RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

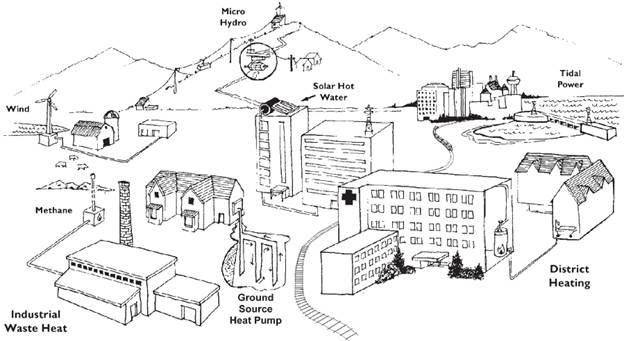

CHAPTER 1—OVERVIEW Energy is traditionally distributed to individual buildings and facilities with little choice over energy sources, and varying energy consumption practices. Substantial inefficiencies can result from this approach, with no use of economies of scale or energy reuse between organizations. Individual leading-edge technologies and practices yield limited impacts by not being integrated.[7] Figure 1: Possible features of an integrated energy system

Source: Green Municipalities—A Guide to Green Infrastructure for Canadian Municipalities prepared for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) by the Sheltair Group, May 2001[8]. An integrated energy system assimilates energy supply and consumption decisions across different community needs (such as heating, cooling, lighting and transport) and sectors (such as land-use, transportation, water, waste management, and industry), by supporting mixed-use development[9], local renewable energy sources, and smart district energy grids for efficient energy management.[10] A few communities in Canada are already applying an integrated approach to energy planning, including energy supply and demand. However, according to Carol Buckley, Director General of the Office of Energy Efficiency, these communities are “fairly rare [because they are attempting] exactly the opposite of the status quo in the way energy [...] is designed and [...] used...”[11] By performing bulk purchases and installations at the community level, integrated energy planning has the capacity to support efficiency in land-use and transportation planning, water and waste management, construction, and energy use practices and technologies within buildings.[12] Integrated energy systems also support effective resource management by maximizing energy efficiency and synergy through closed-loop designs (where waste from one area is fuel to another), and by encouraging investment in diverse and flexible energy solutions (including renewable sources), in adaptation to fluctuating energy prices and an uncertain and changing future. The end result would achieve reductions in energy demands/costs and greenhouse gas emissions, gains in local employment and economic development opportunities, and an overall improved and more sustainable quality of life.[13] The application of integrated energy approaches is challenging due to the large number of individuals and organizations required to carry out integrated community projects, and the underpublicized benefits of such projects. Implementation is often obstructed by the high initial cost of some necessary technologies and infrastructures, and the lack of support from existing regulatory frameworks. For example, according to Carol Buckley, “many planning regulations support low-density development and [...] penalize redevelopment in the core of cities,” and in some jurisdictions, local utilities are denied partnership in energy production facilities, which limits their participation and potential financial contribution.[14] There are numerous short-term benefits and “quick wins” to integrated energy systems, such as immediate energy savings and greenhouse gas reductions. However, other benefits are rather long-term, and their progress is difficult to evaluate due to the lack of standardized measurements and the multiplicity of the mixed uses that require monitoring. Privacy issues emerge where larger blocks of data, at the community level, are required. For example, inquirers often lack access to utility information. The reliability of measurements advances with experience (e.g. through existing and pilot projects), which is still lacking in the area of integrated energy systems.[15] Jurisdiction and Responsibilities In his discussion of district energy systems, Douglas Stout, Vice-president of Marketing and Business Development at Terasen Gas, outlined two categories of “players”:[16]

The Constitutional Act, 1867 divides the power to make law between “the federal Parliament and the provincial legislatures.” While the Act assigns specific powers to the federal and provincial governments, as shown in table 1, environmental issues involve many areas under different jurisdictions, making the environment an area of shared jurisdiction. Municipalities, strictly speaking, “draw their powers to pass bylaws on environmental matters from the provincial municipal acts that create them and specify their powers to legislate.” However, the Supreme Court of Canada has recently adopted a “purposive interpretive approach, analogous to that used for constitutional interpretation… to ensure that municipalities can deal effectively with emergent environmental problems…” As a result of the Court’s purposive approach to interpretation, “in addition to municipalities potentially exceeding their powers under provincial municipal acts, their bylaws may also be outside provincial legislative powers under the Constitution Act, 1867,” and still be valid.[17] Table 1: Divisions of power between the federal government and the provinces under the Constitution Act, 1867

Source: Paul Muldoon et al., 2009, p. 21. Integrated energy planning therefore lies within provincial, territorial and municipal jurisdiction, with particular requirement for provincial engagement given provincial constitutional powers. Federal participation entails contributions through the government’s research and funding capacity, experience in establishing national visions and programs (e.g. in energy efficiency, renewable energy, carbon pricing, etc.), and the ability to bring organizations together.[18], [19] Municipal (and sometimes regional) expertise is most qualified for setting targets and strategies to address the diverse planning situations across Canada. This emphasizes a bottom-up approach to decision making with respect to community integrated energy planning.[20] Municipalities are involved directly, by establishing energy services (e.g. district energy corporations, poles, wires), and indirectly, by promoting certain forms of development (e.g. high-density, transportation-oriented, etc.). Planners, builders and site-designers assemble the built environment that shapes a community’s energy-use patterns.[21] [7] Carol Buckley, Office of Energy Efficiency, Department of Natural Resources, Committee Evidence, February 26, 2009. [8] QUEST, Integrated Energy Systems in Canadian Communities: A Consensus for Urgent Action, March 2008, document submitted to the Committee. [9] Mixed-use development allows for multiple uses within a building or a planning zone. In the context of integrated energy planning, it refers to communities with a combination of land-uses, including commercial, industrial, institutional, and a range of residential land-uses. [10] QUEST, Collaborating to Promote Integrated Community Energy Systems, presentation submitted to the Committee, February 26, 2009. [11] Carol Buckley, Office of Energy Efficiency, Department of Natural Resources, Committee Evidence, February 26, 2009. [12] Ibid. [13] QUEST, Integrated Energy Systems in Canadian Communities: A Consensus for Urgent Action, March 2008, document submitted to the Committee. [14] Carol Buckley, Office of Energy Efficiency, Department of Natural Resources, Committee Evidence, February 26, 2009. [15] Kevin Lee, Housing Division, Office of Energy Efficiency, Department of Natural Resources, Committee Evidence, February 26, 2009. [16] Douglas Stout, Marketing and Business Development, Terasen Gas, Committee Evidence, March 5, 2009. [17] Paul Muldoon et al. (2009), An Introduction to Environmental Law and Policy in Canada, p. 20-23, Emond Montgomery Publications Limited, Toronto. [18] Carol Buckley, Office of Energy Efficiency, Department of Natural Resources, Committee Evidence, February 26, 2009. [19] Mel Ydreos, Operations, Union Gas Limited, Committee Evidence, March 5, 2009. [20] Douglas Stout, Marketing and Business Development, Terasen Gas, Committee Evidence, March 5, 2009. [21] Canadian Urban Institute, Integrated Energy Planning: A Role for Planners and Communities, document submitted to the Committee, March 26, 2009 |

||||||