FAAE Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

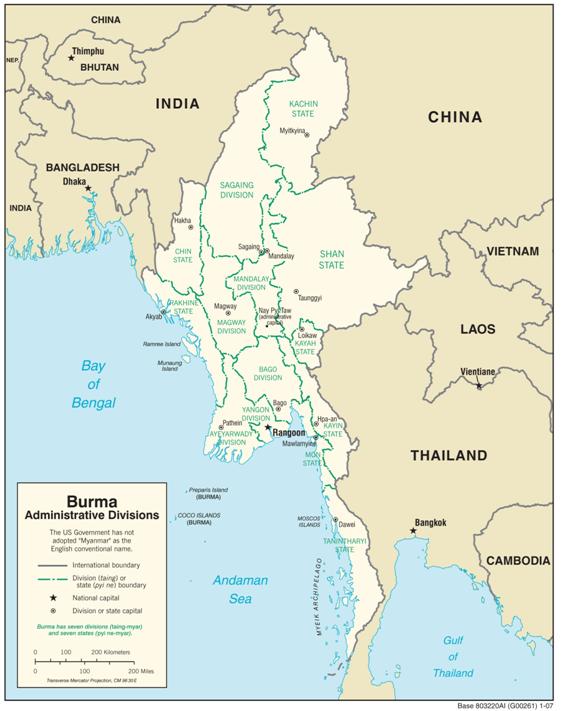

BURMA: A BRIEF OVERVIEWDuring the Subcommittee’s hearings, witnesses described how Burma’s history, geography and ethnic makeup have had an impact on its governance and on respect for human rights in the country. Witnesses also stressed that the current reform process must be understood in light of Burma’s authoritarian past and its ethnic and religious diversity. Mr. Giokas from DFAIT provided a short overview of some of these factors. He explained: Burma is a country of some 60 million people, located at the crossroads of Asia, bordering India, China, and Thailand. The Burman majority[10] is predominantly Buddhist, but the government recognizes 135 national races, which generally fall under seven major ethnic groups. These ethnic groups predominate in Burma's rugged border areas and collectively constitute roughly 40% of the country's population, while occupying as much as 60% of its territory. Burma is approximately the size of Alberta, but its territory includes almost 2,000 kilometres of coastline and numerous islands in the Andaman Sea. A British colony until the late 1940s, it is blessed with a wide range of natural resources, including timber, precious gems and minerals, and energy in the form of natural gas deposits and hydroelectricity potential. Despite these riches, decades of conflict, mainly in the ethnic-dominated border regions, and oppressive military rule have left the Burmese people among the poorest in the region. According to the latest UNDP [United Nations Development Programme] data, Burma ranks 149 out of 187 countries on the Human Development Index. It is the least developed country in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The average life expectancy is just over 65 years.[11] Figure 2: Map of Burma Showing Political Divisions

Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Maps: Burma. From 1962 until 2010, Burma was ruled by a military dictatorship. Over the last 25 years, its history has been particularly turbulent. Widespread pro-democracy protests that took place in 1988 were met by a violent military crackdown. On 8 August 1988, the military fired on unarmed demonstrators, killing more than 1,000 protestors. In September 1988, the military suppressed ongoing protests, killing thousands more and leading many to flee or leave the country. A new ruling junta called the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) was established, deposing the previous military government led by General Ne Win and suspending the constitution. The SLORC ruled by martial law until elections were held in May 1990. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD party won an overwhelming victory; however, the ruling junta refused to honour the results and embarked on a campaign of repression, imprisoning many political activists, including Daw Suu Kyi.[12] In 2007, large public protests occurred in response to the government’s decision to increase fuel prices without warning. The protests expanded in September 2007, with Buddhist monks taking a leading role. The protest movement became known as the “saffron revolution” after the colour of the monk’s robes. The military government launched a brutal crackdown, attacking peaceful demonstrators and firing live rounds in crowds. Nighttime raids rounded up thousands of monks and civilians, many of whom were later imprisoned. Internet activity was shut down throughout the country.[13] In May 2008, a massive cyclone, Nargis, struck the Burmese coast, leaving an estimated 140,000 people dead and many more displaced or otherwise affected. The Burmese military government, unwilling or unable to provide adequate relief itself, nevertheless initially refused to permit access by international humanitarian agencies and delayed the distribution of international relief supplies.[14] Also in 2008, the military government drafted a new constitution that provided for the creation of an elected civilian government, but also entrenched overall military control. The constitution was eventually “approved” in a 2008 referendum that was considered neither free nor fair by the international community. In response to the massive human rights violations committed by the Burmese junta over the last two decades, Canada and several other Western countries imposed a range measures, including diplomatic and economic sanctions. For example, Canada suspended development assistance following the 1988 crackdown on student protestors, excluded Burma from the least-developed country market access initiative, and, after 1997, banned virtually all exports to Burma.[15] In 2007, following the repression of the saffron revolution, Canada imposed a comprehensive ban on imports, exports and investment.[16] These sanctions cut off virtually all trade between Burma and Canada.[17] A. Applicable Human Rights FrameworkThe Subcommittee begins by observing that the Charter of the United Nations requires all states to develop and encourage respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.[18] Given its authoritarian past, however, it is perhaps not surprising that Burma has ratified relatively few universal human rights conventions. The Subcommittee has, therefore, considered Burma’s human rights record in relation to the international legal obligations contained in human rights treaties that both Burma and Canada have ratified. In addition, the Subcommittee has looked to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as an important source of human rights standards applicable to Burma. The treaties discussed below and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provide the benchmarks against which each country’s overall human rights record is assessed as part of its Universal Periodic Review by the UN Human Rights Council, a process that aims to periodically review the human rights record of every state that is a member of the United Nations. Burma has binding international human rights obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (CRC-OP-SC), as well as the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. In relation to human trafficking and human smuggling, Burma is also bound by obligations under the Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children[19] and the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. Finally, Burma has ratified two of the fundamental conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), a UN specialized agency with a mandate to draw up and oversee international labour standards, namely the Forced Labour Convention (No. 29) of 1930 and the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention (No. 87) of 1948. As a result, Burma must act in accordance with the obligations contained in these treaties. Notably, Burma has not ratified either of the two most important universal human rights treaties, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (IESCR), nor has it ratified the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness.[20] The Subcommittee hopes that as Burma embarks on this new era of reform, its government and parliament will give serious consideration to ratifying these and other core international human rights treaties, the Convention and Protocol relating to the status of refugees, the Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, as well as bringing its domestic legislation into compliance with the obligations contained therein. [10] The word “Burman” refers to members of the majority ethnic group in Burma. The term “Burman” should not be confused with the term “Burmese” which refers to persons from the country of Burma, regardless of ethnicity. [13] Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, mandated by resolution S-5/1 adopted by the Human Rights Council at its fifth Special Session, 7 December 2007, UN Doc. A/HRC/6/14. [14] See, e.g.: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs [OCHA], Myanmar: Cyclone Nargis OCHA Situation Reports Nos. 1, 4, 7, 34 of 4, 7 and 10 May 2008 and 23 June 2008, respectively. The Government’s response is discussed in International Crisis Group, Burma/Myanmar After Nargis: Time to Normalise Aid Relations, 20 October 2008. [15] Export controls were put in place when Burma was added to the Area Control List, SOR/81-543 under the Export and Import Permits Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. E-19. Burma was removed from the Area Control List by Order of the Governor in Council on 24 April 2012. [16] These measures were taken under the Special Economic Measures Act, S.C. 1992, c. 17. [18] Charter of the United Nations, art. 1.3. [19] Also known as the “Palermo Protocol,” or the “Trafficking Protocol,” this treaty is a protocol to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime, to which Burma is also a party. [20] As part of the Universal Periodic Review Process, the Convention on the Status of Stateless Persons is considered for those states that have ratified it. Neither Canada nor Burma has ratified this treaty. |