INDU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

| |

|

|

|

|

The Government of Canada has not developed a services sector-specific industrial policy, but through various programs supports both the goods sector and the services sector in Canada. One overarching services sector issue raised by many witnesses was the general unavailability of data, at least insufficient data for the needs of the sector’s analysts. Effective data collection and dissemination are essential for government, individuals and enterprises in the public and private sector to make evidence-based decisions. Although data is collected and analyzed across a range of service industries, more data on the services sector as a whole is needed to enhance understanding and allow for greater analysis of the sector. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada continue to improve Statistics Canada’s collection and dissemination of data on the services sector. The Committee also found that often overlooked in the services sector is the contributions made by the co-operative movement. Canada’s economy includes more than 9,000 cooperatives, with more than 170,000 employees and total assets of over $260 billion. Indeed, 13 million Canadians, or 40% of the population, are members of a co-operative. Canada’s co-operatives are found in many services sub-sectors such as financial services, retail, housing, daycare, recreational facilities, electricity and water supply. Despite this diversity of business activities, the federal government provides oversight of co-operatives through its Co-operatives Secretariat, which has been organized within Agriculture Canada since it was established in 1987. The Committee questioned the placement of the Secretariat within Agriculture Canada, given the strong engagement of the movement in the services sector. Indeed, representatives of co-operatives were the first to question this organizational structure, as they believe that it does not accurately reflect the diversified nature of the co-operative movement. They suggested moving the Co-operatives Secretariat to Industry Canada. The Committee agrees. Although the Committee recognizes the historical dominance of agricultural cooperatives within the co-operatives movement in Canada, it believes that the Secretariat’s placement within Agriculture Canada does not reflect the diversified character of co-operatives in Canada. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada move the responsibility for the Co-operatives Secretariat from Agriculture Canada to Industry Canada. Over the past decade, three main factors have shaped Canada’s workforce: (1) an increasing demand for skills in the face of advanced technologies and the high pace of growth of the “knowledge based economy”; (2) a working-age population that is increasingly made up of older people; and (3) a growing reliance on immigration as a source of skilled labour. Added to this mix of long-term trends is a recent structural development that is forcing a reallocation of labour, both from one sector of the economy to another (i.e., from the manufacturing sector to other goods-producing sectors and the services sector), and from one region of the country to another (from eastern and central Canada to western Canada). Table 1

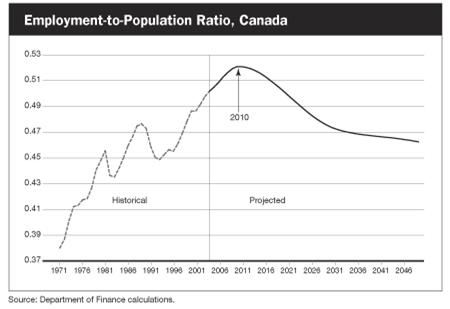

Source: Statistics Canada, Canada’s Changing Labour Force, 2006 Census, p. 25. Data from the 2006 Census indicate that the number of people in the labour force increased by 1.3 million between 2001 and 2006. The data also show that Canada’s workforce is aging: those aged 55 and older accounted for 15.3% of the total labour force in 2006, up from 11.7% in 2001. The median age of the labour force was above 40 years for the first time ever: the median age was 41.2 years in 2006, up from 39.5 years in 2001. 11 Occupations such as farmers, real estate agents, property administrators, bus drivers, ministers of religion, and senior managers in the private and public sectors have particularly high median ages (see Table 1). Many of these occupations are found in the services sector. The combination of an aging population, a lower retirement age, fewer young people entering the working-age population, increased demand for workers with specialized skills, and international worker mobility has led (or may lead) to labour shortages in some areas of the economy. 12 Moreover, Finance Canada expects Canada’s employment-to-population ratio to turn negative in 2010, as growing numbers of “baby boomers” retire (see Figure 18). 13Somewhat in response, Canada has increasingly turned to immigration as a source of skilled labour. Data from the 2006 Census indicate that about 3.6 million individuals in the labour force were foreign born. Foreign-born individuals thus account for more than one-fifth (21.2%) of Canada’s total labour force of about 17.1 million people in 2006, up from 19.9% in 2001. 14 Figure 18

The rapid and significant appreciation in the value of the Canadian dollar since 2002 has made many manufacturers less competitive relative to foreign competitors. They have had to both reduce employment and invest in capital machinery and equipment to raise their labour productivity levels in order to stabilize their production levels and relative competitiveness. Given that national employment levels have risen to all-time highs and national unemployment rates have declined to modern day lows (i.e., lowest levels in 33 years), other goods-producing sectors and services sectors are engaging many of the skilled workers laid-off by the manufacturing sector. In part because of this uneven economic performance across major sectors of the economy, employment growth has been uneven across the country. National employment averaged 16 million in 2006, up 1.3 million from 2001. Two provinces — Alberta and British Columbia — accounted for about one third of this increase. Moreover, the unevenness of employment growth across the country also stimulated considerable migration. According censuses data, 562,800 employed people or 3.4% of the labour force moved to a different province or territory between 2001 and 2006. The three northern territories, followed by Alberta, had the highest shares of people from another province making up their labour force. Focusing on Canada’s services sector, employment approached 12.9 million in 2007, and has grown on average by 2.4% per annum between 2002 and 2007, accounting for almost 93% of the increase in total employment in Canada between 2002 and 2007. Many industries across the services sector report current or anticipated difficulties in hiring and retaining staff. Indeed, such problems are likely to become more pronounced as demographic changes lead to a shrinking labour force. The Committee recognizes that slower economic growth induced by a labour skills shortage can be mitigated or countered by taking actions to: (1) increase the participation rate of those not fully participating in the labour force; (2) increase the value of work performed per person of those already in the labour market; and/or (3) increase the skill levels of those entering the labour force. In the hope of reducing some of the barriers to re-entering the labour market by selected groups who have either completely or partially withdrawn from the labour market, most notably low-income individuals and seniors, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada continue reforming fiscal policies that discourage work by:

Other notable groups who are not fully participating in the labour force include new parents. Child care for children aged six months to five years is utilized by most Canadian parents, and use rates are increasing. In 2003, 52% of children from two-parent households and 64.4% of children in single parent households were cared for by someone other than a family member, an increase from 42% and 39%, respectively, from 1995. 15 Rates of daycare use varied by province: Alberta being the lowest (46%) and Quebec being the highest (70%). Cost to parents also varies by province from an average of $205 per month in Quebec to $800 in Ontario. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada work with the provincial and territorial governments to implement early childcare and early learning systems with the aim of reducing barriers to parents, particularly women, who choose to be in the workforce. In the hope of increasing the value of work performed per person of those already in the labour market, the Committee first focuses on the plight of recent immigrants to Canada. It is far too often the case that immigrants to Canada may have professional qualifications, for example in the healthcare, engineering, or education fields, but the time taken to recognize their foreign credentials may delay by a considerable length of time their right to begin work in their chosen profession in Canada. This situation leaves Canada at a disadvantage when highly qualified professionals are in short supply. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and professional organizations to streamline the entry of foreign workers into the labour force, with the goal to commence, and if possible to complete, the process of recognition of foreign credentials in the country of origin. The Committee now focuses on other existing labour market participants who could raise their skill levels and assist in reducing any impending skills shortage. The reallocation of labour necessitated by industrial restructuring and a relatively high-valued Canadian dollar has, in some cases, been insufficient in terms of the number of potential employees available or in matching skill sets with demand, and has prohibited some companies and industries from meeting rising demand for their services. Improving employee skills through on-site training or by sending employees to training programs are ways for firms to deal with a lack of skilled labour. Employees with enhanced skills not only help the company providing the training, but they are more marketable in the long term, and less likely to draw Employment Insurance, or to draw it for shorter periods of time, in the future. The cost of paying for training and temporarily losing employees while they are participating in training activities often prohibits companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, from providing training to their employees. Furthermore, since employees that have upgraded their skills are more marketable, they may seek other, more lucrative employment opportunities, especially in tight labour markets, once their training is complete; the company providing the training may therefore reap little or no benefit from the training for which it has paid. To address this problem, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada provide tax credits and/or other measures to companies providing employer-financed training and apprenticeships to their employees. Tax relief in various forms was suggested by most witnesses and was not limited in its application to the services sector. The suggested tax measures were most often meant to address their existing or impending labour shortage problems and skills development shortcomings. These issues were addressed by the Committee in the preceding section. By far the next most controversial tax issue mentioned by witnesses stemmed from inefficiencies resulting from two sales tax regimes (federal versus provincial). Some witnesses suggested further reductions in corporate income tax rates as a means of spurring economic activity. Finally, one witness suggested the introduction of income averaging provisions to the federal income tax system to provide tax relief for individuals with highly variable incomes. Beginning with Canada’s income tax regime and the cultural industry’s call for an income averaging provision — possibly similar to that which prevailed in the 1970s — the Committee looks first to the issue of equity, followed by fiscal or budgetary issues. Canada’s federal income tax system imposes higher tax rates on annual income that falls within higher income tax brackets. For many, the progressive structure of Canada’s income tax system ensures a fair distribution of the tax burden according to one’s ability to pay, thereby satisfying so-called “vertical equity” concerns. One unintended consequence of a progressive tax system that is based on annual income, however, is that an individual with variable annual income may end up paying more taxes than an individual with stable income even though the two individuals earn the same income over a period of several years. In this case, the principle that people earning the same level of income should face the same tax burden is violated because the income tax system is based on annual income, and the choice of “annual income” over daily, weekly, monthly, biennial or triennial income is simply a matter of convention and convenience. Convention, convenience and “vertical equity” concerns thus appear to trump “horizontal equity” concerns in the case of variable annual incomes under Canada’s current progressive annual income tax system. In 1973, the Income Tax Act introduced a general averaging provision that was made available to taxpayers whose income in a particular taxation year was 10% higher than their prior year’s income and 20% higher than the average of their annual income for the four preceding years. 16 This general averaging provision was eliminated in 1982 and was replaced with a forward income-averaging mechanism available to all taxpayers, only to see it gradually phased-out starting in 1988. The Department of Finance estimated that the general averaging provision cost the federal government $350 million in foregone revenue for the 1980 calendar year. 17 When adjusted for inflation and the number of tax returns, this cost estimate would be approximately $1.5 billion in foregone revenue for the federal government for the 2006 calendar year. The Committee believes that Canada’s tax regime must provide equity to individuals with variable incomes through similar treatment to individuals with stable incomes and, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada introduce measures into the income tax system that would allow self-employed Canadians with highly variable incomes to average their incomes over several years. The Committee also agrees with the witnesses who suggested further reductions in corporate income tax rates as a means of spurring economic activity and productivity growth. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada continue to reduce the federal corporate tax rate. Moving on to Canada’s Goods and Services Tax (GST), many witnesses suggested that the government should: (1) harmonize the GST with provincial retail sales taxes; (2) reinstate the GST rebate for foreign visitors; and (3) remove the GST from books. The rationale for reinstating the former rebate on the GST for foreign visitors is to provide indirect financial assistance to the tourism industry that has been particularly hit hard by the large and rapid ascent of the Canadian dollar, high fuel prices, lengthy wait times at the border, confusion surrounding passport requirements and a relative shift towards more exotic holiday destinations. Canada has seen a decrease in international tourists from 40.9 million in 2003 to 28.9 million in 2006. Consequently, Canada’s tourism trade deficit has grown from $1.7 billion in 2002 to $7.2 billion in 2006 and is expected to be more than $8 billion in 2007. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada reinstate the Goods and Services Tax (GST) rebate for foreign visitors and promote this rebate to visitors upon entry into Canada. Finally, the rationale for removing the GST on books is to reduce financial barriers to literacy. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada remove the Goods and Services Tax (GST) on books. Innovation, Intellectual Property and Technology Policies Innovation often underlies the ability of Canada’s services sector to grow and compete internationally. Whether it is new processes resulting from intensive research and development, enhanced training or education, data storage, improved regulations or deregulation, or a new design and marketing strategy, innovation makes services sector firms a better place to work, more effective in providing services to Canadians, and more competitive against foreign rivals. In order to remain at the cutting edge of developing and implementing services sector innovations, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada develop a services sector innovation strategy. The Committee understands that business R&D intensity (expenditure relative to industry’s contribution to GDP) in Canada is lower than the OECD average, and that the business sector funds and performs a lower percentage of R&D to total national R&D than does the business sector of other OECD countries. Consequently, the Government of Canada supports industrial research and development (R&D) in a number of ways, including the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program. Canada’s SR&ED program is one of the most advantageous in the industrialized world, providing more than $2.6 billion in deductions or credits to Canadian businesses in 2005. The tax incentives for SR&ED come in two forms: (1) income tax deductions; and (2) investment tax credits (ITCs) for SR&ED conducted in Canada. In terms of income tax deductions, current expenditures (e.g., salaries of employees directly engaged in SR&ED, the cost of materials consumed in SR&ED, overhead) and capital expenditures on machinery and equipment are fully deductible in the year incurred. Unused deductions may be carried forward indefinitely. In terms of ITCs, there are two rates under SR&ED:

ITCs may be deducted from federal taxes otherwise payable. Unused ITCs may be carried back three years or carried forward 20 years. The Committee deliberated on a number of suggestions for change to the SR&ED tax incentive program, including:

Finance Canada concludes that the cost of extending full refundability of SR&ED ITCs to all firms and all types of expenditures would depend on the treatment of existing pools and unused ITCs. Depending on whether the application of ITC pools to current taxes would affect the refund available, the fiscal cost of refundability is estimated to be between $5 billion and $10 billion over five years. Finance Canada concludes that the cost of excluding SR&ED ITCs from the tax base would depend on whether the proposal would apply only to federal ITCs, or include provincial ITCs for R&D, and whether the change in allowable expenditures for the purpose of the tax deduction would also flow through to qualified expenditures for the ITCs. Depending on how the change is implemented, the fiscal cost is estimated to be between $1 billion and $4 billion over five years. Finance Canada concludes that the cost of providing an allowance for international collaborative R&D would depend on the definition of this activity and the type of allowance provided. Based on Statistics Canada data on industrial payments for R&D and other technical services abroad, and assuming the allowance would be provided by including expenditures for such activities in the base for the ITC, the fiscal cost of this proposal is estimated to be $2.2 billion over five years. Finance Canada did not provide an estimate on extending the tax credit to cover patenting, prototyping, product testing, and other pre-commercialization activities because there was no data readily available on the size of corporate expenditures on these items. Therefore, excluding the proposal to extend the tax credit to cover these other activities, the fiscal cost of implementing the above SR&ED measures would vary from $8.2 billion to $16.2 billion over five years. However, given the extent of the fiscal costs and the as-of-yet non-quantified social and fiscal benefits associated with the above suggested changes, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada improve the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program to make it more accessible and relevant to Canadian businesses. The Committee made a similar recommendation in its previous report dealing with the manufacturing sector, entitled Manufacturing: Moving Forward — Rising to the Challenge, 18 and was given a positive response by the government. 19 The Committee, therefore, awaits the government’s final conclusions and decision on potential changes to the SR&ED tax incentive program. Critical support for some innovations — often the result of R&D — is provided by intellectual property law. Intellectual property laws confer a bundle of exclusive rights upon authors and inventors for a limited period, allowing them to better exploit their works and invention. The rationale for the creation of such rights is that they facilitate and encourage the pursuit of innovation (i.e., increase the profitability associated with innovation by discouraging unauthorized copies from entering the marketplace and competing with the original) and the disclosure of knowledge into the public domain for the common good (i.e., thereby reducing secrecy as a profit-making strategy and permitting others to improve upon the innovation). The intellectual property (IP) right is the only industrial tool that rewards the innovator commensurate with the innovation’s commercial prospects. In Canada, the following federal laws and regulations, which are administered by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office (with the exception of the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act), relate to the protection of IP: 20

In terms of controlling counterfeiting and piracy specifically, other pertinent federal legislation includes the Food and Drugs Act, the Customs Act, the Canada Border Services Agency Act and the Criminal Code. Counterfeiting and piracy affect the services industry in many ways, including the loss in sales in the retail sector of the legitimate product, loss of revenues in entertainment through film piracy, and lower levels of research and development. In particular, the Committee heard that in some cases (e.g., Microsoft products) levels of software piracy are above 33%. The Committee views trademark counterfeiting and copyright piracy as a drain on the Canadian economy, and, in the case of some counterfeit goods, as a threat to public health and safety. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada vigorously enforce intellectual property, anti-counterfeiting and anti-piracy legislation. Access to the latest information technology can give small businesses across the services sector an advantage. Whether used for inventory control in the retail sector, communications in the financial and insurance sector, research and development, the latest publishing or editing tools, or other industries, information technology can increase productivity and reduce costs. However, investments in information technology can be expensive and their payback periods may be long. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada introduce an information technology investment tax credit for small businesses. Unimpeded labour mobility is an important component of an efficient labour market. The Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT), signed in 1994, requires that provinces and territories eliminate barriers to labour mobility such as residency requirements for registration and unnecessary fees and delays. It also requires governments to mutually recognize the qualifications of workers already qualified in other provinces/territories, reconcile differences in occupational standards, and put in place accommodation mechanisms to help workers acquire any additional competencies they need related to differences in scope of practice across jurisdictions. Despite this agreement, there continue to be inter-provincial barriers to labour mobility; progress is being made in removing these barriers but it has been slow. In September 2006, the Committee of Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Internal Trade came to an agreement on an action plan on internal trade. A key component of the action plan is a strategy to improve labour mobility so that by April 1, 2009, Canadians will be able to work anywhere in Canada without restrictions on labour mobility (i.e., full compliance with the labour mobility provisions of the AIT). The Committee supports: Agreements recently concluded on construction labour mobility between Quebec and Ontario and on trade, investment and labour mobility signed by Alberta and British Columbia. The Committee believes that removing all additional barriers to labour mobility within Canada is an important means of dealing with regional shortages of skilled labour and ultimately leads to a better allocation of labour within the country. The Committee also intends to undertake a study of these inter-provincial barriers in the near future, but until such time the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada should take a leadership role and encourage the provinces to bring down inter-provincial trade, investment and labour mobility barriers. Governments use regulation in combination with other instruments, such as taxation, program delivery and services, and voluntary standards to achieve public policy objectives. Regulations can be beneficial to businesses by creating an environment in which commercial transactions take place in predictable ways, consistent with the rule of law. Complying with regulations can, however, be a costly endeavour, and hits small businesses particularly hard. The Committee believes that, in certain cases, regulation is excessive or duplicative, and that in these cases, regulation is impeding innovation or productivity. One such example was provided to the Committee by representatives of the retail sector involving the movement of foreign-based marine containers. Unlike in the United States, Canadian regulations (i.e., Customs Tariff 9801.10.00) require incoming (foreign-based) marine containers to exit via the same port within 30 days, and they must return empty rather than be refilled in order to ensure duty-free treatment. The Committee is unsure of the social objectives that these rules are meant to achieve, but understands very clearly both the added costs imposed on retailers from adopting regulations that breed inefficient transportation and distribution methods, as well as their adverse environmental implications. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada study and review regulations that govern the movement of marine containers (i.e., cabotage regulations) such as the requirement that incoming containers exit via the same port within 30 days. The services sector needs access to modern infrastructure to allow the continued growth of the sector. This includes transportation, water and sewage, and telecommunications infrastructure. The retail, food and restaurant sectors depend on transportation infrastructure to ship goods. The travel and tourism industries depend on transportation infrastructure. The information technology and the financial services industries rely on an effective telecommunications infrastructure, and the Committee heard from the insurance industry on the need to renew water and sewage infrastructure to minimize the risk of catastrophic flood events. As such, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada increase efforts in partnership with the provinces and municipalities to invest in transportation, water and sewage infrastructure. A border or immigration official is often the first Canadian a visitor to Canada will speak with on their arrival in the country, and his or her demeanour provides a first, and sometimes lasting, impression of Canada. The Committee recognizes the professionalism of border and immigration officials, their role in protecting the Canadian public, and the need for them to maintain vigilance at all times. Whilst carrying out those duties, border and immigration official have a unique opportunity to give visitors a positive first impression of Canada, enhancing the visitors experience, as well as welcoming back returning Canadians. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada encourage border and immigration officials to be welcoming to people entering Canada. Canada’s business sector — most notably, the tourism industry — is particularly concerned about continued delays at certain border crossings into the United States. The Windsor-Detroit Corridor is Canada’s most important entry to the United States, with 28% of goods shipments between Canada and the United States passing through that corridor. Congestion at this crossing has a negative impact on Canada’s economy. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada continue to invest substantially in infrastructure to reduce delays at Canada-U.S. border crossings and all points of entry, and ensure new passport rules are implemented seamlessly. Although services make up three quarters of domestic commercial activity, they account for a much smaller proportion of international trade. In 2007, services accounted for only 13% of exports and 17% of imports. The Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, through its Trade Commissioner Service at foreign missions, promotes and facilitates trade between Canada and international partners. In order to fully exploit opportunities to enhance international trade in the services sector, the Committee recommends: That the Government of Canada continue to ensure that staff in foreign missions has the expertise, knowledge and resources to promote the services sector. As a trading nation, Canada remains committed to multilateral trade and its rules-based system that underpins commercial relations with the 148 other member countries of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Canada’s first priority on matters of trade continues to be the enhancement of the multilateral trade system, including the conclusion of an agreement based on the “Doha Development Agenda” launched in November 2001. As part of its prosperity initiative, Canada has also negotiated a bilateral free trade agreement with Chile, Costa Rica, Israel and the United States and a regional free trade agreement with Mexico and the United States. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada seek further favourable and comprehensive bilateral and multilateral trade agreements that would include services sector obligations. As established in its November 2006 policy statement, entitled Blue Sky: Canada’s International Air Policy, the Government of Canada will proactively pursue opportunities to negotiate more liberalized agreements for international scheduled air transportation that will provide maximum opportunity for passenger and all-cargo services to be added according to market forces. More specifically, Canada will seek to negotiate reciprocal “Open Skies”-type agreements similar to the one negotiated with the United States in November 2005, where it is deemed to be in Canada’s overall interest. According to the Government of Canada, an “Open Skies”-type agreement would cover the following elements for scheduled passenger and all-cargo services:

Under no circumstances will the policy approach include cabotage rights — the right for a foreign airline to carry domestic traffic between points in Canada (eighth and ninth freedom rights). The Committee agrees and, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada pursue more open skies agreements to the benefit of Canadians. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) has established a quota system to regulate the amount of Canadian content (also known as Cancon) on radio, television and specialty broadcasting based on its mandate provided under the Broadcasting Act which stipulates that: 21 The Canadian broadcasting system should:

Requirements for Canadian content vary by broadcast medium: 35% of music on commercial radio stations must be Canadian, and 60% of television shows must be Canadian. For music to qualify as Canadian content, it should be composed, written or performed by a Canadian, or should be performed or recorded in Canada. For television programming evaluation is made on the basis of whether creative personnel are Canadian, and the amounts paid to Canadian to produce the program. There are also guidelines under the Investment Canada Act governing Canadian content in magazines to ensure “the availability to Canadians of periodicals that are relevant to Canadian life and culture, reflect an identifiably Canadian perspective and meet the information needs of Canadian readers.” 22 In general, foreign investments in periodicals are reviewed to ensure there will be a majority of original Canadian content authored by Canadian writers, journalists, illustrators or photographers, or content created solely for the Canadian market. Telecommunications, cable-television and satellite television companies, by contrast, are governed by foreign ownership restrictions set out in the Telecommunications Act and the Broadcasting Act. Direct foreign ownership in such companies cannot exceed 20% of the share capital of the corporation. In addition, according to Canadian Telecommunications Common Carrier Ownership and Control Regulations, the minimum Canadian ownership level for ownership at the holding company level is 66⅔% of voting shares. This caps foreign ownership in a telecommunications common carrier and a broadcast distribution undertaking (BDU) at 46⅔%. 23 The Committee agrees with these restrictions and recommends: That the Government of Canada increase efforts to provide regulation that promote Canadian ownership and Canadian content in media. Inaccessibility to services was cited as the main challenge in health care services. In the publicly funded health care field, inaccessibility and long wait times are caused by too few health care professionals or lack of equipment. The Canadian Medical Association (CMA) estimates the cumulative cost of waiting for joint replacement, cataract surgery, heart bypass grafts and MRI scans is $14.8 billion. The CMA also estimates that almost 5 million Canadians do not have access to a family physician. Canada ranks twenty-fourth among OECD countries in terms of physicians-per-population ratio and would need 26,000 more doctors to meet the OECD average. In private care such as dentistry, problems with access are generally caused by high fees, with some Canadians unable to pay for the high cost of treatment and therefore going without care. The Canadian Healthcare Association made a number of interesting suggestions and this Committee finds itself in agreement with some of them. The Committee, therefore, recommends: That the Government of Canada ensure health care workers offering services to First Nations, Inuit and Métis people be appropriately culturally educated; and That the Government of Canada work with provincial and territorial governments to improve the retention of health care workers providing services to First Nations, Inuit and Métis. [11] Statistics Canada, Canada’s Changing Labour Force, 2006 Census. [12] Canada’s population is aging due to a prolonged period of low fertility and increasing life expectancy. Fertility in Canada has been declining since the 1960s; the fertility rate was 3.9 children per woman in 1956 and, currently, it stands at 1.7, which is significantly below the replacement rate of 2.1. Given this performance, births in Canada peaked in 1990, trending downward ever since. Canadians, on average, lived 80.1 years in 2005, up 11 years from 69.1 years in the 1950-1955 period. The source of the cited data is Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, Policy Research Initiative Project: Population Aging and Life-Course Flexibility, Encouraging Choice: Aging, Labour Supply and Older Workers, briefing note, November 2005. [13] Finance Canada, Budget 2005, Annex 3, Canada’s Demographic Challenge, p. 296-311. [14] Statistics Canada, Canada’s Changing Labour Force, 2006 Census, p. 29. [15] Statistics Canada, The Daily, Child care: An eight-year profile, 5 April 2006, http://www.statcan.ca/Daily/English/060405/d060405a.htm. [16] The general averaging provision was phased in, so the number of applicable preceding years was one year in 1973, two years in 1974 and three years in 1975. Furthermore, incomes for the purpose of the scheme could not fall bellow a certain threshold: $1,700 in 1973 and from then on was indexed to the cost of living. [17] Department of Finance, “Government of Canada Tax Expenditure Accounts,” December 1980. [18] House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry Science and Technology, Fifth Report, Manufacturing: Moving Forward – Rising to the Challenge, February 2007, /content/committee/391/indu/reports/rp2663393/indurp05/indurp02-e.pdf. [19] Department of Finance Canada, The Budget Plan 2007: Aspire to a Stronger, Safer, Better Canada, March 19, 2007, http://www.budget.gc.ca/2007/pdf/bp2007e.pdf. [20] Industry Canada, Intellectual Property Policy Directorate, Laws and Regulations, http://www.strategis.ic.gc.ca/epic/site/ippd-dppi.nsf/en/h_ip00007e.html. [21] Canadian Broadcasting Act, http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/ShowFullDoc/cs/B-9.01///en. [22] Heritage, Cultural Sector Investment Review, Canadian Content in Magazines: A Policy on Investment in the Periodical Publishing Sector, www.canadianheritage.gc.ca/progs/ac-ca/progs/eiic-csir/period_e.cfm (accessed December 5, 2007). [23] The 66⅔% minimum level for Canadian ownership means that a foreign company that holds 20% of the voting stock of a Canadian telephone operating company could also have a 33⅓% stake in a company that held the remaining 80% voting stock of the Canadian telephone operating company. Multiplying 33⅓% by 80% and adding 20% leads to the current aggregate direct and indirect foreign ownership limit of 46⅔%. |