FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

This chapter elaborates on the effects of the EI program on women. It recommends improvements and reforms to be made to the EI program that address the main issues raised by the witnesses. Based on the testimony that we heard, the Committee is aware that the EI program can impact women both positively and negatively. The EI program’s special benefits provide women and men with the opportunity to stay at home to care for their newborn or to care for a dying relative. However, witnesses have testified that the EI program inadvertently discriminates against women because it is designed to provide income support for the full-time, permanent worker. According to one witness, “[o]ne has to be very careful to avoid implicit gender biases in the parameters of the program.[65] The key thing that has changed is that over the years the employment insurance system in Canada has been increasingly restricted to what we could call the standard employment model. It presupposes that everybody who works for money works in standard employment—a full-time permanent job with full benefits, 12 months a year, going on forever into the future or until something better comes along.[66] The majority of the witnesses recommended that the EI program be improved and reformed so as to respond to women’s labour market realities and their caregiving and family responsibilities. Other witnesses indicated that the EI program should not be changed and that other solutions be sought in order to address barriers women face in accessing EI. For example, Dr. Schirle pointed out that policies that improve women’s access to full-time permanent jobs such as employment equity programs and pay equity program are a more appropriate policy action to address women’s precarious employment conditions.[67] In addition, Dr. Schirle warned the Committee that modifying EI program rules to accommodate the needs of women in precarious employment may “create an incentive for men and women to take on less secure employment and develop a long-term dependency on the EI program.” She also noted that it may make the program more expensive.[68] Because of the overwhelming demand for EI program reform that was voiced by witnesses, the Committee proposes several improvements to the EI program. I. The Effects of the Current EI System on Women With the enactment of the Employment Insurance Act in 1996, eligibility requirements were changed from a weeks-based system to an hours-based system. Witnesses repeatedly pointed to the negative effects that this switch had on part-time workers, particularly on women who predominate in this form of employment. Mr. Neil Cohen, Executive Director, Community Unemployed Help Centre[69], and Ms. White[70] quoted the Umpire’s ruling in the Kelly Lesiuk case in order to demonstrate the discriminatory impact that the hours-based system has on part-time workers: In my view, the eligibility requirements demean the essential human dignity of women who predominate in the part-time labour force because they must work for longer periods than full-time workers in order to demonstrate their workforce attachment…. Since women continue to spend approximately twice as much time doing unpaid work than men, women are predominantly affected. Thus, the underlying message is that, to enjoy equal benefit of the law, women must become more like men by increasing their hours of paid work, notwithstanding their unpaid responsibilities. [71] [HON. R. E. SALHANY, Q.C., UMPIRE] Many immigrant and refugee women are employed in part-time work and cannot meet the minimum qualification requirements under the hours-based system. Ms. Spencer noted the following: It is deeply troubling that the majority of immigrant women who pay into the EI fund cannot access benefits. Neither can they access training opportunities that are tied to EI eligibility.[72] The Committee is aware that Budget 2009 invests $500 million over two years in a Strategic Training and Transition Fund to support individuals who do not qualify for EI training, such as the self-employed or those who have not been in the labour force for a prolonged period of time. A. Effect on the Part-Time Worker versus the Full-Time Worker Dr. Rose-Lizée illustrated how the EI system does not address the needs of women who work part-time or in precarious employment. She noted that a typical male worker who works 40 hours a week requires 16 weeks to qualify for EI. In contrast, a typical female part-time worker who works 15 hours a week requires 42 weeks to qualify for EI benefits. Figure 14: Example of Number of Insurable Weeks Needed to Qualify for EI Regular Benefits for a Hypothetical Full-Time and Part-Time Employee

Source: Information compiled by Committee analysts based on witness testimony. B. Minimum Qualification Requirements Under the weeks-based system, a worker was required to have a minimum of 12 to 20 weeks of insurable employment to qualify for regular benefits, depending on the regional rate of unemployment. Because the minimum insurability requirement entailed at least 15 hours of work per week, the minimum qualification requirements ranged from 180 to 300 hours, depending on the regional unemployment rate (Please refer to Appendix 3, Required Number of Weeks of Insurable Employment). For example, a part-time worker employed in Toronto would have needed 18 weeks of insurable employment with a minimum of 15 hours of work a week to qualify for insurance benefits. This worker would have been able to qualify for regular benefits with only 270 hours of work. As the example in Figure 14 illustrates, a part-time worker in the service sector who works 29 hours a week for 18 weeks would have accumulated 522 hours of work during the qualifying period. Likewise, a part-time worker in the grocery sector who works 25 hours a week for 18 weeks would have accumulated 450 hours during the qualifying period. Under the weeks-based system, both workers would have qualified for regular benefits, having met the minimum qualification requirement of 270 hours. Figure 15: Weeks-Based System for Minimum Qualification Requirements Hypothetical Example

Source: Information compiled by committee analysts based on witness testimony. Under the hours-based system, workers need a minimum of 420 to 700 hours of insured work to qualify, depending on the regional rate of unemployment. To meet the minimum qualification requirements under the hours-based system, women therefore need to work more hours than under the weeks-based system. Using the same example stated above, Figure 16 shows that the part-time service sector worker and grocery sector worker employed in Toronto now need 630 hours of work to qualify for EI benefits. With the same number of hours worked, the service sector worker needs 22 weeks of insurable earnings and the grocery sector worker needs 25 weeks of insurable earnings to qualify for regular benefits. Figure 16: Hours-Based System for Minimum Qualification Requirements Hypothetical Example

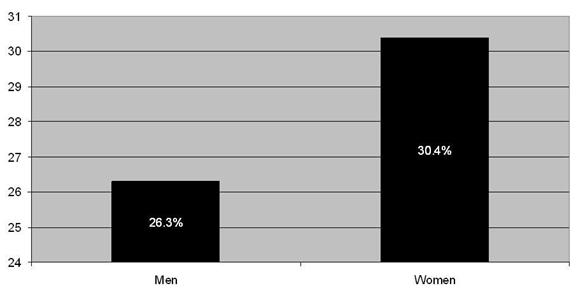

Source: Information compiled by committee analysts based on witness testimony. C. Duration of Benefits and People Who Have Exhaused their Benefits The Committee heard that even though part-time workers are working for a longer period of time, the duration of payable benefits is less under the hours-based system compared to the weeks-based system.[73] The hours-based qualification system has the effect of putting women in a situation where they are more likely to exhaust their EI benefits. The Committee heard from several witnesses, including Ms.Charette, Deputy Minister at HRSDC, that in 2005-2006, 30.4% of women exhausted the benefits they were entitled to receive compared with 26.3% of men (see Figure 16).[74] She noted that the additional five week duration of EI benefits is intended to address the exhaustion of benefits.[75] Figure 17: Percentage of Regular EI Beneficiaries who Exhaust their Benefits, by Sex, 2005/06

Source: Employment Insurance Monitoring Assessment Report, 2005-2006 (Evidence submitted by Dr. Leah Vosko, March 26, 2009). According to the 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, a larger proportion of women than men exhaust their benefits due to the fact that women, on average, are entitled to fewer weeks of benefits (29.9, versus 26.5 for men), since women generally have fewer hours of insurable employment.[76] Dr. Vosko explained to the Committee that even with the additional five weeks of benefits, the duration of benefits is still lower than what was available under the weeks-based system (please refer to Appendix 4, Table of Weeks of Benefit, Unemployment Insurance Act). But if we take the case of a grocery store worker again, a grocery store worker in this region with an average of 25 hours a week and steady work for a full 52 weeks before the layoff—so 1,300 insured hours—is eligible for a maximum of 31 weeks of benefits until September 2010, and after that the duration declines to 26 weeks. This worker would have been eligible for up to 40 weeks under the pre-existing weeks system.[77] In the example shown in Figure 18 and Figure 19, the maximum number of weeks payable for regular benefits is less under the hours-based system even with the extended five weeks of benefits that is in effect until September 2010. This means that given women’s labour market realities, the 2009 benefit entitlement under EI is relatively less than that afforded to women prior to the EI reform of the 1990s. Figure 18: Hours-Based System — Duration of Benefits Hypothetical Example

Source: Information compiled by committee analysts based on witness testimony. Figure 19: Weeks-Based System — Duration of Benefits Hypothetical Example

Source: Information compiled by committee analysts based on witness testimony. The Committee also heard that many women will not benefit from the additional 5-week duration of EI benefits since they do not meet the minimum qualification requirements. Under the hours-based system, many part-time workers were insured for the first time. However, many are unable to qualify for benefits. Dr. Leah Vosko noted that in 2004, 76% of unemployed workers who had previously worked part-time contributed to EI but less than 20% of these contributors received benefits. For full-time workers, 81% contributed to EI but only 55% received benefits.[78] Ms. Carole Vincent informed the Committee that not every hour worked is treated equally under the rules of the EI program. The major reform of 1996 introduced what is called an hour-based system; however, not every hour of work is treated equally under EI. The EI rules, which are quite complex, give rise to major disparities—and some may call them inequities—in the extent to which workers who pay premiums into the program can benefit from it. Workers who have work patterns or work schedules that best fit the EI rules for eligibility and calculation of benefits will benefit more from EI.[79] This is especially apparent when the divisor rule is applied to calculating average weekly earnings. According to Dr. MacDonald and other witnesses, the rule contributes to decreasing a claimant’s average weekly earnings and penalizes those with irregular or fluctuating earnings.[80] (Please refer to Appendix 2, Table of Weeks of Benefits, Employment Insurance Act). The formula, basically, for calculating average earnings should be neutral with regard to the timing of work. It shouldn't be rewarding one work pattern and penalizing another.[81] As Dr. MacDonald pointed out in a recession both full-time and part-time work should be equally protected and “the parameters of the program should not favour the person who was working in a full-time context.”[82] On the issue of whether part-time should be equally protected to full-time, even if somebody chose part-time because they wanted to be home with their children, if that job then disappears in the recession, like a full-time job might disappear or a part-time job might disappear, is there any reason why that part-time person should have less likelihood of qualifying for income replacement?[83] HRSDC has a pilot project in place that calculates EI benefit rates based on the highest 14 weeks of insurable earnings over the last 52 weeks. The project is designed to encourage unemployed workers to accept various forms of employment in regions where unemployment rates are 8% or above.[84] This project may alleviate the inequities that arise between the valuation of part-time and full-time insurable earnings and may result in improved average weekly earnings for the claimant. The 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report stated that “preliminary results indicate that claimants who received higher weekly benefits due to the Best 14 Weeks pilot project were mainly youth, women, part-time workers, low-skilled workers and workers in low-income families.”[85] Another concern raised by witnesses involves the calculation of benefits under the Variable Entrance Requirements (VER). HRSDC informed the Committee that these adjustments to the regional unemployment rate “allow for a certain measure of automatic responsiveness to local job markets.”[86] Some witnesses believed the VER to be inequitable. Mr. Battle explained in his testimony:[87] [A]n unemployed person is an unemployed person, whether they live in a low-unemployment area or a high-unemployment area, as far as I'm concerned. I don't know how you can tell. You know, the premiums aren't based on unemployment regions. We don't have variable premiums that we pay to support it; we all pay the common premium, of course. But what you get at the end of it depends upon where you live.[88] A. Uniform Qualification Requirements The majority of the witnesses recommended that a uniform qualification requirement of 360 hours be put in place for both regular and special benefits. Such a measure addresses the exclusion of part-time workers, predominantly women, from the EI program. It provides them with access to EI benefits by reducing the number of insurable hours needed to qualify. A uniform qualification requirement also addresses the inequities that exist under the Variable Entrance Requirements. Figure 20: Example of Number of Insurable Weeks Needed to Qualify for EI Regular Benefits with a Uniform Requirement of 360 Hours

Source: Information compiled by committee analysts. RECOMMENDATION 5: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada implement a uniform 360-hour qualification requirement, irrespective of regional unemployment rates or the type of benefit. This would establish that Employment Insurance is available to part-time workers. B. Changing Qualification Requirements from Hours to Weeks Even though the Committee endorses an hours-based qualification requirement, the Committee heard from several witnesses that the EI program should be returned to a weeks-based qualification requirement. As discussed above, the hours-based system has had a negative impact on part-time workers both in terms of access and duration of benefits. RECOMMENDATION 6: The Committee recommends that:

C. Extending Benefits Duration As noted in Chapter 1, the federal government has recently introduced a temporary measure to extend regular benefit entitlement from 45 to 50 weeks. Several witnesses recommended that such a measure should become permanent since it would help unemployed workers, particularly those in non-standard work, who are at risk of exhausting their benefits. RECOMMENDATION 7: The Committee recommends that the maximum benefit entitlement for regular benefits be extended to 50 weeks on a permanent basis and that additional weeks of entitlement should be considered by Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. RECOMMENDATION 8: The Committee recommends that:

According to the EI Act[90], all claimants are not entitled to be paid benefits until they have served a two-week waiting period. This applies to all types of EI benefits. The Committee heard that the waiting period should be eliminated for both regular and special benefits. The Committee heard from several witnesses that the two-week waiting period for special benefits claims should be eliminated. For example, Ms. Sue Calhoun, President, Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs, noted the following: Currently, to access EI maternity/parental benefits, you have a two-week waiting period. I'm not sure what that's all about, and I know a lot of people have said the same thing to you: what is that two-week waiting period all about anyway, especially in a situation when you're getting maternity/parental benefits….[91] The Committee is aware that this waiting period is in place as a basic co-insurance feature of the program that is similar to the deductible for other insurance plans.[92] HRSDC has informed us that the waiting period serves an administrative purpose as it allows for the processing and verification of claims, and eliminates very short claims which would be relatively costly to administer.[93] However, given the concerns raised by witnesses, RECOMMENDATION 9: The Committee recommends that the two week waiting period be eliminated for all benefits. E. Maximum Rate of Weekly Benefits The majority of witnesses recommended that the benefit rate should be raised from 55% of average weekly insurable earnings to 60% or more. Ms. Lucille Harper, Executive Director, Antigonish Women's Resource Centre, recommended that the “EI is set at a rate that is no lower than 10% of the low-income cutoff for any given region.”[94] The Committee heard that the current average weekly earnings are insufficient and for some women, places them below the poverty line.[95] RECOMMENDATION 10: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada increase the benefit rate from 55% to 60% or more of average weekly insurable earnings for both regular and special benefits. F. Calculation of Average Weekly Insurable Earnings and Divisor Rule As noted above, several witnesses indicated that they were unhappy with the divisor rule[96] used to calculate average weekly earnings and its effects on women. These witnesses preferred that the divisor rule be removed since it unfairly penalizes women in non-standard employment. As noted earlier, the rule contributes to decreasing a claimant’s average weekly earnings and penalizes those with irregular or fluctuating earnings.[97] Several witnesses recommended that the best 12 weeks within the whole qualifying period be used as the reference period for determining average weekly insurable earnings. At the same time, the Committee is aware that HRSDC has in place a ‘Best 14 Weeks’ pilot project. Preliminary results reveal women were among the claimants who received higher weekly benefits. Therefore, RECOMMENDATION 11: The Committee recommends that the government, based on the preliminary results of the ‘Best 14 Weeks’ pilot project, adopt a new rate of calculation period equal to the qualifying period. Only those weeks with the highest earnings in the new rate calculation period would be included, and these earnings would be an average of the best 14 weeks of insurable employment. The Committee also heard that calculation of benefits for farm owners needs to be based on net rather than gross income. RECOMMENDATION 12: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada examine calculating benefits for farm owners on net income rather than gross income. III. The Effects of New Entrant and Re-entrant Rules (NERE) Witnesses told the Committee that the NERE[98] rules have had a “disproportionately negative effect on new immigrants in large urban centres” [99] as well as on students who are entering the workforce. The ones who stand out in my mind as needing some serious, focused attention are, first of all, new entrants into the workforce. Those workers include both immigrant workers—people who are new to Canada—and people who have just finished their education and are coming out of university with huge debt, if they've been so fortunate to attend. These workers have to establish 910 hours of eligibility before they qualify for establishing the minimum employment insurance benefits. So there is the whole question of the new entrants.[100] HRSDC currently has a pilot project (the New Entrant/Re-entrant project) in place that allows claimants to qualify for regular benefits with a minimum of 840 hours instead of 910 hours. This pilot project began in December 2005 and has been extended to December 2010.[101] According to the 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, preliminary results indicate that the “NERE pilot project primarily benefited youth, people in low-income families and people whose last job was temporary non-seasonal.” [102] However, the Committee heard from several witnesses that the NERE rules should be eliminated. Therefore, RECOMMENDATION 13: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada consider eliminating the New Entrants and Re-entrants rules. IV. Maternity/Parental Benefits Witnesses raised concerns that the special benefits provided under the EI program should not be part of an employment insurance program. Ms. Vincent noted that given women’s increased family and caregiving responsibilities a separate program may be needed.[103] Other witnesses found that a separate program for special benefits may not be an appropriate solution. Referring to the Compassionate Care Benefits, Mr. Neil Cohen pointed out that it is worthwhile to have these types of benefits “entrenched in a program that is a pillar of our social fabric in Canada.”[104] A. Positive Effects of Maternity/Parental Benefits Witnesses highlighted the beneficial effects of the EI program’s maternity/parental benefits. Ms. Charette, Deputy Minister at HRSDC, informed the Committee that the current maternity/parental benefits provide women with the flexibility to stay at home to care for their newborn child. The 50 weeks of EI maternity and parental benefits play a critical role in supporting Canadian families by providing temporary income replacement for parents of newborn or newly adopted children. These benefits provide flexibility for many women and men to stay home to nurture their child during that important first year.[105] The Committee heard from Mrs. Verna Heinrichs, who appeared as an individual, on how women benefit from the EI program’s maternity/parental benefits: I know of teachers, nurses, aestheticians, chefs and others who have benefited from the 15 weeks of employment insurance coverage for maternity leave and the 35 weeks of parental benefits through the EI program. This financial assistance is invaluable for women and their families, with spouses sometimes sharing part of this time off from work to help with the needs of a newborn and a growing family.[106] Dr. Michael Baker, Professor of Economics at the University of Toronto, discussed the beneficial effects of the EI program’s maternity and parental leave benefits, particularly after the implementation of extended leave in December 2000. His research findings demonstrate that these benefits increased the time women were at home with their children and, in addition, they increased the likelihood that mothers stayed with their pre-birth employer.[107] There are two sources to this job continuity associated with extended leaves: Some women come back to the work force instead of permanently quitting in order to care for their child. Another large share of mothers switches from taking new mostly part-time jobs while their child is young to taking longer leaves before returning full-time to the pre-birth employer.[108] Dr. Baker also pointed out that because mothers are spending longer period of time with their infants, there is also evidence of a positive effect on breast feeding behavior of mothers in Canada. B. Inequities in Maternity/Parental Benefits Despite the positive effects accrued by women from accessing maternity/parental benefits, the Committee heard that there are several inequities that exist. These arise because some women have employers who can ‘top-up’ their maternity/parental benefits. As an example, federal public service employees are entitled to a top-up to 93% of their earnings.[109] Many women do not have access to the same generous employer benefits and have to contend with the EI program’s 55% income replacement rate. Evidence from Statistics Canada suggests that women with lower earnings may not be financially able to stay at home for the duration of their maternity/parental benefits and return to work within four months.[110] According to Professor Lahey: Approximately 25% of women are not able to take their full maternity leave period, even though technically it's been expanded to a year. Those are women who, on average, have incomes of $16,000. The whole group of the 25% earn $20,000 or less, or if they are not single parents, they, with their partner or husband together, earn no more than $40,000 per year. So it's clearly the financially stressed group. There are also figures that show that if a woman has a permanent, full-time job she will almost certainly take the full one-year maternity leave—98% do so.[111] Dr. Leah Vosko also pointed out that women who take their maternity and parental leave may be at risk of losing their employment when they return to work and may not be able to qualify for regular benefits. A woman returning from a year's parental and pregnancy leave may find herself unable to collect any EI benefits if she is laid off in the following months. This is because she is unlikely to have accrued sufficient hours to establish a new claim, especially if her work week is under 35 hours.[112] Certain witnesses did recommend that maternity/parental benefits should be in a separate program and not tied to an employment insurance program, as in the case of the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan. This would mean that maternity/parental benefits and regular benefits would have different qualification requirements and benefit entitlements. Another issue that witnesses raised is that not all mothers have access to maternity/parental benefits and many are excluded from the program. Women who work part-time or in other forms of non-standard work have difficulty qualifying for these benefits.[113] In addition, maternity/parental benefits target women who have a labour force attachment and do not consider women who are stay-at-home mothers. Finally, women who are self-employed are currently excluded from the program. In 2005, the Committee studied the topic of extending maternity and parental benefits to the self-employed.[114] Budget 2009 announced that an Expert Panel will be established to consult Canadians on how to best provide the self-employed with access to EI maternity and parental benefits.[115] C. Maternity/Parental Benefits Reinforce Women’s Role as Caregivers Witnesses pointed out that instead of promoting the sharing of caregiving responsibilities between the two spouses, maternity/parental benefits tend to reinforce women’s caregiving responsibilities. The Committee heard that an incentive is created for the low income earner in the household (usually the female) to take the leave rather than the high-income earner (usually the male). This effect is due to the low rate of income replacement and the low cap for maximum insurable earnings.[116] [T]he program parameters for the caregiving benefits reinforce women taking the leaves rather than men. The low-income replacement rates, for example, reinforce the lower earner taking the leave. So the parameters of the existing parental maternity benefits are not doing a good job of sharing the caregiving workload.[117] The Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) provides a different model than the federal one. The Committee heard that the plan is more generous and offers more flexibility. It has a higher threshold of maximum insurable earnings so that the higher income earner has the option to take parental leave. As well, it offers paternity benefits for the father and includes the self-employed. As a family protection policy, this plan encourages men to share caregiving responsibilities with women. Ms. Vincent provided the following description of QPIP: This program is more generous and also offers flexibility to insured parents: earnings replacement rates can go up to 75% of insurable earnings, and the threshold of maximum insurable earnings is $62,000, compared with only $41,000 under EI. The program also provides for up to five weeks of benefits exclusively to the father. In 2006, 56% of fathers eligible for paternity benefits took advantage of the program in Quebec, compared with only 10% of eligible fathers in the rest of Canada.[118] The Committee heard from several witnesses that the EI program’s maternity/parental benefits should be reformed so that it becomes more accessible, more generous and more flexible. Witnesses recommended that the Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP) be used as a model not only for reforming the EI program but also for extending it to the self-employed. In addition, witnesses recommended that paternity benefits be taken into consideration. However, witnesses disagreed as to whether the contributions for the self-employed should be mandatory, as in the case of QPIP, or voluntary. RECOMMENDATION 14: The Committee recommends that:

The Committee is also concerned that women who are on maternity/parental leave risk being laid off either duration their leave or afte they return to work. Therefore, RECOMMENDATION 15: The Standing Committee on the Status of Women recommends that the government modify the Employment Insurance program for women who are laid off during or following maternity/parental leave so that benefits are calculated based on the number of hours worked prior to maternity/parental leave. V. Sickness Benefits and Compassionate Care Benefits Even though witnesses welcomed the provision of sickness and compassionate care benefits, they raised concerns that the duration of benefits was insufficient. For women who suffer from episodic disabilities[121] and from cancer, 15 weeks of sickness benefits did not address their needs. For people living with HIV/AIDS and other disabilities such as multiple sclerosis and mood disorders, the episode of inability to work can last longer than 15 weeks. And then, according to the 2004 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, 10% of all the people who used all 15 weeks of EI sickness benefits received CPP disability benefits afterwards. This finding suggests that 15 weeks of EI sickness benefits may not be enough.[122] Ms. Denise Page, analyst with the Canadian Cancer Society, explained to the Committee that women who suffer from breast cancer have to undergo surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. In combination, their health care needs add up to more than a year of illness.[123] Witnesses spoke highly of the Compassionate Care Benefits (CCB) introduced in 2004. Ms. Pamela Fancey, Associate Director, Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, informed the Committee that these benefits entail “a positive step toward supporting employees.”[124] She noted the positive effects of the CCB in retaining employees who may have otherwise had to leave the labour force to care for a dying relative.[125] Ms. Fancey, who has also conducted international comparisons of family leave polices, pointed out that because Canada’s CCB is embedded in the EI program, it is limited to those who participate in the labour force. Those who do not participate in the labour force or who do not qualify for CCB due to their employment patterns are excluded. As Ms. Fancey explained, these exclusions do not exist in certain jurisdictions: These noted exclusions do not exist in Sweden, Norway or California, where eligibility is extended to all workers, including part-time and self-employed, provided they have contributed to a national social insurance program, as in the case of Sweden and Norway, or state disability insurance benefits, as is the case in California.[126] The Committee heard that, in comparison to other jurisdictions, Canada’s “dying” criteria is “stringent” making it difficult for claimants to know when it is appropriate to submit a claim: Canada's CCB definition of gravely ill is considered stringent and the process cumbersome in comparison to other jurisdictions. In Canada, the employee's relative must be at risk of dying within 26 weeks and need a medical certificate to that effect signed by a physician. This can at times be difficult to assess, given the sometimes unpredictable nature of the dying process, thereby making it difficult for employees to know when to apply for the leave and when to take the leave itself.[127] However, Ms. Fancey also indicated that Canada’s CCB has an in-built flexibility that allows caregiving to take place either in the community or in an institutional setting, “encompass[ing] the full spectrum from employees who provide emotional support to those who actually perform physical care, regardless of living arrangements.”[128] Another concern that Ms. Fancey raised was in regards to the 55% income replacement rate. She informed the Committee that “[w]omen's short- and long-term financial security may be jeopardized because of the low monetary value and maximum ceiling of the benefit itself.[129] Several witnesses recommended that the current 15-week of duration of sickness benefits needs to be extended. RECOMMENDATION 16: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada extend sickness benefits commensurate with Employment Insurance parental leave. The Committee heard that Compassionate Care Benefits (CCB) duration of six weeks needs to be extended. Witnesses also noted that CCB requirements are too stringent and lack flexibility. Under the current medical proof criteria, a claimant must provide proof showing that the ill family member needs care or support and is at risk of dying within 26 weeks.[130] RECOMMENDATION 17: The Committee recommends that Compassionate Care Benefits be extended commensurate with Employment Insurance parental leave. RECOMMENDATION 18: The Committee recommends that changes be made to the Compassionate Care Benefits so that it responds to the variability of need for care and that these changes be monitored annually to ensure they respond to the needs of caregivers. RECOMMENDATION 19: The Committee recommends that the medical criteria for Compassionate Care Benefits be expanded to include a broader definition of ‘the gravely ill’ encompassing both the severely and chronically ill. RECOMMENDATION 20: The Committee recommends that the medical proof requirements for Compassionate Care Benefits be modified so that they are more flexible. The Committee is concerned that the uptake of the Compassionate Care Benefits is relatively lower than other special benefits. According to the 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, the “number of new compassionate care benefits claims grew by less than 1% (0.5%) in 2007/08, to reach 5,700.”[131] The Committee would like HRSDC to examine further why the uptake for CCB claims is low. VI. Training and Development for Unemployed Women Part II of the Employment Insurance Act commits the federal government to work in concert with provinces and territories to put in place active employment programs to help unemployed Canadians integrate into the labour market. These programs are called Employment Benefits and Support Measures, most of which are delivered through transfer Labour Market Development Agreements between the federal government and the provinces and territories.[132] However, only EI beneficiaries or those who have received regular or maternity/parental benefits in the past three or five years respectively are eligible for this support. As several witnesses have noted, women tend to be excluded from such programs since many do not qualify for EI. Budget 2009 invests $500 million over two years in a Strategic Training and Transition Fund (STTF) to support individuals who do not qualify for EI training, such as the self-employed or those who have not been in the labour force for a prolonged period of time. According to information submitted by HRSDC, the STTF will be administered through existing Labour Market Development Agreements. Provinces and territories are to report on this dedicated funding by developing an annual plan with a description of eligible beneficiaries; a description of priority areas; and, a description of eligible programs. In addition, provinces and territories are to measure program performance by collecting performance indicators on eligible beneficiaries, the types of interventions provided, and the outcomes of the interventions funded through the STTF. Based on these annual and quarterly updates from the provinces and territories, the federal government will report nationally on the results of the STTF. [133] Ms. Janice Charette, Deputy Minister of HRSDC, indicated to the Committee that the Department can provide gender disaggregated information on various clients being served under the Employment Benefits and Support Measures. We are in the process of negotiating agreements with provinces and territories right now, who, as you said, will deliver the Strategic Training and Transition Fund. I know we're going to be tracking clients who benefit. Certainly for the employment benefits and supports were delivered under Part II of Employment Insurance Program, the Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDA), we do track by gender.[134] RECOMMENDATION 21: The Committee recommends that Human Resources and Skills Development Canada make publicly available on a monthly basis gender disaggregated data on the recipients of Employment Benefits and Support Measures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. RECOMMENDATION 22: The Committee recommends that:

The Committee heard that women and men are paying into EI and not qualifying for benefits. In 2006, 15% of female paid workers contributed to the EI program but did not work sufficient hours to qualify for benefits, compared to only 8% of men.[135] The EI program provides a premium refund for those whose earnings are less than $2,000.[136] However, this threshold may be too low. An alternative to raising the insurable earnings refund would be for the federal government to introduce an earnings exemption not unlike that found in the Canada Pension Plan. Recommendations were made to introduce a year’s basic exemption to EI premiums based on the individual’s earnings. As Dr. Schirle indicated: [T]here are several people, male and female, who will never qualify for EI benefits, yet have to make contributions. It seems unreasonable to require that people pay insurance premiums toward insurance they could never benefit from. For example, to be eligible for regular EI benefits in a high unemployment region, a typical person must have had 420 insurable hours in the previous 52 weeks. On average, this person must have worked more than 8 hours per week at all jobs combined. Introducing a year’s basic exemption to EI premiums, based on an individual’s annual earnings, with all, not a single employer, might be a reasonable solution to consider here.[137] VIII. Reforming the EI program—A New Architecture The Committee heard from several witnesses that the EI program needs to be reformed to account for women’s income insecurities, labour market realities and caregiving responsibilities. As witnesses noted, the EI program has to become an integral part of Canada’s social safety net. The Committee heard that many women who do not qualify for EI benefits or who exhaust their benefits may end up on social assistance.[138] Mr. Battle proposed to the Committee that the EI program be changed so that an additional program is developed, a temporary income program. The temporary income program would serve people who do not qualify for EI. In other words, we would have now a two-part system. One part would be employment insurance, funded through premiums the way it is now, but it would be a stronger program. It would not have variable entrance requirements. There wouldn't be the perversion of the regional aspect to it. And there would be a new income-tested program, funded through general revenues—this again would be a federal one—that would help unemployed people who aren't able to qualify for an employment insurance program.[139] [65] Dr. Martha MacDonald, Professor, Economics Department, Saint Mary's University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0925). [66] Kathleen Lahey, Faculty of Law, Queen's University, FEWO Evidence, February 24, 2009 (1125). [67] Dr. Tammy Schirle, Assistant Professor, Department of Economic, Wilfrid Laurier University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0940). [68] Ibid. [69] “Community Unemployed Help Centre Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women”, March 31, 2009, FEWO Evidence. [70] Ms. Marie White, National Chairperson, Council of Canadians with Disabilities, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1135). [71] Lesiuk v. Canada (March 22, 2001), CUB 51142 http://www.ae-ei.gc.ca/policy/appeals/cubs/50000-60000/51000-51999/51142e.html, Ms. Marie White, National Chairperson, Council of Canadians with Disabilities, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1135). [72] Ms. Lucya Spencer, Ontario Council of Agencies Serving Immigrants, FEWO Evidence, March 10, 2009 (1205). [73] Appendix 2 and Appendix 4 provide the Table of Weeks of Benefit under EI and UI, respectively. [74] Ms. Janice Charette, Deputy Minister of HRSDC, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (1135). [75] Ibid. [76] HRSDC, 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://www.rhdcc.gc.ca/eng/employment/ei/reports/eimar_2008/index.shtml. [77] Dr. Leah Vosko, Canada Research Chair in Feminist Political Economy, York University, FEWO Evidence, March 26, 2009 (1215). [78] Dr. Leah Vosko, “Presentation to House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women”, FEWO Evidence, March 26, 2009. [79] Ms. Carole Vincent, Senior Research Associate, Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0945) [80] Dr. Martha MacDonald, Professor, Economics Department, Saint Mary's University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0925). [81] Ibid. (0930). [82] Ibid (1025). [83] Ibid. [84] The Gazette, “Regulations Amending the Employment Insurance Regulations,” September 4, 2008, http://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2008/2008-09-17/html/sor-dors257-eng.html, accessed April 13, 2009. [85] HRSDC, EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/employment/ei/reports/eimar_2008/chapter5_2.shtml#_ftnref42. [86] Mr. Paul Thompson, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Skills and Employment Branch, Department of Human Resources and Skills Development, FEWO Evidence, March 10, 2009 (1110). [87] Variable entrance requirements for the period of April 12, 2009 to May 09, 2009 can be found at this HRSDC website: http://srv129.services.gc.ca/eiregions/eng/rates_cur.aspx. [88] Mr. Ken Battle, President, Caledon Institute of Social Policy, FEWO Evidence, March 5, 2009 (1200). [89] Liberal Party members voted against this recommendation. [90] Employment Insurance Act, 13. [91] Ms. Sue Calhoun, President, Canadian Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs, FEWO Evidence , March 26, 2009 (1230). [92] Government of Canada, Government Response to the Fifth Report of the Standing Committee on the Status of Women, “Interim Report on the Maternity and Parental Benefits under Employment Insurance: the Exclusion of Self-Employed Workers ”, September 18, 2006, /HousePublications/Publication.aspx?DocId=2335206&Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=39&Ses=1. [93] Ibid. [94] Ms. Lucille Harper, Executive Director, Antigonish Women's Resource Centre, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1105). [95] Mr. Ken Battle, President, Caledon Institute of Social Policy, FEWO Evidence, March 5, 2009 (1125). [96] As explained earlier in Chapter 1, average weekly insurable earnings are calculated over the larger of the following two divisors: the number of weeks in which a claimant had earnings in the last 26 weeks of the qualifying period (also called the maximum rate calculation period) or the divisor (i.e. 14 to 22 depending on the regional rate of unemployment). [97] Dr. Martha MacDonald, Professor, Economics Department, Saint Mary's University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0925). [98] According to section 7(4) of the Employment Insurance Act: An insured person is a new entrant or a re-entrant to the labour force if, in the last 52 weeks before their qualifying period, the person has had fewer than 490 (a) hours of insurable employment; (b) hours for which benefits have been paid or were payable to the person, calculated on the basis of 35 hours for each week of benefits; (c) prescribed hours that relate to employment in the labour force; or (d) hours comprised of any combination of those hours. According to Section 7(4.1) of the Employment Insurance Act: An insured person is not a new entrant or a re-entrant if the person has been paid one or more weeks of special benefits referred to in paragraph 12(3)(a) or (b) in the period of 208 weeks preceding the period of 52 weeks before their qualifying period or in other circumstances, as prescribed by regulation, arising in that period of 208 weeks. [99] Dr. Leah Vosko, Canada Research Chair in Feminist Political Economy, York University, FEWO Evidence, March 26, 2009 (1255). [100] Kathleen Lahey, Faculty of Law, Queen's University, FEWO Evidence, February 24, 2009 (1130). [101] Service Canada, “Employment Insurance (EI) Pilot Project for New Entrants and Re-Entrants,” http://www.servicecanada.gc.ca/eng/ei/information/access_ei.shtml, accessed April 12, 2009. [102] HRSDC, EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/employment/ei/reports/eimar_2008/chapter5_2.shtml#_ftnref42. [103] Ms. Carole Vincent, Senior Research Associate, Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0955). [104] Mr. Neil Cohen, Executive Director, Community Unemployed Help Centre, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1205) [105] Ms. Janice Charette, Deputy Minister of HRSDC, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (1120). [106] Mrs. Verna Heinrichs, As an Individual, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1150). [107] Dr. Michael Baker, Professor, Department of Economics, University of Toronto, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009, (0905-0910). [108] Michael Baker and Kevin Milligan, “How does job-protected maternity leave affect mothers’ employment?” July 2008, p. 30. [109] Mr. Richard Shillington, “Presentation on Maternity and Parental Benefits under Employment Insurance,” FEWO Evidence, February 26, 2009. [110] Katherine Marshall, “Benefiting from extended parental leave,” Perspectives on Labour and Income, Statistics Canada, March 2003, p. 9. [111] Professor Kathleen Lahey, Faculty of Law, Queen's University, FEWO Evidence, February 24, 2009 (1205) [112] Dr. Leah Vosko, Canada Research Chair in Feminist Political Economy, York University, FEWO Evidence, March 26, 2009 (1150). [113] Ibid. (1220). [114] Standing Committee on the Status of Women, Interim Report on the Maternity and Parental Benefits Under Employment Insurance: The Exclusion of Self-Employed Workers, November 2005, /content/Committee/381/FEWO/Reports/RP2148183/FEWO_Rpt05/FEWO_Rpt05-e.pdf. [115] Budget 2009, http://www.budget.gc.ca/2009/plan/bpc3b-eng.asp. [116] Ibid. [117] Dr. Martha MacDonald, Professor, Economics Department, Saint Mary's University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0930). [118] Ms. Carole Vincent, Senior Research Associate, Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0950). [119] For greater clarity, this recommendation does not apply to the province of Quebec which finances its own parental benefits. [120] Ibid. [121] An episodic disability is marked by fluctuating periods and degrees of wellness and disability (see: Canadian Working Group on HIV and Rehabilitation http://www.hivandrehab.ca/EN/resources/description_episodic_disabilties.php). [122] Ms. Carmela Hutchison, President, DisAbled Women's Network of Canada, FEWO Evidence, March 12, 2009 (1130). [123] Mrs. Denise Page, Health Policy Analyst, Canadian Cancer Society, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1120). [124] Ms. Pamela Fancey, Associate Director, Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, FEWO Evidence, March 31, 2009 (1140). [125] Ibid. [126] Ibid. [127] Ibid. (1145). [128] Ibid. [129] Ibid. (1150). [130] HRSDC, EI Compassionate Care Benefits, http://www.servicecanada.gc.ca/eng/ei/types/compassionate_care.shtml#Who. [131] HRSDC, 2008 EI Monitoring and Assessment Report, http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/employment/ei/reports/eimar_2008/chapter5_1.shtml. [132] HRSDC, Report on Plans and Priorities. 2009-2010 Estimates, p. 48. [133] Submission from HRSDC, FEWO Evidence, May 1, 2009. [134] Ms. Janice Charette, Deputy Minister of HRSDC, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (1155). [135] Ms. Carole Vincent, Senior Research Associate, Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0950). [136] According to section 96(4) of the Employment Insurance Act If a person has insurable earnings of not more than $2,000 in a year, the Minister shall refund to the person the aggregate of all amounts deducted as required from the insurable earnings, whether by one or more employers, on account of the person’s employee’s premiums for that year. [137] Dr. Tammy Schirle, Assistant Professor, Department of Economic, Wilfrid Laurier University, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009 (0940). [138] For example, Ms. Jane Stinson, President, Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women and Ms. Bonnie Diamond, Co-Chair, Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action, FEWO Evidence, April 2, 2009. [139] Mr. Ken Battle, President, Caledon Institute of Social Policy, FEWO Evidence, March 5, 2009 (1130). |