Appearance

before the Standing Committee on Access

to

Information, Privacy and Ethics

April 29, 2008

Statement

Recommendations

Recommendation Number 1

Recommendation Number 2

Recommendation Number 3

Recommendation Number 4

Recommendation Number 5

Recommendation Number 6

Recommendation Number 7

Recommendation Number 8

Recommendation Number 9

Recommendation Number 10

Reforming the Privacy Act – A Chronology of Recommendations

Proposed

Immediate Changes to the Privacy Act

Appearance

before the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics

April 29, 2008

Statement by

Jennifer Stoddart

Privacy Commissioner of Canada

(Check against

delivery)

Introduction

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, for inviting me to address you

once again on the issue of Privacy Act reform. I’m joined by Raymond

D’Aoust, Assistant Commissioner for the Privacy Act, and Patricia Kosseim, our General Counsel.

In 2006, as you may recall, my Office tabled with the Committee a comprehensive

document entitled Government Accountability for Personal Information:

Reforming the Privacy Act. More recently, for the purposes of our April 17 appearance,

we prepared an Addendum to that document, discussing how events of the past two

years illustrate the ongoing need for reform of the Act. At that time, I

provided you with a list of ten recommended changes to the Privacy Act.

These changes were outlined in my opening statement to the Committee.

Further to a request from the Committee, my Office has now prepared a third document,

which provides greater detail on the rationale supporting our ten “quick fix”

recommendations.

I would like to make it clear that the changes we are currently proposing are not

meant to be the definitive statement on Privacy Act reform. This is

most emphatically not the case – the Privacy Act is in desperate need of

a full Parliamentary review and complete overhaul.

I realize, however, that a full Parliamentary review of the Act may not happen

for some time. While we wait for a comprehensive modernization initiative,

there are some relatively simple changes we could make which would be of

significant benefit to Canadians.

Some of the changes we are suggesting would simply incorporate into law existing

Treasury Board Secretariat policies and practices. Other recommendations

correspond to privacy requirements found in PIPEDA – Canada’s private sector privacy law.

“Quick Fix” Recommendations

I’d like to provide a quick overview of the ten recommendations:

-

Parliament should create a requirement in the Privacy Act for government

departments to demonstrate the need for collecting personal information. This

“necessity test” is already included in Treasury Board policies as well as PIPEDA.

It is an internationally recognized privacy principle found in modern privacy

legislation around the world.

-

The role of the Federal Court should be broadened to allow it to review all grounds

under the Privacy Act, not just denial of access.

-

Parliament should enshrine into law the obligation of Deputy Heads to carry out a Privacy

Impact Assessment – or PIA – before a new program or policy is implemented.

-

The Privacy Act should be amended to provide my Office with a clear public education

mandate. PIPEDA contains such a mandate and it is only logical that the Privacy Act

contain a similar mandate for the public sector.

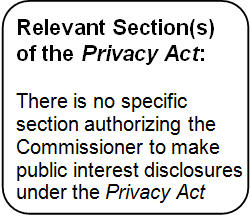

-

The Act should be further amended to provide my Office with increased flexibility

to publicly report on the privacy management practices of the federal

government. As it now stands, we are limited to reporting to Parliament and

Canadians through annual or special reports.

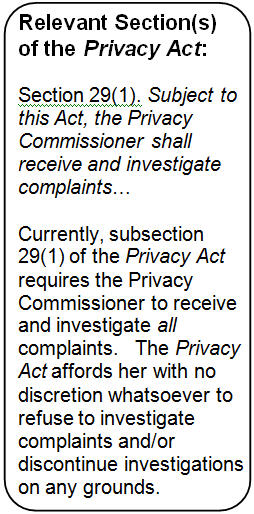

-

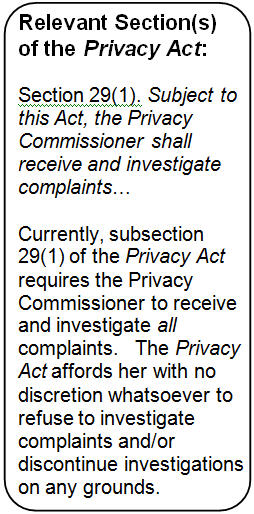

My Office should have greater discretion to refuse or discontinue complaints if an

investigation would serve no useful purpose or is not in the public interest.

This would allow us to focus investigative resources on privacy complaints

which are of broad systemic interest and affect the interests of a significant

number of Canadians.

-

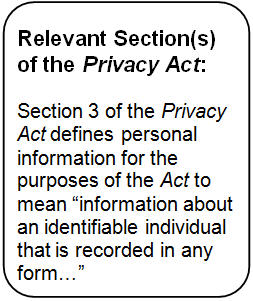

The Act should be aligned with PIPEDA by eliminating the restriction that

the Privacy Act applies only to “recorded” information. At the moment,

for example, personal information contained in DNA and other biological samples

is not explicitly covered.

-

Annual reporting requirements of government departments and agencies under section 72

of the Act could be strengthened by requiring these institutions to report to

Parliament on a wider spectrum of privacy-related activities.

-

The Act should include a provision requiring an ongoing five-year Parliamentary

review of the Privacy Act, as is the case with PIPEDA.

-

The Act should be strengthened with respect to the provisions governing the disclosure of

personal information by the Canadian government to foreign states. Treasury

Board Secretariat (TBS) has taken some important steps by providing guidance on

information sharing agreements and outsourcing of personal data processing.

However, we need privacy protections related to cross-border information

sharing enshrined into law.

Privacy Education in the Public Service

Our Office also believes more needs to be done to ensure that program managers in the

public services are aware of their responsibilities under the Privacy Act and related TBS guidelines.

I urge the Government to carry out a comprehensive assessment of the privacy

training provided to public servants. It is critical that privacy issues are

thoroughly addressed in leadership, professional development and management

courses aimed at all levels of the public service.

Conclusion

In closing I would like to re-emphasize that although we are proposing ten “quick

fix” changes, the Privacy Act is still very much in need of a major

review and overhaul. There are many other problems with the Act that require

attention, including the need for proper security safeguards for personal

information and mandatory breach notification. This said, however, making the

adjustments to the Act that we are suggesting would certainly help to enhance

the level of personal information protection in the federal public sector.

Thank you for inviting me to share some further thoughts on this important subject.

We would be pleased to answer any questions.

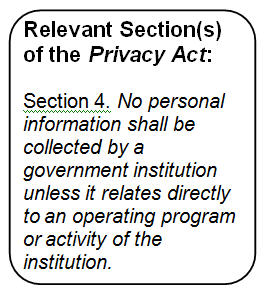

Recommendation Number 1: Create a

legislative “necessity test” which would require government institutions to

demonstrate the need for the personal information they collect.

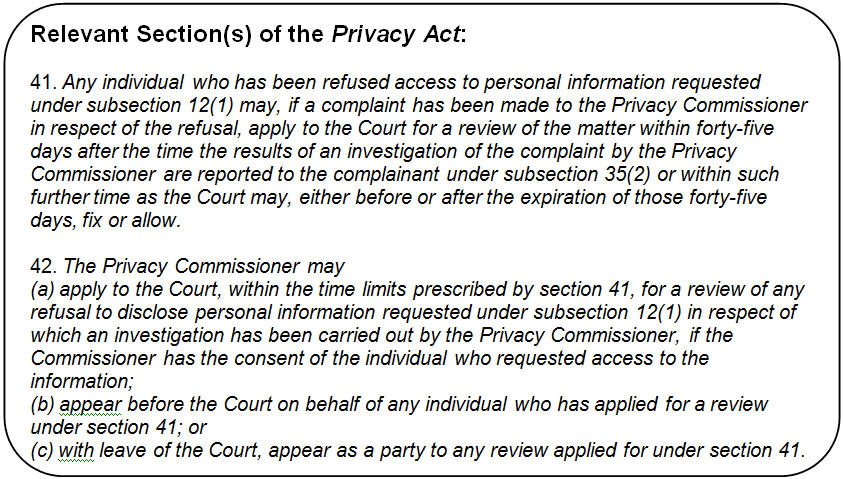

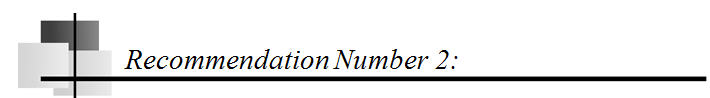

Recommendation Number 2: Broaden the

grounds for which an application for Court review under section 41 of the Privacy

Act may be made to include the full array of privacy rights and protections

under the Privacy Act and give the Federal Court the power to award

damages against offending institutions.

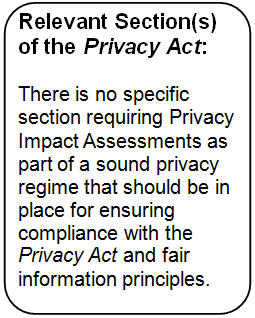

Recommendation Number 3: Enshrine

a requirement for heads of government institutions subject to the Privacy

Act to assess the privacy impact of programs or systems prior to their

implementation and to publicly report assessment results.

Recommendation Number 4: Amend the Privacy

Act to provide the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada with a clear public education mandate.

Recommendation Number 5: Provide

greater discretion for the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada to report publicly on the privacy

management practices of government institutions.

Recommendation Number 6: Provide

discretion for the Privacy Commissioner to refuse and/or discontinue complaints

the investigation of which would serve little or no useful purpose, and would

not be in the public interest to pursue.

Recommendation Number 7: Amend the Privacy

Act to align it with the Personal Information Protection and Electronic

Documents Act by eliminating the restriction that the Privacy Act applies to

recorded information only.

Recommendation Number 8: Strengthen the

annual reporting requirements of government departments and agencies under

section 72 of the Privacy Act, by requiring these institutions to report

to Parliament on a broader spectrum of privacy-related activities.

Recommendation Number 9: Introduction

of a provision requiring an ongoing five year Parliamentary review of the Privacy

Act.

Recommendation Number 10: Strengthen the

provisions governing the disclosure of personal information by the Canadian government

to foreign states.

Create a legislative

“necessity test” which would require government institutions to demonstrate the

need for the personal information they collect.

Background:

A far more effective expression of privacy rights, typical of modern data protection

laws, is to require that the collection of information be reasonable and

necessary for the program or activity. This standard has been adopted in other

legislation both in Canada and abroad. Treasury Board policy states that there

must be a demonstrable need for each piece of personal information collected in

order to carry out the program or activity. Principle 4.4 of the Personal

Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (“PIPEDA”) requires

the collection to be limited to that which is necessary for the purposes

identified. The standard set in section 12 of the CSIS Act limits

information collection “to the extent that it is strictly necessary” to that

institution’s mandate.

Almost all provinces and the territories have adopted a model in the public sector

legislation that requires that one of three conditions be met: (i) the

collection is expressly authorized by statute; (ii) the information is

collected for the purpose of law enforcement; or (iii) the information relates

directly to and is necessary for an operating program or activity.

Consideration should also be given to including a requirement that the government institution

must collect personal information in the least intrusive and most transparent

manner possible, to address technologies which are inherently privacy-invasive

such as video surveillance, GPS, biometrics, etc.

Rationale:

Giving Effect to the Fundamental Right to Privacy

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized on numerous occasions that privacy

interests are worthy of protection under the Charter[1] and that the Privacy

Act has quasi-constitutional status.[2] The current wording of section 4 of the Privacy Act sets a

disproportionately low standard for the fundamental rights at the heart of the Privacy

Act. By building in better controls at the collection point, there is less

potential for misusing and disclosing personal information.

Providing Stronger Legislative Controls around the

Collection of Personal Information

The public reaction to HRDC’s Longitudinal Labour Force File provides a graphic

reminder of the need to provide better legislative controls around the

collection of personal information. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner

(the “OPC”) reported on this matter in its 1999-2000 Annual Report. The

department had assembled an extensive database for research purposes containing

personal information on millions of individuals. While the department argued

that it was in compliance with the literal collection standard set by the Privacy

Act, the OPC did not accept that all of the information contained in that

database was directly relevant and necessary to HRDC’s operating programs and

policy activities. Since then, the database has been dismantled and the

department has been steadily improving in its privacy management practices.

In another of its recommendations, the OPC urges that the Privacy Act be

broadened to permit an individual to seek court review for all aspects of

personal information collection, use and disclosure. An appropriate collection

standard, combined with a right of court review, would be an important first

step in creating a more meaningful legal framework.

Broaden the grounds for which an application for Court

review under section 41 of the Privacy Act may be made to include the

full array of privacy rights and protections under the Privacy Act and

give the Federal Court the power to award damages against offending

institutions.

Background:

Under section 41 of the Privacy Act, the Federal Court may only review

a refusal by a government institution to grant access to personal information

requested by an individual under section 12 of the Privacy Act. Although

the Commissioner can investigate complaints concerning the full array of rights

and protections under the Privacy Act and make recommendations to the

government institution, if the response of the institution is not satisfactory,

neither the individual nor the Privacy Commissioner has the possibility to

apply to the Federal Court for enforcement and remedy.

The inability of the Privacy Act to provide effective remedies for

violations of privacy rights was confirmed by the Federal Court in Murdoch

v. Canada (Royal Canadian Mounted Police), [2005] 4 F.C.R. 340. In

that case, the RCMP wrongfully disclosed personal information regarding Mr.

Murdoch to his employer. The OPC concluded that Mr. Murdoch’s complaint was

well-founded, and he tried to seek a Court remedy. However, the Court

concluded that, as it is currently structured, the Privacy Act did not

give Mr. Murdoch the right to seek a remedy for the breach of his privacy.

Furthermore, the Court noted that the power of the Federal Court to grant a

remedy is effectively restricted to granting access to personal information.

Rationale:

Giving Effect to the Fundamental and Quasi-Constitutional

Status of Privacy Rights

Broadening Federal Court review would confirm that privacy rights in the public sector and

the private sector are equally important, ensure that government institutions

respect every Canadian’s right to have their personal information collected,

used and disclosed in accordance with the Privacy Act and give full

weight to the privacy rights of individuals in a free and democratic society.

The Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed that the purpose of the Privacy

Act is to protect the privacy of individuals with respect to personal

information about themselves held by a government institution, this purpose

being of such importance to warrant characterizing the Privacy Act as

“quasi-constitutional” because of the role privacy plays in the preservation of

a free and democratic society. [3]

Keeping Government Accountability Through a Meaningful

Review Mechanism

Implementing our recommendation would give Canadians the same rights regarding their

personal information collected, used or disclosed by their own government

institutions that they hold vis-à-vis private-sector organizations exercising

commercial activities under PIPEDA. Government institutions

should be even more open and accountable with respect to their personal

information handling practices, and increasing government accountability

clearly requires strengthened privacy rights when it comes to how government

handles the personal information of Canadians. Our recommendation is essential

to achieving meaningful government accountability and transparency.

Directly Protecting Privacy Rights Through the Intended

Legislation

The Supreme Court of Canada has held that a third-party to an access to information

request made under the ATI Act can apply to the Federal Court for a

hearing in respect of a government institution’s disclosure of personal

information.[4]

Given that the Supreme Court of Canada has held that the right to privacy is paramount over

the right of access to information, how can it be that a third-party can

appear before the Federal Court with respect to the disclosure of another

person’s personal information under the ATI Act, but that an individual

cannot even seek enforcement and a remedy for a violation of the fundamental

right of privacy under the Privacy Act vis-à-vis his or her own personal

information? Broadening Federal Court review under the Privacy Act would

address this unintended consequence.

There is No Right Without a Remedy

Every right needs a remedy in order to have meaning. This is especially so with

respect to a fundamental right such as privacy. Implementing our

recommendation would ensure that the Federal Court can review the full array of

fundamental rights and protections under the Privacy Act, including

inappropriate collection, use or disclosure of personal information, failure to

maintain up-to-date and accurate data, improper retention or disposal, and

denials of access or correction by government institutions. It would also

ensure that the Federal Court may award damages in cases where, for example,

the inappropriate use or disclosure of personal information causes

embarrassment or other harms to the individual concerned.

The Need for Court Guidance

Implementing our recommendation would allow the Federal Court to provide needed guidance on

what constitutes inappropriate collection, use or disclosure of personal

information.

Enshrine a requirement for heads of government institutions

subject to the Privacy Act to assess the privacy impact of programs or

systems prior to their implementation and to publicly report assessment

results.

Background:

In May 2002, the Treasury Board Secretariat (the “TBS”) introduced an

administrative policy on Privacy Impact Assessments. The policy was adopted to

assure Canadians that privacy principles would be taken into account when there

are proposals for programs and services that raise privacy issues, throughout

the design, implementation and evolution of those initiatives. This represents

a core component of a privacy compliant regime since the policy requires that

institutions demonstrate that their collection, use and disclosure of personal

information respect the Privacy Act.

Rationale:

Given the unevenness with which government institutions are implementing the Privacy

Impact Assessment policy, there should be a legal requirement for Privacy

Impact Assessments to ensure that they are done on a consistent and timely

basis.

Ensuring Compliance with the Privacy Impact Assessment

Policy

In the OPC’s 2007 audit of government compliance with the Privacy Impact

Assessment policy, it was ascertained that institutions are not fully meeting their

commitments under the policy. Privacy Impact Assessments are not always

conducted when they should be. They are frequently completed well after program

implementation, or not at all. Present PIA reporting and notification standards

provide little assurance or information to Canadians seeking to understand the

privacy implications of government services or programs.

Furthermore, the Policy in and of itself does not provide assurance that privacy impacts are

being assessed for pervasive and strategic government-wide initiatives.

Knowing the potential privacy impacts of proposed policies and plans would

provide government (TBS and/or Cabinet) with an early opportunity to modify

programs or systems to protect the personal information of individuals in Canada, and perhaps

reduce future costs associated with program or system changes.

Strengthening Accountability

Privacy Impact Assessments should be submitted to the OPC for review prior to program

implementation. Review by the OPC provides independent and objective

recommendations as to how privacy could be better protected while meeting

program objectives in less intrusive ways.

Ensuring the Transparency of Government Programs

Privacy Impact Assessments are vitally important and should be a key element of a

privacy management framework enshrined in legislation. Canadians should be

assured in law that privacy risks will be identified and mitigated as an

integral part of administering federal government programs. To this end,

institutions should be required to publicly report assessment results. In

making the privacy implications of programs more transparent, Canadians will

have an opportunity to voice their concerns and will have assurance that

privacy risks are being addressed.

Amend the Privacy Act to provide the OPC with a clear

public education mandate.

Background:

While PIPEDA provides the OPC with a public education mandate, the Privacy

Act does not do so explicitly. Section 24 of PIPEDA states that

“the Commissioner shall: (a) develop and conduct information programs to foster

public understanding…; (b) undertake and publish research that is related to

the protection of personal information, including any such research that is

requested by the Minister of Industry; (c) encourage organizations to develop

detailed policies and practices, including organizational codes of practice…;

and (d) promote, by any means that the Commissioner considers appropriate, the

purposes of this Part.”

Rationale:

While the OPC’s central function under the Privacy Act is the investigation

and resolution of complaints, the OPC also needs to advance privacy rights by

other means – through research, communication and public education. The

Commissioner lacks the legislative mandate under the Privacy Act to

educate the public about their informational privacy rights with respect to

information held by federal government institutions. The Commissioner should

be equally empowered to sensitize business, government and the public under the Privacy Act.

Case Summaries on Public Sector Personal Information

Management

Currently, the main vehicle for reporting on cases is the Annual Report under the Privacy

Act. However, with a more explicit public education mandate and more

flexible means for public reporting, the OPC could publish a compendium of

significant cases that fall under the Privacy Act, notably in the areas

of national security, law enforcement, and health. Several civil society

groups with an interest in privacy promotion have urged the OPC to make more

timely public reports on the state of governmental surveillance activities and

how these activities may impact on privacy.

Periodic Assessments of Departmental Privacy Performance

The OPC wishes to foster a more informed public debate of the federal government’s

role in areas involving the sharing of personal information between agencies

and jurisdictions. A clear public education authority would allow the OPC to

publish public advisories and education material on significant policy and

legislative measures with “personal information” components.

Support the Learning Objectives of Informational Rights

Professionals

Surveys carried out by Treasury Board Canada indicate there are significant learning

needs on the part of Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) professionals,

pointing to the increased number and complexity of cases, as well as to the

number of new organizations being covered by the Privacy Act as a result

of the adoption of the Federal Accountability Act. The surveys also

reveal—corroborated by the OPC’s own audit and review work—that learning needs

are not being addressed by the current learning infrastructure. By making more

information available in a more timely way, the OPC will become a valuable

source of information on the need for a more consistent approach to privacy

management across the federal government.

Broader Parameters for the OPC’s Research Program

Better research into public sector personal information management is needed to inform

public policy. Section 24 of PIPEDA allows the OPC to undertake and

publish research that is related to the protection of personal information in

the private sector, with a specific funding envelope. Under this education

mandate, the OPC has put in place a comprehensive Research Contributions Program

which has allocated over $1,000,000 to more than 30 privacy research

initiatives in Canada, resulting in extensive studies on key privacy issues.

These research papers are publicly available on the OPC website. A similar

mandate should exist under the Privacy Act for research relating to

public sector matters.

Benefits the Citizens and Residents of Canada

A clearer public education mandate for the OPC would allow for more extensive and

better informed public dialogue on federal privacy management in areas of

critical importance to the right to privacy. It would also ensure a more

consistent approach to privacy compliance by addressing the learning needs of

informational rights professionals.

Provide greater discretion for the OPC to disclose

information in the public interest on the privacy management practices of

government institutions.

Background:

Pursuant to the Federal Accountability Act, the OPC is now subject to both the ATI

Act and the Privacy Act. As a result, there is now a public right

of access under the ATI Act to certain information contained in OPC

investigation files, and an individual right of access to personal information

in such files under the Privacy Act. The right of access arises only

once the OPC has completed its investigation, thus respecting the need to

maintain confidentiality of ongoing investigations.

No changes were made by the Federal Accountability Act to the provisions in

the Privacy Act that govern the Commissioner’s authority to initiate a

public release of its investigation activities and findings. As a result, the

only clear legislative vehicles available to the OPC for public reporting

purposes are the annual and special reporting provisions.

Rationale:

Serving the Public Interest and Meeting Public

Expectations

It would be consistent with the recent amendments to the ATI Act and Privacy

Act granting a right of access to information in OPC investigation files,

to permit the OPC to release information on its own initiative concerning the

personal information management practices of a government institution where

this serves the public interest.

There is a public expectation that the OPC will investigate and report on matters of

public interest. This is particularly so where the privacy issue is already in

the public domain. The OPC has been hampered in its ability to speak with the

press, with the public, and even with Members of Parliament, due to the

existing confidentiality constraints in the Privacy Act. Furthermore, a

public interest disclosure discretion would allow for more timely and relevant

disclosure rather than having to wait until the end of the reporting year when

the information may have become moot, stale or largely irrelevant.

Educating Canadians

Strengthening the ability to report publicly is an integral component of a strong public

education mandate. Under PIPEDA, the legislated public education

mandate is accompanied by the discretion to disclose information concerning the

personal information management practices of an organization if the

Commissioner considers that it is in the public interest to do so.

Upholding Public Confidence

The discretion to report publicly under PIPEDA has been an invaluable tool for the

OPC in advancing public understanding, providing public assurances, and

restoring public confidence where required. The discretion to make a public

interest disclosure has been used responsibly and judiciously by the OPC, after

due consideration of the various interests at play.

Provide discretion for the Privacy Commissioner to refuse and/or

discontinue complaints the investigation of which would serve little or no

useful purpose, and would not be in the public interest to pursue.

Background:

At the time the OPC requested and received additional funding in 2006, it was the hope that the

generous influx of new resources would enable the Office to reduce the lengthy

and persistent delays associated with having to investigate all individual complaints

that come in the door, while at the same time, focus efforts towards the more

systemic and pervasive privacy threats facing modern society as a whole.

Despite the progress the OPC has made to date, and notwithstanding plans to

take these efforts to the next level, valuable Office resources are

still being disproportionately consumed by having to open and investigate all

individual complaints on a first-come first-serve basis. The waste of public

resources is particularly taxing in cases where the complaints appear to have

no merit, the central issue is clearly not privacy but some different dispute

between the parties, the Office’s intervention would serve no useful purpose

and/or a full-scale investigation into the matter would not be in the public interest.

As concrete examples of some of the kinds of complaints the OPC receives, relatively little

is gained by investigating and/or re-investigating:

-

repetitive issues that come up and have already been clearly decided in past cases (e.g.

legitimate collection and use of Social Insurance Numbers);

-

moot time complaints where the individual has since received the information

requested (e.g. where access was already provided, though technically out of

time and at no disadvantage to the individual);

-

frequent complaints brought forward by the same individual who has an obvious “axe to

grind” against an government institution (e.g. where contentious labour or

employment issues constitute the real dispute between the parties which could

be more effectively dealt with through other, more appropriate procedures);

-

multiple complaints brought by many individuals in respect of the same incident (e.g. a

data breach involving personal information of many individuals which is already

well documented and need not be re-investigated only to confirm what is already

known);

-

issues that have already been recognized and addressed by the government institution

(e.g. effective remedial action has already been taken).

Rationale:

More Effective Use of Limited Resources

Greater discretion at the front end of the intake function would enable the

Commissioner to concentrate her limited available resources on complaints that

raise systemic issues and have broader, more significant impact on the state of

personal information management across the Federal Government.

Traditionally, privacy issues have come up through the individual complaint system as a result

of discrete informational transactions between individuals and their

governments. Today, major privacy issues arise from more systemic threats

resulting from the encroachment of national security and law enforcement

initiatives, multiple trans-border data flows, sophisticated data-mining and

data-matching programs, and rapidly-advancing information technologies,

particularly those enabled by the internet. Such new and emerging threats

affect society as a whole, on such a daily and pervasive level, and in such

complex and non-transparent fashion, that in most cases, the average person

would not even know about them, let alone complain about them.

Data protection authorities around the world recognize that they must increasingly direct their

efforts at curbing these massive threats at their source, as these emerge,

rather than wait for an individual to bring a complaint about them and deal

with them as they make their way up the long queue. Many data protection

authorities in Canada and elsewhere face similar challenges in having to treat

all complaints received indiscriminately, with no ability to dismiss or

discontinue some of them early on where no public interest would be served by

investigating or continuing to investigate them. We are all concerned about

the cost of carrying out investigations that amount to no useful purpose and

the corresponding opportunity cost of not dealing more effectively with

the growing number of broad and systemic issues that are far more pervasive and

pose much greater threat to privacy rights.

Focussing Investigative Resources on Privacy Issues that

are of Broader Public Interest

The UK Commissioner recently asked the British Parliament for the right to investigate only

when an issue is in the public interest. In like manner, the US Federal

Trade Commission (the “FTC”) does not accept complaints from individuals but uses

them to track systemic issues warranting FTC intervention. Here in

Canada, the Canadian Human Rights Act, the Public Servants Disclosure Protection

Act and the Accountability Act as well as the Quebec Private

Sector Act allow those Commissioners to

refuse or cease to examine a matter if the application is frivolous, made in

bad faith, could be better dealt with in another forum or where further

investigation would clearly serve no purpose.[5] In

November 2007, the Alberta Select Special Review Committee recommended that Alberta’s Personal

Information Protection Act be amended “to provide

the Commissioner with explicit authority to discontinue an investigation

or a review when the Commissioner believes the complaint or request for review

is without merit or where there is not sufficient evidence to proceed.”[6] More recently, the

British Columbia Special Review Committee recommended an identical amendment to

B.C.’s Personal Information Protection Act, as well as a further

clarification “that the Commissioner has the discretion not to proceed with an

inquiry in certain circumstances and the authority to reasonably determine his

own process.”[7]

The OPC requests that the Committee recommend granting similar discretion for the Commissioner:

one which gives the Commissioner greater discretion at the front-end to refuse

complaints and/or close complaints early if their investigation would serve no

useful purpose, thereby allowing the Office to focus its investigative

resources on privacy issues that are of broader public interest. The

OPC has asked the government that it be given the same discretion under PIPEDA and

it makes sense that both Acts should mirror each other in this respect.

Amend the Privacy Act to align it with PIPEDA by eliminating the restriction that the Privacy Act applies to recorded

information only.

Background:

The definition of personal information under the Privacy Act is limited to

information that exists in recorded form. At the moment, personal information

contained in DNA and other biological samples is not explicitly covered. This

is not the case in the PIPEDA legislation – in which the definition of

personal information includes personal information in any form. New health

sector privacy laws in Canada also define personal information to include

unrecorded personal information. This broader, more modernized definition

serves as a means to protect the privacy rights of Canadians in a changing,

technology-driven world.

Rationale:

Having the Privacy Act Reflect Modern Realities

The Privacy Act’s current definition of personal information is outdated.

Unrecorded information, such as from surveillance cameras that monitor, but do

not record, individuals at border crossings and the comings and goings of

government workers is beyond the scope of the Privacy Act. In

an ever-shrinking world, it is important that individuals are free to go about

their daily activities anonymously. With the onset of rapid technological

changes, governments are using increasingly sophisticated means to monitor

Canadians in the work place and on the streets.

Likewise, personal information such as DNA and other human tissue samples are not covered.

This use of unrecorded information can yield intelligible information about

identifiable individuals. As such, it should have legal protection.

Harmonizing the Definition of Personal Information

Modern privacy laws such as PIPEDA and provincial private

sector privacy laws apply to both recorded and unrecorded information. For

example, a security company in the Northwest Territories mounted four security

cameras on the roof of its building aimed at a main intersection in Yellowknife. For several days,

24 hours a day, staff monitored a live feed and reported a

number of incidents to local police. The monitoring was intended to demonstrate

the service and generate business for the company.

Although a public outcry quickly ended the company’s video surveillance demonstration,

the OPC had the power to investigate under PIPEDA and issued findings that provided helpful

guidance for other organizations. The OPC concluded that, while monitoring public

places may be appropriate for public safety reasons, there must be a

demonstrable need, the monitoring must be done by lawful public authorities and

it must be carried out in ways that incorporate all legal privacy safeguards.

The Privacy

Act would not have permitted an investigation in this situation,

since no video recordings were made. A reformed Privacy Act needs to be

responsive to the digital imagery and biometric applications of contemporary

law enforcement surveillance and monitoring activities.

Strengthen the annual reporting requirements of government

departments and agencies under section 72 of the Privacy Act, by

requiring these institutions to report to Parliament on a broader spectrum of

privacy-related activities.

Background:

The Treasury Board Secretariat issued privacy reporting guidelines for government

institutions in April 2005, and updated these in February 2008.[8] The guidelines

buttress section 72 by requiring Deputy Heads to report comprehensively on a

wide range of management matters related to privacy promotion and protection

within federal institutions.

Rationale:

The Need for More Substantive Information

Our experience in reviewing section 72 reports over the years indicates that on the

whole they have rarely contained substantive information. As such their use to

Parliament, Canadians, and the OPC has been somewhat limited. Section 72

reports have tended to be a patchwork of statistics pertaining to the number of

requests received under the Privacy Act, the dispositions taken on

completed requests, the exemptions invoked or exclusions cited, and completion

times.

Integrating Into Law TBS Guidelines

The OPC is of the view that the Privacy Act should be amended by integrating

into the legislation requirements already provided for under the Treasury Board

guidelines. These guidelines are quite comprehensive, and among other things

require government institutions to provide:

-

a description of each PIA completed during the reporting period;

-

an indication of the number of new data matching and data sharing activities

undertaken;

-

a description of privacy-related education and training activities initiated;

-

a summary of significant changes to organizational structure, programs,

operations, or policies that may impact on privacy;

-

an overview of new and/or revised privacy related policies and procedures

implemented;

-

a description of major changes implemented as a result of concerns or issues

raised by the OPC or the Auditor General;

-

an indication of privacy complaints or investigations processed and a summary of

related key issues, and;

-

an indication of the number of applications or appeals submitted to the Federal

Court or Federal Court of Appeal on Privacy Act matters.

Benefits to Parliament, the OPC and Canadians

The Treasury Board guidelines would have added weight and authority if their

provisions were mandated by the Privacy Act. Parliamentary committees

would be better positioned to discharge their responsibilities to review the

personal information management practices of the federal government in the

broader context of reviewing departmental performance. A more comprehensive coverage

of privacy management issues would provide Parliamentarians with relevant

information to evaluate the extent to which government institutions are

addressing new and emerging privacy challenges, and whether programs or

initiatives being undertaken may pose a threat to the privacy rights of

citizens. Canadians too would be better informed on how their personal

information is being handled by government departments and agencies, and the

manner in which their information requests or complaints are being processed.

The OPC could better carry out its mandate, for the benefit of Parliament and

Canadians as a whole.

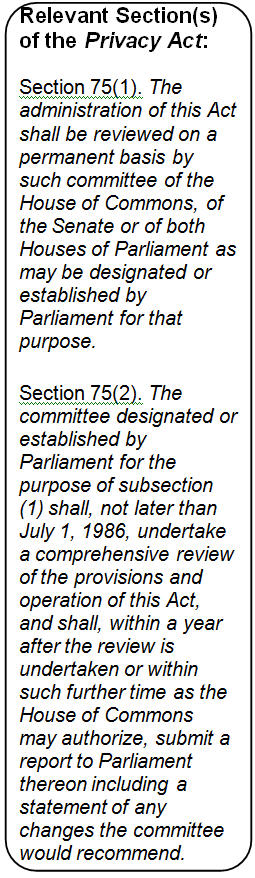

Introduction of a provision requiring an ongoing five year

Parliamentary review of the Privacy Act.

Background:

Currently, there is no mandatory periodic review of the Privacy Act to ensure its

ongoing evolution and adaptation to modern realities and challenges. By

contrast, section 29 of PIPEDA requires that the first part of that act

be reviewed every five years by the committee of the House of

Commons, or of both Houses of Parliament, that may be designated or established

by Parliament for that purpose. A number of provinces have a similar

requirement for regular legislative review of their public sector privacy law.

While a statutory review of the Privacy Act took place in 1987, the

recommendations in the report Open and Shut and in the testimony heard by the

Justice standing committee were never enacted.[9]

The OPC has repeatedly emphasized the need for informed public debate on

privacy laws whether they apply to the operations of government or to the

activities of the private sector. Discussion of privacy issues has been spotty

and targeted since the review in 1987, with a very limited consultation on

electronic commerce issues prior to PIPEDA implementation, and the sole Senate

committee hearings on the proposed privacy charter under Senator Sheila

Finestone in 1995-96.[10]

Rationale:

Harmonize the Data Protection Framework across

Jurisdictions in Canada

Harmonization between private sector and public sector laws at the federal level, and between

federal and provincial legislation, is a laudable goal for the privacy

protection regime in Canada wherever possible. Committing government officials

to a regular review of the legislation would greatly assist in that regard, as

developments at various levels of government could be more easily taken into

account.

Ensure the Privacy Act Keeps Pace with Rapidly

Evolving Technologies and International Trends

The Privacy Act serves as the information crux between Canadians and their

government; but as with previous reviews, there is a real risk of this

legislation fading into irrelevance as new programs, technologies and data

practices go unmonitored. A serious, sustained national discussion is now

needed to renew the Privacy Act for the networked, digital environment

that now exists in Canada. Cyberspace was the stuff of science fiction when

the Privacy Act came into force twenty-five years ago; today the

Internet and digital devices shape our identities, professional lives and

personal sphere in new ways every day.

In summary, the five-year review requirement would serve three ends. It would

help synchronize the Canadian data protection framework across jurisdictions;

keep the privacy practices of all organizations, both private and public

sector, on the minds of Canadian decision-makers and industry; and it would

ensure federal law keeps pace with rapidly evolving technologies and

international trends.

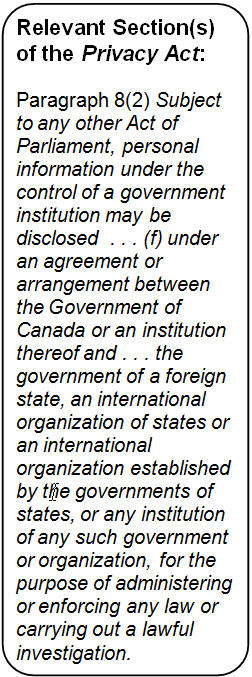

Strengthen the provisions governing the disclosure of personal

information by the Canadian government to foreign states.

Background:

Technological advances over the past two decades have made it much easier and cheaper for

governments to collect and retain personal information about their citizens.

At the same time, information sharing between nations has increased

dramatically as governments have adopted more coordinated approaches to

regulating the movement of goods and people and to combating transnational

crimes and international terrorism. In particular, enhanced information sharing has been a key strategy in improving

intelligence analysis since September 2001.

To cite a few examples: the Canadian Border Services Agency shares customs information and

information about travellers entering Canada; the Financial Transaction and

Reports Analysis Centre (“FINTRAC”) has over 40 agreements with other financial

intelligence units to shares information about individuals suspected of

engaging in money laundering or terrorist financing; Canada has negotiated Mutual

Legal Assistance Treaties (MLATs) with several countries; and law enforcement

and national security agencies regularly share information with international

counterparts.

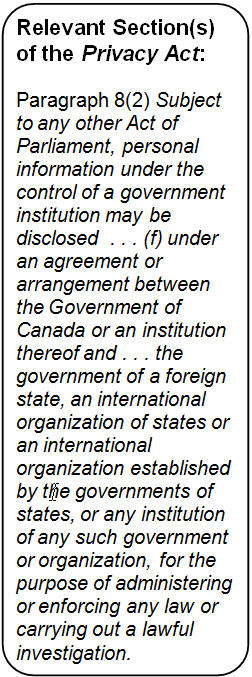

However, the Privacy Act does not reflect this increase in international information sharing.

The Privacy Act places only two restrictions on disclosures to foreign

governments: an agreement or arrangement must exist; and the personal

information must be used for administering or enforcing a law or conducting an

investigation. The Privacy Act does not even require that the agreement

or arrangement be in writing. The Privacy Act does not

impose any duty on the disclosing institution to identify the precise purpose

for which the data will be disclosed and limit its subsequent use by the

foreign government to that purpose, limit the amount of personal information

disclosed and restrict further disclosure to third parties. Moreover, the Privacy

Act even fails to impose any basic obligations on the Canadian government

institution itself to adequately safeguard personal information.

As reported in the OPC’S 2002-2003 Annual Report, the Office conducted a

preliminary review of 21 information-sharing agreements between Canada and the US.

It concluded that only about one-third were reasonably well drafted. To mention

just two deficiencies: many of the agreements did not describe the personal

information to be shared or include a third party caveat; that is, a statement

indicating that the information received under the agreement will not be

disclosed to a third party without the prior written consent of the party that

provided the information.

Rationale:

Putting in Place Standards for the Sharing of Personal

Information

The consequences of sharing personal information without adequate controls

are clearly demonstrated in Justice O’Connor’s Report on the Factual Inquiry

with respect to the Commission of Inquiry into the Actions of Canadian Officials in

Relation to Maher Arar. Justice

O’Connor concluded that it was very likely that, in making the decisions to

detain and remove Mr. Arar to Syria, the U.S. authorities relied on inaccurate

information about Mr. Arar provided by the RCMP.

The lack of standards governing the sharing of personal

information by Canadian officials was also addressed in a January 2008 public

hearing as part of work currently being conducted by former Supreme Court of

Canada Justice Iacobucci, in the Internal

inquiry into the actions of Canadian officials in relation to Abdullah Almalki,

Ahmad Abou-Elmaati and Muayyed Nureddin.

Minimizing Risks to Canadians by Clearly Defining

Responsibilities

In order to minimize the risks to Canadians resulting from this

increased information sharing, the OPC believes that the Government of Canada

and Parliament should consider specific provisions to define the responsibilities

of those who transfer personal information to other jurisdictions and to

address the issue of the adequacy of protection in those jurisdictions.

Prescribing the Form and Content of Information-Sharing

Agreements

The Treasury Board Secretariat has developed guidelines setting out elements

that a written agreement or arrangement should

contain. These guidelines are a positive first step that should be formalized

either in legislation or by amending section 77 of

the Privacy Act to include a provision allowing the Governor-in-Council

to make regulations prescribing the form and content of information-sharing

agreements.

Limiting Disclosure of Personal information

In addition, paragraph 8(2)(f) should be amended to state that personal

information may only be disclosed where the information is required for the

purpose of administering or enforcing any law which has a reasonable and direct

connection to the original purpose for which the information was obtained.

A Chronology of Recommendations

Theme

|

Open and Shut: Enhancing the Right to Know and

the Right to Privacy

Report of the Standing Committee of Justice and Solicitor General on the

Review of the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act (March

1987) |

The Steps Ahead:

Government Response to Open and Shut: Enhancing the Right to Know and the

Right to Privacy (1987) |

Government Accountability for Personal Information

- Reforming the Privacy Act (June 2006) |

Addendum to Government Accountability for Personal

Information: Reforming the Privacy Act (April 2008)

&

Opening Statement by Jennifer Stoddart, Privacy Commissioner of Canada on Privacy Act Reform (April 2008) |

1. Limiting Collection |

|

|

Amend Privacy Act to include a "necessity test" for the collection

of personal information.

Amend Privacy Act to strengthen notice requirements to individuals.

|

Amend Privacy Act to include a "necessity

test" for the collection of personal information. |

2. Expanding Court Review |

Simplify

rules of court to allow individuals to seek court review in as simple a

manner as possible and that Federal Court should award costs on

solicitor-client basis to a successful applicant.

Amendment to provide individuals with monetary damages for identifiable harm

resulting from unauthorized collection, improper disclosure and denial of

access.

|

No

direct response with respect to simplifying rules of court.

Creation of civil sanctions in Privacy Act not warranted at this time.

|

Amend

the Privacy Act to permit Court review of innapropriate collection,

use, disclosure of personal information.

Amend Act to give Court the power to award damages.

|

Amend the Privacy Act to permit Court review of

innapropriate collection, use, disclosure of personal information.

Amend Act to give Court the power to award damages.

|

3. Privacy Impact Assessments |

Privacy

Impact statement requirement for all legislation before Parliament with

privacy implications. |

Government

will not move to require that a PIA accompany each piece of legislation. |

Amend Privacy Act to require PIAs and public reporting on results of PIAs. |

Amend Privacy Act to require PIAs and

public reporting on results of PIAs. |

4. Research and Public Education Mandate |

Amend Privacy Act to include public education mandate for Treasury Board and

Privacy Commissioner.

Amend Privacy Act to enable Privacy Commissioner to undertake research

studies.

|

Government

will establish public awareness program.

Government will amend Privacy Act to include public education mandate

for Privacy Commissioner.

No direct response with respect to research mandate.

Government

recognized Privacy Commissioner should have public education mandate. |

Amend Privacy Act to give Privacy Commissioner research and education

mandate. |

Amend Privacy Act to give Privacy Commissioner

research and education mandate. |

5.

Communication with Public |

|

|

Amend

the Privacy Act to enable the Privacy Commissioner to disclose

information on the privacy management practices of government institutions

outside the Annual Reporting vehicle. |

Amend the Privacy Act to enable the Privacy

Commissioner to disclose information on the privacy management practices of

government institutions outside the Annual Reporting vehicle. |

6. Discretion in Dealing with Complaints |

|

|

Amend

the Privacy Act to give the Privacy Commissioner the discretion to

more efficiently and expeditiously deal with complaints which have less

systemic and societal significance. |

Amend the Privacy Act to give the Privacy

Commissioner the discretion to more efficiently and expeditiously deal with

complaints which have less systemic and societal significance. |

7. Definition of "Personal Information" |

Amend

definition of "personal information" to include personal data in

any form. |

Maintain

definition, monitor government surveillance and testing activities. |

Amend

definition of "personal information" to include unrecorded

information. |

Amend definition of "personal

information" to include unrecorded information. |

8. Annual Reporting Requirements |

Establish

hearings to review annual reports of institutions under section 72 of the Privacy

Act.

Amend section 72 of Privacy Act to require TBS to prepare a

Consolidated Annual Report on annual reports received from government

institutions. |

No

direct response.

Government will prepare the consolidated annual report for 1987-1988 fiscal

year. |

Amend

section 72 of the Privacy Act to strengthen annual reporting

requirements for government institutions. |

Amend section 72 of the Privacy Act to

strengthen annual reporting requirements for government institutions. |

9. Public Consultation/ Review of Act |

Amend

section 75(2) of the Privacy Act to provide for a second legislative

review four years after tabling of Open and Shut. |

Government

supports ongoing parliamentary oversight, however, Committee should set its

own agenda. |

Need

for broad based public consultation. |

Introduction of a provision in the Privacy Act requiring

an ongoing five-year parliamentary review of the Act. |

10. Transborder Data Flows |

No

Amendment to Privacy Act recommended, but Government should conduct a

review/study of TBDF. |

Government

agreed. |

Amend

paragraph 8(2)(f) of the Privacy Act to tighten control over

information sharing with foreign states.

Amend section 77 of the Privacy Act to add regulation making power

regarding information sharing agreements.

|

Amend paragraph 8(2)(f) of the Privacy Act to tighten control over information sharing with foreign states.

Amend section 77 of the Privacy Act to add regulation making power

regarding information sharing agreements.

|

|