CIMM Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

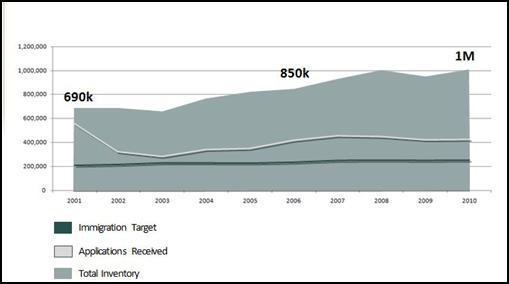

Canada is in the enviable position of attracting more prospective immigrants than the Government plans to admit. Minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism, the Honourable Jason Kenney, testified to the Committee that Canada is “the most desirable destination in the world. In fact, last year Ipsos Reid did a global poll, from which they estimated that at least two billion people around the world would like to emigrate to Canada right now.”[1] This popularity causes challenges for policy-makers, who are charged with ensuring that immigration to Canada meets its multiple goals, including benefit to Canada’s economy and meeting labour market needs, family reunification, and humanitarian assistance. The Government also has to make sure that Canada’s immigration system is efficient and, as stated in the enabling legislation, able “to deliver on immigration goals by means of consistent standards and prompt processing”.[2] An efficient immigration system is of national importance, especially as future labour force growth is going to depend almost entirely on immigration. Indeed, immigration is a vital component of a multi-pronged strategy to address Canada’s looming demographic challenges, including labour shortages in certain sectors. In this context, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration undertook a study of immigration application backlogs and the Government’s Action Plan for Faster Immigration, a legislative change to address these backlogs. There are more than a million people awaiting a decision on their immigration file. As of July 2011, the backlog included, among others, 450,000-460,000 economic class applicants in the Federal Skilled Worker (FSW) program and 165,000 family class applicants in the parents and grandparents sponsorship program. Officials from Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) estimate, that barring any changes, the backlog in Federal Skilled Worker applications will be eliminated by 2017, due to previous Ministerial Instructions.[3] In the parent and grandparent category, however, officials stated that, barring any changes, the backlog would grow to 350,000 by 2020 and these prospective immigrants could experience a wait time of 15 to 20 years.[4] These figures indicate a problem situation that is clearly unsustainable and in need of attention. The report begins with a history of how immigration application backlogs formed and how immigration is managed in Canada through the annual Immigration Levels Plan. It then turns to recent initiatives to address application backlogs, notably the Action Plan for Faster Immigration, implemented in 2008, and the Government’s recent announcement of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification. Witness testimony and the Committee’s recommendations are grouped according to immigration programs, including Federal Skilled Workers, federal investor immigrants, and parent and grandparent family class sponsorship. A number of factors contributed to create the problem of immigration application backlogs facing CIC today. The global increase in the movement of people was felt here in Canada as the number of immigrant applications increased significantly toward the end of the 1990s: between 1997 and 2000, the number of immigrant applications in all classes increased by 46%. By 2002, the inventory of Federal Skilled Worker cases totalled over 170,000 cases involving more than 400,000 people.[5] When it came into force in 2002, under the previous government, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) required that all applications be processed to a final decision. This legislative change created the conditions that, if applications for permanent residency exceeded the number of admissions in any given year, a backlog was inevitable. This is in fact what happened. Over the period 2006 to 2010, an average of 436,208 new applications for permanent residence were received annually, while the immigration target range for most of that period was 240,000 to 265,000. (see Table 1) Table 1: Permanent Resident Applications Received and Approval Rate [6]

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, CIC Operational Network at a Glance, CIC Operational Databases, 2nd Quarter 2011. Applications in excess of the immigration target accumulate, unopened, and form a backlog. Figure 1 shows the number of permanent resident applications received relative to the immigration target and the subsequent backlog that developed over the last decade.

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, http://www.cic.gc.ca/ftp/20111020-eng.asp The backlog of Federal Skilled Worker applications was exacerbated by a court challenge to the original transitional provisions of IRPA. This resulted in “dual assessment” of Federal Skilled Worker applications, using either the selection criteria of the former Immigration Act or the IRPA, whichever evaluation would have been more favourable to the applicant. The litigation and redress added to processing times. Not all immigration categories have a backlog. Temporary resident visas issued to visitors, students, and temporary workers, for instance, are placed directly into processing upon receipt. Family class sponsorships of spouses, partners, and children are also placed directly into processing, though processing times may vary up to two years.[7] However, in some immigration categories, notably Federal Skilled Workers, parents and grandparents, and federal investors, the backlog is substantial. Table 2 shows the backlog for the major categories of permanent residents as of July 1, 2011. Table 2: Permanent Resident Inventory as of July 01, 2011 (Persons)

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, the Most Recent Inventory Period: dwsweb;(4) International Region/IMM_caips_e from download of July 1, 2011. * By virtue of the Canada-Quebec Accord Relating to Immigration, the Quebec government is responsible for selecting immigrants destined to the province. The federal government has entered into agreements with the other provinces and territories that allow them to select a certain number of economic class immigrants as well. Backlogs hinder Canada’s realization of immigration policy goals, such as family reunification and benefit to the Canadian economy. The backlog in Federal Skilled Worker applications has made it difficult to match workers with the skills in demand in the Canadian economy and dampened Canada’s attraction as a destination. Further, as one witness stated, “until you get rid of the backlog, you're not going to be able to manage the immigration program effectively.”[8] Table 3: 2012 Plan Admissions Ranges

Source: Citizenship and

Immigration Canada, Supplementary Information for the 2012 Immigration Levels

Plan, The federal government develops an annual Immigration Levels Plan, taking into account the practical limits on the number of new immigrants Canadians and governments of all levels wish to settle in Canada. The plan is part of the Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, which must be tabled in Parliament every November. It normally establishes a target range for each category of immigration. The Immigration Levels Plan for 2012 is included as Table 3. The share of immigrants admitted through economic classes has averaged nearly 60% of the total for the last decade. The Federal Skilled Worker program is the flagship program within this class; established in 1967 with the purpose of selecting immigrants with certain economic attributes to fill gaps in the Canadian labour market. Prospective federal skilled workers are assigned points for different attributes, such as education and language ability and must pass a points threshold. For a number of years in the annual levels plan, the federal government has accorded the provinces and territories the ability to identify workers needed to fill regional labour market needs and to encourage settlement in non-traditional immigrant destinations. As the number of immigrants selected through the Provincial Nominee Program has increased, the number of Federal Skilled Worker immigrants has decreased in the planned mix of immigrants. The economic class also includes investor immigrants and entrepreneurs, selected on the basis of their investments in Canada. Investor immigrants must have: business experience; demonstrate a minimum net worth of $1,600,000 that was legally obtained; and make a $800,000 investment in the Canadian economy. The Entrepreneur Program seeks to attract experienced business persons who will own and actively manage businesses in Canada that contribute to the economy and create jobs. It is important to note that although admissions through the economic class represent nearly 60% of total admissions, the total number of admissions also include spouses and dependents that accompany the principle applicant. In fact, more than half of the admissions through the economic classes are family members and not principal applicants.[9] Through the family class, Canadian citizens or permanent residents may sponsor their spouse, common law partner, conjugal partner, dependent child (including adopted child) or parent or grandparent to become a permanent resident.[10] Family class immigrants have accounted for an average of 26% of annual admissions over the past decade. The Government has determined that sponsorship of spouses, partners, and children takes priority within the family class. These applications are not subject to numerical limits in the Immigration Levels Plan. The Immigration Levels Plan also includes a target for protected persons and resettled refugees. The latter are refugees selected from overseas with the assistance of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) or private sponsors in Canada, who have no other option for a safe and secure future other than resettlement to a third country. Resettled refugees have accounted for about 4.5% of the Immigration Levels Plan over the last decade.[11] The Immigration Levels Plan is developed by the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration in consultation with the provinces and territories and other stakeholders. Factors considered in developing the levels plan include the inventory of immigration applications, resources available, absorptive capacity and settlement funding. After the Immigration Levels Plan is established, CIC operations is responsible for allocating the visas to the more than 90 visa offices around the world. This allocation is reviewed and reassigned as necessary so that, globally, CIC can issue the desired number of visas for a given year. The Immigration Levels Plan interacts with other factors to affect how many people’s applications are processed and how many come to Canada. Other factors include application volumes and the difference between the number of visas issued and number of arrivals. One senior civil servant described some of the factors as follows: The levels plan limits how many people we can welcome to Canada each year. Most years we receive many more applications than can be processed. But again, it's the levels plan that establishes how many people can come in, not processing capacity. This results in the accumulation of backlogs in some categories, which in turn has led to long wait times for some applicants, particularly in the family class.[12] Later on, he said: [S]ince 2008, there is a mechanism that allows us to control the number of new applications. As that is reduced, backlogs and wait times improve because normal processing gradually reduces the total number in the queue. This works whether admissions stay the same or increase. If admissions increase, it happens faster. Simply hiring more officers won't solve the problem, because in the absence of controls, applications accumulate, wait times lengthen, and service standards deteriorate.[13] Later on, he said: Regardless of the levels that are tabled in Parliament, I think managing the intake of applications is critical, to ensure that the number agreed upon is the number that are processed in a timely way so we can get away from this whole notion of backlogs.[14] This overview of the immigration system suggests, as one witness observed, “a few alternatives to preventing a backlog. The Government might take action to, first, increase the number of admissions per year; and/or second, reduce the number of applications; and/or third, increase the number of unsuccessful files”.[15] As outlined in the following section, the federal government has adopted a combination of these strategies. With steady total levels of immigration, the target assigned to different immigration categories within the levels plan also has bearing on application backlogs. The increase in provincial nominees has been accommodated in part by the reduction of Federal Skilled Worker immigrants, meaning fewer annual numbers to reduce the skilled worker backlog. Prioritizing immediate family within the family class leaves less space for parent and grandparent applications in the levels plan to reduce the backlog in that category. The Committee solicited input on the appropriate level and mix of immigrants and heard a range of views. Many were satisfied with the status quo and that is the position adopted by the Committee — we are not recommending a change to total immigration levels or to the mix of immigration categories at this time. A. The Action Plan for Faster ImmigrationThe Government has tried various administrative measures to deal with the backlog of Federal Skilled Worker applications. For instance, CIC contacted applicants in the backlog to offer a fee refund if they chose to withdraw their application. The Department also coded applications so that provinces could select applicants from the backlog for immigration through provincial nominee programs. These measures proved inadequate, in and of themselves, and legislative change was pursued in 2008. At that time, the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration also announced additional administrative measures, including $109 million over five years and reassigning resources to visa posts with large backlogs.[16] The Action Plan for Faster Immigration received Royal Assent as part of the Budget Implementation Act on June 18, 2008. The stated goals of the initiative were to make the immigration system more responsive and flexible, and to address the growth in the backlog. To achieve these purposes, the amendment to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act provided that the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration could issue Ministerial instructions regarding the processing of certain categories of immigration applications, including addressing application intake. The Minister’s authority included issuing instructions that certain applications not proceed for processing, which wasn’t possible prior to the Action Plan. The first set of Ministerial Instructions (MI-1) was published in the Canada Gazette, November 29, 2008, and applied only to Federal Skilled Workers. The instructions stipulated that Federal Skilled Worker applications that met the following criteria would be placed into processing: an offer of arranged employment; applications submitted by Temporary Foreign Workers or International Students residing legally in Canada for at least a year; or applications from skilled workers with at least one year of experience in 1 of 38 prescribed occupations (see Appendix 1). Federal Skilled Worker applications that did not meet one of these initial eligibility criteria were to be returned. Department officials told the Committee that CIC received more applications than anticipated under MI-1 and that a new backlog of 140,000 applications was formed.[17] The 2011 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration indicates that the Department aims to have this backlog cleared up within two years based on additional Ministerial Instructions as outlined in paragraphs to follow. The second set of Ministerial Instructions (MI-2) was published in the Canada Gazette, June 26, 2010 and aimed to limit application intake more successfully. These Ministerial Instructions made further changes to the Federal Skilled Worker stream, reducing the list of eligible occupations from 38 to 29 (see Appendix 2) and introducing a cap on Federal Skilled Worker applications without arranged employment of 20,000, a maximum of 1,000 applications per National Occupation Classification (NOC) code. These instructions also imposed an administrative pause on Investor Class applications, until program amendments came into force. The third set of Ministerial Instructions (MI-3) was published in the Canada Gazette, June 25, 2011 and came into force on July 1, 2011. These Ministerial Instructions again made further changes to Federal Skilled Worker Applications, reducing the cap on Federal Skilled Worker applications without arranged employment to 10,000 annually, with a maximum of 500 per NOC. These instructions also reopened investor class immigration, stipulating a cap of 700 on new immigrant investor applications. Finally, the instructions placed a temporary moratorium on new entrepreneur applications while the program is under review. Ministerial Instructions apply only to new applications. The limit placed on new economic class applications allows CIC to process a combination of backlog applications and new applications every year in order to reach the immigration targets. For instance, with regard to investor class immigrants, immigration officers have been instructed, as a general rule, to process applications in a two-to-one ratio; two older cases from the backlog submitted before June 26, 2010 to one case submitted on or after December 1, 2010.[18] Under the Action Plan for Faster Immigration, progress has been made on addressing the backlog in Federal Skilled Workers — the pre-February 2008 backlog of Federal Skilled Worker applications has been reduced by half, two years ahead of schedule.[19] Had the Action Plan not included a means to address application intake, the backlog in Federal Skilled Worker applications would stand today at over a million and people would be waiting 10 to 12 years to immigrate.[20] The experience with using Ministerial Instructions to address Federal Skilled Worker applications provided important lessons on how to match applications received with the Government’s Immigration Levels Plan and was fine tuned with subsequent usage. B. The Action Plan for Faster Family ReunificationToward the conclusion of the Committee’s study, the Minister announced Ministerial Instructions 4 and measures to address the backlog in parent and grandparent applications, called the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification. The fourth set of Ministerial Instructions (MI-4) was published in the Canada Gazette, November 5, 2011 and came into force that same day. These Ministerial Instructions introduced a pause for up to two years on new applications for sponsorship of parents and grandparents. The instructions indicate that at the end of this temporary pause the program would be re-designed to “prevent a large backlog from growing and be sensitive to fiscal constraints”.[21] Public consultations will provide an opportunity for input into the redesign of the parent and grandparent sponsorship program. Also as part of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification, the Government announced the 2012 immigration target of 25,000 for parent and grandparent sponsorship applications, representing an increase of more than 60% over 2010 admissions (15,324). Parents and grandparents account for 9% of the 2012 Immigration Levels Plan. With the pause and increased levels, the Department estimates that the backlog in parent and grandparent sponsorship applications will be significantly reduced when the program reopens to new applications.[22] The last component of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification is a new 10‑year multiple-entry “Parent and Grandparent Super Visa,” which would allow its holders to stay in Canada for a period of 24 months, rather than the usual 6 months for temporary resident visas. According to information from the Department, this new visa will be available as of December 1, 2011. Applicants will have to: provide a written commitment of financial support from their relative in Canada, who must meet a minimum income threshold; prove they have bought private medical insurance; and complete an Immigration Medical Examination. C. Caps on Privately Sponsored RefugeesMinister Kenney also told the Committee that caps have been introduced on refugee resettlement applications from private sponsors to address the backlog in this category. This change could be accomplished through negotiation with sponsorship agreement holders and did not require the use of Ministerial Instructions. Recommendation 1 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada review its immigration policies to better align the number of applications it accepts for processing with the number of admissions in each year. Recommendation 2 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada review the fees charged for all of its immigration services and programs to discover what, if any, gap exists between what is being charged and actual costs. 1. Federal Skilled Worker ProgramWitnesses were generally supportive of the Government’s action to reverse the legal obligation to process all new applications and curtail the intake of Federal Skilled Worker applications to better align with the Immigration Levels Plan. They called the 2008 legislative amendment that introduced Ministerial Instructions “politically courageous”, “a great leap forward,” and “a bold step”. However, some suggested that alternative methods of limiting Federal Skilled Worker intake would be preferable to the Government’s approach of permitting 500 applications without arranged employment from each listed occupation. One witness suggested instead a two-stage approach, where the Government could select from a pool of applicants that met initial eligibility criteria.[23] Another suggested that charging higher processing fees could be a means to slow intake.[24] Finally, another witness suggested that the Government adjust the pass mark required for Federal Skilled Workers, the mechanism provided in IRPA for regulating intake.[25] Others suggested that the Government amend the points system to favour young immigrants proficient in English or French to both slow intake and improve labour market outcomes for immigrants[26]. The Action Plan for Faster Immigration and Ministerial Instructions streamlined Federal Skilled Worker intake. There remains, however, a backlog of Federal Skilled Worker applications that formed prior to February 2008, which numbered 314,000 as of July 2011. There is a second backlog of Federal Skilled Worker applications received under the first Ministerial Instructions of November 2008, estimated to comprise an additional 140,000 persons. These applications are slowly being drawn from to meet annual Federal Skilled Worker targets. A couple of suggestions were made to address these existing backlogs — one witness proposed adding more processing resources[27], while another suggested that people in the backlog should be able to apply for a work permit and work in Canada while the processing on their permanent resident applications is concluded[28]. The Committee heard that applications received under MI-2 (cap of 20,000 without arranged employment) and MI-3 (cap of 10,000 without arranged employment) were placed directly into processing.[29] The remainder of the Federal Skilled Worker target is met through backlogged applications received under MI-1 and backlogged applications from pre-February 2008, the cut-off date for the first Ministerial Instructions. Witnesses from an organization informed the Committee of the disappointment of applicants under Ministerial Instructions 1 who expected, based on publicity surrounding these Ministerial Instructions, to receive a final decision within a year.[30] These witnesses told the Committee that the expedited processing was only a reality for 4.7% of their clients applying under Ministerial Instructions 1. Further, they reported that applicants with occupations in demand who applied under Ministerial Instructions 1 felt it was somewhat unfair that they should wait in a backlog while those with similar occupations who applied later, under Ministerial Instructions 2 and 3, are processed first. Numbers provided by two CIC missions brought this issue into clearer focus. The Immigration Program manager from New Delhi reported that his mission has the largest inventory of pre-February 2008 Federal Skilled Worker cases.[31] While the mission reduced this backlog by 15% in 2008-09, it still stands at 119,500 persons and applicants faced processing times of 79 months in 2010. Further, the program manager stated “Due to the large number of new cases submitted under Ministerial Instructions, we processed few old-inventory cases in 2010. At the present time we are devoting all available resources to the quick processing of new cases received under the 2nd and 3rd set of Ministerial Instructions.”[32] Similarly, the immigration program manager at the Manila mission reported that they have been successful at processing the majority of Federal Skilled Worker applications under MI-2, many of those lodged under MI-I, and only a few in the pre-February 2008 inventory.[33] How many Federal Skilled Worker applications from each source — the old backlog, the backlog under Ministerial Instructions 1, and new applications received under recent Ministerial Instructions — should be processed in a given year to meet the target was an issue raised by witnesses. Advice on the appropriate balance between processing old backlogged applications and new applications was varied, with most witnesses recognizing the Government’s legal obligation to process all applications. One witness suggested that this legal obligation was not accompanied by a timeframe for processing and urged that the Government prioritize Federal Skilled Workers currently in demand by the Canadian labour market, such as applications lodged under Ministerial Instructions.[34] Another witness made the opposite argument, suggesting that the Government should restrict new applications under Ministerial Instructions for the short term and process primarily backlog applications. He argued that eliminating the backlog quickly is important because the backlog has negative effects on Canada's reputation, the operation of the immigration system, and the labour market, as well as on immigrants themselves. He referenced research showing that younger immigrants have better labour market outcomes, saying “This implies that if an individual sits in the queue for three, four, or five years, there's a simultaneous deterioration in that person's ability to integrate into the Canadian labour market, and it reduces that person's lifetime earnings profile”.[35] The Committee is sympathetic to those with applications in the backlog, some of whom have been waiting for years to receive a final decision. The oldest and largest backlog, that comprised of pre-February 2008 Federal Skilled Worker applications, has been reduced significantly in just over three years. The Committee is satisfied with this progress and urges the Department to continue processing these files as expeditiously as possible. We commend the Government for reducing the pre MI-1 backlog by 50%. This reduction was made two years ahead of schedule. With regard to backlogs formed under Ministerial Instructions, some witnesses have suggested that the Government of Canada take all the applications received under Ministerial Instructions 1 that are in occupations eligible under MI-2 and MI-3 and process them on a first come, first-served basis. Since the Department learned how to control intake more successfully under MI-2 and MI-3, backlogs under Ministerial Instructions should only pose a temporary problem. Others have stated that we can dissolve the existing backlog by sending applicants a letter informing them that they can withdraw their application, and receive a refund.[36] RECOMMENDATION 3: The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada evaluate the different options to deal with the Federal Skilled Worker backlog put forward by witnesses. The Government should then proceed to act in a timely manner to implement whichever recommendation(s) are determined to be the most effective at reducing the backlog in the Federal Skilled Worker program. 2. Federal Investor Immigrant programSome witnesses commented on the use of Ministerial Instructions to adjust the flow of investor immigrant applications. One suggested that the cap introduced under MI-3 “cured” the inventory problem in this category.[37] Another had a less positive view, saying: Recent experience with the federal cap of 700 applications in the investor category would seem to indicate that reducing supply by itself is not a useful tool for curtailing demand. As we know, all 700 applications were filled in one day, due to the operations of a few immigration agencies from one source country. More innovative methods and policies than simple caps are needed to balance demand and supply in critical immigration programs.[38] Responding to this observation on how the investor immigrant cap was filled by immigrants from only one source country, one witness suggested that the Government consider regional caps to ensure a geographical balance.[39] With respect to the current backlog of investor class immigrants, one witness suggested that a component is comprised of people who have submitted multiple applications — under the federal, Quebec, and certain provincial nominee programs. He suggested that the cap on the federal program may have displaced potential applicants into the provincial level programs. As a way to encourage only serious applications to be submitted under the federal investment program, he proposed that the Government require applicants to open a Canadian bank account and deposit 5% of the required investment funds.[40] According to this witness, the rigour of screening undertaken by banks may dissuade non-serious applicants and the Government could benefit from this third‑party assessment of the source of funds. RECOMMENDATION 4 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada complete a thorough review of the program in order to determine what the proper financial requirements should be and any other steps that should be taken to ensure maximum benefit from this program to both the applicant and the Government. 3. Family ClassWhile some witnesses felt that progress was being made to address economic class backlogs, some felt that the backlog of parent and grandparent applications was an outstanding problem requiring Government action. There was some discussion of the potential costs to Canadians of admitting more parents and grandparents, and whether more could be done, such as requiring a bond, to ensure that family sponsors bear the costs.[41] However, one witness suggested that Canada has a “legal as well as a moral obligation” to admit these applicants and that the Government should respond “by biting the bullet and letting the parents and grandparents in, at the cost that will accrue to us in health care and other things”.[42] Others pointed out that parents and grandparents often facilitate the labour market participation of their children by providing child care and they offer a sense of stability in families and cultural communities.[43] They suggested that the long wait time for sponsoring parents and grandparents has led people to make choices with negative impacts for families and for Canada. For example, one witness talked about the “satellite baby” phenomenon, when immigrant parents send their young children back to the country of origin to be raised by parents/grandparents whose applications for sponsorship are stuck in the queue.[44] Another suggested that, faced with the long wait for parent sponsorship, some permanent residents have returned to their country of origin in order to fulfil family responsibilities.[45] Several witnesses raised the issue of uneven backlogs and processing times for family class applications around the world.[46] While CIC officials explained that these differences in processing times arise because of different local realities and risk factors[47], witnesses felt that more could be done to target visa missions with large backlogs and even out waiting times.[48] The Committee agrees that processing times for family class applications are not consistent around the world and that the Department, based on their modernization agenda, should continue to test and implement changes, such as Skype and increased centralized processing in Canada, to speed up processing. Witnesses addressed possible policy options to clear up the current backlog of parent and grandparent applications and prevent future backlogs from growing. One proposal would have parents and grandparents awaiting permanent residence be offered a 10-year multiple-entry visa (with medical expenses covered by family members upfront) to allow them long-term visits rather than immigration. Witnesses were unanimous in their support for this idea, saying that permanent immigration is not necessarily what these prospective immigrants want. In the words of one witness: At present there's a huge backlog of parents and grandparents trying to come to Canada. Indeed, if they only want to come to Canada to be with their family and not to take advantage of our generous social programs, then all we need to do is to give them an extended visa. They will pay for their own transportation, their own health insurance, their own living expenses. That way we solve the backlog problem and they get to be united with their family.[49] Another witness claimed that “for many the only way they can enter Canada is through the sponsorship process”.[50] She further stated that “the multiple-entry visitor visa will open up opportunities for many more people and that will definitely cut down on the backlog.” However, some caution was expressed around the effectiveness of the regular multiple-entry temporary resident visa, which CIC has made available for some time. A witness reported that it was perceived as an attractive alternative, but underutilized.[51] Another witness stated, “We have had the five-year multiple-entry visa in place for a number of years and it has yet to make an impact on our immigration backlog.”[52] Due to the timing of the announcement, few witnesses had the opportunity to speak directly to the super visa for parents and grandparents that the Minister announced. However, given the overwhelming support among witnesses for the concept of a long-term multiple-entry visa for parents and grandparents, the Committee is confident this policy direction will be well received. Given that the super visa presents a new opportunity for families to reunite while at the same time possibly reducing the backlog in parent and grandparent permanent resident applications, the Committee wants to ensure that this new “win-win” measure is publicized as widely as possible. RECOMMENDATION 5 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada promote the new parent and grandparent super visa widely to ensure maximum utilization. RECOMMENDATION 6 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada ensures the parent and grandparent super visa becomes a permanent government policy. The Committee is also eager to ensure that the promise of the new super visa for parents and grandparents is realized and hopes that these visas are issued in a timely and appropriate manner. Minister Kenney told the Committee that CIC is confident the approval rate for super visas will be very high.[53] The Committee was also assured that “the issue of wanting to immigrate will not be a detraction for being considered for a super visa”.[54] From the Committee’s perspective, take up and approval rates are two potential indicators of success. The Committee urges the Department to carefully monitor applications for the super visa, including the relationship between super visa applications and sponsorship applications in the backlog, and track the number and location of super visas issued. RECOMMENDATION 7 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada monitor take up of the super visa over 2012-2013 and evaluate the impact it has had on backlogs as an alternate means for parents and grandparents to be reunited with family. Another policy option recommended by some witnesses to address the existing backlog of parent and grandparent applications was to increase the target for this group within the Immigration Levels Plan, at least on a temporary basis.[55] Parent and grandparent sponsorship accounted for 5% to 6.6% of total immigration in the 2011 Immigration Levels Plan. With respect to how a future backlog of parent and grandparent applications could be prevented, witnesses had a range of ideas on how to limit intake in this category. One proposed that the Government impose an annual cap of 20,000 new parent and grandparent applications.[56] Others proposed that program eligibility be restricted, by reinstating a minimum age for sponsored parents and grandparents,[57] or by using Australia’s approach, which permits parental sponsorship only if the “balance of family” is resident in Australia[58]. One witness suggested that the parent and grandparent category of family class sponsorship be eliminated altogether.[59] However, one witness urged the Government to “carefully examine” policy options such as a cap, underscoring that family reunification is very important, especially to Asian cultures.[60] Others claimed that family reunification is a traditional value in Canadian immigration policy and part of Canada’s competitive advantage in attracting skilled workers.[61] Another witness countered that Canada would continue to be a popular destination even if the Government were to change this program, but there are other benefits, such as a more diverse society, derived from this aspect of Canada’s program.[62] The Committee’s view is that changes to the parent and grandparent sponsorship program, while necessary, should be undertaken very carefully. We fully support the national consultation that the Minister has announced for this purpose and we encourage the Minister to table the ensuing report with this Committee for our consideration. In our view, it is important that sponsors demonstrate they have the ongoing ability to support family members. Accordingly, we recommend the following with respect to the future of the program for parent and grandparent sponsorship: RECOMMENDATION 8 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada ensures its consultations on the future of the parent and grandparent sponsorship program are thorough and include a wide variety of stakeholders and that the final consultations report be provided to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration. RECOMMENDATION 9 The Committee recommends that the consultations include a review of what the appropriate admissions level should be in the parents and grandparents program, including the exploration of a firm cap. RECOMMENDATION 10 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada study the “balance of family” test used by the Australian government. The “balance of family” test allows sponsorship to occur if the greater balance of family of the parent or grandparent resides here in Canada as permanent residents or Canadian citizens. Canada’s position in attracting immigrants is not to be taken for granted. The Committee believes we need a modern immigration system; one that is responsive to the needs of Canadian families and employers, and to prospective immigrants themselves, and is an overall benefit to Canada. The reforms introduced under the Action Plan for Faster Immigration made significant strides toward a modernized and efficient system, marking a turning point in immigration application backlogs and progress toward backlog reduction. As with any new initiative, improvements are possible. In particular, the interaction of Ministerial Instructions requires some fine tuning, so that the perception of fairness prevails. To this end, the Committee recommends that the Government continue to look for ways to improve the implementation of Ministerial Instructions in the skilled worker category. The Committee is optimistic that some of the lessons of successful backlog reduction can also be applied to the parent and grandparent sponsorship program. We believe the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification is an initiative with real potential to ease the backlog in the short and long term. In order to help families reunite in the short term, we urge CIC to promote the super visa for parents and grandparents and to monitor its success as a new initiative. As another short-term measure, the Committee encourages the Government to consider maintaining the 2012 immigration levels based on analysis of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification. Looking to the long term and a redesigned parent and grandparent sponsorship program, it is the Committee’s view that Australia’s “balance of family test” warrants further consideration. We also look forward to the views of Canadians on this question. Immigration application backlogs impede the realization of Canada’s immigration goals and affect all stakeholders. Pressure will continue to mount on the popular or growing streams of Canadian immigration. Hopefully the experience of addressing the Federal Skilled Worker and parent and grandparent backlogs will position the Department to better address backlogs of the future. The Committee has heard numerous testimonies on how managing the intake was successful with the Federal Skilled Workers program; the Government should consider using this approach for other streams that are experiencing large backlogs. [1] Hon. Jason Kenny, Minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 4, October 20, 2011, 1135. [2] Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, Section. 3. [3] Mr. Les Linklater, Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic and Program Policy, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 10, 17 November, 2011, 1115. (Linklater, November 17). [4] Mr. Les Linklater, Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic and Program Policy, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 3, 18 October, 2011, 1125. (Linklater October 18). [5] Canada Gazette Part II, EXTRA Vol. 136, No. 9, June 14, 2002, p. 217, http://gazette.gc.ca/archives/p2/2002/2002-06-14-x/pdf/g2-136x9.pdf. [6] Mr. Marc Audet, Vice-President, Immigrant Investor Program, Desjardins Trust, written submission, p. 3. [7] Mr. Roger Bhatti, Immigration Lawyer, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1130. (Bhatti). [8] Mr. James Bissett, As an Individual, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 4, October 20, 2011, 1245. (Bissett). [9] Citizenship and Immigration Canada, 2011 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, p. 17. [10] These are the main categories within the family class. A small number of “others” are also sponsored through the family class, which may include orphaned minor relatives or a more distant relative of a sponsor without Canadian relatives. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, S. 117(1). [11] Please note that, in fulfillment of international legal obligations, Canada also provides protection to people who arrive here and make a refugee claim. When you add refugees landed in Canada and their dependents, the total “protected persons” category comprises an average of 11% of total immigration over the last decade. [12] Linklater, October 18, 1115. [13] Linklater, October 18, 1120. [14] Linklater, October 18, 1250. [15] Mr. Arthur Sweetman, Professor, Department of Economics, McMaster University, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1220. (Sweetman). [16] The Hon. Diane Finley, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Committee Evidence, 39th Parliament, 2nd Session, Meeting No. 45, May 13, 2008, 1535. [17] Linklater, October 18, 1115. [18]. Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Operational Bulletin 252 — December 2, 2010, Regulatory and Administrative Changes to the Federal Immigrant Investor Program. [19] Citizenship and Immigration Canada, CIC’s Response to a Request for Information Made by the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration on October 18, 2011, December 14, 2011. [20] Linklater, November 17, 1115. [21] Citizenship and Immigration Canada, “Backgrounder — Phase 1 of the Action Plan for Faster Family Reunification,” http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/backgrounders/2011/2011-11-04.asp. [22] Ms. Claudette Deschênes, Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 10, November 17, 2011, 1130. [23] Mr. Patrick Grady, Economist, Global Economics Ltd., Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 5, October 25, 2011, 1150. (Grady). [24] Mr. Warren Creates, Immigration Lawyer, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 6, October 27, 2011, 1205. [25] Sweetman, 1220. [26] Mr. Naeem (Nick) Noorani, President, Destination Canada Information Inc., Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 9, November 15, 2011, 1205; Mr. Colin Busby, Senior Policy Analyst, C.D. Howe Institute, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 9, November 15, 2011, 1220. [27] Mr. Michael Atkinson, President, Canadian Construction Association, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 6, October 27, 2011, 1220. [28] Ms. Katrina Parker, Lawyer, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 6, October 27, 2011, 1235. (Parker). [29] Ms. Claudette Deschênes, Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 3, October 18, 2011, 1210. [30] Parker; Mr. Ali Mokhtari, CanPars Immigration Services Inc., Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1215. [31] Mr. Sidney Frank, Immigration Program Manager, New Delhi, India, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 9, November 15, 2011, 1115. [32] Ibid. [33] Mr. Kent Francis, Immigration Program Manager, Manila, Philippines, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 9, November 15, 2011, 1120. [34] Mr. Martin Collacott, Spokesperson, Centre for Immigration Policy Reform, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1120. (Collacott). [35] Sweetman, 1220. [36] Collacott, 1140. [37] Mr. Richard Kurland, Policy Analyst and Attorney, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 4, October 20, 2011, 1235. (Kirkland). [38] Mr. Nigel Thomson, Member, Board of Directors, Canadian Migration Institute, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 8, November 3, 2011, 1130. (Thomson). [39] Mr. Daniel Perron, Director and Business Head, Global Investor Immigration Services, HSBC Trust Company, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 8, November 3, 2011, 1230. (Perron). [40] Perron, 1225. [41] Mr. Herbert Grubel, Senior Fellow, Fraser Institute, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 5, October 25, 2011, 1115. [42] Bissett, 1245. [43] Ms. Amy Casipullai, Senior Policy and Communications Coordinator, Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants (OCASI), Committee Evidence, Meeting no. 5, October 25, 2011, 1300. (Casipullai). [44] Mr. Tomas Tam, Chief Executive Officer, SUCCESS, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 5, October 25, 2011, 1220. (Tam). [45] Mr. Felix Zhang, Coordinator, Sponsor our Parents, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1225. (Zhang). [46] Bhatti, 1130; Mr. Dan Bohbot, President, Quebec Immigration Lawyers Association (AQAADI), Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 7, November 1, 2011, 1210. [47] Ms. Claudette Deschênes, Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 11, November 24, 2011,1205. [48] Zhang, 1125; Tam, 1220. [49] Mr. Tom Pang, President, Chinese Canadian Community Alliance, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 5, October 25, 2011, 1210. [50] Casipullai, 1245. [51] Bhatti, 1145. [52] Mrs. Sima Sahar Zerehi, Communications Coordinator, Immigration Network, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 9, November 15, 2011, 1220. [53] Hon. Jason Kenney, Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 11, November 24, 2011, 1150. [54] Ms. Claudette Deschênes, Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations, Department of Citizenship and Immigration, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 11, November 24, 2011,1150. [55] Kurland, 1300 and Casipullai, 1220. [56] Kurland, 1310. [57] Bisset, 1245. [58] Collacott, 1145. [59] Mr. Joseph Ben-Ami, President, Canadian Centre for Policy Studies, Committee Evidence, Meeting No. 5, October 25, 2011, 1115. [60] Tam, 1220. [61] Casipullai, 1220 and Zhang, 1225. [62] Sweetman, 1240. |