LANG Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

1. CONTEXT OF THE STUDY

Before analyzing the testimony heard by the Committee, let us first look briefly at the demographic characteristics of Canada’s various official language communities (section 1.1), and describe the relatively complex environment in which initiatives under the Action Plan for Official Languages are taken. This environment comprises the constitutional framework which sets out the official languages responsibilities of the federal and provincial governments (section 1.2); federal legislation and related regulations which define the federal government’s specific official language responsibilities, the key item of course being the Official Languages Act of 1969, which was amended in 1988 to include support for the development of official language minority communities (section 1.3); a description of the Action Plan for Official Languages, highlighting the elements most likely to have a significant impact on the development of official language minority communities (section 1.4); and finally, what is known as the Official Languages Program, which includes all the programs that the Department of Canadian Heritage is responsible for delivering (section 1.5).

1.1 Profile of official language minority communities in Canada[4]

In 2001, there were 987,640 Francophones living outside Quebec, or 4.4% of Canada’s population less the population of Quebec; while Quebec’s Anglophone community had 918,955 members, or 12.9 % of Quebec’s total population.[5]

Minority Francophones communities are very diverse. They are sometimes concentrated in specific regions, such as northern New Brunswick, Eastern Ontario or urban areas such as the St. Boniface district of Winnipeg. They can also be highly dispersed, whether in urban areas such as Toronto or Vancouver or in the rural regions of Newfoundland and Labrador or Saskatchewan.

Quebec’s Anglophone community is highly concentrated in the Montreal area, with significant concentrations in the Eastern Townships, and smaller groups in Quebec City, the Outaouais and the Gaspé.

Official Language Minority Population by Province or

Territory

(Source: Statistics Canada, 2001 Census)

Province/Territory |

Official Language Minority |

Total Pop. |

|

Number |

% |

||

Nwfld. and Labr. |

2 100 |

0.4 |

508 075 |

Pr. Ed. Island |

5 275 |

4.0 |

133 385 |

Nova Scotia |

33 765 |

3.8 |

897 570 |

New Brunswick |

238 450 |

33.1 |

719 710 |

Quebec |

918 955 |

12.9 |

7 125 580 |

Ontario |

527 710 |

4.7 |

11 285 550 |

Manitoba |

43 380 |

3.9 |

1 103 700 |

Saskatchewan |

16 550 |

1.7 |

963 150 |

Alberta |

58 825 |

2.0 |

2 941 150 |

British Columbia |

59 370 |

1.5 |

3 868 875 |

Yukon |

885 |

3.1 |

28 525 |

Northwest Territories |

915 |

2.5 |

37 105 |

Nunavut |

415 |

1.6 |

26 665 |

Minority Population – Canada (2001)

Minority Pop. |

Official Language Minority |

Total Pop. |

|

Number |

% |

||

Anglophones (Quebec) |

918 955 |

12.9 |

7 125 580 |

Francophones (outside Quebec) |

987 640 |

4.4 |

22 513 450 |

Linguistic Composition – Canada (2001)

First Official Language Spoken |

Number |

% |

Total Pop. |

Anglophones |

22 068 570 |

74.5 |

29 639 030 |

Francophones |

7 136 985 |

24.1 |

29 639 030 |

Over half of all Francophones in minority communities live in Ontario (527,710), while over a quarter of them live in New Brunswick (238,450). These two provinces account for 78% of all minority Francophone communities in Canada, followed by British Columbia, which now ranks fourth among provinces for its number of Francophones (59,370 or 6.0%), Alberta (58,825 or 6.0%), Manitoba (43,380 or 4.4 %), Nova Scotia (33,765 or 3.4 %), Saskatchewan (16 550 or 1.7%), Prince Edward Island (5,275 or 0.5%), the three territories (2,215 or 0.2 %) and Newfoundland and Labrador (2,100 or 0.2 %).

Apart from New Brunswick, where Francophones account for a third of the province’s population, they represent less than 5% of the population of the other provinces or territories.

Working from these basic figures and a comparison with recent census data, we note that:

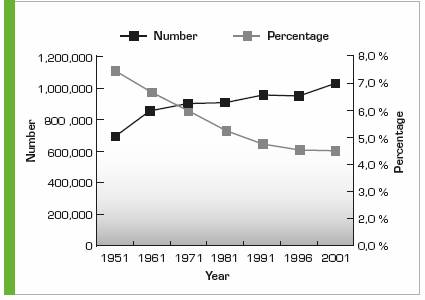

§ The number of Francophones outside Quebec has increased by about 260,000 in the last 50 years, but their share of Canada’s total population has dropped from 7.3% in 1951 to 4.4% in 2001;

Legend: Number of native speakers of French, 2001, Canada less Quebec; Number, Percent, Year.

Source: Louise Marmen and Jean-Pierre Corbeil: New Canadian Perspectives. Languages in Canada 2001 Census, 2004.

§ From 1991 to 2001, the number of Francophones in urban centres increased much more than in rural areas;

§ The Anglophone community in Quebec is aging more slowly on average than the Francophone community of Quebec.;

§ Among Anglophones outside Quebec, 22% were under the age of 15 in 2001 and 11% were over 65 years, which means there were twice as many young people as seniors;

§ Among Francophones outside Quebec, just 13% were under the age of 15 in 2001, while 15% were over 65, which means there were fewer young people than seniors;

§ In western Canada, these figures are especially worrisome since 53.4% of Fransaskois were over the age of 50 in 2001;

§ Despite the increase in the number of Francophones outside Quebec, the proportion of them who speak French at home has dropped steadily in the last 30 years;

§ 56% of Canadians whose first language is French and who live outside Quebec do not have the desired level of literacy:[6]

§ This figure is similar for all Francophone communities in Canada, including in Quebec; in New Brunswick, however, it is 66%;

§ Among Anglophones in Quebec, this figure is 43%, compared to 39% for Anglophones in all other provinces.

§ There has been significant progress in education levels among Francophones throughout Canada since 1971, which is reflected especially in the level of education among young Francophones. “The proportion of Francophones with a university degree exceeds that of Anglophones in every province outside Quebec. In Quebec, continuing a historical trend, Anglophones have higher levels of education than do Anglophones in other provinces.”[7]

§ With respect to employment and income, it has been argued that Francophones fare well on the whole compared to the national average.[8] It is argued that the disparities noted cannot be explained by language but, in some cases, by the higher proportion of Francophones living in rural areas, the greater challenges they face in obtaining a quality education, and the traditional employment sectors to which they are confined. All these hypotheses are tenuous however and are drawn into question by a recent study on income disparity between Anglophones and Francophones in New Brunswick, which demonstrates persistent gaps in income that cannot be explained by non-linguistic factors and leads to the conclusion that an individual’s linguistic group most certainly has an impact on income level. [9]

§ Over the last 50 years, the number of bilingual Canadians has increased slowly:

§ In the 2001 census, 18% of Canadians indicated that they could carry on a conversation in both official languages, compared to 12% in 1951;

§ 85% of Canadians whose first language is French and who live outside Quebec indicated they are bilingual, compared to 67% of Anglophones in Quebec;

§ Outside Quebec, the proportion of Canadians whose first language is English and who indicated they are bilingual has risen significantly, from 4% in 1971 to 7% in 2001;

§ Of the 5.2 million bilingual Canadians, 56% live in Quebec and 25% live in Ontario.

1.1.2. Francophone Communities

§ In 2001, the Francophone community of Newfoundland and Labrador had 2,100 members whose first official language spoken was French, representing 0.4% of the province’s total population, a share that has remained stable over the last thirty years;

§ After a significant drop between 1971 and 1991, the number of Francophones speaking French at home has stabilized;

§ The Francophone population is concentrated equally in St. John’s, Labrador, and on the Port-au-Port peninsula, where Francophones account for over 15% of the population of the municipality of Cap-Saint-Georges;

§ Over half the Francophones of Newfoundland and Labrador were born outside the province;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was 21% higher than the average provincial income and depends less on government transfer payments than the income of Anglophones does;

§ In 2003‑2004, 210 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12, at five schools, which indicates a drop in enrolment at English‑language schools;

§ The Francophones of Newfoundland and Labrador have a slightly higher level of education than the Anglophones;

§ The province’s Francophone community founded its first school in La Grand’ Terre in 1984;

§ In 1996, the provincial government recognized Francophones’ right to school governance and in 1997, an agreement to this effect was signed between the federal government and the government of Newfoundland and Labrador;

§ There is now an agreement between the federal and provincial governments to encourage the provincial government to offer services in French.

§ In 2001, the Francophone community of Prince Edward Island had 5,275 members whose first official language spoken is French, equal to 4.0% of province’s total population, a share that has remained stable for twenty years;

§ After a significant drop between 1971 and 1991, the number of Francophones speaking French at home has stabilized;

§ The Francophone population is concentrated primarily on the tip to the west of Summerside, an area known as Évangéline, where Francophones are in the majority in some communities;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is 48 years, compared to 37 years among Anglophones;

§ Three quarters of Prince Edward Island’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ Francophones’ average income in 2001 was lower ($23,277) than the national average, but comparable to the average income in the province, and 67% of it depended on government transfer payments;

§ In 2003-2004, 724 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 10 schools, indicating an increase in enrolment in English‑language schools;

§ The Education Act granted Francophones the right to manage their own schools in 1990;

§ In 2000, the provincial government proclaimed the French-Language Services Act, which stipulates that provincial laws and regulations must now be issued in both official languages.

§ In 2001, Nova Scotia’s Francophone community had 33,765 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 3.8% of the province’s total population, a share that has dropped somewhat in the last twenty years;

§ After a significant drop between 1971 and 1996, the number of Francophones who speak French at home started to increase as of 1996;

§ The Francophone population is concentrated equally in Cape Breton, in the Southwest and in Halifax, and represents a majority in Clare, Argyle, Inverness and Richmond;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is 46, compared to 39 for Anglophones;

§ Close to three-quarters of Nova Scotia’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was slightly higher than the average provincial income, and government transfer payments accounted for a declining share of employment income;

§ In 2003-2004, 4,151 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 20 schools, indicating an increase in enrolment in English‑language schools;

§ In 1981, the provincial government passed legislation recognizing Francophones’ right to be educated in French and the school board was established a few months later;

§ A French Language Services Act was passed in October 2004, coming into force on December 31, 2006.

§ In 2001, New Brunswick’s Francophone community had 238,450 members whose first official language spoken was French, which is 33.1% of the province’s total population, a share that has remained stable for thirty years;

§ New Brunswick is the only officially bilingual province in Canada;

§ The proportion of Francophones who speak French at home has remained stable for thirty years;

§ The Francophone population is spread out over the province, but there is a strong majority in the Madawaska region, whose urban centre is Edmunston, on the Acadian peninsula, whose urban centre is Bathurst, and in the Moncton/Dieppe region;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is 40 years, compared to 38 years among Anglophones, a smaller difference that in the other Atlantic provinces;

§ 90% of New Brunswick’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ Francophones in New Brunswick have lower levels of education than Anglophones, and half of them have not completed high school;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $22,448, compared to $24,091 for Anglophones;

§ In 2003-2004, 35,050 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 107 schools, indicating a drop in the proportion of students enrolled in English-language schools;

§ The provincial government passed its Official Languages Act in 1969, which was revised in 2002. The Act Recognizing the Equality of the Two Official Linguistic Communities in New Brunswick, adopted in 1981, was incorporated into the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1993 following the defeat of the Charlottetown Accord.

§ In 2001, Ontario’s Francophone community had 527,710 members whose first official language spoken was French, representing half of all Francophones in minority communities in Canada but just 4.7% of the province’s population, a share that has been decreasing slowly but steadily over the last fifty years;

§ The proportion of Francophones who speak French at home has dropped over the last thirty years;

§ The Francophone population is spread out over the province but the greatest concentrations are in Eastern Ontario (Ottawa and Prescott‑Russell and Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry counties), Northern Ontario (urban centres of Timmins and Sudbury), and the greater Toronto area and surrounding areas, where over 20% of Ontario’s Francophones live, although they account for only 2% of the population;

§ Two-thirds of Ontario’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ Francophones in Ontario have slightly less education than Anglophones, but the gap has shrunk significantly in the last thirty years;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $32,750, just $100 lower than the average income of Anglophones;

§ In 2003-2004, 89,367 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 415 schools, indicating a slight drop in enrolment in English-language schools;

§ The provincial government passed the French Language Services Act in 1986.

§ In 2001, Manitoba’s Francophone community had 43,380 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 3.9% of the province’s total population, a share that has been dropping steadily for fifty years;

§ The proportion of Francophones who speak French at home has declined over the last thirty years;

§ Two-thirds of Francophones live in cities, primarily in the Winnipeg / St. Boniface area, and the remaining third live primarily in the rural municipalities around Winnipeg or in the south of the province, which means that the Franco-Manitoban community is by far the most geographically concentrated.

§ 80% of Manitoba’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is 46 years, compared to 36 years for the population as a whole;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $27,329, which is about $1,000 above the average provincial income;

§ In 2003-2004, 5,171 students were educated in French, from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 29 schools, a stable share as compared to enrolment in English-language schools;

§ Although the Constitution recognized linguistic duality in 1870, various legislative measures abolished it between 1890 and 1916, and the official status of French was not restored until 1979, following a Supreme Court decision;[10]

§ Francophones in Manitoba obtained school governance rights in 1993;

§ Manitoba has 15 officially bilingual municipalities, in addition to parts of the city of Winnipeg.

§ In 2001, Saskatchewan’s Francophone community had 16, 550 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 1.7% of the province’s total population, a share that has dropped slowly but steadily for fifty years;

§ The proportion of Francophones who speak French at home has been in decline for the last thirty years;

§ Half of Francophones live in the cities of Saskatoon, Regina and Prince Albert, and the others are spread out over the province, with a significant proportion of Francophones in a few small communities, including Gravelbourg, Ponteix, Saint-Louis, Domremy and Zenon Park;

§ 80% of Saskatchewan’s Francophones were born in the province;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is very high at 52 years, compared to 36 years for the general population;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $27,888, about $2,000 higher than the provincial average;

§ In 2003-2004, 1,060 students were educated in French, from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 13 schools, which represents a slight increase as compared to enrolment in English-language schools;

§ Although French language education was allowed under certain conditions when the province was founded in 1905, it was completely abolished between the world wars and was gradually reintroduced in the 1960s;

§ The right to school governance was granted to Francophone parents in 1990.

§ In 2001, Alberta’s Francophone community had 58,825 members whose first official language spoken was French, representing 2% of the province’s population, a share that has been increasing since 1996;

§ From July to September 2006, 2,900 more people left Quebec for Alberta than the opposite. Assuming they were predominantly Francophones, that would mean that, in just three months, Alberta’s Francophone community grew by the equivalent of the total Francophone population of Newfoundland and Labrador.[11]

§ About two-thirds of Francophones live in the cities of Calgary, Edmonton and outlying areas while the rest are spread out over the province, with greater concentrations in a few regions such as Fahler and in a few other communities in the northeast and northwest of Alberta;

§ Less than half of Alberta’s Francophones were born in the province which, like the Francophone community in British Columbia, makes it a community with less traditional roots, but one that is also younger than other Francophone communities in western Canada;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is nevertheless higher (44 years) than that of 35 years for the province as a whole, although the gap is shrinking;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $32,058, slightly higher than the average income in the province;

§ In 2003-2004, 3,619 were educated in French, from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 23 schools, a share that is growing relative to enrolment in English‑language schools;

§ The province granted Francophones school governance rights in 1993.

§ In 2001, British Columbia’s Francophone community had 59,370 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 1.5% of the total population, as compared to 1.2% in 1971;

§ Very few Francophones in British Columbia were born in the province, about 10%, but there appears to be an increase in French being spoken at home, no doubt due to an increase in Francophone immigration;

§ A bit less than half of Francophones live in the metropolitan Vancouver area, 10% in the Victoria region, and the others are spread out over the province, never exceeding 5% of the local population in 2001;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is higher at 46 years than that of 38 years for the province as a whole;

§ The average income for Francophones in 2001 was $26,293, on par with the average provincial income;

§ In 2003-2004, 3,147 students were educated in French, from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 40 schools, an increase in enrolment compared to English‑language schools;

§ British Columbia has had French-language education program since 1977 and the provincial government granted Francophone school governance throughout the province in 1999.

§ In 2001, Yukon’s Francophone community had 885 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 3.1% of the total population, a share that has increased over the past twenty-five years;

§ The vast majority of Francophones are in Whitehorse and surrounding areas;

§ Less than 20% of Francophones were born in the territory;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is higher at 42 years than the that of 36 years for the general population;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was $31,541, on par with the average income for the territory;

§ In 2003-2004, 119 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at Émilie-Tremblay School, a stable share compared to enrolment in English-language schools;

§ Yukon’s Official Languages Act was passed in 1988 and various agreements between Yukon and the federal government provide a framework for the delivery of services to Francophones.

§ In 2001, the Francophone community of the Northwest Territories had 915 members whose first official language spoken was French, or 2.5% of the total population, a share that has grown since 1996 after a number of years of decline;

§ Two-thirds of Francophones live in Yellowknife and surrounding areas and the remainder live throughout this huge territory;

§ Less than 20% of Francophones were born in the territory;

§ The median age of those whose first language is French is higher at 40 years than that of 30 years for the general population;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was high at $44,056, $9000 above the average for the territory;

§ In 2003-2004, 128 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at Allain-Saint-Cyr school in Yellowknife and at École Boréale in Hay River, a stable share as compared to enrolment at English-language schools;

§ The first French-language education program dates back to 1989 and the first all-French school was built in 1999.

§ In 2001, Nunavut’s Francophone community had 415 members whose first official language spoken was French, representing 1.6% of the territory’s total population; any changes in that share will not be known until the 2006 census results are published;

§ Less than 10% of Francophones were born in the territory;

§ The median age of those whose first official language is French is higher at 39 years than that of the general population (30 years), but lower than in most Francophone communities in Canada;

§ The average income of Francophones in 2001 was high at $47,534, $20,000 higher than the average income for the territory;

§ In 2003-2004, 38 students were educated in French from kindergarten to Grade 12 at Trois-Soleils school, in Iqaluit;

§ The first French-language education program dates back to 1989 and the first all-French school was built in 1999.

1.1.3. Quebec’s Anglophone Community

§ In 2001, Quebec’s Anglophone community had 918,955 members whose first official language spoken was English, or 12.9% of the province’s total population, a share that has remained stable over the last thirty years;

§ The number of native speakers of English in Quebec (591,379) has been in decline for fifty years, and immigrants account for an increasingly large share of Quebec’s Anglophone community, although the proportion of immigrants whose first language is English has clearly decreased over the past thirty years;

§ It is estimated that about 225,000 more native speakers of English left Quebec for other provinces between 1971 and 2001 than vice versa;

§ Three quarters of Quebec’s Anglophones live in the Montreal area, and the Anglophones in the Eastern Townships now account for just 6% of the region’s population, a significant drop over the last 30 years;

§ Quebec’s Anglophone community is aging more slowly on average than the Francophone community;

§ The number of Anglophones who speak English at home is decreasing;

§ The average income of Anglophones in 2001 was $44,572, compared to $38,669 for Francophones in Quebec;

§ In 2003-2004, 108,160 students were educated in English from kindergarten to Grade 12 at 350 schools in nine school boards;

§ Quebec’s Anglophone community has the highest level of education in Canada;

§ Since 1998, Quebec’s school boards have been divided along linguistic lines: English-language and French-language.

1.2. The Official Languages and the Constitution

What is commonly knows as Canada’s Constitution is a series of legal documents and established conventions — not necessarily written — that together make up the country’s fundamental law, which guides the courts and forms the basis for the interpretation of all other legislation. Among the thirty or so pieces of constitutional legislation passed since Confederation,[12] two are especially important: the Constitution Act, 1867, formerly known as the British North America Act, and the Constitution Act, 1982, which includes the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Canada’s two official languages were first recognized in the Constitution Act, 1867. Section 133 states:

Either the English or the French Language may be used by any Person in the Debates of the Houses of the Parliament of Canada and of the Houses of the Legislature of Quebec; and both those Languages shall be used in the respective Records and Journals of those Houses; and either of those Languages may be used by any Person or in any Pleading or Process in or issuing from any Court of Canada established under this Act, and in or from all or any of the Courts of Quebec.

The Acts of the Parliament of Canada and of the Legislature of Quebec shall be printed and published in both those Languages.[13]

In the Constitution Act, 1982, linguistic issues are addressed in sections 16 to 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Sections 16 to 19 strengthen prior constitutional provisions and incorporate the key elements of the Official Languages Act of 1969 (see section 1.3) into the Constitution. They make English and French the “official languages of Canada” and extend their equality of status and equal rights and privileges not only to the country’s legislatures, courts and legislation, but also to the institutions of the “government of Canada.” They also extend these provisions to the government of New Brunswick and since 1993, include the recognition of the equality of rights and privileges of English and French linguistic communities in the province, including their right to culturally distinct educational institutions.

Section 20 stipulates that the public has the right to communicate with, and to receive available services from, any head or central office of an institution of the Parliament or Government of Canada in English or French. The public has the same right with respect to any other office of any such institution where “there is a significant demand” or where “due to the nature of the office, it is reasonable that communications with and services from that office be available in both English and French.” Paragraph 2 of section 20 provides that any member of the public in New Brunswick has the right to communicate with, and to receive available services from, any office of an institution of the legislature or government of New Brunswick in English or French.

Sections 16 to 20 were subsequently clarified and strengthened by comparable provisions of the Official Languages Act of 1988.

Sections 21 and 22 are designed to harmonize the Charter with other constitutional provisions as to the issues addressed in the above language-related sections.

Section 23 pertains to minority-language education rights. It begins as follows:

(1) Citizens of Canada:

a) whose first language learned and still understood is that of the English or French linguistic minority population of the province in which they reside, or

b) who have received their primary school instruction in Canada in English or French and reside in a province where the language in which they received that instruction is the language of the English or French linguistic minority population of the province, have the right to have their children receive primary and secondary school instruction in that language in that province

Pursuant to section 59 of the Constitution Act, 1982, subsection (1)a) of this section is not applicable to Quebec because that province’s legislature must first proclaim its validity, which it has yet to do. As a result, it applies only to Francophone minorities outside Quebec.

Subsection (2) of section 23 provides that citizens of Canada of whom any child has received primary or secondary school instruction in English or French in Canada, have the right to have all their children receive primary and secondary school instruction in the same language.

The right established in subsections (1) and (2) is however subject to subsection (3), which stipulates that this right applies wherever in the province the number of children of citizens who have this right is sufficient to warrant publicly funded minority language education. This includes public funding for minority language educational facilities, where numbers warrant.

In contrast to sections 16 to 20, the provisions of section 23 are not repeated in the Official Languages Act of 1988 since education falls primarily under provincial jurisdiction. As a result, its provisions do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Commissioner of Official Languages. The courts are instead responsible for determining its application, especially as regards the responsibilities of provincial governments towards official language minority communities. A number of cases relating to this section have set precedents as cases involving legal aspects of the official languages on which the courts had not yet ruled. One of the most important of these was Mahé v. Alberta in 1990,[14] in which the Supreme Court established an approximate formula to calculate the number of children justifying a separate educational institution. This decision also established school governance rights for the parents of children receiving this minority-language education. This decision has been decisive in the recent development of Francophone communities outside Quebec, as were the subsequent decisions in Beaulac (1999) and Arsenault‑Cameron (2000). The Supreme Court reaffirmed among other things that “language rights must, in all cases, be interpreted purposively, in a manner consistent with the preservation and development of official language communities in Canada.”[15]

1.3. The Official Languages Act

The federal government enacted the first Official Languages Act in July 1969, following the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. In 1982, the entrenchment of linguistic rights in the Constitution through the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms extended the scope of linguistic rights and led to the amendment of the Official Languages Act in September 1988.

The purpose of the Official Languages Act of 1988 is to:

a) ensure respect for English and French as the official languages of Canada and ensure equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all federal institutions, in particular with respect to their use in parliamentary proceedings, in legislative and other instruments, in the administration of justice, in communicating with or providing services to the public and in carrying out the work of federal institutions;

b) support the development of English and French linguistic minority communities and generally advance the equality of status and use of the English and French languages within Canadian society; and

c) set out the powers, duties and functions of federal institutions with respect to the official languages of Canada.[16]

The Act is divided into fourteen parts, and parts I to V take precedence over all other federal legislation and regulations, except for the Canadian Human Rights Act. This is one reason why it is known as a quasi-constitutional statute.

Parts I to III of the Act provide greater detail on the provisions of sections 16 to 19 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms as to the proceedings of Parliament (Part I), legislative instruments (Part II) and the administration of justice (Part III).

Part IV of the Act pertains to communications with the public and the provision of services, and provides greater detail on the provisions of section 20 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Pursuant to this part, the public has the right to communicate with and receive services in either official language from the head or central office of federal departments and agencies where a) there is “significant demand” and b) where it is warranted by the “nature of the office,” and wherever services are provided to the travelling public where “demand warrants.” The Official Languages Regulations adopted in December 1991 defined the terms “nature of office” and “significant demand.”

Part V pertains to the language of work for employees of federal institutions in regions designated bilingual. These regions are identified by Treasury Board and are located in Quebec, New Brunswick and Ontario. In regions not designated bilingual, members of the official language minority must receive comparable treatment to that received by the other linguistic group where the situation is reversed. The application of Part V is not the subject of regulations, but its various provisions have been fleshed out in Treasury Board guidelines.

Part VI sets out the government’s commitment to ensuring that Anglophones and Francophones have equal opportunities for employment and advancement in federal institutions, based on their demographic weight, but subject to certain conditions. It is primarily this part that is used to support the demands of Quebec’s Anglophone community, which is demographically under-represented in the federal public service in Quebec.

Part VII of the Act is certainly the cornerstone for the vitality of official language minority communities. Not included in the Official Languages Act of 1969, it sets out the federal government’s commitment to enhancing the vitality of linguistic minorities, supporting their development and fostering the full recognition and use of English and French in Canadian society.

Since Bill S-3 was passed in November 2005, federal institutions are now required to take “positive measures” to follow through on this commitment, and the provisions of Part VII are now subject to legal remedy. Prior to this, Part VII was merely declaratory, meaning that it did not include an obligation to act and did not create rights subject to recognition by the courts. All institutions subject to the Act must now re-evaluate their actions as regards the two aspects of the federal commitment set out in Part VII: supporting the official language minority communities and fostering linguistic duality.

The Department of Canadian Heritage is responsible for coordinating the efforts of all federal institutions pursuant to Part VII. In this regard, the minister submits an annual report to Parliament on matters relating to her official languages mandate.

Part VIII describes Treasury Board’s responsibilities pursuant to Parts IV to VI of the Act. Part IX describes the powers of the Commissioner of Official Languages, which are to enforce the Act within federal institutions and uphold the rights of official language minorities, as well as promote linguistic duality and the equality of status of English and French in Canadian society. Part X sets forth the court remedy available, while Parts XI to XIV pertain to general aspects, related amendments made by the Act, as well as transitional provisions, and repeal and coming into force provisions.

1.4. Action Plan for OFFICIAL Languages

The Action Plan for Official Languages announced in March 2003 provided for an injection of over $751 million over five years in three key areas: education ($381.5 million), community development ($269.3 million) and the public service ($64.6 million). Specific measures were also included for the language industries ($20 million) and for the implementation of the Accountability Framework applicable to designated federal institutions ($16 million). An Enabling Fund for human resources development and community economic development was added to the Action Plan in March 2005, adding $36 million over three years to the total investments under the Plan.

The Action Plan is the culmination of a process that began in 2001, based on three considerations:

1) Linguistic duality is a fundamental aspect of Canadian identity. Together with its openness to global cultural diversity, Canada has maintained this commitment to its linguistic roots, since over 98% of residents indicate they speak one of the official languages. Official-language minority communities have contributed a great deal to maintaining this aspect of Canadian identity. The federal government therefore has a responsibility to these communities that have tirelessly cultivated the country’s cultural roots.

2) Linguistic duality is a competitive advantage for Canada internationally. Far from creating “two solitudes,” our duality offers Canadians a window on linguistic plurality that is unique in the American continent, making it easier to forge ties with a multilingual Europe and encouraging us to help the Aboriginal peoples of Canada preserve their linguistic heritage. Moreover, learning a second language is often a springboard to learning a third and fourth language.

3) Since the first official languages policy was established in the late 1960s, there have been significant changes in individual and community ways of life. The cosmopolitan character of Canada’s large urban centres places official language minorities in competition with other cultural communities with respect to services in their language. At the same time however, minority Francophone communities are now in a much better position to assert their rights, and their institutions are much more numerous and stronger. Youth retention, low birth rates and exogamous marriages do however weaken the social fabric of these communities. Finally, the relatively strong state of public finances makes it easier to consider long-term support for the development of these communities.

Based on these considerations, the Government of Canada announced in April 2001 the creation of a committee of ministers, chaired by the Honourable Stéphane Dion, to “consider strong new measures that will continue to ensure the vitality of minority official-language communities and ensure that Canada’s official languages are better reflected in the culture of the federal public service.”[17]

To achieve this, the Action Plan establishes:

1) the Accountability and Coordination Framework setting out and reminding federal officials of their respective responsibilities, while establishing a horizontal coordination process for actions stemming from the multiple elements of Official Languages policy;

2) three key areas for action:

a) education, including both minority language education, pursuant to section 23 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and second-language instruction, in order to promote linguistic duality;

b) community development, which seeks to foster better access to public services in health care, early childhood development and justice, and create economic development tools;

c) the public service, whereby the federal government is to set an example by enhancing the provision of federal services in both official languages, the participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians in federal institutions and the use of the official languages at work; and

3) greater support for the development of language industries in order to address the shortage of specialized language training and translation instructors and by expanding the range of careers that foster the language skills required in the federal public service.

4) In March 2005, the Government of Canada added to the Action Plan an Enabling Fund for official language communities, which rounds out existing programs that support human resources development and community economic development.

1.4.1. Accountability and Coordination Framework

This framework is intended to make federal institutions more aware of their obligations under the Official Languages Act, to provide for ongoing consultation with official language communities and to establish an interdepartmental coordination mechanism on official languages. It includes 45 sections, the first 30 of which clearly spell out the responsibilities of federal institutions, especially those of the Department of Canadian Heritage, which is responsible for coordinating all measures taken by federal institutions to enhance the vitality of official language minority communities (Part VII of the Official Languages Act), and those of Treasury Board, which is responsible for services to the public (Part IV), language of work (Part V) and the equitable participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians in the federal public service (Part VI).

These sections spell out federal institutions’ current responsibilities. The framework goes one step further by adding new responsibilities under five categories:

1) An official languages perspective in the development of all new initiatives by federal institutions. Section 7 of the Framework stipulates that “all federal institutions are required to analyse the impact of proposals contained in memoranda to Cabinet on the language rights of Canadians and federal public servants.”[18]

2) The implementation by each federal institution of a systematic process for raising employee awareness, evaluating impact on linguistic duality and community development, consulting interested publics, “especially representatives of official language minority communities, in connection with the development or implementation of policies or programs,”[19] and the evaluation of results.

3) The establishment of a horizontal coordination mechanism focussed on the minister responsible for official languages. This minister must now ensure that federal institutions fulfill their responsibilities under the Official Languages Act and the Action Plan. This monitoring role will be supported by the Committee of Deputy Ministers on Official Languages and a secretariat that is part of the Privy Council Office.[20]

4) A larger evaluation role for the Department of Justice to allow it to examine the legal implications for official languages of initiatives by federal institutions.

5) The establishment of an evaluation process for measures taken under the Action Plan, including the preparation of a midterm report and an overall evaluation at the end of the implementation period.

The Action Plan includes a budget of $13.5 million allocated over five years to the Privy Council Office for the overall coordination of the plan. In February 2006, this budget was transferred to the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Over half of the $751 million investment set out in the Action Plan is earmarked for education, with the following objectives:

§ Increase the proportion of rights holders enrolled in French-language schools from 68% in 2003 to 80% in 2013;

§ Support for French-language instruction for Anglophones in Quebec, and support to English-language schools outside Montreal;

§ Increase the proportion of high school graduates with a working knowledge of their second official language from 24% in 2003 to 50% in 2013;

§ Increase the number of participants in summer language bursary and language monitor programs;

§ Promote research.

In order to achieve these ambitious objectives, the Action Plan includes a significant increase in funding for federal-provincial-territorial agreements: $209 million over five years for existing minority-language education programs and $137 million over five years for second-language instruction programs. These agreements represent an estimate of the additional costs incurred by each province and territory in order to offer minority-language education and second-language instruction, as compared to what it would cost for the same number of students if they were taught in the majority language. The Action Plan also includes a $35.5 million increase for the official language monitor and summer bursary programs.

In order to foster the vitality of official language minority communities, the Action Plan identifies seven key areas of activity: early childhood development, health services, justice, immigration, economic development, partnership with the provinces and territories and support for community life.

With respect to early childhood development ($22 million over five years), three commitments were made:

§ $7.4 million for literacy development services;

§ $10.8 million for research in the form of pilot projects to evaluate how French‑language child care services influence the cultural and linguistic development of young children;

§ $3.8 million in support of national organizations for the sharing of knowledge on early childhood development in official language minority communities.

With respect to health services, the Action Plan provides for a total investment of $119 million broken down as follows:

§ $14 million for networking to help establish regional networks linking health care professionals, institution managers, local elected officials, teachers and community representatives;

§ $75 million for workforce training, recruitment and retention, including $63 M administered by the Consortium national de formation en santé pancanadien, whose objective is to train 1000 new Francophone health professionals for minorities communities by 2008;

§ $30 million, including $10 million for Quebec’s Anglophone community, for the Fonds pour l’adaptation des soins de santé primaires (Entente Santé 2000), which represents a substantial increase in funding for the federal-provincial agreement that was concluded in 2000 and expired in 2006.

With respect to justice, the Action Plan provides $45.5 million for two groups of initiatives:

§ $27 million for upholding the legal obligations stemming from the implementation of the Legislative Instruments Re-Enactment Act[21] and Contraventions Act issues;[22]

§ $18.5 million for targeted measures to improve access to justice in both official languages, including funding for federal-provincial-territorial initiatives, funding for associations of French-speaking jurists, the creation of a community consultation mechanism, and the development of training tools for counsel employed with the Department of Justice.

With respect to immigration, the Action Plan provides $9 million over five years, administered by Citizenship and Immigration Canada, which previously had no stable funding for official language minority communities. This funding is earmarked for market studies and the production of promotional material to be used abroad and to support information centres for Francophone immigrants and French correspondence courses.

With respect to economic development, the Action Plan includes:

§ $13 million over five years for the Francommunautés virtuelles programs, which seeks to increase online services in French that bring together Francophone and Acadian communities;

§ $7.3 million over five years from the existing budgets of Human Resources Development for internships relating to economic development, as well as $2 M in additional funding allocated to regional development agencies;

§ $10 million over five years for pilot projects to develop technology infrastructure in order to enhance the services offered;

§ $8 million over five years to improve the information and reference services offered by Human Resources Development, Industry Canada and regional development agencies, within existing structures, including the hiring of bilingual counsellors.

As to partnership with the provinces and territories, the Action Plan includes an increase in the contribution by Canadian Heritage to federal-provincial-territorial agreements for official language minority services. These agreements encourage and help provincial and territorial governments improve their services to the official language minority community.

With respect to support for community life, the Action Plan includes an additional investment of $19 million over five years to fund projects submitted to Canadian Heritage that are likely to help communities, especially for community centres, culture and the media.

With planned investments of $64.6 million over five years, the revitalization of linguistic duality in the federal public service is a key element of the Action Plan for Official Languages. While this element of the plan will be addressed indirectly in this study, let us recall its main features:

§ $14 million for Treasury Board investments to support initiatives by other departments and agencies, including the creation of a Regional Partnership Fund to adapt federal initiatives locally, and an Official Languages Innovation Fund to support the services offered in both official languages and a corresponding workplace;

§ $12 million increase to the budgets of the Official Languages Branch of Treasury Board Secretariat in order to develop compliance monitoring mechanisms for federal institutions;

§ $38.6 million to the Public Service Commission to increase bilingual capacity in the public service by encouraging the hiring of candidates who are already bilingual, offering training to those who are not and fostering the retention and development of language skills.

In an attempt to counter the fragmentation and lack of visibility of these industries, to foster the recruitment of a sufficient number of replacement workers and to support research, the Action Plan includes a $20 million investment allocated as follows:

§ $5 million for the establishment of a representative organization and to fund its coordination activities;

§ $5 million for market promotion and branding initiatives in Canada and internationally, to increase visibility for the industries and attract new talent;

§ $10 million for the establishment of a research centre on language industries.

The Enabling Fund was created in March 2005 to boost the work of the Réseaux de développement économiques et d’employabilité (RDÉE) and the Community Economic Development and Employability Committees (CEDEC), following the mandate review of the Official Language Minority Communities Support Fund, and in order to better coordinate requests for assistance submitted to various federal institutions. This Fund has annual funding of $12 million for the last three years of the Action Plan.

As stated above, the purpose of the Action Plan was twofold: to foster the vitality of official language minority communities and to more strongly root linguistic duality in the federal public service. This study will focus on assessing progress on the first of these two broad objectives in order to consider what action should be taken when the Action Plan expires at the end of the fiscal year ending on March 31, 2008.

1.5. Official Languages Programs of The Department of Canadian Heritage

The Minister of Canadian Heritage encourages and promotes the coordination and implementation by federal institutions of the federal government’s commitment to enhancing the vitality and supporting the development of official language minority communities, and fostering the full recognition and use of English and French in Canadian society.

As part of this mandate, pursuant to Part VII of the Official Languages Act, the Minister of Canadian Heritage[23] takes measures to advance the equality of status of English and French in Canadian society, including measures to:

a) Enhance the vitality of the English and French linguistic minority communities in Canada and support and assist their development;

b) encourage and support the learning of English and French in Canada;

c) foster an acceptance and appreciation of both English and French by members of the public;

d) encourage and assist provincial governments to support the development of English and French linguistic minority communities generally and, in particular, to offer provincial and municipal services in both English and French and to provide opportunities for members of English or French linguistic minority communities to be educated in their own language;

e) encourage and assist provincial governments to provide opportunities for everyone in Canada to learn both English and French;

f) encourage and cooperate with the business community, labour organizations, voluntary organizations and other organizations or institutions to provide services in both English and French and to foster the recognition and use of those languages;

g) encourage and assist organizations and institutions to project the bilingual character of Canada in their activities in Canada or elsewhere; and

h) with the approval of the Governor in Council, enter into agreements or arrangements that recognize and advance the bilingual character of Canada with the governments of foreign states.

i) ensure public consultation on the development of policies and review of programs relating to the advancement and the equality of status and use of English and French in Canadian society. [24]

The Minister of Canadian Heritage tables an annual report in Parliament on matters relating to her official languages mandate. The total expenditures of the Official Languages Support Programs Branch for fiscal year 2005-2006 were $341,478,897, as compared to $300,263,331 in 2004-2005, and $264,257,559 in 2003-2004.[25]

These expenditures are allocated to two main programs:

§ The Development of Official-Language Communities program ($232 M),[26] has two components:

§ the Community Life component ($52.9 M), which includes the following sub-components:

§ Cooperation with the Community Sector ($37.4 M) includes grants and contributions to community organizations as well as Strategic Fund expenditures, a discretionary fund with an annual value of approximately $5 million, from which the Department funds major projects as well as interregional or nationwide projects;

§ Intergovernmental Cooperation on Minority-Language Services ($14.3 M): includes federal-provincial-territorial agreements on improving provincial, territorial and municipal services in the minority language;

§ Interdepartmental Partnership with Official-Language Communities (IPOLC) ($3.9 M):[27] allows Canadian Heritage to transfer funding to another federal department or agency whose program can increase the vitality of official-language minority communities;

§ Young Canada Works (minority) ($1.1 M): offers students summer employment in their field of study in an official‑language minority community where they can use their first official language;

§ and the Minority-Language Education component ($179.4 M), which includes two subcomponents:

§ Intergovernmental Cooperation ($178.1 M): includes federal‑provincial-territorial agreements, concluded directly with the provinces and territories or through the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) ($175.1 M), as well as development bursaries and monitor positions for young Francophones from minority communities ($3.0 M);

§ Cooperation with the Non-Governmental Sector ($1.2 M): supports projects contributing to an increase in the production and dissemination of knowledge, methods and tools relating to minority-language education.

§ The Enhancement of Official Languages program ($109.2 M), also has two components:

§ Promotion of Linguistic Duality ($4.6 M) has two sub‑components:

§ Support for Linguistic Duality (Appreciation and Rapprochement) ($4.1 M) includes Collaboration in Promotion ($3.3 M), which supports Canadian non-profit organizations seeking primarily to promote linguistic duality in Canada, as well as Support for Innovation ($0.8 M), which supports projects enhancing the visibility of Canada’s linguistic duality;

§ Cooperation with Voluntary Sector (Bilingual Capability) ($0.5 M), which refers primarily to Support for Interpretation and Translation for organizations wishing to encourage both official languages at public events and increase the number of documents available in both official languages, as well as the residual component of Support for Innovation, which can be used to promote services in both official languages.

§ Second-Language Learning ($104.5 M) has two sub‑components:

§ Intergovernmental Cooperation ($101.6 M): includes federal‑provincial-territorial agreements concluded directly with the provinces or territories or through the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC) ($80.4 M), as well as Complementary Support for Language Learning, which includes second-language immersion bursaries and monitor positions ($21.2 M);

§ Cooperation with Non-Governmental Sector ($0.5 M): supports projects contributing to an increase in the production and dissemination of knowledge, methods and tools relating to second-language teaching;

§ Young Canada Works (Second Language or Bilingualism) ($2.4 M): offers students summer employment in their field of study in their second official language and internships to build advanced skills to make the transition to Canada’s language‑based industries.

1.6. Brief analysis of financial data

§ Expenditures for all programs administered by Canadian Heritage have increased by about 25% over the last three years, rising from $272.94 million in 2002-2003 to $341.48 million in 2005-2006, for an increase of $68.5 million. This increase is entirely attributable to the increased investment in fiscal years 2004-2005 and 2005-2006, following a drop in 2003-2004.

§ Nearly $40 million of this $68.5 million increase went to Second Language Learning, with expenditures increasing 61% over the last three fiscal years. By contrast, expenditures on Minority Language Education increased by 21% over the same period, by $31.2 million. There was a slight decrease in investment in the Promotion of Linguistic Duality component over the last three fiscal years, while funding for the Community Life component fell by $2 million over the same period, for a 3.6% decrease.

§ When the Action Plan for Official Languages was launched, $346 million was allocated to be spent over five years on Minority Language Education and Second Language Learning, under federal-provincial/territorial agreements for education. This was in addition to the $943 million already allocated under regular programs, for a total of $1.289 billion over five years. After three fiscal years, $649.2 million has been spent, including $158.0 million from the amount allocated under the Action Plan. As to the agreements for education, adding the funding from regular programs and the investments from the Action Plan, that leaves $639.9 million to be spent in fiscal years 2006-2007 and 2007-2008, including $188.0 million from the amount specifically allocated under the Action Plan. Yet the Minister for the Francophonie and Official Languages announced that $514.0 million will be spent over the last two fiscal years covered by the Action Plan, which would maintain current spending levels. [28] A shortfall of about $125.9 million ($639.9 - $514.0 million) should therefore be expected in the amount spent on education at the end of the five-year Action Plan. This is equivalent to 36.4% of the total budget to be spent on education under the Action Plan.

§ By the end of the five years covered by the Action Plan, on March 31, 2008, if 2005-2006 spending levels are maintained, it is anticipated that about $115 million less than planned will have been spent under federal-provincial-territorial agreements for education in French-language schools outside Quebec. For second language instruction programs, the shortfall is expected to be about $10 million.

§ On the whole, after a slow start in 2003-2004 and 2004-2005, investments under the Action Plan appeared to be moving forward as of fiscal year 2005-2006. Yet further to the investments under the Action Plan, the investment in ongoing programs dropped significantly (by 26%) for the Minority Language Education component, with $37.5 million less in 2005‑2006 than in 2002-2003, dropped slightly for the Community Life component, while there was a significant increase (26% or $11.3M) in the amount allocated to second-language learning agreements during the same period.

CANADIAN HERITAGE |

|||||||||||

2002-2003 |

2003-2004 |

2004-2005 |

2005-2006 |

||||||||

OFFICIAL LANGUAGES SUPPORT PROGRAMS |

$272,939,386 |

$264,535,172 |

$300,337,722 |

$341,470,899 |

|||||||

Data from Public Accounts |

$267,474,698 |

$264,257,559 |

$300,263,331 |

$341,478,897 |

|||||||

Canadian Identity Program |

|||||||||||

Grants |

|||||||||||

Organizations |

$5,975,246 |

$5,933,186 |

|||||||||

Contributions |

|||||||||||

Programs |

$209,077,420 |

$190,143,422 |

|||||||||

Organizations |

$52,422,032 |

$68,180,951 |

|||||||||

DEVELOPMENT OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGE COMMUNITIES |

$203,069,399 |

$192,978,558 |

$214,473,063 |

$232,287,348 |

|||||||

Data from Public Accounts |

$209,311,144 |

$231,137,454 |

|||||||||

Community Development and Capacity Building Program |

|||||||||||

Grants |

$4,595,787 |

$4,972,337 |

|||||||||

Contributions |

$204,715,357 |

$226,165,117 |

|||||||||

COMMUNITY LIFE COMPONENT |

$54,883,938 |

$57,398,442 |

$51,953,917 |

$52,894,007 |

|||||||

Cooperation with Community Sector / Community Support |

$34,746,648 |

$37,031,435 |

$33,383,847 |

$37,437,226 |

|||||||

Regular program |

$28,232,251 |

$25,347,365 |

$24,435,793 |

$28,541,417 |

|||||||

Strategic Fund |

$6,514,397 |

$9,547,572 |

$6,129,677 |

$4,845,809 |

|||||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$2,136,498 |

$2,818,377 |

$4,050,000 |

||||||||

Administration of Justice in Both Official Languages |

$649,000 |

||||||||||

FPT agreements on minority language services |

$13,171,426 |

$14,151,205 |

$13,339,560 |

$14,306,888 |

|||||||

Regular program |

$13,171,426 |

$13,462,543 |

$11,572,718 |

$11,330,808 |

|||||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$688,662 |

$1,766,842 |

$2,976,080 |

||||||||

Interdepartmental Partnership with Official Language Communities |

$6,316,864 |

$5,321,876 |

$3,906,677 |

$- |

|||||||

Young Canada Works (minority) |

$893,926 |

$1,323,833 |

$1,149,893 |

||||||||

MINORITY LANGUAGE EDUCATION COMPONENT |

$148,185,461 |

$135,580,116 |

$162,519,146 |

$179,393,341 |

||||||

FPT agreements on minority language education |

$144,819,060 |

$132,538,505 |

$159,443,027 |

$175,139,639 |

||||||

Regular program |

$144,819,060 |

$122,763,505 |

$116,238,066 |

$107,365,771 |

||||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$9,775,000 |

$43,204,961 |

$67,773,868 |

|||||||

Complementary Support for Language Learning |

$2,257,351 |

$2,278,568 |

$2,285,619 |

$3,063,702 |

||||||

Regular program |

$2,190,478 |

$1,662,819 |

$2,361,702 |

|||||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$88,090 |

$622,800 |

$702,000 |

|||||||

Summer Bursaries for Francophones Outside Quebec |

$515,226 |

|||||||||

Official Language Monitors (minority) |

$1,742,125 |

|||||||||

Cooperation with Non-Governmental Sector |

$763,043 |

$790,500 |

$1,190,000 |

|||||||

Language training and development program |

$1,109,050 |

|||||||||

ENHANCEMENT OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGES |

$69,869,987 |

$71,556,614 |

$85,864,659 |

$109,183,551 |

||||||

Data from Public Accounts |

$90,952,187 |

$110,341,443 |

||||||||

Promotion of Inter-cultural Understanding Program |

||||||||||

Subventions |

$468,984 |

$353,467 |

||||||||

Contributions |

$90,483,203 |

$106,467,119 |

||||||||

Participation in Community and Civic Life Program |

||||||||||

Contributions |

$ - |

$3,520,857 |

||||||||

PROMOTION OF LINGUISTIC DUALITY COMPONENT |

$4,998,029 |

$5,311,528 |

$4,544,399 |

$4,629,739 |

||||||

Support for Linguistic Duality (Appreciation and Rapprochement) |

$3,977,161 |

$4,689,927 |

$4,026,005 |

$4,105,682 |

||||||

(Collaboration in Promotion) |

$3,579,493 |

$3,426,505 |

$3,291,969 |

|||||||

(Support for Innovation) |

$1,110,434 |

$599,500 |

$813,713 |

|||||||

Cooperation with Voluntary Sector (Bilingual Capacity) |

$1,020,868 |

$621,601 |

$518,394 |

$524,057 |

||||||

(Support for Interpretation and Translation) |

$498,726 |

$468,984 |

$353,467 |

|||||||

(Support for Innovation) |

$122,875 |

$49,410 |

$170,590 |

|||||||

SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING COMPONENT |

$64,871,958 |

$66,245,086 |

$81,320,260 |

$104,553,812 |

|||||

FPT agreements on second-language learning |

$43,796,843 |

$45,818,258 |

$55,861,270 |

$80,418,605 |

|||||

Regular Program |

$43,796,843 |

$45,043,258 |

$44,710,394 |

$55,081,029 |

|||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$775,000 |

$11,150,876 |

$25,337,576 |

||||||

Language Development Program |

$344,866 |

||||||||

Complementary Support for Language Learning |

$16,750,249 |

$17,333,208 |

$22,523,101 |

$21,230,498 |

|||||

Regular Program |

$16,846,458 |

$17,745,901 |

$16,532,498 |

||||||

Action Plan for Official Languages |

$486,750 |

$4,777,200 |

$4,698,000 |

||||||

Summer Language Bursaries |

$11,466,774 |

||||||||

Official Language Monitors (second language) |

$5,283,475 |

||||||||

Collaboration with Non-Governmental Sector |

$411,840 |

$562,160 |

$533,745 |

||||||

Young Canada Works (second language or both languages) |

$3,980,000 |

$2,681,780 |

$2,373,729 |

$2,370,964 |

|||||

PROGRAM ADMINISTRATION (excluded from total) |

$9,774,298 |

$9,994,316 |

$11,154,154 |

n/a |

|||||

Expenditures under the Action Plan for Official Languages |

$13,950,000 |

$64,341,056 |

$105,537,524 |

||||||

1.7. Brief evaluation of the Action Plan for Official Languages The publication in the fall of 2005 of the government’s midterm report entitled Update on the Implementation of the Action Plan for Official Languages did not give a clear picture of the results achieved with the initiatives taken thus far. In many cases, especially with respect to education, it was too soon to evaluate the real benefits of the new investments. In her Annual Report 2005-2006, the previous Commissioner of Official Languages, Dyane Adam, applauded some initiatives but was highly critical of others. Her assessment was quite harsh on the whole, noting that “the implementation of the Action Plan has not been as transparent as it could have been. Data on activities and investments are not sufficiently accurate to allow for detailed accountability. In addition, some departments have delayed providing information without a valid explanation.”[29] Her main observations were as follows: § In the education sector, the Commissioner noted that, at the halfway mark, progress is barely discernible. Substantial funding was not released until the end of 2005. § With respect to community development, the most concrete results were achieved in health care where the development of infrastructures and cooperation and training networks is progressing well in French and in English, in Quebec § In the public service, the availability of services in both official languages has levelled off, which supports the Commissioner’s recommendation that the Official Languages Regulations be reviewed. § With respect to justice in the French language, the investments have provided for training activities, the development of legal and linguistic tools, as well as consultation mechanisms and access to justice awareness. § With respect to early childhood development, progress has been made with the inclusion of clauses regarding child care spaces in official language minority communities in agreements signed with the provinces, but research projects have not yet been launched. § Literacy initiatives for the Francophone community are progressing well, but there has been a significant delay for the Anglophone community. § With respect to immigration, it is too soon to evaluate the results since most of the work done has pertained to planning. § The establishment of the Enabling Fund provides for better coordination of the activities of various departments involved in human resources development and employability initiatives for the economy of local communities. § With the greater funding provided, the Public Service Management Agency will be better able to promote linguistic duality in federal institutions, although there is a widening gap between the language training offered and what public servants need. Various observations by the previous Commissioner suggest a link between what is happening in federal institutions and what the communities themselves are experiencing. The community perspective is the primary focus of the analyses following this section, but the Committee considered it important to place Federal Government initiatives in their demographic, legislative and institutional context. This makes it easier to appreciate the real complexity of the task facing the government and also shows that any progress or decline in community vitality in some ways depends directly on the government’s actions, whether good or bad, or its inaction. [4] Unless indicated otherwise, the source of the data in this section is Statistics Canada: the paper based on 2001 census data and prepared for Canadian Heritage and Statistics Canada by Louise Marmen and Jean-Pierre Corbeil, New Canadian Perspectives. Languages in Canada 2001 Census, 2004; Department of Canadian Heritage reports on official languages; the series of brochures produced by the FCFA (Profil de la communauté acadienne et francophone du Canada, 2004); the study conducted by Jack Jedwab for the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages entitled Going Forward: The Evolution of Quebec’s English-Speaking Community, 2004; as well as the study by the Office québécois de la langue française, entitled Les caractéristiques linguistiques de la population du Québec : profil et tendances 1991-2001, 2005. [5] As an indication of the vitality of official language communities, Statistics Canada compiles data on first language and first official language spoken. Throughout this report, unless otherwise indicated, we will refer to the first official language spoken. For example, we will consider French as the “first official language spoken” of a person living outside Quebec if his first language is Romanian, he knows both official languages, but speaks French at home. If we looked only at this person’s first language, he would be excluded from the statistics on Francophone minority communities. The services that the federal government must offer the minority in a region are based on the “first official language spoken.” This distinction is especially important for the Anglophone community in Quebec which includes a large number of immigrants whose first language in not English but who are regarded as “English-speaking.” It is less important for Francophone communities outside Quebec that include few immigrants, although change could be encouraged in this regard. [6] Jean-Pierre Corbeil, Statistics Canada, Study: Literacy and the Official Language Minorities, The Daily, December 19, 2006, pp. 6-8. [7] Jean-Pierre Corbeil, 30 Years of Education: Canada’s Language Groups, Canadian Social Trends, Winter 2003, p. 14. [8] Jean-Guy Vienneau, Court Challenges Program, Le développement et les communautés minoritaires francophones, 1999. [9] Forgues, Éric, M. Beaudin and N. Béland, L’évolution des disparités de revenu entre les francophones et les anglophones du Nouveau-Brunswick de 1970 à 2000, Canadian Institute for Research on Linguistic Minorities, Moncton, October 2006, p. 24. [10] See Attorney General of Manitoba v. Forest, [1979] 2 S.C.R. 1032. [11] Statistics Canada, Quarterly Demographic Estimates, Table 6, p. 90. [12] For a list of key constitutional legislation since Confederation, see the Schedule to the Constitution Act, 1982 — Modernization of the Constitution. [13] A provision similar to the one applicable to Quebec was passed for Manitoba in section 23 of the Manitoba Act, 1870, and for New Brunswick with the addition in 1993 of sections 17 to 19 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. [14] Mahé v. Alberta, (1990) 1 S.C.R. 342 available online at: [15] R. v. Beaulac, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 768. [16] Official Languages Act, Section 2. [17] Prime Minister gives Minister Dion additional responsibilities in the area of official languages, Press Release, April 25, 2001. [18] The Next Act. New Momentum for Canada’s Linguistic Duality. Action Plan for Official Languages, Appendix 1, Accountability and Coordination Framework, Section 7, p. 68.F [19] Idem, Section 17, p. 70. [20] In February 2006, these responsibilities were transferred to the Department of Canadian Heritage, along with the Official Languages Secretariat, which performed these roles. See the “Order Transferring from Privy Council Office to the Department of Canadian Heritage the Control and Supervision of the Official Languages Secretariat.” [21] Given Royal Assent in June 2002, this act is intended to ensure the constitutionality of legislative provisions issued in English only prior to the Official Languages Act of 1969. [22] After the RCMP issued French-only tickets in the part of the National Capital Region located in Quebec, the Federal Court in a decision in 2001 called for measures to address these shortcomings in the act. [23] In February 2006, the Minister of Canadian Heritage delegated to the Minister responsible for Official Languages, Josée Verner, her responsibilities pursuant to Part VII of the Official Languages Act. [24] Part VII of the Official Languages Act. [25] Data from Public Accounts of Canada. This data may vary slightly from that presented by the Department of Canadian Heritage in its annual reports on official languages. [26] Department of Canadian Heritage, 2005-2006 estimations. [27] Data for 2004-2005. There were no transfer payments in 2005-2006 because no Supplementary Estimates were passed. [28] See the statements by the Honourable Josée Verner, Minister for the Francophonie and Official Languages, Evidence, June 8, 2006, 9:25 a.m. These statements indicate the maintenance of the commitments signed on November 3, 2005, under the Protocol for Agreements on Minority-Language Education and Second Language Instruction, 2005-2006 to 2008-2009, signed by the Government of Canada and the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. [29] OCOL, Annual Report 2005-2006, p. 59. |