FAAE Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

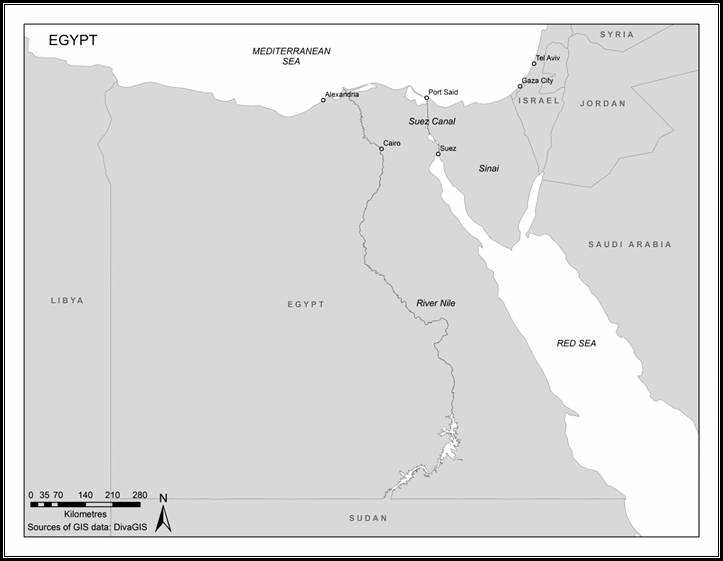

SECURING THE HUMAN RIGHTS OF COPTIC CHRISTIANS IN EGYPT AFTER THE ARAB SPRING: A VIEW FROM CANADA'S PARLIAMENTIntroductionIn December 2010, a Tunisian street vendor set himself on fire in protest over his poor treatment by government officials. His act set off a wave of protests in Tunisia, toppling the Tunisian government within weeks and spreading quickly across the Arab world. This series of popular protests, which toppled dictators and forced authoritarian regimes to grant greater democratic freedoms to their people, has become known as the Arab Spring. Massive protests against Egypt’s former dictator, President Hosni Mubarak, began in late January 2011 and gained momentum until they forced his resignation on February 11, 2011. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), led by Field Marshal Tantawi, took power in Egypt after former president Mubarak was deposed. Over the past 18 months, the Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade (the Subcommittee) has studied the situation facing Coptic Christians in Egypt in the wake of the Egyptian revolution.[1] The Subcommittee heard from witnesses and received written submissions as part of its study. Based on the evidence received and on publicly available information, the Subcommittee agrees to report the following findings and recommendations to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development. The first of the Subcommittee’s hearings were held in November and December of 2011. At the time the study began, after nine months of military rule, it was still unclear how the transitional SCAF government was, in fact, going to transition the country from military to civilian rule. Egyptians were becoming increasingly impatient as the reforms they had hoped to see — political, social and economic — remained elusive. Further, a disturbing trend was beginning to emerge: the military, which had appeared to protect and even join with protestors during the uprising against former president Mubarak, began to violently repress ongoing demonstrations in which Egyptians continued to demand access to jobs, justice and a full transition to democracy. As the situation in Egypt continued to evolve, the Subcommittee held additional hearings on the human rights situation in Egypt after the country’s first parliamentary elections, which took place between November 2011 and January 2012; following the election of President Mohamed Morsi on June 24, 2012; and again in the wake of the adoption of Egypt’s new constitution in December 2012. Figure 1 — Map of Egypt (North Africa)

The Challenge: Supporting Democratic Change while Protecting the Human Rights of all Egyptians, Including the Coptic MinorityThe Subcommittee believes that the popular uprising against the regime of former president Mubarak and the peaceful, democratic election of President Morsi have created an opportunity for Egypt and its people to build a tolerant, pluralistic democracy. The Subcommittee was told that Muslims and Christians have coexisted in Egypt for centuries and that Egyptians of different faiths marched together at Tahrir Square to overthrow former president Mubarak, under banners proclaiming: “We are all Egyptians.”[2] The Subcommittee notes, furthermore, that President Morsi has pledged on several occasions to protect minority communities in the country. At the same time, the Subcommittee heard from witnesses that the fall of the old regime in Egypt has presented particular challenges for the Coptic community, which has experienced an increase in attacks and discrimination since the beginning of the Arab Spring. In the course of the Subcommittee’s study, it became clear that respect for the human rights of Coptic Egyptians and other minorities is tied directly to respect for the rule of law in the country more generally. The challenge for the Subcommittee is to recognize and support the positive steps that the Egyptian people are taking on the road toward establishing a democracy, while sounding the alarm about human rights violations and abuses, as well as the emergence of a political discourse that is intolerant of dissent and difference. The Subcommittee is concerned that these developments threaten to derail Egypt’s promising democratic progress. Overview of Political Turmoil in Egypt Since the RevolutionSince the fall of former president Mubarak’s regime, and despite significant challenges, a civilian government has slowly been taking shape in Egypt. Nevertheless, the transition process has been marked by serious security concerns, as well as by power struggles between the presidency and other branches and institutions of government. In this context, political conflict and violence between Islamist political forces and other political and social groups in the country, coupled with a failure on the part of state to uphold the rule of law, now threaten to undermine the revolution’s achievements.

Democratic legislative elections were held in Egypt in the spring of 2012. However, that June, just prior to the final round of voting in the presidential election, Egypt's highest court ordered the dissolution of the lower house of the Egyptian Parliament (the People’s Assembly). This order was carried out by the SCAF. The upper house of Parliament, the Shura Council, was not implicated by the court’s ruling and has continued to sit, although it does not have a significant legislative role. With the People’s Assembly dissolved, the SCAF implemented a series of constitutional decrees on June 17, 2012, giving itself executive and legislative powers, and limiting the authority of Egypt’s future president. The democratic election of President Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Freedom and Justice Party, was announced on June 24, 2012 and Egypt’s new leader was sworn into office on June 30, 2012. The following month, in August 2012, President Morsi announced that he would take over the SCAF’s executive and legislative powers until a new constitution came into force and a new legislature was elected. He also announced the retirement of Field Marshal Tantawi, the leader of the SCAF, following a failure by the Egyptian military to prevent a terrorist attack in the Northern Sinai Peninsula that killed 16 Egyptian soldiers.[3] This move ended the transitional period of formal military rule that had lasted since the ouster of Hosni Mubarak. The 2012 Constitution-drafting ProcessA Constituent Assembly made up of 100 people was tasked with drafting a new constitution for Egypt. The Assembly was appointed by the Egyptian parliament, prior to the dissolution of its lower house, under a March 2011 constitutional decree made by the SCAF. The Assembly included “40 members of [the dissolved] parliament, 21 public figures, 10 legal and constitutional scholars, six union representatives, five members of the Al-Azhar institution, one member of the military and one representative of the police.”[4] The Assembly originally included eight Copts and eight women, but many of these individuals withdrew from the Assembly before the draft constitution was completed.[5] Reflecting the make-up of the parliament that appointed its members, the Assembly was dominated by Islamists, including the Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt’s ultra-conservative Salafist parties.[6] Due to the dominance of Islamist political forces in the Constituent Assembly, the drafting process was plagued by controversy from the outset.[7] Secular and “liberal” political forces in Egypt considered the Constituent Assembly to be insufficiently representative of Egyptian society. Court challenges seeking to have the Assembly dissolved were launched by some political factions. Between late October and mid-November 2012, the constitution-drafting controversy reached a crisis point. During the third week of November 2012, representatives of the Coptic Church and many representatives of liberal and secular groups, including journalists, human rights activists and opposition political parties, withdrew from the Assembly and indicated their belief that it should be dissolved by the courts.[8] In November 2012, President Morsi issued a constitutional decree assuming sweeping powers and immunizing his decisions from legal challenge,[9] which led to large protests by pro- and anti-Morsi factions in Egypt that were marred by frequent violence.[10] While this decree was in force, the new constitution was finalized by the Constituent Assembly, from which Coptic Christian representatives and many other groups had withdrawn. After the drafting process was completed, President Morsi rescinded his decree.[11] The constitution was approved by Egyptians in a “lightning referendum” held in December 2012.[12] Turnout in the referendum was approximately 33%, with 63% of voters supporting the new constitution.[13] In the Subcommittee’s opinion, the constitution-drafting process illustrates critical weaknesses in Egypt’s transition to democracy that have had significant implications for the protection of human rights in the country in general, and for the Coptic community in particular. The Subcommittee was told that the Islamist majority in the Constituent Assembly came to the conclusion that it could not reach an agreement with non-Islamists, including Coptic Christian representatives and members of liberal and secular opposition groups. At this point, rather than compromising on key issues, they chose to push through a constitutional document.[14] As a result, the Subcommittee was told that the constitution-drafting process failed to produce a constitution that different groups within Egyptian society accept as legitimate, which in turn has led to an unstable political environment in which the basic rules are not accepted by different actors.[15] Overall, witnesses said that Egypt’s Coptic community is deeply and legitimately concerned about the inability of the political process to deliver a functioning government that respects and protects all Egyptian citizens equally.[16] Moreover, the Subcommittee was informed that in key areas, the Constitution failed to meet international standards.[17] On a more positive note, however, the Subcommittee was pleased to learn that the upper house of Parliament, the Shura Council, recently accepted a judicial assessment that a proposed election law was unconstitutional and amended the bill in question. When the Shura Council failed to submit the revised bill for constitutional review before passing it into law, a court suspended operation of the legislation.[18] The Subcommittee believes that this show of vitality from the courts is a positive development. It is hoped that over time, Egypt’s judicial institutions will be able to give meaning to the human rights guarantees enshrined in Egypt’s constitution. The Muslim Brotherhood and the Freedom and Justice PartyThe Freedom and Justice Party is the political party of the Muslim Brotherhood movement. The Muslim Brotherhood is often called an “Islamist” movement in the Western media. It was founded with the goal of establishing an Islamic state and instituting Shari’a law in Egypt. The movement has a history of violent political action, primarily between the 1940s and the 1960s. More recently, however, prominent members of the Brotherhood have publicly denounced the use of violence as a means to achieve political goals.[19] The Subcommittee was told that the Muslim Brotherhood movement has a pragmatic and ideologically flexible side; for example, officials from the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) informed the Subcommittee that the Brotherhood made “serious attempts to reach out to the Coptic Christian community” following the 2012 elections.[20] On the other hand, a more hardline faction exists within the movement.[21] Mark Bailey, Director General, Middle East and Maghreb Bureau, DFAIT, and Professor Nathan Brown both indicated that in their view, the Muslim Brotherhood appears to be relatively positive towards political freedoms.[22] On issues like cultural rights and full respect for the human rights of women, the Brotherhood’s record, however, raises serious concerns for the Subcommittee. Professor Brown said that in his assessment, both the government of President Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood have a fairly robust view of democracy, but one that is majoritarian in nature. He told the Subcommittee that, because the majority of Egyptians have favoured Islamist parties in elections since 2011, the Muslim Brotherhood is of the view that this majority “should have a fairly free hand” in governance and law-making. Professor Brown characterized this perspective as “a view of democracy that you could say is democratic but not completely liberal.”[23] Respect for the Human Rights of Coptic Christians in a Time of TransitionIn Egypt, Sunni Islam is the official state religion and is followed by just under 90% of Egyptians.[24] The Coptic Christian community is estimated to make up between 8% and 12% of the country’s population of 85 million people. Less than 2% of the population belongs to other Christian denominations and less than 1% of Egyptians are Shi’ite Muslims. There are between 1,500 and 2,000 Baha’i’s and 100 Jews in Egypt. Other faith communities include Qur’anists and Ahmadiya Muslims, whose numbers are said to be “small.”[25] Article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and article 14 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, both of which have been ratified by Egypt, affirm that the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion is the inalienable right of all individuals.[26] As One Free World International pointed out in its written submission, provided to the Subcommittee by Reverend Majed El Shafie, a concern for religious freedom does not require an identification with (or even an affinity for) a particular religion or even religion more generally. On the contrary, a concern for freedom of religion is intrinsic to the basic belief, shared by all who care about human rights, that no one should be killed or denied rights solely based on their beliefs — whatever those may be.”[27] The Subcommittee believes that the right to freedom of religion or belief is inseparable from democratic freedoms and closely linked to the creation of tolerant, secure and peaceful societies.[28] It underpins and impacts on the enjoyment of all the other internationally protected human rights in any healthy democracy, including the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, the right to live free from discrimination, and the right to equality before the law. Thus, any failure to respect the right to freedom of religion or belief will invariably undermine these other rights. At the same time, a state that fails to uphold the rule of law, to ensure that all of its citizens receive equal benefit of the law, and to protect all of its citizens from discrimination cannot hope to promote, respect and protect the religious freedom of its people.

The Subcommittee is of the view, therefore, that the manner in which President Morsi’s government treats Egypt’s Christian minority is, and will continue to be, an important barometer for measuring overall respect for human rights in the country. As the following section will show, the situation of the Coptic minority in Egypt is affected not only by state policies, decisions and actions directed specifically at Copts because they are Copts, but also by a broader failure to protect, as well as ensure equality before the law and the inclusion in the political process of minority and opposition groups generally. The testimony presented to the Subcommittee clearly indicates that the current government is only the latest in a succession of regimes that have not promoted, respected or protected the human rights of religious minorities, including the country’s Coptic Christian minority, to the full extent guaranteed by Egypt’s current and past constitutions and by international law. The Subcommittee urges Egypt’s new government, therefore, to take immediate steps to live up to its obligation to guarantee the human rights of all Egyptians, regardless of religion or belief. Discrimination and Freedom of Religion in EgyptEquality for all citizens before the law, without discrimination, is guaranteed in Egypt’s new constitution and was also guaranteed under the previous constitution of 1971. All Egyptian citizens are also assured equal opportunities, without discrimination.[29] However, despite these constitutional guarantees, Egypt’s Copts have long faced discrimination vis-à-vis their Muslim counterparts, both legally and in practice. Islamic law, or Shari’a, has been the primary source of law under the Egyptian constitution since former Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat amended the constitution in 1980.[30] Don Hutchinson, Vice-President and General Legal Counsel of the Religious Liberty Commission of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, testified that Egyptian Government pronouncements and certain court rulings made prior to the 2011 revolution made Egypt’s acceptance of international human rights obligations subject to these obligations being consistent with Islamic law.[31] According to witnesses, the courts have, at times, interpreted such principles to uphold national laws that violate human rights, or the discriminatory application of the law by Egyptian authorities.[32] As a result, legislation and administrative practices restricting freedom of religion and discriminatory practices continue to exist in Egypt.[33] The Right to Freedom of ReligionEgypt’s New ConstitutionThe Subcommittee notes that Egypt’s new constitution assures Coptic Christians, as well as Sunni Muslims and Jews, the right to freedom of religion or belief, as well as the right to regulate their own religious affairs and to select their own spiritual leaders. Members of these three Abrahamic religions are also guaranteed the right to use their own religious principles to govern personal status matters, which includes family law and inheritance. Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab, International Advocacy Officer at the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, told the Subcommittee that article 3 of the new Egyptian constitution “actually affords those practicing Abrahamic faiths, including Coptics, [other] Christians, and Jews, more rights than under the Mubarak constitution.”[34] Important protections for other human rights are also enshrined in the new constitution, including protections against arbitrary detention, against torture, guarantees of freedom of movement, privacy, and freedom of association.[35] On the other hand, the Subcommittee is worried that certain provisions in the constitution have the potential to restrict the right to freedom of religion or belief, and to entrench and legitimize religious discrimination. For example, Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab expressed particular concern regarding the level of protection for the human rights of faith communities other than the three explicitly recognized in the constitution (Muslims, Christians and Jews), as well as the rights of non-believers.[36] She cited article 43 of the constitution, which states: “Freedom of belief is an inviolable right,” but goes on to provide that the state is only required to “guarantee the freedom to practice religious rites and to establish places of worship for the divine religions, as regulated by law.” In addition, Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab drew the Subcommittee’s attention to article 10 of Egypt’s new constitution, which provides that The family is the basis of the society and is founded on religion, morality and patriotism. The State is keen to preserve the genuine character of the Egyptian family, its cohesion and stability, and to protect its moral values, all as regulated by law.[37] Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab suggested that this provision “could give the state authority, in an attempt to protect the morality of society, to interfere in private family affairs.”[38] In particular, she pointed out that unrecognized religious minorities such as the Baha’is and the Shi’ites could be affected. The new constitution also requires that the Al-Azhar Institution, which encompasses the bulk of the Egyptian Sunni religious establishment, be consulted on matters relating to Shari’a law. Professor Brown told the Subcommittee that the Al-Azhar Institution is currently led by a Sheik who is receptive to “the idea of reaching out to other religious communities.”[39] Freedom of Worship and Conversion

Witnesses explained that Christians in Egypt need special permission from the government to build or repair their churches and do not receive funding from the state for their cultural and educational institutions. There are no similar requirements, however, for the repair and construction of mosques. Additionally, Islamic institutions and universities receive state funding.[40] The Subcommittee also heard disturbing testimony of recent incidents where Coptic churches had been attacked and even demolished, following which the community was denied permission to make repairs or rebuild.[41] The Subcommittee emphasizes that the right to freedom of religion includes the right to manifest one’s beliefs by building places of worship and the freedom to establish seminaries and religious schools.[42] Witnesses also told the Subcommittee that Muslim converts to Christianity face particular discrimination, criminalization, and even torture in detention — especially if they attempt to proselytize.[43] The Subcommittee was informed that, while there is no explicit prohibition on conversion or proselytizing under Egyptian law, some articles of the Egyptian penal code that criminalize the disparaging or degrading of religion as threats to public order have been interpreted to prohibit the proselytization and conversion of Muslims. Egyptians are required to have their religion identified on their national identification cards. The Subcommittee has been informed of instances where government officials have denied Muslim converts to Christianity the ability to change their religious affiliation on their cards. Christian heirs of converts have also had difficulty inheriting property and there are reports that individuals with Islamic names have been prevented from entering Christian churches by police. Moreover, the pervasiveness of discrimination against Muslim converts to Christianity exposes such individuals to threats and violence from private individuals, up to and including death threats from extremist groups.[44]

The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief recently examined the question of conversion through the lens of international human rights law. The Special Rapporteur has stressed that the right to freedom of religion or belief in international law includes the right to convert, as well as the right to try to convert others in a non-coercive way.[45] Forcible conversions or re-conversions are prohibited by international law and standards. The Subcommittee observes that Egyptian authorities therefore have an obligation to repeal any criminal offences punishing conversion and remove any administrative barriers to conversion. Egypt must act to protect converts from violence and should promote tolerance and non-discrimination in its society.[46] The Right to Live Free from DiscriminationOverall, despite constitutional guarantees of equality, Christians and other non-Muslims are not treated equally vis-à-vis their Muslim counterparts in Egypt.[47] The Subcommittee was told that Islamic religious principles have been interpreted by some in Egypt to mean that a non-Muslim cannot exercise control over a Muslim, or in other ways that undermine the equal enjoyment of human rights for all. For example, a witness said that judges sometimes do not accept testimony from a non-Muslim against a Muslim, violating the right to equality before the law.[48] Informal discrimination (as opposed to legally-sanctioned discrimination) is also a significant concern for Coptic Egyptians. In practice, there is widespread discrimination against Coptic Christians in many different areas of life. Witnesses consistently testified that non-Muslims are rarely promoted to senior positions within the public service, universities or security forces, in violation of the prohibition on discrimination under international human rights law. Moreover, Copts have historically been under-represented in Egypt’s legislature and other positions of political power.[49] The Subcommittee was told that a Coptic Governor of Quena in Upper Egypt, Emad Shehata Michael, was forced to resign in 2011 in order to keep the peace after ultra-conservative Salafi groups in his region protested the appointment of a Christian Governor by cutting off access to the railway.[50] Furthermore, during Egypt’s first democratic elections in 2011–2012, Coptic politicians were generally accorded low positions on Egyptian party lists, which made it difficult or impossible for them to be elected.[51] The Subcommittee recalls that Egypt’s international human rights obligations and its new constitution prohibit discrimination. Egypt’s government must take steps to end both informal discrimination and any formal legal or administrative measures that discriminate against Copts or others on the basis of their religion, belief or status.[52] The Subcommittee wishes to underscore that Copts participated in Egypt’s revolution equally with their Muslim compatriots and yet, even after the fall of the Mubarak regime, Copts continue to face discrimination in their day-to-day life, which denies them the human rights enjoyed by other Egyptian citizens. Human Rights Violations in the Context of Family LifeAs noted above, with respect to matters of personal status, such as marriage, divorce, child custody, burial, and inheritance, Egypt’s new constitution provides to Muslims, Christians and Jews the right to be governed by their own religious law. Professor Brown noted, however, that this has been “Egyptian practice for decades and even centuries.” He explained that “when you get married, divorced, or inherit as an Egyptian, you do so based on which religious community you are a part of.”[53] The Subcommittee was told, however, that Egyptian law applies Islamic legal principles to govern inter-faith marriages involving one Muslim spouse. Witnesses informed the Subcommittee that as a result, Egyptian family law disadvantages Christian spouses and children and violates their rights to freedom of religion and non-discrimination.[54] Witnesses stressed that Egyptian personal status laws place Coptic women in a particularly difficult position because they face discrimination on the basis of both gender and religion, in violation of Egypt’s obligations under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which guarantees equality for men and women in marital and family relations.[55] Professor Brown explained: The fact is that Islamic personal status law is a gendered law. You have different rights according to whether or not you are male or female. That is something that is very hard for [the Muslim Brotherhood and President Morsi’s government] to get around, and something that they regard as based on divine instruction, and not the sort of thing that the United Nations should be telling them not to do.[56] According to witnesses, Egyptian women, including Coptic women, are also subject to high levels of violence in the domestic sphere and lack legal protection from marital rape.[57] The Subcommittee was informed that in Egypt, marriages between Muslim women and non-Muslim men are effectively prohibited. If a Muslim woman is found to be married to a non-Muslim man, that woman would be considered by many to have committed apostasy. In the past, the Egyptian government and courts have adopted an interpretation of Islamic law dictating that any children from such a marriage may be removed from the custody of their parents and instead placed in the custody of a male Muslim guardian. Moreover, Egyptian law provides that a non-Muslim woman who converts to Islam must divorce her husband if he is not Muslim. Custody of any children is then awarded to the now-Muslim mother. In both circumstances, and if a husband converts to Islam but his wife does not, the children of these marriages would be identified as Muslims by the state without regard to the wishes of both parents, and could be required to practice that religion. Any children of such unions who identify as Christian face discrimination and possibly even persecution.[58] According to one witness, “forced conversion of Christian minors when one of their parents converts to Islam is not only discriminatory, it is an attack on the rights of the child.”[59] The Subcommittee notes, in this regard, that international law guarantees the right of both parents to contribute to their children’s upbringing in accordance with their religious beliefs, and requires states to respect children’s freedom of religion or belief “in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.”[60] Egypt must also ensure that Copts, including Coptic children, in community with other members of their group, are able to enjoy their own culture and profess and practice their own religion.[61] The Right to Take Part in Cultural Life

Mr. Nabil Malek, President, Canadian Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, informed the Subcommittee that the history and contribution of the Coptic Christian Orthodox community, which has existed in Egypt for close to 2,000 years, is not included in the country’s history books and that the Coptic community is not officially acknowledged as an integral component of Egyptian society and culture.[62] The Subcommittee notes that international human rights law and standards require that Coptic Christians be able to participate fully and contribute to the country’s cultural life. Moreover, by ratifying the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Egypt has committed to ensuring that its education system promotes “understanding, tolerance and friendship among all … racial, ethnic and religious groups.”[63] Professor Brown indicated that since the revolution, “public life is taking on an increasingly Islamic flavor.” Although the environment is not oppressive towards Christians, he suggested that as a result, “media and perhaps state organizations … may not be friendly or open to them.”[64] The Subcommittee is concerned that the long-term failure to acknowledge the Copts’ historic presence in Egypt and their contribution to Egypt’s history and civilization may have facilitated the emergence of a culture of suspicion and intolerance in some segments of Egyptian society. The increasing marginalization of Copts in the public sphere can only serve to aggravate this situation and plays into the hands of extremist groups.[65] Respect for the Rights of Other Faith CommunitiesAlthough the evidence received focused primarily on the situation of Coptic Egyptians, the Subcommittee notes that Egypt formally recognizes only three religions: Islam, Judaism and Christianity. Disturbing reports were presented during the study of violations of the right to freedom of religion of adherents of other sects of Islam (including Shi’ites, Ahmadis and Qur’anists), Baha’is, as well as individuals who practice non-orthodox versions of Christianity, the few remaining Jews in the country, and “people who have peacefully expressed views critical of religion.”[66] Examples of problems faced by Egypt’s Shi’ite and Baha’i communities illustrate these points. The Subcommittee was informed that a Shi’ite man in Egypt was reportedly arrested and charged with contempt of religion and desecration of a mosque for praying according to the rites of the Shi’ite faith and “representing Shi’ite viewpoints.” In the face of pressure from her family, his wife divorced the man.[67] Furthermore, while parties promoting a political ideology linked to Sunni Islam were permitted to register to participate in Egypt’s 2011–2012 parliamentary elections, a Shi’ite political party was reportedly denied registration.[68] The Subcommittee was informed that Baha’i spiritual assemblies and institutions were dissolved in 1960, and adherents of the Baha’i faith “are subject to harassment, discrimination and detention, in violation of the constitution and international human rights.”[69] According to Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab, the Egyptian Minister of Education recently stated that Baha’i children can attend public schools, but will be required to attend either Christian or Muslim religious education classes. Like Coptic Christians, other minority religious groups also have been the targets of hateful rhetoric from Muslim extremists, which authorities have taken few steps to counter.[70] The Subcommittee recalls that respect for the right to freedom of religion or belief extends not only to those religions recognized by the state, but also to adherents of unrecognized religions. Administrative measures and procedures such as those discussed above constitute important violations of the right to freedom of religion. Finally, international human rights law requires Egypt to take steps to protect minority religious communities, like all citizens, from violence and hateful speech that incites it. Increasing Violence Against the Coptic Community Since the Fall of Former President MubarakAs discussed above, Egyptian authorities have failed to respect or protect Coptic Christians’ rights to freedom of religion, freedom from discrimination, and other human rights for many years. This situation has worsened since Egypt’s revolution in 2011.

Since the revolution, the security situation in Egypt has deteriorated significantly and the government of President Morsi appears uncertain as to whether it has the tools to address these concerns. To date, witnesses indicated that Egypt’s government and institutions have been unable to find a way to restore security in a manner that is appropriate in a democratic society. Egypt’s security forces, which are deeply implicated in past human rights abuses and distrusted by large portions of the population, are barely functioning. The Subcommittee was told that in this context, minority groups tend to be the most exposed to violence and human rights violations.[71] Of particular concern is the fact that extremist groups are exploiting this period of uncertainty to flex their muscle and make a political statement, while those with an interest in re-establishing authoritarian rule attempt to control and limit democratic change.[72] Coptic Christians reportedly have been the victims of violence allegedly perpetrated and/or orchestrated by both groups. The Rights to Life and Security of the Person: Attacks on Copts by Individuals and GroupsEvery witness who appeared before the Subcommittee stressed that the failure of the state to ensure the security of all Egyptians, including Copts, was an overriding concern. Information provided to the Subcommittee by Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab indicates that incidents of sectarian violence were increasing prior to the 2011 revolution and that this trend has continued since.[73] Amnesty International Canada informed the Subcommittee in December 2011 that “during the past three decades Egypt has witnessed some 15 major attacks against Copts, but in the past ten months alone ... there have been at least six attacks on churches and/or clashes between Muslims and Copts.”[74] Violence continued throughout 2012 and into 2013.[75] While it is often extremists who instigate violence, witnesses expressed the view that the Egyptian authorities routinely fail to protect members of the Christian minority. For example, in late September 2012, in the context of wider instability resulting from confrontations between Egyptian authorities and violent religious extremist groups, many Coptic families in the city of Rafah in the Sinai Peninsula fled their homes in the face of threats of violence and even death from the extremists.[76] In January 2013, Egyptian security forces reportedly foiled an attempted bombing of the Rafah Church.[77] Sectarian violence also has had a tendency to erupt as a result of feuds between individuals from the Coptic and Muslim communities. According to witnesses, such violence is often rooted in negative stereotypes and inequality between the two groups. In his testimony before the Subcommittee, Mr. Malek argued that the Copts’ exclusion from cultural life, along with long-standing laws, policies and practices that violate Copts’ freedom of religion, and significant levels of discrimination in Egyptian society, have created “a culture that the masses in the street cannot but follow.”[78] For example, violent attacks by neighbours following disputes between Christians and Muslims recently forced a number of Copts living in Alexandria and in the village of Dahshour, near Cairo, to flee from their homes.[79] In Dahshour, for example, the violence reportedly began after a Muslim customer became angry that a Coptic laundry employee had burned his shirt while ironing it.[80] In this context, the Subcommittee notes with concern two outbreaks of sectarian violence between Muslims and Coptic Christians in April 2013 — first in the town of Khosus, and then outside St. Mark’s Cathedral, the main Coptic Cathedral in Cairo.[81] According to One Free World International, “[p]olice and security forces typically do not come to the assistance of religious minorities and often charge the victims if they try to lay a complaint.”[82] Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab told the Subcommittee that when an angry mob attacked the home of a Coptic atheist named Albert Saber and his mother called the police, it was Mr. Saber who was arrested for defamation of religion. The police permitted the mob to beat Mr. Saber as they brought him out of his house and failed to protect him from other inmates in the police detention facility, where he was severely beaten. According to Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab, Mr. Saber was tried and convicted; he is now serving a three-year prison sentence.[83] The fact that the perpetrators of acts of discrimination and violence against Copts and other minority belief communities have not consistently been held accountable for their actions exacerbates existing tensions and allows religious violence to occur in an environment of impunity. Witnesses informed the Subcommittee that so-called “reconciliation” talks between Christian and Muslim communities are often convened by authorities in lieu of criminal investigations and prosecutions, including in the aftermath of serious violence against Christians and/or the destruction of churches by angry mobs.

Rarely are individuals legally sanctioned for their crimes. At times, the Egyptian government has responded to violent attacks on Coptic places of worship by ordering the military to rebuild churches after such incidents. However, according to one witness, under the regime of former president Mubarak and since, the Egyptian government’s commitment to ensuring such reparations has been inconsistent.[84] Witnesses informed the Subcommittee that Egyptian authorities have consistently failed to apply the law equally to hold accountable those responsible for violent attacks on Copts. Witnesses expressed the view that sectarian violence in Egypt is often manipulated for political ends. Prior to the fall of former President Mubarak, the “regime’s manipulation of Islamic sentiments in its struggle against Islamists for legitimacy was a key factor” in the recurrence of religiously-motivated violence.[85] Ms. Sherif Abdel Wahab stressed her view that in the post-revolutionary context, violence is being orchestrated against political opponents ostensibly in the name of protecting the Islamic religion.[86] The Subcommittee stresses that it is a fundamental principle of international human rights law that states have an obligation to protect the rights of all people under their jurisdiction without discrimination on the basis of religion or belief. This responsibility includes preventing and punishing acts of violence and discrimination committed by private individuals or groups. Any failure to investigate and bring to justice those responsible for attacks against Coptic Christians in a consistent manner is a violation of Egypt’s international obligations.[87] It must also be noted that the security forces in post-revolutionary Egypt are made up largely of the same personnel that served under successive oppressive regimes. Egypt’s security forces urgently need to be reformed and re-trained to view their core function as the maintenance of security in the interests of the people of Egypt, rather than the maintenance of security in the interests of the state, the military or the government. In the Subcommittee’s view, a shift towards a policing model that is appropriate for a democratic society will be particularly important with respect to ensuring the protection of Copts and other religious minorities. The Rights to Life and Security of the Person: Attacks by Security PersonnelThe Subcommittee recalls that it is the Government of Egypt’s responsibility to protect and uphold the rights of its religious minorities. It is a matter of great dismay to the Subcommittee that on numerous occasions, security forces reportedly have not only failed to protect Coptic Christians but, at times, themselves have been the perpetrators of these acts of violence.

On October 9, 2011, Coptic Christians had gathered in Cairo’s Maspero Square to protest the earlier destruction of a church and to demand full respect for their human rights, including their right to freedom of religion. What started as a peaceful protest turned violent. There are conflicting accounts as to how the violence began. Nonetheless, the military responded with what has been deemed by international human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, to be excessive force, killing 26 Copts and one Muslim in addition to wounding 321 people.[88] One soldier was also killed in the incident. According to Amnesty International, Egypt’s human rights commission — the National Council for Human Rights — concluded that three armoured personnel carriers drove through the crowd killing a number of demonstrators.[89] Although the Council was unable to confirm whether or not live ammunition was used, DFAIT officials informed the Subcommittee that eight protestors were killed by gunfire.[90] The Right to an Effective Remedy for Human Rights Violations and AbusesThere has been much controversy with respect to the investigation launched by Egyptian authorities into the Maspero incident. Two parallel judicial processes, one civilian and one military, have taken place. In the civilian trial, two Copts were reportedly convicted of stealing military weapons during the protest. In the military trial, three soldiers were convicted of involuntary manslaughter and were sentenced to two to three years imprisonment for killing 14 demonstrators. According to DFAIT, the sentence for involuntary manslaughter could range from one to seven years in prison in the case of an act that causes the death of more than one person. The court found that the soldiers were guilty only of “negligence and an absence of caution while they were driving armed forces armoured personnel carriers in an arbitrary fashion, leading to them striking the victims”, which may be why their sentences were on the lower end of the range.[91] The Subcommittee is dismayed by this outcome. Even more concerning is the fact that no cases have been brought forward regarding the eight protestors who were killed by gunfire. At this time, no senior officers have been held accountable for their possible role in the incident, although the Subcommittee was told that Field Marshal Tantawi, former chief of staff Sami Anan, former military police head Hamdy Badeen, and current military police head Ibrahim El-Domiaty will be investigated regarding their possible involvement.[92] Witnesses questioned the ability of the military to investigate itself objectively.[93] This lack of confidence comes as no surprise, considering that the country’s security forces have been held accountable only rarely for acts of violence against the civilian population before, during or after the Mubarak era. In fact, for 45 years (1967–2012), Egypt was under a state of emergency, giving its security forces sweeping powers of arrest and detention and providing for court proceedings before tribunals that lacked basic guarantees of independence and impartiality, leading to unfair trials.[94] The Need to Ensure the Rule of LawWitnesses emphasized that the rule of law is critically weak in Egypt during this time of political instability, and that the whole environment has become more insecure. Protestors, both Christian and Muslim, are being attacked, detained, tortured, have disappeared and at times, been killed, by both state and non-state actors.[95] A Christian leader has emphasized that “in … (Egypt’s) peace and security Christians will find their peace and security.”[96] Other witnesses shared this perspective.[97] Yet, the Subcommittee was told that there is no particular actor or institution within the Egyptian state that Christian communities can call upon in order to enforce their rights as Egyptian citizens.[98]

Mr. Lotfy, of Amnesty International, reminded the Subcommittee that the security forces have not been reformed and many of the repressive laws that enabled decades of misrule by previous Egyptian leaders remain in force. The Maspero Square incident is part of a broader pattern of killings of demonstrators and excessive use of force by security personnel policing demonstrations.[99] The country’s security forces also have been accused of torture and sexual violence.[100] Mr. Malek expressed the view that the Maspero Square incident was closely connected to larger power struggles in the country and efforts by the military to retain and regain their power and influence “by manipulating Islamic sentiments.” He argued that at Maspero, the military “hit the Coptic minority hard to scare the majority.”[101] He also stressed that Coptic Christians make a convenient target for both sides in the power struggles now playing out between Muslim extremists and authoritarian forces in the country.[102] Mr. Hutchinson told the Subcommittee that some Christian leaders in Egypt are wary of efforts by foreign governments to advocate on their behalf, since those opposed to the Christian minority have often cited such efforts as ‘proof’ that Christians are a “‘foreign element’ in Egypt, or worse, agents of foreign interests.”[103] The Egyptian state is a vast apparatus in itself. The extent to which Egypt’s civilian government can effectively exercise control over Egypt’s powerful military, and to a lesser extent over the Ministry of the Interior (which includes the police), remains unclear. Moreover, reforming the methods and changing the mindsets within the ranks of the military, the intelligence services and the police, as well as the bureaucracy will be a significant challenge going forward. The Subcommittee is pleased to report, therefore, that it has been assured by officials at DFAIT that “Canada will continue to support efforts by the Egyptian government to move towards full and meaningful transition to civilian, democratic rule, which includes civilian oversight of the military.”[104] The Subcommittee notes with concern that it remains unclear whether Egypt’s civilian government intends to prioritize bringing to justice those within state institutions who are responsible for human rights violations.[105] The Subcommittee believes that it is imperative that the Government of Egypt take steps to ensure security for all those within its borders, regardless of their religious faith, and to punish all those who abuse and violate the human rights of others. A society that professes to be governed by the rule of law can permit no less. Professor Brown suggested that in addition to taking steps to bring human rights violators to justice, Egypt needs to review all of its legislation to bring repressive laws enacted under the previous regime into compliance with international human rights standards.[106] The Subcommittee hopes that the Government of Egypt will conduct such a legislative review in the near future. Finally, while the Subcommittee takes note of the view that Egypt’s judicial institutions remain functional, it is very concerned at reports that courtrooms have repeatedly been stormed, court hearings broken up, and attempts made to intimidate judges. Judicial independence and a functioning court system are indispensable components of the rule of law.[107] As such, they are necessary to the protection of the rights of Copts and other Egyptians. Other Human Rights ConcernsRespect for Women’s Human Rights

Deteriorating respect for the human rights of Egyptian women is another subject of serious concern to the Subcommittee. The Subcommittee wishes to note its agreement with the sentiment expressed by Canada’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Honourable John Baird, when he said: “If we want fewer extremist governments, we need the active participation of women in all aspects of society.”[108] While half of the population of Egypt is female, the Subcommittee was dismayed to learn that only 8 women were included in the 100-person Constituent Assembly that drafted the Constitution, a number of whom resigned between September and November 2012 in protest against the Islamist-dominated drafting process. In their testimony, witnesses from Amnesty International and the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies highlighted the fact that Egyptian women have not been able to participate in Egypt’s democratic transition on an equal basis with men, and informed the Subcommittee that the inclusion of adequate guarantees of gender equality in Egypt’s future legal order are seriously threatened.[109] The evidence that the Subcommittee received also indicates that sexual violence and harassment are being used by extremist elements of Egyptian society to intimidate and silence women who express different political views — just as sectarian violence is in some instances being instigated against Coptic Christians for political gain. Reportedly, there has been little follow-up by authorities in relation to reports of these types of violent crimes against women.[110] According to Mr. Malek, a number of Coptic women have been abducted by extremist Islamic organizations, raped, and then pressured into marrying their captors and converting to Islam. He indicated that such incidents are rarely investigated by police and impunity is said to be the norm.[111] The UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief has highlighted his position that such actions violate women’s right to be free from forced conversion, which is an aspect of their right to freedom of religion, as well as their right to security of the person. Furthermore, the Special Rapporteur has stated that continued impunity gives “the impression that law enforcement agencies systematically fail to provide effective protection for women and girls.”[112] The Subcommittee is proud of Canada’s record of speaking out forcefully in favour of the human rights of women on the international stage. The Subcommittee wishes to reiterate, once again, that all people, including women and members of religious minorities, benefit equally from internationally protected human rights. As the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reminds us, these rights are inalienable and spring from the inherent dignity of the human person. Women’s ability to enjoy their human rights on an equal basis with men may not be restricted or violated in the name of religion, culture or tradition. Women were full participants in Egypt’s revolution and must have the opportunity to contribute equally to building a democratic, tolerant and prosperous country. Increasing Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Association

Increasing legal restrictions on freedom of expression and association are also a matter of concern. A proposed new NGO law that would place non-governmental organizations, including human rights advocacy groups, under government control; the continuing criminalization of blasphemy; and a series of criminal complaints made against individuals who are publicly critical of President Morsi or his government all raise serious concerns about the commitment of Egypt’s current leaders to ensuring that the law is applied equally to all, and not deployed selectively to serve the interests of a particular political group.[113] Open public discussion and debate is also vital if freedom of religion or belief is to thrive in a society. The freedom to meet, discuss and share ideas with others also is crucial to ensuring respect for human rights more generally. The Subcommittee stresses, therefore, the importance of Egypt’s international obligation to respect the rights to freedom of expression and association, including the right to defend human rights. The Road Ahead: Fulfilling the Promise of the Arab Spring?The Subcommittee was informed that, for the first time, a new generation of Coptic activists is insisting publicly on a conception of Egyptian citizenship that looks past religious affiliation.[114] Nevertheless, although Copts stood shoulder to shoulder with their Muslim compatriots in Tahrir Square to bring their country into a new era of democracy, it is not clear where their place will be in the new Egypt. Copts in Egypt remain fearful for their future.

On his 100th day in office, President Morsi said that, “any assault on Copts is an assault on me.”[115] However, despite the President’s pledge to ensure the security of all Egyptians, sectarian violence has continued. In April 2013, violence broke out around St. Mark’s Coptic Cathedral between groups of Christians and Muslims, and police reportedly fired tear gas into the Cathedral compound.[116] The Subcommittee welcomes President Morsi’s condemnation of this incident as well as his stated commitment to investigate the events which led up to the violence. This commitment needs to be followed up with action. The Subcommittee wishes to stress that people of different faiths have lived together peacefully in Egypt for hundreds of years. DFAIT officials assured the Subcommittee that an overwhelming majority of Egyptians support religious tolerance. Under successive regimes, the political movement with which President Morsi is affiliated, the Muslim Brotherhood, and other organized groups, endured repression that included arbitrary arrest and detention and even torture, as well as violations of their rights to freedom of expression and political liberties. Therefore, it is hoped that the administration of President Morsi, bearing in mind its own experience with repression, will uphold its commitment to ensuring equality and dignity for all the people of Egypt, regardless of their religious faith, gender or other characteristics.[117] It is clear that the success of Egypt’s democratic reforms over the long term will depend on several key factors. Changing the way in which state institutions and the security forces interact with religious minority communities is vital, as is leadership from the top on religious tolerance and equality. At the same time, a sustained effort at changing mind-sets at a grass-roots level will also be required if social change is to take hold. Canadians place great importance on respect, without distinction, for the human rights of all people. Canada should continue to support President Morsi and the Government of Egypt in fulfilling their commitment to protect equally the security and religious liberty of all Egyptians, including Copts. The Subcommittee believes that the Government of Canada should also continue to remind the Egyptian government of its obligation to uphold the rule of law, including by bringing to justice the perpetrators of acts of sectarian violence –– regardless of their political or institutional affiliation. Where these obligations are not met, Canada should continue to speak out in favour of human rights in a strong and principled manner. The Subcommittee observes that the Government of Canada will need to communicate with the Coptic community and others, including especially Islamic leaders who support religious tolerance, to ensure that Canadian support for human rights is offered in a manner that will be effective in the complex environment of post-revolutionary Egypt. Over 60 years ago, in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the nations of the world committed themselves to upholding the dignity and worth of the human person, affirming that “it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law.”[118] For decades, Egypt’s rulers failed to live up to this pledge and the people of Egypt suffered. Finally, in early 2011, Egyptians rebelled, united despite religious differences. It is the Subcommittee’s hope that in charting its country’s course for a democratic future, the Government of Egypt will ensure that the human rights of all Egyptians, regardless of faith, are effectively protected. The Subcommittee firmly believes that religious intolerance, discrimination, extremism, and violence have no place in the new Egypt. The Subcommittee will continue to monitor developments in the country, particularly with respect to freedom of religion or belief –– an issue of importance to this Parliament and to Canadians as a whole. RecommendationsThe Subcommittee therefore recommends: RECOMMENDATION 1 That the Government of Canada, at every appropriate opportunity, call upon the Government of Egypt to:

RECOMMENDATION 2 That the Government of Canada continue to monitor closely the treatment of the Coptic minority in Egypt and continue to raise issues of religious freedom and discrimination in all appropriate forums, including bilateral and multilateral human rights dialogues. RECOMMENDATION 3 That the Government of Canada, through its Embassy and government offices in Egypt, continue to develop relationships with key religious leaders, and where appropriate and in consultation with such leaders, undertake diplomatic and other visits to areas where the human rights of religious minorities are allegedly being infringed. RECOMMENDATION 4 That the Government of Canada continue to be consistent in condemning all serious incidents of sectarian violence in Egypt and continue to press for effective, independent and impartial investigations, with appropriate consequences for perpetrators and adequate remedies for victims, when such attacks occur. RECOMMENDATION 5 That the Government of Canada continue to call upon the Government of Egypt to ensure the safety of peaceful demonstrators during public protests and to thoroughly, independently and impartially investigate all violent attacks on human rights defenders and protestors, including incidents of sexual violence, with a view to bringing to justice those responsible. RECOMMENDATION 6 That the Government of Canada, through its embassy, continue to meet regularly with Coptic activists, Egyptian human rights defenders and NGOs, and provide appropriate diplomatic support in order to empower them in their fight for human rights in Egypt. RECOMMENDATION 7 That the Government of Canada and Canada’s Office of Religious Freedom explore avenues for engaging with like-minded academic institutions and the Al-Azhar Institution on matters relating to respect for freedom of religion or belief and inter-faith dialogue. RECOMMENDATION 8 That the Government of Canada continue to ensure that all of its Canadian and locally-engaged employees in North Africa and the Horn of Africa region understand the situation facing Coptic Christians in Egypt and ensure their sensitivity to those who may need to seek asylum in Canada. RECOMMENDATION 9 That the Government of Canada urge the Government of Egypt to re-build state institutions such as the military, the police and other security services on a non-sectarian basis, to take steps to ensure that the judiciary and prosecution services become more representative of the religious and cultural diversity of the country, and to make the principle of non-discrimination an integral part of the operational culture of the Egyptian bureaucracy. RECOMMENDATION 10 That the Government of Canada call upon the Government of Egypt to reform the training and education received by its security forces in order to promote respect for human rights and democracy, including training on international standards regarding the use of force and democratic policing, as well as on principles of non-discrimination and the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. RECOMMENDATION 11 That the Government of Canada consider favourably any reasonable request from Egyptian authorities for technical assistance aimed at promoting respect for human rights and democratic practices, including the principles of non-discrimination and freedom of religion. RECOMMENDATION 12 That the Government of Canada continue to call upon the Government of Egypt to protect women’s human rights and to ensure that women participate fully in all aspects of the country’s democratic transition, and that through its Embassy in Cairo, the Government of Canada continue to support Egyptian women, including Coptic women, to organize peacefully in order to claim their rights. RECOMMENDATION 13 That the Government of Canada call upon the Government of Egypt to live up to its commitments in respect of other internationally protected human rights, including but not limited to:

RECOMMENDATION 14 That the Government of Canada, in its development assistance to Egypt, consider continuing programming that aims to generate economic opportunities for Egyptians, particularly Egyptian youth. [1] Minutes of Proceedings, Meeting No. 6, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 3 November 2011. The House of Commons Subcommittee on International Human Rights [SDIR] decided to narrow the scope of its report to the situation of Coptic Christians in Egypt only. [2] Evidence, Meeting No. 48, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 2 October 2012 (Mark Bailey, Director General, Middle East and Maghreb Bureau, Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade [DFAIT]). [3] DFAIT, Response to Questions Taken on Notice, 15 October 2012; “Egypt Profile,” BBC, 7 March 2013; “Timeline: Revolution in Egypt,” 19 June 2012, Los Angeles Times. [4] DFAIT, Response to Questions Taken on Notice, 15 October 2012. [5] Ibid. [6] Salafis favour a literal interpretation and application of their understanding of religious teachings: Evidence, Meeting No. 73, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 21 March 2013 (Nathan Brown). [7] Evidence, ibid. Problems with the drafting process are discussed in Nathan J. Brown, “Egypt’s Constitution Conundrum,” Foreign Affairs, 9 December 2012. [8] These withdrawals were widely reported in Egyptian news media, including in: “Egyptian churches withdraw from Constituent Assembly,” Egypt Independent, 17 November 2012; Basil El-Dabh, “Press Syndicate withdraws from the Constituent Assembly,” Daily News Egypt, 20 November 2012; Heba Fahmy, “Wave of walkouts leaves Constituent Assembly in Islamists’ Hands,” Egypt Independent, 21 November 2012. [9] UN News Centre, “UN human rights chief calls on Egypt’s president to roll back powers of recent decree,” 30 November 2012. [10] Evidence, Meeting No. 70, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 5 March 2013 (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab, International Advocacy Officer, Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies). [11] “Egypt crisis: Morsi offers concession in decree annulment,” BBC, 9 December 2012. [13] “Egypt’s President Morsi hails constitution and urges dialogue,” BBC, 26 December 2012. [15] Ibid. [16] Ibid. [17] Evidence, Meeting No. 70, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 5 March 2013 (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab). [19] Toni Johnson, “Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood,” Council on Foreign Relations, 25 June 2012. The Muslim Brotherhood is not listed as a terrorist organization by Canada: Public Safety Canada, Currently listed entities. [20] Evidence, Meeting No. 48, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 2 October 2012 (Mark Bailey). See also Evidence, Meeting No. 73, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 21 March 2013 (Nathan Brown). [21] See, e.g.: Johnson, “Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood,” Council on Foreign Relations, cited above, and “Muslim Brotherhood Statement Denouncing UN Women Declaration for Violating Sharia Principles,” 14 March 2013, Ikhwanweb The Muslim Brotherhood’s Official English website. [22] Evidence, Meeting No. 48,

1st Session, 41st Parliament, 2 October 2012 (Mark

Bailey); Evidence, [23] Ibid. (Nathan Brown). [25] Ibid.; Evidence, Meeting No. 70, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 5 March 2013 (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab). According to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, Qu’aranists are a “tiny group” that “accepts only the Qur’an as the sole source of religious guidance” (U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, “Egypt,” Annual Report 2012). [26] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), art. 18; Convention on the Rights of the Child, art. 14 [CRC]. Both Canada and Egypt have ratified the ICCPR and the CRC. [27] One Free World International, Egypt at the Crossroads: Standing Up for those Left Behind in the Wake of Egypt’s “Arab Spring,” Canada’s duty to Act in Support of Religious Minorities, A Report and Recommendations by One Free World International, Presented to the Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, November 2011, p. 7. [28] Evidence, Meeting No. 9, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 22 November 2011 (Reverend Majed El Shafie, [29] An unofficial translation of article 33 of the 2012 Constitution states: “All citizens are equal before the law. They have equal public rights and duties without discrimination.” Article 9 of the 2012 Constitution states: “The State shall ensure safety, security and equal opportunities for all citizens without discrimination.” (Nariman Youssef, “Egypt’s Draft Constitution Translated,” Egypt Independent, 2 December 2012). An unofficial translation of article 40 of the 1971 Constitution provides that “All citizens are equal before the law. They have equal public rights and duties without discrimination on grounds of race, ethnic origin, language, religion or creed” (Egypt State Information Service, Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 1971). Egypt’s international human rights obligations require that all individuals under the state’s jurisdiction benefit from the right to equality before the law (ICCPR, arts. 2, 26). Egypt’s 2012 and 1971 constitutions extend the right only to citizens. [30] Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, Religious Freedom in Egypt: The Case of the Christian Minority, June 2009, p. 4, submitted to SDIR; Clark B. Lombardi and Nathan J. Brown, “Do Constitutions Requiring Adherence to Shari’a Threaten Human Rights? How Egypt’s Constitutional Court Reconciles Islamic Law with the Liberal Rule of Law,” American University International Law Review, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2006, p. 390. The original text of the 1971 Constitution stated that “the principles of the Islamic shari’a are a chief source of legislation.” In 1980, the word “a” was removed and replaced with the word “the”. [31] Evidence, Meeting No. 10, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 24 November 2011 (Don Hutchinson, Vice President and General Counsel, Religious Liberty Commission, Evangelical Fellowship of Canada); Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, Religious Freedom in Egypt, p. 5. [32] Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, Religious Freedom in Egypt, p. 4. See also, One Free World International, Egypt at the Crossroads, p. 9, indicating that international law does not allow Egypt to make its adherence to international human rights obligations conditional on conformity to Islamic law. [33] Evidence, Meeting No. 7, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 15 November 2011 (Ashraf Ramelah, President and Founder, Voice of the Copts, and Nabil Malek, President, Canadian Egyptian Organization for Human Rights); Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, Religious Freedom in Egypt, pp. 3-5; Evidence, Meeting No. 13, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 6 December 2011 (Alex Neve, Secretary General, Amnesty International Canada). [34] Evidence, Meeting No. 70, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 5 March 2013 (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab). [35] Ibid.; Evidence, Meeting No. 73, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 21 March 2013 (Nathan Brown); Human Rights Watch, “Egypt: New Constitution Mixed on Support of Rights,” 30 November 2012. [37] Ibid. (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab). [39] Ibid. [40] Nabil Malek, The Persecution of Egypt’s Copts: Causes and Solutions, A Brief presented to the Subcommittee on International Human Rights, House of Commons, Canada, Canadian Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, November 2011, p. 4; Amnesty International, Broken Promises: Egypt’s Military Rulers Erode Human Rights, November 2011, pp. 39-40, submitted to SDIR by Alex Neve; Evidence, Meeting No. 10, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 24 November 2011 (Don Hutchinson). [41] Evidence, Meeting No. 7, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 15 November 2011 (Nabil Malek); Ibid. (Don Hutchinson); Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, Religious Freedom in Egypt, pp. 11-12; Evidence, Meeting No. 13, 1st Session,41st Parliament, 6 December 2011 (Alex Neve); Evidence, Meeting No. 34, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 1 May 2012 (Mohamed Lotfy, Researcher, Amnesty International); Evidence, Meeting No. 70, 1st Session, 41st Parliament, 5 March 2013 (Nadine Sherif Abdel Wahab). [42] Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 22: The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion (Art. 18), 1993, UN Doc. CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, para. 4. [43] One Free World International, Egypt at the