The Committee’s witnesses held a variety of

views about the “health” of the nation’s current retirement income system, the

extent to which reforms are needed to public pensions, voluntary tax-assisted

retirement savings vehicles and/or occupational pension plans, and Canada’s

international ranking in respect of pension adequacy.

Various elements of Canada’s retirement

income system have been reformed over time, but in Canada, like in a number of

other countries, the recent global financial and economic crisis highlighted

the need to reform some elements of the system. In Canada, federal and

provincial governments, as well as other stakeholders, have been examining

whether—and, if so, what—reforms are needed to ensure a standard of living in

retirement that is at least adequate.

The views of the Committee’s witnesses about

the need for reform varied, with some arguing that the country’s retirement income system is basically sound, although limited reforms may be required in

specific areas. For example, Ms. Shirley-Ann George and Ms. Sue Reibel, of the

Canadian Chamber of Commerce, suggested that reform efforts should be focused

on improvements to key areas rather than on fundamental changes, a view that

was supported by Carleton University’s Mr. Ian Lee, who—appearing on his own

behalf—said that there is no pension crisis, and by BMO Financial Group’s Ms. Tina Di Vito.

This opinion was also expressed by Mercer’s Mr. Malcolm Hamilton, who

appeared on his own behalf and described the current situation as an economic

and financial markets—rather than a pension—crisis. He said that he could not

think of a country that has fewer problems than Canada in respect of retirement

saving.

Other witnesses, however, believed that

broader reforms are needed. Open Access Limited said that there is widespread

acknowledgement that change is required. Ms. Susan Eng, of the Canadian

Association of Retired Persons, noted a C.D. Howe Institute report by Mr. Keith

Ambachtsheer, entitled The Canada Supplementary Pension Plan (CSPP), which

argued that Canadians have inadequate retirement saving. Specifically, she

observed that nearly 30% of Canadian families have not saved for retirement and

that the registered retirement savings plan (RRSP) system is not fully

utilized. Ms. Eng also highlighted inequities between private- and

public-sector pension plans, a point that was also made by Mr. James Pierlot, a

pension lawyer who appeared on his own behalf.

Similarly, Mr. Scott Perkin, of the Association

of Canadian Pension Management, indicated that the lack of occupational pension

plans is one of the main impediments to adequate retirement income. On that

subject, Mr. Dean Connor, of the Canadian Life and Health Insurance

Association, explained that the administrative costs and complexities of such

plans stop many employers, especially small firms, from establishing them.

Mr. Perkin also commented that insufficient

voluntary retirement saving is another impediment to adequate retirement income.

He argued that individuals are not saving enough on their own, partly due to

the complexity of the current savings mechanisms. The Rotman International

Centre for Pension Management’s Mr. Keith Ambachtsheer, who appeared on his own

behalf, also spoke about this issue, saying that the average Canadian does not

know how much to save in order to ensure adequate income once retired.

Furthermore, he noted that administrative costs on mutual funds, which

constitute a sizeable proportion of retirement saving, are often 2% or higher,

making it difficult to reach a reasonable income replacement rate.

Additionally, Ms. Diane Urquhart, an

independent financial analyst appearing on her own behalf, argued that Canada

provides relatively less protection for occupational pension plan members in

the event of their employer’s bankruptcy. This view was also held by witnesses

from Nortel Retirees’ and Former Employees’ Protection Committee. However, Mr.

Hamilton brought a Mercer publication, Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index,

to the Committee’s attention. According to this report, in 2009, Canada was

tied for second among 11 countries, behind the United Kingdom, on the issue of

employee protection in a fraud, mismanagement or insolvency situation, including

the protection of accrued benefits in the case of employer insolvency.

Furthermore, the report highlighted that—among the 11 countries—Canada,

Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States were the only jurisdictions

that offered some sort of protection for accrued benefits in the event of

insolvency in 2009.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD)’s Mr. Edward Whitehouse, who appeared on his own

behalf, provided an international context for the examination of Canada’s

retirement income system, comparing it to 12 other OECD member countries.

He concluded that, for several reasons, Canada has a relatively

“high-performing” retirement income system. For example, poverty among Canadian

seniors is relatively low, with a poverty rate of 4.4% in the mid-2000s

compared to the OECD average of 13.3%. He argued that the relatively low

poverty rate is partly due to Old Age Security (OAS) and Guaranteed Income

Supplement (GIS) benefits, which provide an effective and universal safety net

for Canadian retirees. However, while recognizing that Canada has a retirement

income system that is very efficient at reducing poverty in old age, the

University of Saskatchewan’s Mr. Daniel Béland, who appeared on his own behalf,

argued that the role played by pensions in replacing income should go beyond

replacement at the poverty line. In his view, the Canadian retirement income

system does not adequately fulfill this role.

Supporting this view, Mr. Jean-Pierre

Laporte, a pension lawyer who appeared on his own behalf, noted that—in 2006—Canada

ranked 12th out of 14 OECD member countries in terms of the nation’s

pension income replacement rate, at 57.9% of pre-retirement income. However,

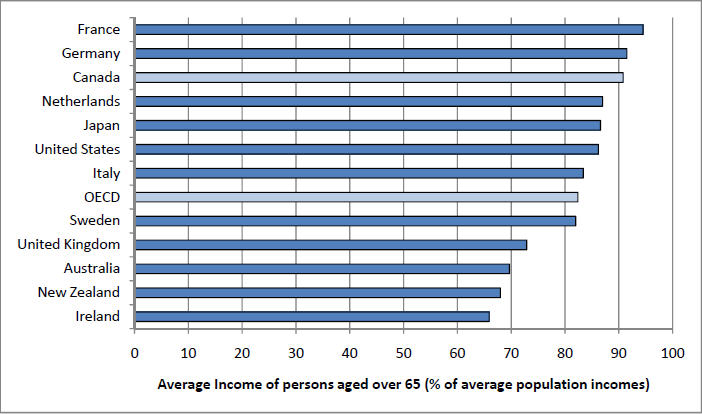

the OECD report presented by Mr. Whitehouse noted that, on average and in the

mid-2000s, Canadians over age 65 had incomes equal to 91% of the average

Canadian population, giving Canada a ranking of 3rd among 12 OECD

member countries.

Figure 1: Average Income of Persons Aged More than 65 Years as a Proportion of

the Average Income of the Population, Various Countries, Mid-2000s

Source: Whitehouse, Edward. “Canada’s Retirement Income

Provision: An International Perspective,” report presented by Mr. Whitehouse to

the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance, 27 May 2010.

The long-term financial sustainability of

Canada’s retirement income system was also noted by Mr. Whitehouse. He observed

that, while the population will age and public expenditures on pensions will

rise, the current system’s public expenditures—which are equivalent to 4.5 % of

gross domestic product (GDP)—are well below the OECD average of 7.4%. Moreover,

by 2060, public spending on pensions in Canada is projected to increase to 6.2%,

still below the current OECD average. Mr. Whitehouse also noted that the

combination of public and private sources of retirement income in Canada’s

system provides protection against the risk and uncertainties affecting it.

Finally, he asserted that another favourable attribute of the pension system in

Canada is that it does not provide incentives for early retirement.

While Mr. Whitehouse identified positive

aspects of Canada’s retirement income system, he indicated that there is room

for improvement in respect of occupational pension plans, private retirement

saving and public pensions. More specifically, he suggested that private

pension plan coverage could increase, particularly for low- and middle-income

earners. Regarding such plans, he commented that automatic enrolment is

occurring in some countries, and that other countries are introducing and

streamlining tax incentives, particularly for low-income earners.

As well, Mr. Whitehouse noted that

contributions to registered retirement savings plans are small in comparison to

occupational pension plans, and stressed that the administrative charges for

the former are relatively high; he argued that such costs should be reduced.

Finally, although Canada’s pension system does not provide incentives to leave

the workplace early, he provided figures indicating that the participation rate

of older Canadians nearing the retirement age of 65 is somewhat low compared to

other OECD countries.

Regarding public pensions, Mr. Whitehouse

suggested increasing the pension age, and indexing OAS and GIS benefits to

growth in average earnings to ensure that retirees’ standard of living does not

decline relative to the average population. Finally, to provide better

protection against risk, he suggested that the investments in defined contributions

pension plans of people near retirement should be automatically shifted to less

risky assets.

Finally, Mr. Hamilton spoke to the Committee

about Mercer’s Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index report, which

evaluates the state of the retirement income system in Canada and ten other

countries in three broad areas: adequacy of benefits; long-term sustainability

of the system; and the integrity of the private-sector system, with a focus on prudential

regulation, governance, risk protection and communication. This report was also

mentioned by Mr. Connor. Overall, Canada ranked 4th out of the

eleven countries in 2009, behind the Netherlands, Australia and Sweden.

According to the report, the Canadian retirement income system could be

improved by addressing the low coverage of occupational pension plans and the

low household savings rate. It was also argued that Canada should index the

pension age to life expectancy and ensure that voluntary retirement saving is

used for retirement purposes and not withdrawn earlier for other expenditures.