high as 46% for high-school aged women in Ontario,[60] and the sexual abuse rate among Aboriginal girls under the age of 18 was as high as 75%.[61] The Committee also heard that girls in rural and remote communities often have less access to services when they are experiencing violence.[62] As noted above, several witnesses discussed the importance of making schools safe from bullying, gender-based harassment and violence, and identified promising initiatives to achieve this goal. Such initiatives are included in Appendix B to this report, which lists initiatives described by witnesses during their testimony or by others in written submissions to the Committee. Describing the impact of gender harassment, Saman Ahsan, Executive Director, Girls Action Foundation, told the Committee that It causes depression; it causes low self-worth. It can lead to substance abuse, violent delinquency, thoughts of suicide. So it can create a lot of problems. A girl who is faced with this kind of harassment is obviously not going to do her best in her studies and in her professional career, and this is going to limit her economic prospects in the long term.[63] One of Ms. Ahsan’s recommendations was “implementing and expanding programs that reduce gender harassment, especially in educational institutions.”[64] Similarly, Jocelyne Michelle Coulibaly, Representative for the Ottawa Region, Board of Representatives, Fédération de la jeunesse franco-ontarienne told the Committee that “it is essential to expand and develop programs to reduce sexual harassment.”[65] In its presentation to the Committee, the Public Service Alliance of Canada recommended “effective action to protect girls from discrimination and harassment.”[66] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada sustain its support for programs that create safe spaces for girls, particularly with respect to preventing and addressing the violence they face in schools and in the workplace. As noted above, many witnesses also identified the need to engage boys in programs to prevent and address gender-based violence, and acknowledged the support provided by Status of Women Canada to this important element of its anti-violence work.[67] The Committee received recommendations that suggested a more general approach to preventing and responding to violence against girls and young women. For example, the YWCA, in a written submission to the Committee, recommended that “the federal government commit to leading a process to coordinate policies on violence against women at all three levels of government to ensure women’s safety.”[68] In another brief to the Committee, Jolanta Scott-Parker, Executive Director, Canadian Federation for Sexual Health recommended investments in “broadly based sexual health education” to promote healthy relationships.[69] In its presentation distributed to the Committee at the time of their appearance, the Public Service Alliance of Canada recommended programs to make girls aware of their rights and supports to exercising them,[70] a goal that formed part of the initiative by Plan Canada and the Minister responsible for the Status of Women to gain recognition of the International Day of the Girl.[71] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada support the safety of girls through:

The Committee also heard that escaping violence can leave women in precarious situations, leading to specific recommendations with respect to federal involvement in the provision of both emergency shelters[72] and longer term affordable and safe housing.[73] 2. Rural and Remote CommunitiesEvidence provided to the Committee included concerns about access to support services in rural and remote communities to help girls overcome barriers to economic participation, and about the extra challenges to achieving such participation and prosperity for girls in those communities.[74] The Committee heard from Status of Women officials that a recent call for proposals to address issues facing women in rural and remote communities resulted in almost 250 proposals, of which 48 had been announced; some addressed violence against women, while others addressed economic security, all particularly focused on women in smaller communities.[75] The announced projects are included in Appendix A. Among the most significant issue facing girls in these communities is the lack of educational programs and local job openings available to them, forcing them to leave home to access learning and employment opportunities.[76] For Aboriginal girls, witnesses described additional challenges related to a new culture and language,[77] child care,[78] and lack of affordable housing when they moved.[79] Jane Stinson, Director, FemNorthNet Project, Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women recommended that “the federal government support the establishment and expansion of post-secondary education in northern communities.”[80] She also explained the need for supporting young women when they have to leave their communities to pursue education: Young women in northern communities normally have to leave their communities and travel great distances to southern locations, where they are really cut off from family and friends and both emotional and financial support... it's also about aboriginal students moving to a community where the language is totally different and where there are very few supports.[81] Elyse Allan, President and Chief Executive Officer, GE Canada told the Committee: ...girls in remote communities who want to pursue post-secondary education must often leave home to do so. This can be costly and stressful, a big disincentive. Supporting community and post-secondary programs that support girls in their transition away from home, including provisions for child care, we believe well recommended.[82] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada work with Treasury Board to ensure that gender-based analysis within departments and agencies take into account policy impacts on women and girls in remote and isolated communities. 3. Aboriginal StatusAboriginal girls and young women make up a significant portion of the female Aboriginal population. In 2006, 28% of the Aboriginal females were under 15 years of age, and 18% were between 15 and 24 years of age.[83] In that same year, the median age of Aboriginal females was 27.7, compared with 40.5 years for non-Aboriginal females.[84] Statistics Canada also reports that Aboriginal women are generally less likely than non-Aboriginal women to be a part of the paid labour force. According to 2006 data: ...51.1% of Aboriginal women aged 15 and over were employed, compared with 57.7% of non-Aboriginal women. Aboriginal women were also less likely than their male counterparts, 51.1% versus 56.5%, to be employed.[85] Aboriginal girls are more likely to be faced with risk factors that could jeopardize their economic participation, prosperity and leadership into their adult lives. The Canadian Women’s Foundation reports that Aboriginal girls “experience alarmingly high levels of depression, suicide, addiction, HIV infection, and poverty.”[86] a. Early motheringResearch indicates that between four[87] and six[88] times as many teenaged First Nation girls are parents compared to their non-Aboriginal counterparts. The most recent data indicates that 8% of First Nation teenaged girls were parents, compared to 1.3% of non-Aboriginal girls the same age.[89] This, in turn, means that more Aboriginal girls are being raised by young mothers than their non-Aboriginal counterparts, with one in four Inuit and First Nation girls, and one in five Métis girls having mothers between the ages of 15 and 24, compared to fewer than one in ten non-Aboriginal girls.[90] This, of course, has repercussions on education and income for girls between the ages of 10 and 19, the focus of the Committee’s study. More than 33% of Aboriginal women over the age of 25 have not completed high school (compared to 20% for non-Aboriginal women); of those, almost 25% Aboriginal women aged 15 to 34 identified pregnancy or the need to care for children as their reasons for not completing school.[91] Similarly, 11% of Aboriginal women living off-reserve who had started but not completed post-secondary education gave the same reason for withdrawing from their studies.[92] However, recent data show an improvement in post-secondary attainment for Aboriginal women between the ages of 25 and 54, rising from 41% in 2001 to 47% in 2006.[93] b. Violence against Aboriginal womenThe Committee has extensive knowledge of the issues facing Aboriginal women with respect to violence and human trafficking, as these issues were highlighted in the Committee’s 2010-2011 study on violence against Aboriginal women, which resulted in an interim report, Call Into the Night: An Overview of Violence Against Aboriginal Women,[94] and a final report Ending Violence Against Aboriginal Women and Girls: Empowerment — A New Beginning.[95] c. Gender-based analysis in economic developmentIn 2007, the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) recommended the following to improve the economic opportunities for Aboriginal women: Ensure economic opportunities strategies consider all the socioeconomic conditions that are required to create the right environment for Aboriginal women to participate in the economy. For example, child care, adequate housing, strategies to combat gendered racism and ensuring that the right and fundamental freedom to live free from violence are all factors to be considered. Existing inequities facing Aboriginal women must be removed in all sectors.[96] In the hearings for this study, the Committee learned that an analysis of the federal framework for aboriginal development by the NWAC found that economic opportunities emerged primarily in sectors where men benefit, and that workshops with federal departments and agencies discussed how federal investments could increase Aboriginal women’s economic participation.[97] Claudette Dumont-Smith, Executive Director, NWAC, called on the federal government to: …conduct a cultural and gender-based analysis of [Aboriginal] community assets and developmental funding at the federal level to evaluate access and outcomes of funding; implement equitable and/or increase funding opportunities for [A]boriginal women in programs like the aboriginal business development program and aboriginal procurement strategy; and measure gender equity in a consistent manner and analyze data disaggregated by age and gender using a gender analysis method.[98] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada continue to work with appropriate federal departments and agencies with respect to encouraging the gender-based analysis of economic development programs, particularly those targeted to Aboriginal peoples and communities. d. Child welfareThe Committee heard of the significant overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in the foster care system.[99] According to the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect, the incidence rate of substantiated child maltreatment investigations was four times higher in Aboriginal child investigations than in non-Aboriginal child investigations.[100] Reports indicate that there are more First Nations children in the care of the child welfare system now than at the height of the residential school system.[101] Abuse and neglect and involvement in the child welfare system can have a direct impact on a child’s education and future economic success. Reports indicate a link between a child’s home environment and his/her academic performance and educational success.[102] According to a study by the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies, children in foster care in Ontario have a graduation rate from high school of 44%, compared to 81% for their peers.[103] Another report lists the serious consequences for children coming from neglectful or abusive homes:[104]

e. Criminal justiceIn addition, Aboriginal peoples remain overrepresented in correctional facilities, and this is the case for Aboriginal female youth: a Statistics Canada report indicates that in 2008/2009, “among the nine reporting provinces and territories, Aboriginal females [who are youth] accounted for 44% of admissions to open or secure custody, 34% of admissions to remand, and 31% of admissions or intakes to probation”.[105] Further, this study reported there is a significant link between youth in custody and limited economic prospects. When young women enter custody, they are less likely to have a high school diploma and more likely to be unemployed than women in the general Canadian population.[106] A University of Waterloo study on women leaving prisons and re-entering communities stated that employment is key to reintegration. It highlighted the marginalization and stigma that women feel when they leave prison, and the impact this can have on their confidence and motivation. The study also states that many women exiting prison did not have employment opportunities, and instead described “their impending need to find a job.” It stated that for the women, “the availability of employment that will afford them a living wage [would be] integral to preventing a return to substance abuse or other forms of criminal behaviour.”[107] Witnesses highlighted many of these issues: Aboriginal girls face low high school completion rates, much higher teen pregnancy and birth rates,[108] higher rates of involvement in the criminal justice system,[109] and higher poverty rates than their non-Aboriginal counterparts, each of which has negative impacts on their economic future. Specific recommendations related to these issues included a greater emphasis in Aboriginal communities on anti-violence campaigns,[110] and greater access to all health services for Aboriginal girls on-reserve.[111] f. Relocation for educationIn addition, witnesses indicated that even those Aboriginal students who do graduate from high school may not be equipped for post-secondary education. Paige Isaac, Coordinator, First People’s House at McGill University, explained to the Committee that transition programs offered by some universities for Aboriginal students may not help, “because some K-12 students are not being qualified to go into a university.”[112] In response, witnesses called for improved education opportunities for Aboriginal girls on-reserve. Elyse Allan told the Committee: “...Remote communities are on the front line of resource development, but frequently the people living in remote communities cannot participate in this development for want of skills, training and basic infrastructure.”[113] Andrée Côté, Women’s and Human Rights Officer, National Programs Section, Public Service Alliance of Canada echoed the importance of improving on-reserve school outcomes.[114] In particular, Paige Isaac recommended “a mandated improved [A]boriginal curriculum in K to 12.”[115] Ms. Allan went on to support recommendations that called for federal funding for on-reserve schools to equal that provided to off-reserve schools.[116] Angelina Weenie, Department Head, Professional Programs, First Nations University of Canada also flagged the funding differentials between on-reserve and off-reserve schools.[117] Ms. Isaac also highlighted the need for adequate funding for existing supports for Aboriginal students away from home, and recommended additional support to permit culturally appropriate counselling,[118] and identified as a priority “supporting pipeline projects... connecting with [A]boriginal people while they’re young and keeping that connection as they follow their path to getting their job.”[119] Claudette Dumont-Smith highlighted the important role played by Friendship Centres in urban centres, and recommended an increase in funding to support their work.[120] The Committee recognizes that many of these suggestions are not within the mandate of Status of Women Canada. Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada continue to encourage the development of the capacity of Aboriginal girls, and consider a specific focus in its funding program on improving their access to existing education and training programs. In addition, the Committee heard that Aboriginal girls and young women often face other challenges related to inadequate or inappropriate housing.[121] The Committee also heard evidence of positive recent developments. In addition to the Minister for Status of Women reporting on the priority being placed on Aboriginal girls and women,[122] other witnesses reported on higher earnings for Aboriginal women with a Bachelor of Arts degree than their non-Aboriginal counterparts.[123] More testimony and suggestions with respect to Aboriginal women’s leadership is addressed in greater detail later in this report. 4. Newcomers to CanadaAccording to Statistics Canada, in 2005, 20% of immigrant girls and women in an economic family lived below Statistics Canada’s low income cut-off before tax, compared with 10% of Canadian-born girls and women.[124] Among the female immigrant population, girls under the age of 15 had the highest incidence of low income, at 40%, which is likely due to “the difficult labour market conditions experienced by their parents.”[125] According to a Girls Action Foundation publication, immigrant girls face unique challenges in the areas of:

The Committee heard testimony focused on girls in immigrant and refugee families in Canada, and the particular cultural, linguistic, and educational challenges they face in seeking to prepare for and participate in Canada’s economy,[127] including not being aware of their rights within Canada.[128] The Committee heard that meeting a family’s basic needs, including affordable housing, is prerequisite to integrating newcomer women into the Canadian economy.[129] More specifically, Bertha Mo, Manager, Counselling Program, Ottawa Community Immigrant Services Organization recommended that government “fund more research on actually how the educational system is working with newcomers”[130] support “ integration support for entire families... [and] vocational and career counselling for girls.”[131] Status of Women Canada officials reported on supports they were providing that targeted immigrant youth,[132] including initiatives involving school boards or other existing providers of services in newcomer communities.[133] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada support community organizations working with girls in newcomer families to assess how they can best be integrated into the social and economic activities of Canada, to share promising practices, and to encourage replication of successful projects. 5. Girls and Women with DisabilitiesAccording to Statistics Canada, in 2006, 46% of women with a disability were employed, compared to 65% of women not reporting a disability.[134] A 2009 article explains the importance of labour force participation for people with disabilities: Persons with disabilities face different barriers to participation in the labour force, even though maintaining an attachment is often crucial for them. Doing so enables them to meet everyday needs and build self esteem, and gives a sense of belonging to the community.[135] The Committee learned that girls and women with disabilities are more likely to be victims of violence, less likely to graduate from secondary school, and face higher rates of unemployment regardless of their qualifications.[136] While the gap in employment rates between disabled and non-disabled people holding graduate degrees has narrowed, cited as good news, it remains at six percentage points.[137] With respect to girls and women with disabilities, the Committee heard of the importance of statistical evidence, seen by witnesses to be less available.[138] Bonnie Brayton, National Executive Director, DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada (DAWN) recommended enhancing income support programs for people with disabilities making them more flexible and transferable, and making post-secondary institutions, including housing, more accessible.[139] More generally, she told the Committee that the federal government should act to ensure that “public policies, programs and funding reflect a commitment to future generations of girls and young women with disabilities in order that they too can look forward to the same opportunities as their non-disabled counterparts.”[140] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada work with Treasury Board to ensure that gender-based analysis take into account the particular needs of girls and young women with disabilities. 6. PovertyAccording to a recent report by Campaign 2000, the rate of child and family poverty in Canada was at 9.5% in 2009 (according to Statistics Canada’s low income cut-off lines after-tax[141]), down from 11.9% in 1989.[142] Therefore, in 2009, around 639,000 Canadian children lived in poverty, which is around 1 in 10.[143] Some children and families are at greater risk of living in poverty; this includes children of single mothers, children of immigrant families, children of Aboriginal families, and families where a child has a disability.[144] Statistics below highlight the situation:

According to a Statistics Canada report, there is a link between a child’s home environment and the child’s academic performance that influences their future economic success.[148] The study notes “the fact that the lower income children were less likely to experience the home environment factor may help to explain the difference in readiness to learn between the income levels.”[149] The Canadian Teachers’ Federation states that many low-income children: …experience reduced motivation to learn, delayed cognitive development, lower achievement, less participation in extra-curricular activities, lower career aspirations, interrupted school attendance, lower university attendance, an increased risk of illiteracy, and higher drop-out rates.[150] Another report documents the poverty-related factors that impact child development in general and school readiness in particular: …the incidence of poverty, the depth of poverty, the duration of poverty, the timing of poverty (e.g., age of child), community characteristics (e.g., concentration of poverty and crime in neighborhood, and school characteristics) and the impact poverty has on the child’s social network (parents, relatives and neighbors).[151] Evidence indicates that poverty also impacts the educational outcomes of Canadian youth, which hurts their economic success. Having a low-income correlates to fewer opportunities to access a post-secondary education:[152] research from 2006 indicated that 58.5% of 18- to 24-year-olds with a family income (before tax) of $25,000 or less were enrolled in a post-secondary institution, compared to 81% of 18- to 24-year-olds with a family income of more than $100,000.[153] As well, strong links have been found between low income, and resulting inadequacy of basic necessities such as housing and nutritious food, and the involvement of child welfare authorities in families.[154] As the Committee heard, poverty of both girls in low-income families and among young women themselves is a significant obstacle to economic participation, as it makes education, housing, transportation, and other goods and services needed to be in the labour market more difficult to obtain. The intersection of poverty with other barriers was highlighted by the Minister for the Status of Women, the Honourable Rona Ambrose, when she described the increased probability of low-income women experiencing violence because of their reduced options.[155] Other intersections were identified, linking poverty to disability,[156] lack of self-esteem,[157] Aboriginal status,[158] involvement in the child welfare system,[159] and immigrant and refugee status.[160] Single mothers in particular are over-represented among low-income Canadians,[161] which has an impact on not only their opportunities, but also the opportunities available to their children, including their daughters. Recommendations focused on the reduction of poverty for these families, and all low-income families,[162] some specifically proposing an increased child benefit.[163] B. Life Skills and Financial LiteracyWitnesses and briefs identified gaps in the skills girls get that have an impact on their economic participation.[164] As described by Leanne Nicolle, “life skills are what keep girls out of the cycle of poverty, and help them reach their full potential.”[165] A general recommendation focused on the need to support life skills programming, and that such programs be adapted and targeted to Aboriginal and other marginalized groups.[166] Several witnesses identified financial literacy as an important building block for economic participation, and moving beyond it to prosperity and leadership.[167] As Ms. Nicolle told the Committee, “Economic security relies on knowing how to manage your money.”[168] Tracy Redies told the Committee: Today we should be educating both women and men to be financially literate at younger ages and to understand the opportunities and pitfalls of finance. They should understand the benefits of saving early, budgeting, and the appropriate use of credit. While financial institutions and other worthy organizations, such as Junior Achievement, have provided some support, given Canadian debt loads and our generally inadequate preparation for retirement, my sense is we're not consistently teaching financial literacy at an early enough age.[169] Ms. Redies emphasized the particular importance of financial literacy skills for girls: “As women still tend to be secondary income earners in general, it is crucial that we teach them how to be financially literate and financially independent from an early age.”[170] Saman Ahsan also recommended “providing gender-specific financial literacy education for girls and women.”[171] Even more specifically, Jocelyne Wasacase-Merasty, Regional Manager, Prairie Region, National Centre for First Nations Governance recommended that economic independence among Aboriginal people could be encouraged by “building the financial literacy among [community people], really promoting that strong administrative practitioner approach, building their capacity, and building those opportunities.” [172] Jocelyne Michelle Coulibaly told the Committee that in all of the federation’s consultations, “Franco-Ontarian youth have reiterated the need for training about financial literacy in French.”[173] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada support initiatives with a particular focus on the development of financial literacy, including projects that target Aboriginal girls and girls in other marginalized groups including minority language groups. C. Transition from School to WorkWomen under 25 fare better in employment than young men with the same levels of education. For example, in 2009, 77.2% of women aged 15 to 24 with a non-university post-secondary certificate or diploma were employed, compared to 73.0% of young men.[174] Despite these advances by young women in the labour market, some challenges persist:

Witnesses identified the challenge facing many girls as they make the transition from school (at whatever level) to the labour market. Again, these challenges often coincided with other disadvantages, such as involvement with the child welfare system,[178] Aboriginal status,[179] poverty, and immigrant status.[180] After describing her own situation post-graduation, Farrah Todosichuk, Representative, YWCA Canada, told the Committee: “Young women need help to build their skills, to broaden their resumés and to get the experience they need in order to make the transition from school to employment more successful.”[181] Barbara Byers identified the need for transitional supports, especially for women entering careers in trades and technology, suggesting that government could be of assistance by ... supporting youth apprenticeship and school-to-work transition programs; funding employability training programs and bridging programs, which encourage women to retrain for work in trades and technology; and by supporting women's needs while they're in training or apprenticeship.[182] Similarly, Laurel Rothman, National Coordinator, Campaign 2000 called on government to “support some kind of career entry... or first job opportunity;”[183] while the YWCA recommended that government “increase support for youth to bridge to a first career position.”[184] Two witnesses specifically recommended internships to ease this transition. Tracy Redies told the Committee: “We can do more to help support young women through earlier, creative internships and business experiences that help build self-confidence and skills.”[185] Paige Isaac highlighted the value of internships for Aboriginal youth making the transition: “Creating interesting internships and really trying to integrate [A]boriginal people into the marketplace would be interesting. I've heard from a few students that internships really helped to empower them.”[186] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada work with private-sector partners to encourage the development of mentorships and other mechanisms by which girls can achieve economic prosperity. PROSPERITYThe Committee’s motion identified economic prosperity as one of the goals for girls and young women. A number of witnesses identified the areas where girls’ economic prosperity could be advanced and enhanced. A. Non-Traditional EmploymentIn December 2010, the Committee on the Status of Women completed a study on non-traditional work, and released a report entitled Building the Pipeline: Increasing the Participation of Women in Non-Traditional Occupations,[187] which indicated that there was significant under-representation of women in non-traditional jobs, including construction trades, engineers, and mining and exploration.[188] According to witness testimony cited in the 2010 report, the employment choices that women make are strongly influenced by factors that start at an early age, such as culture, family and school.[189] Some girls are socialized from an early age “to believe that some jobs are out of reach for them.”[190] Witnesses highlighted many of the same influencing factors during this most recent study. Canadian girls are significantly less likely than their male counterparts to take vocational training and programs, and to eventually participate in the economic realm of non-traditional employment. According to one study, Canada placed second from the bottom in graduation rates for girls for vocational and pre-vocational programs, out of 32 member countries of the OECD.[191] The Committee heard that girls’ future economic prosperity could be improved by encouraging them to pursue careers in the realm of non-traditional employment, where the rate of employment is high and there are favourable salary and compensation situations.[192] Witnesses indicated that non-traditional employment included careers in trades, science, technology, engineering and mathematics.[193] Women in management and senior executive positions will be discussed in the upcoming section on leadership. Several witnesses spoke of existing or anticipated labour shortages and the possibility of training women in order to fill those positions.[194] A witness, who is a CEO for a company in the field of global vehicle and mobile industrial equipment markets, stated that her company wants to increase its overall percentage of female employees, but is frustrated that there are not enough women receiving an education in this area for the company to hire.[195] Similarly, the Committee heard during their 2010 study that many vocational sectors are experiencing skilled labour shortages, which offers important employment opportunities to women.[196] Therefore, improved participation in the non-traditional employment sector is an important contributor to girls’ economic participation. A number of reasons were given as to why girls and young women tend not to pursue non-traditional careers; some of these include the stereotypes of such jobs, which colour girls’ perception,[197] a male-dominated culture in the majority of these workplaces that may overlook the exclusion and harassment of women,[198] and the demanding workplace schedules, which make the jobs less family-friendly and flexible.[199] Witnesses in this study also cited the declining levels of confidence of girls in elementary school, particularly in the fields of study related to non-traditional employment;[200] confidence levels will be elaborated upon in a following section. It was noted that girls have diverse talents and skills, some of which could contribute to greater success in non-traditional fields, and that these girls should be guided in that direction.[201] Some witnesses indicated that there should be a shift in the gender dynamics of the labour force; with a greater respect of and economic compensation for work traditionally dominated by women,[202] and a move towards greater female participation in non-traditional jobs, so that they “become jobs for all.”[203] Witnesses spoke of the benefits of diversifying the workforce in the non-traditional sector, indicating that productivity, problem-solving, and competitiveness are all improved by diverse teams that include women.[204] It was also noted, by witnesses, that unions have actively encouraged the participation of women in non-traditional realms, such as skilled trades or construction.[205] The Committee heard general recommendations to develop strategies and provide programs for girls with the aim of narrowing the gender gap in non-traditional employment.[206] Witnesses also provided specific recommendations, for the development of awareness campaigns directed at girls,[207] an investment in science, technology, engineering, and math outreach programming with the goal of developing science literacy among young girls,[208] and the building of a national strategy targeting science education from K-12.[209] Jennifer Flanagan, President and CEO of Actua, spoke of the need for investment in programming for girls in the non-traditional fields: These types of programs are playing a significant role in building resiliency and economic independence among girls and young women. This will also result in a significant overall contribution to economic prosperity and a much needed boost to diversity and the job force.[210] The idea of a national strategy was expanded upon by Elyse Allan: As a country we can do more to encourage children, and especially girls, to study science and maths in the crucial K through 12 years. The provinces will have a lead role here. But the federal support for post-secondary education can also help out.[211] In order to increase women’s presence in the non-traditional realm, witnesses recommended paying special attention to the enrolment and graduation of young women in relevant programs,[212] and specifically employing a collaborative approach with universities and colleges[213], as well as industry partners.[214] Linda Hasenfratz recommended collaboration with and among universities and colleges, with the goal of: ...being the best in the world in terms of the calibre and the number and the success rate of engineers and scientists that we are creating, with a very specific goal of increasing the percentage of women in those areas.[215] Witnesses also recommended that there be federal involvement in supporting and funding youth apprenticeships, school-to-work transition programs and other employability training programs.[216] Recommendation: To support and encourage the increased participation of girls in non-traditional employment, the Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada:

Officials from Status of Women Canada informed the Committee that the Women’s Program had issued a call for proposals, in February 2011, that included three themes related to economic prosperity through non-traditional employment: “One [theme] was to increase the recruitment of women in non-traditional employment. One was to increase their retention in non-traditional employment, because [it was] found at times that people were successful in attracting women but not successful in retaining the women … The third … had to do with creating growth and financial opportunities for women business owners.”[217] B. Role Models for Non-Traditional EmploymentWitnesses indicated that historically, a lack of female role models in trades, technology, business and other non-traditional careers meant that girls could not imagine themselves pursuing their studies and a career in these fields, even if they were interested.[218] With more recent increases in the number of women in these professions, girls have become more likely to imagine themselves in these professions and to look to these women as role models.[219] Some female witnesses pointed to the important influence of role models in their own lives.[220] The Committee heard that a majority of the programs aimed at getting girls interested in non-traditional employment use the role-model approach, and that witnesses find it effective.[221] It was explained that when female role models met with girls directly, they could answer questions about their work and inspire girls to continue their studies.[222] Witnesses recommended that role modelling be widely promoted, particularly in the area of non-traditional employment, with the aim of inspiring young girls.[223] One witness suggested financial support be given to mentorship programs designed to introduce “young girls to inspirational women scientists and engineers who can share their stories and dispel the still existing stereotypes.”[224] Recommendations with respect to role models are contained in a later section focused on role-modelling and leadership. Another witness recommended that the federal government provide opportunities and support for their own employees, such as government engineers, to attend school events and participate in programs.[225] C. EntrepreneurshipGirls’ economic prosperity can be promoted by encouraging entrepreneurship, and the economic independence that comes with running your own business.[226] It was noted that more women are starting their own small or medium-sized businesses.[227] Witnesses recommended approaches to assisting women in the realm of sustainable business: that support be provided for developing social enterprises,[228] and that the federal government develop micro-financing and business development solutions for women and their communities.[229] As well, one witness recommended the implementation of “enterprise development, supply chain, and marketing practices that empower women.”[230] D. Pay Gap and CompensationAccording to Statistics Canada, women’s average total income is lower than men’s, although the wage gap varies depending on a several of factors, such as province of residence[231] and educational attainment.[232] In every age group, women’s average total income was lower than men’s, but the gap was smallest for young women between 16 and 19, who had incomes of about 90% of the income of young men. For women aged 20 to 24, their incomes were about 75% of the incomes of young men.[233] Table 1 – Average annual earnings of women and men employment full-year,

Source: Cara Williams, “Economic Well-being,” in Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report, Sixth edition, Statistics Canada and Status of Women Canada, December 2010, p. 15, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11388-eng.pdf. Statistics Canada reports that “women’s employment earnings are on average still lower than men’s, even when they have the same education level.”[234] Among witnesses, there was widespread agreement of the ongoing challenge of a gender wage gap in Canada, and the necessity in narrowing and eventually eliminating this gap.[235] The wage gap for Aboriginal women, disabled women and racialized women was noted as even more significant.[236] The Committee also heard that traditional career choices often result in women choosing care-giving and human services roles in employment, which are often associated with lower incomes. Associated recommendations focused on valuing work women traditionally do, possibly through collaboration with the public and private sectors, and on establishing, monitoring and improving federal employment and pay equity policies. A number of witnesses also stated that young women are more likely to hold jobs that are part-time, precarious or temporary in nature.[237] The nature of employment in turn affected their compensation, as these jobs tend to be lower-paying, with few benefits, no workplace pension, and the additional unlikelihood of qualifying the women for employment insurance.[238] The Committee heard from one witness that this type of employment severely limits a young woman’s economic prosperity, and in fact, can trap her in a low-income situation.[239] A witness recommended that the government address the issue of under-employment and precarious work, as young women are among the most likely to work in these conditions.[240] Witnesses expanded on the idea of closing the wage gap by recommending the implementation of the recommendations made by the federal government Pay Equity Task Force[241] or the development of legislation with the aim of identifying, quantifying and eliminating the wage inequity.[242] One witness spoke of the benefits of unionization for women, indicating the accompanying retirement plans and social benefits.[243] Statistics Canada data show that the unionization rate among employed Canadians has risen for women, from 22.3% in 1978 to 32.6% in 2009, while the rate for men has decreased in the same time period.[244] The Canadian Labour Congress reports that unionized women earn more than $5 an hour more than non-unionized women, and that “ … on average, full-time unionized women earned 95% as much per hour as their male counterparts, and part-time women in unions actually earn more.”[245] E. Negotiating SalaryWitnesses told the Committee that the future economic success of girls can be directly tied to their starting salaries and their ability to negotiate that salary.[246] Cara Coté, Vice-President of the Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs, said that a lower initial salary follows young women throughout their careers, and contributes to the pay gap as their salary will remain comparably lower than young men who were able to negotiate a higher starting salary.[247] She explained: …I find that [young women] are having issues negotiating a proper salary. It comes down to confidence… in the last… 10 years that I've been involved with hiring and managing employees I have noticed that there is almost no negotiation for wages when they first start. And that will follow them throughout their careers. They start at a lower wage, and each time they get an increase, it's still lower than what a male counterpart would have. That follows them until they retire, pretty much.[248] The challenge in negotiating salary is linked to lower levels of confidence among young women[249] and the high unemployment and under-employment that young women face; as one witness explained “it is difficult for any young person to think about negotiating a salary when that person feels lucky just to get a job in the first place.”[250] One witness recommended that salary negotiation skills be included in the curriculum for students, particularly at the secondary school level.[251] Recommendation: The Committee recommends that Status of Women Canada encourage the development of a curriculum to teach girls salary negotiation skills. LEADERSHIPEconomic leadership was identified by the Committee’s motion as one of the goals for girls and young women. A number of witnesses discussed the areas where women’s leadership opportunities fell short, and the strategies to employ in order to increase girls’ chances at future economic leadership. A. Women in Decision-Making PositionsGender imbalance persists in many decision-making positions, particularly within the political and business spheres in Canada. For example:

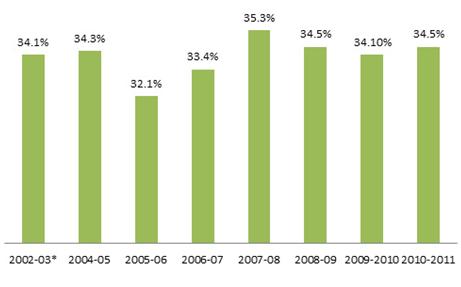

The Committee heard that girls need to see powerful women as role models, holding “in government, in prominent decision-making roles [and] at the head of leadership.”[255] One witness recommended that government provide space and funding for women to “develop their leadership potential and build specific skills necessary in [their] communities, [their] careers, and [their] personal lives.”[256] The Committee heard from Status of Women Canada officials that one of the Women’s Program’s priorities is encouraging women and girls in leadership and decision-making roles.[257] In its promotion for the upcoming International Day of the Girl, Status of Women Canada recognized that the day’s value lies in its ability to “empower girls as citizens, leaders and powerful motivators of change.”[258] 1. Women in Senior Management and Executive PositionsWitnesses told the Committee that women remain under-represented in senior management positions[259] and in executive positions for corporations,[260] despite the fact that more women have been pursuing studies in the areas of business and management.[261] While Canadian women make up 47% of the labour force in 2011,[262] they face challenges in the business sector when it comes to equal advancement and representation in decision-making positions. In Canada, women earned 34.5% of the Masters in Business Administration (MBAs), a percentage that has been roughly the same over the past decade (see Figure 2).[263] Figure 2 – Women’s Shares of MBAs Earned in Canada