HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

RESTORING FINANCIAL GOVERNANCE AND

ACCESSIBILITY IN THE EMPLOYMENT

INSURANCE PROGRAM: PART ONE

Since the middle of the 1990s, the cumulative balance in the Employment Insurance (EI) Account — commonly referred to as the EI reserve — has steadily increased and today is regarded by most as excessive. For many, the EI reserve, albeit notional, represents a serious financial governance problem within the EI program. Many, like the Auditor General of Canada, believe that the government has collected much more than it needs to finance EI expenditures irrespective of the period of time considered and that, in this context, the government has not observed the intent of the Employment Insurance Act.

The government’s unwillingness to limit the size of the cumulative balance in the EI Account and, more importantly, to reduce it, has caused a great deal of consternation among employers and employees who contribute to EI. The growing importance of this issue was also part of a proposed amendment to the recent Speech from the Throne. The Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills Development, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities, which broached this subject on several occasions in the 37th Parliament, also recognizes the continued importance of this matter and on 21 October 2004 the Committee agreed unanimously to adopt the following motion:

Pursuant to Standing Order 108 and the Order of Reference contained in the address in reply to the Speech from the Throne, the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills Development, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities study the issue of the Employment Insurance Funds so that the money accumulated is only used for the Employment Insurance Program in the interest of workers and taxpayers by forming a subcommittee charged to undertake this study and that the Committee report back to the House of Commons by December 17, 2004.

The Committee has had the opportunity to discuss and adopt the first eight recommendations of the Subcommittee’s report which are the main body of this interim report. The Committee has not yet had the opportunity to consider the balance of the Subcommittee’s recommendations which can be found as attached in Appendix A of this report.

EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE GOVERNANCE AND THE ROLE OF THE CANADA EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE COMMISSION

The Canada Employment Insurance Commission (CEIC) is a “departmental” corporation listed under Schedule II of the Financial Administration Act. It is made up of four commissioners. The Chair of the Commission is the Deputy Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development. The Vice-Chair is the Associate Deputy Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development. Obviously, both of these positions represent the interests of the government. A third commissioner represents the interests of employers and a fourth commissioner represents the interests of employees. The latter two commissioners are appointed by the Governor in Council for a period of five years, following consultations with organizations representing premium payers. The commissioners representing employers and employees are supposed to represent their respective constituencies by providing the Department with feedback pertaining to policy development, and program implementation and delivery. Some witnesses advised the Subcommittee that this consultation process is sometimes wanting, as some EI policy reforms have been introduced in the absence of effective consultation. The Committee believes that the commissioners representing employers and employees and their respective constituencies must be kept adequately informed of proposed changes in EI policy and that sufficient time must be given to conduct meaningful consultations in this regard.

… let’s not make political decisions. Let’s not say okay we’re going to give extended parental leave for a year without knowing what the implications are on half the economy. If they have four or five employees and lose three or four people, they’re devastated. (Garth Whyte, Canadian Federation of Independent Business)1

… you have to have consultation. If you’re going to change the purposes of the fund, add in a parental leave, you have to consult on that. (David Stewart-Patterson, Canadian Council of Chief Executives)2

CEIC’s mandate is essentially to assist Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC), the department responsible for administering the benefit provisions under the Employment Insurance Act.3 With the help of HRSDC staff, the CEIC assists the Department by making regulations; monitoring and assessing the Employment Insurance Act each year; appointing members of the boards of referees, the first level of appeal regarding benefit eligibility; and, until 2001, setting the annual premium rate subject to the approval of the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the ministers of Finance, and Human Resources and Skills Development.

Most of the witnesses who appeared before the Subcommittee expressed the desire to create a more independent CEIC or another entity that operated at arm’s length from the government. Committee members agree that CEIC’s independence needs to be bolstered, but most of us are hesitant to promote absolute independence in the context of an arm’s-length organization. In addition to the fact that, we, along with many of our witnesses, would like to see the tripartite configuration of the current Commission continue, complete independence could entail a certain amount of operational inertia given the dichotomy of views that exists among the primary stakeholders of this program. If employer and employee interests are to be equally represented, some mechanism is necessary to break the inevitable deadlock that we suspect would prevail in a bipartite governance structure.

Right now essentially you have a worker and an employer commission that has very little power in regard to its responsibility. Most of the powers have been taken away. We believe the government has to be a central part of the EI fund … But as to how you’d set up that structure to ensure it meets our commitment, the devil will be in the details, but we’re clear that we want to see the government remain as a critical part of it, including both workers and employers. (Hassan Yussef, Canadian Labour Congress)4

Committee members support a continuation of tripartite representation. However, we do not support a continuation of the government’s dominance in the Commission’s current organizational structure. Rather, we believe that as the sole contributors to the EI program, employees and employers must be given a much stronger voice in EI program management and policy decisions.

In the view of most Committee members, the Commission must be transformed from its current status as a departmental corporation (akin to a branch of the Department of Human Resources and Skills Development) to a federal government enterprise that offers far more independence and authority to be a real partner in EI governance, especially in terms of overseeing a real EI fund and the restoration of its rate-setting responsibilities. The new EI Commission must also be given a more meaningful role in influencing EI policy decisions. While the Committee acknowledges the government’s primary policy-making role in this regard, those who finance EI must have a stronger voice in influencing the future direction of this very important program. The new Commission must be given the authority to establish its own budget and hire staff, including a chief actuary.

Recommendation 1

The Committee recommends that, in 2005, legislation be tabled in Parliament that would create a new entity called the Employment Insurance Commission. The proposed Employment Insurance Commission would be given the statutory authority to manage and invest employment insurance revenues in the proposed Employment Insurance Fund Account and to transfer these revenues, as required by law, to the Consolidated Revenue Fund in order to cover the cost of employment insurance. This new Crown corporate entity should be governed by commissioners who broadly and equally represent employees and employers. The government should also be represented in the proposed Employment Insurance Commission. The Chair and Vice-chair of the Commission should rotate between employer and employee representatives after serving a two-year term. Commissioners would be appointed by the Governor in Council following consultations with groups representing employment insurance contributors. The operations of the Commission and the funds under its management must be fully accounted for and reported in accordance with generally accepted public sector accounting standards. The Commission should have the authority to make recommendations to the government.

THE CUMULATIVE BALANCE IN THE EMPLOYMENT INSURANCE ACCOUNT AND SAFEGUARDING CONTRIBUTIONS

Section 71 of the Employment Insurance Act establishes, in the Accounts of Canada, an account called the Employment Insurance Account (EI Account). While the Act indicates that all EI revenues and expenditures are to be transacted through the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF), sections 73 to 78 specifically state that these amounts are to be respectively credited and charged to the EI Account. Therefore, the EI Account is essentially a consolidated accounting entity that tracks EI-related financial transactions.5 And since all EI financial transactions are consolidated in the Accounts of Canada, a year-end surplus (deficit) in the EI Account directly increases (decreases) the government’s budgetary balance by an equivalent amount. In other words, when EI revenues exceed expenditures, the federal government’s fiscal position improves by a corresponding amount. The converse is true when EI expenditures exceed revenues. The year-end balance in the EI Account is also tracked over time and this is represented by the cumulative balance, a notional amount that, according to many, is borrowed from the EI Account in the case of a surplus or owed to the CRF in the case of a deficit. This view is further supported by section 76 of the Act, which authorizes the Minister of Finance to pay interest on the cumulative balance in the EI Account in accordance with such terms and conditions and at such rates as are established by the Minister.6

It is important to note that section 77 of the Employment Insurance Act limits the government in terms of what can be charged to the EI Account and, in this regard, expenditures outside the purview of EI may not be used to reduce the cumulative balance in the EI Account. In other words, this cumulative balance cannot be wiped out by paying money out of the CRF to finance health care, defence or any other non-EI related use. There is absolutely no question that most of those who appeared before us believe that today’s cumulative surplus in the EI Account should be earmarked for EI.

… in my view, Parliament did not intend for the EI account to accumulate a surplus beyond what could reasonably be spent on the EI program. Thus, I have concluded that the government has not observed the intent of the Employment Insurance Act. (Sheila Fraser, Auditor General of Canada)7

The extra premium revenue collected since 1994 has not been paid out, not into a reserve account and not into the unemployment insurance account. They went directly into the government coffers. What makes this all the more painful is that these surpluses were built by massive cuts in protection to Canada’s unemployed, who regard the surplus as money borrowed from EI that must be repaid. (Hassan Yussef, Canadian Labour Congress)8

I just wanted to say we would object vehemently to erasing that notional account, because it takes the obligation away from the government when we do run into an economic downturn and they are going to have to look for ways to pay increased benefits, that they don’t come back to us and raise the rate. If we lose that account, that’s exactly what’s going to happen. (Joyce Reynolds, Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association)9

With respect to the accumulated surplus, for a number of years now, many groups and organizations, including our own, have loudly denounced the use of employment insurance surpluses for purposes other than those of the system. We believe a broad debate on this question is necessary. Even though those billions of dollars have already been spent, this way of doing things was highly debatable. We therefore think it is imperative, to say the least, that consideration be given to the possibility of reallocating those amounts to the employment insurance account, from which they should never have been withdrawn. (Pierre Séguin, Centrale des syndicats du Québec)10

I want to remind the committee of the zeal of the federal government’s counsel in the CSN-FTQ’s case against the federal government. They demonstrated that there was no separate unemployment insurance fund … and the judge agreed with them … It’s not true that the federal government can eliminate this surplus at a single stroke, by means of an act, and say that it no longer exists and we have to start from scratch with a separate fund. We won’t accept that. We’re going to go to the Supreme Court if necessary. (Roger Valois, Confédération des syndicats nationaux)11

As regards the use of the accumulated surplus, there is no doubt in our view that the money must be returned to the people who contributed. The only thing is that, in the event of a public debate in which the question would be whether this money should be strictly handed over to unemployed workers, at the cost of reducing the government's fiscal flexibility for all programs and spending, our priority would clearly be to hand it over to workers on the one hand. (Mario Labbé, Centrale des syndicats du Québec)12

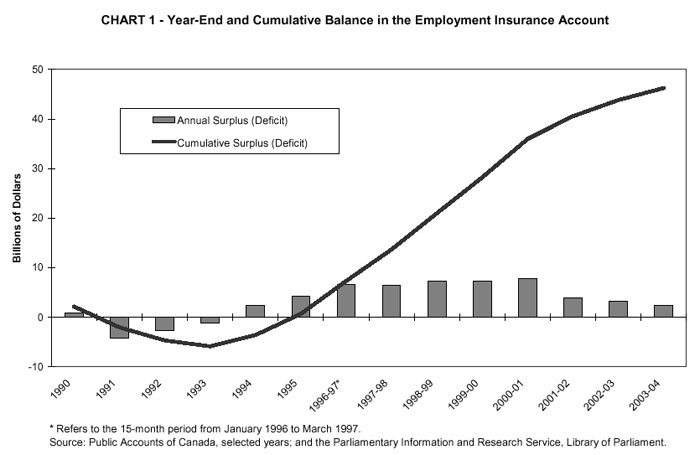

As shown in Chart 1, the cumulative surplus in the EI Account has grown rapidly since 1994 and, according to these data, reached $46 billion as of 31 March 2004. Prior to the implementation of the Employment Insurance Act in 1996, the cumulative balance in the EI Account was always moving toward a break-even level, a function of the premium rate-setting process at that time. This rate-setting process was repealed under the Employment Insurance Act, a subject that is further discussed in the next section of our report.

Not surprisingly, the origin of this unprecedented cumulative balance in the EI Account was a point of discussion throughout our hearings. Many regard the cumulative balance in the EI Account as a product of numerous changes restricting access to EI since the beginning of the 1990s. There is no doubt that the EI reform in 1996 resulted in a smaller program. In fact, one of the reform’s objectives was to reduce EI expenditures by 10%. However, it should be noted that since EI’s inception, subsequent reforms have expanded the program as evidenced by, for example, the reduction in the qualifying period for special benefits, the treatment of small weeks, the extension of parental benefits, the elimination of the intensity rule, a relaxation of the benefit repayment provision, the introduction of compassionate care benefits and, most recently, the introduction of a two-year pilot project extending benefit entitlement by five weeks in high unemployment areas of the country. Changes to EI since 1996 have generally contributed to a slightly more generous and accessible program; but despite increased spending on these measures, the cumulative balance in the EI Account has continued to grow.13

… in terms of changes to the benefits and their impacts, which is more the question you were raising, there’s no question that EI reform going back about 10 years had a number of changes that had the consequence of restricting eligibility requirements. Insofar as more recent years go … each and every change has had the impact of extending eligibility or benefits to deal with particular issues on which we felt that improvements to the program were warranted. So those are a matter of record and they are policy decisions, policy choices, and they do entail costs in addition to what there would have been had there been no change. (Andrew Treusch, Department of Human Resources and Skills Development)14

Departmental officials cited unanticipated strength in the Canadian economy, and its impact on employment growth, as the primary reason for the burgeoning cumulative balance in the EI Account. Although we acknowledge that Canada’s labour market performance may have exceeded private sector forecasters’ expectations, we also recognize that projected EI revenues have consistently and substantially exceeded projected EI expenditures during this period. In other words, like the Auditor General and many of our witnesses, we find it difficult to accept that EI premium rates were being set exclusively within the parameters of the Act.

The vast majority of those who appeared before the Subcommittee maintained that the cumulative balance in the EI Account belonged to the EI program and that the government should begin to use the CRF to reduce the cumulative balance in this Account. A few witnesses seemed to be willing to let bygones be bygones, simply in recognition of the fact that other policy objectives would have to compete with the repatriation of EI funds. Committee members do not support a “let bygones be bygones” view and, like the vast majority of our witnesses, we believe that there is a moral obligation on the part of the government to restore integrity to the Employment Insurance Act. This necessarily requires that the cumulative surplus in the EI Account be returned to the EI program.

I’d like to add one thing that I’m very concerned about. In my view, the cash surplus in the employment insurance fund absolutely must not disappear, absolutely not. It’s money that has been paid by workers … So the money in the fund must absolutely go back to unemployed workers. (France Bibeau, Confédération des syndicats nationaux)15

There is no doubt that for many years the government has been charging employers and employees far more than is necessary to pay the costs of EI benefits … Whether or not you agree with the way that money was spent it has been spent and we can no more undo the excessive EI premiums charged in the past than we can retroactively reverse the lower tax rates that Canadians enjoyed or reverse the transfers that have already been made to provinces for health care over the same period. (David Stewart-Patterson, Canadian Council of Chief Executives)16

Among the overwhelming majority of witnesses who maintained that the cumulative balance in the EI Account should be returned to the EI program, there was a substantial difference of opinion as to how this should be done. Organizations representing employees generally expressed the view that most, if not all, of the cumulative balance in the EI Account should be used to enhance benefits and coverage under the EI program. Organizations representing employers generally favoured a continued reduction in the premium rate as well as changes to other financing-related measures. Committee members also find themselves with differing views regarding how the repatriated surplus should be used.

In our opinion, the first step in resolving this matter is to immediately halt the growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account. We recognize that there are large fiscal implications associated with the repatriation of the EI surplus. We also recognize that premium payers, as well as taxpayers in general, have benefited from spending related to year-end surpluses in the EI Account via spending on other priorities such as health care, increased assistance for higher education, tax relief and debt reduction, to name just a few. However, it is impossible to determine who benefited and by how much.

We believe that the reallocation of CRF funds to the EI program must occur over a sufficiently long period of time so as to recognize the existence of other spending priorities as well as changes in Canada’s fiscal outlook. Finally, and perhaps most important, repatriated surplus EI revenues and EI premiums collected in the future must be managed and used in such a way so that revenues earmarked for EI are spent on EI.

… we really think the time has come again for the segregation of the fund from consolidated general revenues … (Michael Atkinson, Canadian Construction Association)17

Many witnesses who appeared before the Subcommittee were critical of EI’s current governance structure. In their view, and one which is supported by all Committee members, a notional account that is obviously ineffective in guiding the government’s use of funds collected for the purposes of EI is in need of fundamental reform. Most witnesses suggested that the EI Account should be replaced by some kind of trust account or segregated fund, although its operation vis-à-vis public sector accounting principles was often unclear. One suggestion was the creation of an insurance fund like that operated by Ontario’s Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, an entity that is referred to in the notes of the Consolidated Financial Statements of Ontario as a trust fund under administration. We do not think, however, that an entity like this would be satisfactory, because we believe, as indicated earlier, that EI should continue to be controlled by the federal government. In her appearance before the Subcommittee, the Auditor General of Canada clearly expressed the view that if the federal government continued to have control over EI, then EI should be included in the Accounts of Canada. We want to ensure that this is the case as well.

Of course all premiums are currently deposited to the consolidated revenue account, and all payments come from that same account. So there are two factors: revenue and expenditure accounting and the use of cash on hand. Cash on hand is in a bank account and can be used for all kinds of purposes. I assume it’s possible, if Parliament so decides, to establish another, separate account … In accounting terms, it would probably still be in the government’s summary financial statements. (Sheila Fraser, Auditor General of Canada)18

Recommendation 2

The Committee recommends that, in conjunction with the legislation referred to in Recommendation 1, statutory authority be given to establish a new reserve, called the Employment Insurance Fund Account. The Employment Insurance Fund Account, perhaps modelled after the Exchange Fund Account,19 would exist outside of the Consolidated Revenue Fund and act as a depository for all employment insurance premiums and other transfers from the Consolidated Revenue Fund as required by law. Funds transferred from the Employment Insurance Fund Account to the Consolidated Revenue Fund would by law be used exclusively to cover employment insurance costs.

Recommendation 3

The Committee recommends that, beginning in 2005-2006, the federal government transfer amounts from the Consolidated Revenue Fund to the proposed Employment Insurance Fund Account. This transfer must occur over a period of time, taking into consideration the year-to-year fiscal position and expected outlook of the federal government. The minimum amount to be transferred to the Fund each year must be no less than one half of the amount remaining in the Contingency Reserve at year’s end.20 These transfers would continue until the cumulative balance that existed in the Employment Insurance Account as of 31 March 2004 has been fully transferred to the Employment Insurance Fund Account. When the cumulative balance in the Employment Insurance Account reaches zero, all references to this account in the Employment Insurance Act should be repealed.

Between 1972 and 1996, the CEIC (previously known as the Canada Employment and Immigration Commission) was responsible for setting an annual UI (EI) premium rate that served to reduce and eventually eliminate a cumulative surplus or deficit in what was then called the UI Account. Under this rate-setting mechanism, the premium rate was set each year so as to cover what was called the “adjusted basic cost” of UI (EI). This amount was equal to the “average basic cost” of benefit plus (minus) any amount required to remove or reduce a deficit (surplus) in the UI Account. The average basic cost of benefit was equal to a three-year average of UI (EI) costs.21 This approach precluded the build-up of a cumulative balance like that which exists today, unless of course the government intervened and established a statutory rate different from that permitted under the Unemployment Insurance Act.

Although this rate-setting approach served to reduce or eliminate a cumulative surplus or deficit over time, it was susceptible to pro-cyclical rate-setting. In other words, from time to time the premium rate would increase concurrently with the unemployment rate, a point in the business cycle during which lower, not higher, labour costs were needed to stimulate growth in employment. It should be noted that the adverse impact of this rate-setting mechanism was exacerbated, in some years (e.g., 1990, 1991 and 1992) by the withdrawal of taxpayers’ contributions to the program. As of 1990, all CRF payments for UI (EI) benefits ceased and the program became totally financed through employee and employer premiums.

To address the adverse effects of pro-cyclical rate setting, the Employment Insurance Act established a rate-setting process that required the CEIC to set a rate that, to the extent possible, would ensure that enough revenue was available to cover program costs and maintain relatively stable premium rates over the course of the business cycle. Unfortunately, the Act does not define a business cycle or premium rate stability, or set an upper limit on the “reserve,” albeit notional, that would meet these premium rate-setting objectives. Perhaps the greatest shortcoming associated with this rate-setting process is that there is no means of creating a real pool of reserves in order to meet the Act’s rate-setting objectives. While premium rate stability can be achieved in the context of a notional reserve, this approach necessarily has a direct impact on the budgetary balance of the government. By incorporating a cumulative surplus or “look-back” component in the rate-setting process, the CRF must be called into service when the “stable” premium rate is unable to generate enough revenue to cover program costs. There is no doubt that the rate-setting mechanism established under section 66 of the Employment Insurance Act exposed the government to fiscal uncertainty.

I want to remind you, the whole point of the government deciding to move to a new premium-setting mechanism was that since the account was consolidated under this approach that looked back at accumulated surpluses, this could have significant destabilizing impacts on the fiscal management of the government. (Louis Lévesque, Department of Finance)22

In the absence of a legislated limit on growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, EI’s Chief Actuary set about to estimate the magnitude of the notional reserve that would satisfy EI’s rate-setting objectives. According to the Chief Actuary’s Report on Employment Insurance Premium Rates for 1998, an estimated notional reserve of $10 to $15 billion attained just before a downturn would suffice. This estimate was reiterated in subsequent reports covering the period 1999 to 2001. This estimate has not been revised since then, as CEIC’s rate-setting responsibilities were suspended in 2002.

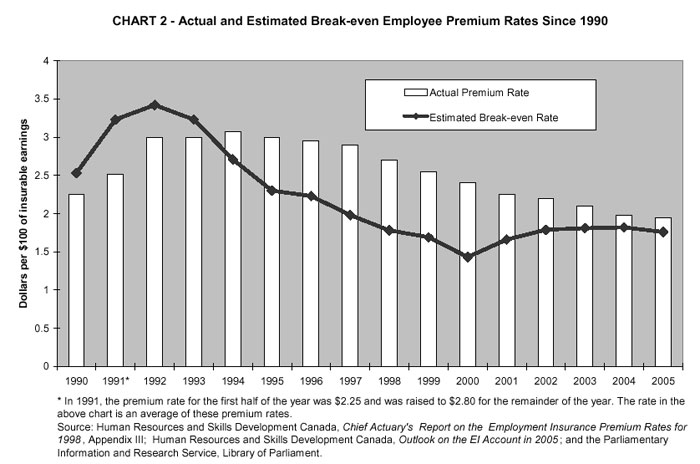

Although this notional reserve (i.e., cumulative balance in the EI Account) was reached around 1997-1998, EI premium rates continued to be set at levels well in excess of those required to cover program costs, as shown in Chart 2. Moreover, between 1998 and 2001, a period during which CEIC remained responsible for setting the premium rate, the government continued to set a premium rate that exceeded the upper end of the Chief Actuary’s estimated long-term stable rate and the recommended rate.23

With mounting pressure to address the continued growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, the government suspended section 66 of the Employment Insurance Act in 2001. In its place, section 66.1 allowed the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the ministers of Human Resources Development (now Human Resources and Skills Development), and Finance to set the EI premium rate for the years 2002 and 2003. The government indicated that during this period it would consult with Canadians and introduce a new premium rate-setting process by the end of 2003.

As this public consultation had not taken place by the time the February 2003 budget was tabled, the government reiterated its intention to consult the public on the creation of a new rate-setting process and extended its rate-setting authority to 2004. The budget also announced that interested parties could submit their views on a new rate-setting process until 30 June 2003. The new rate-setting process would be guided by five principles: (1) premium rates should be set transparently; (2) premium rates should be set on the basis of independent expert advice; (3) expected premium revenues should correspond to expected program costs; (4) premium rate-setting should mitigate the impact on the business cycle; and (5) premium rates should be relatively stable over time.24 Moreover, it was assumed that this new rate-setting process would be in place for 2005. However, in the event that the new process was not in place, the government extended by one year its rate-setting authority in the March 2004 budget. In doing so, it would set the premium rate in a manner consistent with the principles underlying the new rate-setting mechanism.

Since superseding CEIC’s rate-setting responsibilities, the government has continued to set an EI premium rate above that necessary to cover EI program costs (see Chart 2).25 While the Committee acknowledges that the government has reduced the EI premium rate every year since implementing the Employment Insurance Act, the speed at which these rates declined, especially after 1998, pales in comparison to the rate of growth in the cumulative balance in the EI Account; the average break-even EI premium rate (including interest payments) for the period 1998 to 2004 was around $1.70 per $100 of insurable earnings, some $0.61 per $100 of insurable earnings below the average actual rate for the same period.

The Committee recognizes that some of the gap between actual and estimated break-even premium rates is attributable to the fact that the latter includes interest payments. The government does not include interest payments in setting the premium rate, a somewhat odd approach in view of the fact that it pays interest, albeit notionally, on the cumulative balance in the EI Account. Of perhaps greater importance, the government has certainly levied real, not notional, interest charges in the past whenever the Account was running a deficit.

… from a fiscal management standpoint the interest credit is a notional transaction in the sense that it’s the accounting within the EI account, but it has no impact on the fiscal position of the government. What has an impact on the fiscal position of the government is the premium revenues coming in from employers and employees, the benefits in terms of going out, and the administration cost. It’s clear the intent in terms of the new premium-setting mechanism is to take those elements into account, because these are the elements that have a direct impact in any given year on the fiscal position of the government. (Louis Lévesque, Department of Finance)26

I. Looking Ahead: A New Approach to Setting EI Premium Rates

Most witnesses supported the idea of establishing a premium rate on the basis of expected program costs over a specific period of time, say between five and seven years. Others mentioned the business cycle as the rate-setting reference period. Irrespective of the reference period, all seemed to be in agreement that whatever period is selected, it must have a legislative basis.

There was also general support for a look-forward rate-setting process, and, in most cases, the proposed rate-setting model incorporated the concept of a rate stabilization reserve to offset the shortfall in revenues whenever the established rate failed to generate enough funding to cover program costs. Unfortunately, this rate-setting feature was not included in the five principles governing consultations on a new rate-setting process, although it should be noted that most participants addressed this issue anyway.

i. Establishing a Real Premium Rate Stabilization Reserve

As recommended earlier in our report, we believe that the government should enact the necessary legislation to create an Employment Insurance Fund Account. We also propose that the newly created Employment Insurance Commission establish and manage a premium rate stabilization reserve within this Fund, and that this reserve be estimated every five years to ensure that its size is sufficient to cover the cost of estimated program liabilities during the period over which premium rate stability is sought. Moreover, this stabilization reserve should be recalibrated following a major change to the EI program, especially when the change directly affects the program’s cyclical sensitivity.

Some witnesses suggested that a premium rate stabilization reserve should be set at $10 to $15 billion, the estimated, albeit dated, notional reserve that EI’s Chief Actuary deemed sufficient to meet program costs and maintain relatively stable premiums over the business cycle. Most Committee members believe that the Chief Actuary should re-estimate the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve that is necessary to satisfy the aforementioned rate-setting objectives over the rate-setting reference period.

Recommendation 4

The Committee recommends that a premium rate stabilization reserve be created and maintained within the proposed Employment Insurance Fund Account. This reserve should be estimated by the Chief Actuary of the proposed Employment Insurance Commission and re-estimated every five years. It should be managed prudently, provide the required liquidity needed to maintain premium rate stability over a five-year period, and should never exceed 10% of the most recent estimated premium rate stabilization reserve requirement.

Many witnesses either explicitly or implicitly indicated that EI’s Chief Actuary should play an important role in the new rate-setting process. This role would entail estimating the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve, as well as the premium rate that, given this reserve, would meet program costs and maintain stable premiums over the estimation period.

We’ve heard talk of eliminating the actuarial position. That would be outrageous. You need that. If you do not have that, some sort of arm’s-length person, you’ll run into a Workers Compensation Board scenario, where they don’t even do their cost claims studies, some of them, appropriately, and then you get all sorts of mischief happening. (Garth Whyte, Canadian Federation of Independent Business)27

General support also appears to exist for the principle that the premium rate be set on the basis of independent expert advice. We believe that the Chief Actuary should identify and use the necessary independent expert advice in fulfilling the proposed Employment Insurance Commission’s rate-setting mandate.

Committee members, and our witnesses, also support a transparent rate-setting process. In this context, the Chief Actuary would publish, not later than three months prior to the coming year for which the premium rate is to be set, a report outlining the details of the analysis underlying the recommended rate. We recognize that this rate must be approved by the Governor in Council, but Committee members are reluctant to afford the government a great deal of flexibility in revising the Chief Actuary’s and, by association, the proposed Commission’s recommended rate.

Many of those who appeared before the Subcommittee want future premium rates to increase or decrease in order to achieve objectives beyond those associated with the rate-setting process itself. For example, most of the witnesses representing employees recommended that the current premium rate be maintained or even increased so as to help finance, in conjunction with a reduction in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, numerous program enhancements. Groups representing employers, on the other hand, sought a continued reduction in EI premiums via a reduction in the cumulative balance in the EI Account, a rebalancing of employer/employee cost sharing, and higher premium refunds. It was also proposed that the new rate-setting process incorporate experience rating, a feature that would result in higher premium rates being charged to companies that generate above-average program liabilities compared to companies that tend to have relatively greater employment stability.

We think the premium rate should be increased. If we want to improve the employment insurance system, as we wish, the premium rate absolutely must be approximately $2.20 per $100. (René Roy, Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec)28

Given that employers and employees have already paid in over $47 billion in extra premiums to the government for the sole purpose of achieving rate stability, CFIB recommends that the government continue to lower the rates beyond 2004 and take the responsibility for future unexpected program shortfalls associated with the business cycle. (Garth Whyte, Canadian Federation of Independent Business)29

Most Committee members feel that the premium rate should be set annually so as to ensure that the proposed rate stabilization reserve is solvent, that program liabilities can be met and that premiums can remain relatively fixed over a look-forward period of five years. The costs associated with future program enhancements or other changes pertaining to program financing would necessarily be reflected in both the size of the premium rate stabilization reserve and the break-even premium rate covering the rate-setting reference period.

Recommendation 5

The Committee recommends that starting in 2005:

i) the Chief Actuary of the proposed Employment Insurance Commission utilize independent expert advice to estimate annually a break-even premium rate that would ensure program solvency and premium rate stability over a five-year, look-forward period;

ii) the Chief Actuary utilize independent expert advice to estimate quinquennially the size of premium rate stabilization reserve that would insure program solvency and premium rate stability over a five-year period; and

iii) the proposed Employment Insurance Commission publish its recommended break-even premium rate and underlying analysis by 30 September in the year prior to the year for which the recommended rate applies.

Recommendation 6

The Committee recommends that if the rate recommended by the proposed Employment Insurance Commission is, for some extraordinary reason, different from that which the Governor in Council wishes to approve, then the government must, in setting a different rate, amend the Employment Insurance Act by establishing a statutory premium rate for a period not exceeding one year. This proposed legislative change must be subject to a vote in the House of Commons.

I. Yearly Basic Insurable Earnings Exemption

Under the Employment Insurance Act, individuals who are unlikely to qualify for benefits are entitled to a premium refund if their earnings are less than $2,000 per year. Employers are not entitled to these refunds, a situation which understandably was regarded as inequitable by business groups, particularly those representing small businesses, who appeared before the Subcommittee.

In addition to the inequitable treatment afforded employers, the premium refund also has some shortcomings with respect to its treatment of employees. While the purpose of this provision is to refund premiums to workers who are unlikely to qualify for benefits because their earnings are insufficient, it undoubtedly fails to perform this task because it is set too low and it is not indexed to growth in earnings. The current threshold of $2,000 is not high enough to ensure that those with low annual earnings and no chance of meeting EI’s minimum qualification requirement receive a premium refund. For example, combining the lowest minimum wage rate ($5.90 per hour) and the lowest minimum qualification requirement (420 hours of insurable employment), those with annual earnings between $2,000 and $2,478 would not qualify for EI or a premium refund. More importantly, the gap between the current premium refund threshold and other minimum wage and minimum qualification requirement combinations rises as the minimum wage rises and/or the unemployment rate falls in EI economic regions.

In view of the fact that the government seems unwilling to augment the premium refund and devise some means for applying it to employers, the issue of introducing a basic insurable earnings exemption, akin to that used under the Canada Pension Plan, surfaced during the Subcommittee’s hearings. This issue has been raised on other occasions as well and, in fact, was addressed in a report prepared by this committee in May 2001 entitled Beyond Bill C-2: A Review of Other Proposals to Reform Employment Insurance.

… a yearly basic exemption in the EI program would help alleviate the payroll tax burden of all Canadians and all businesses but would most benefit those most punished by high payroll taxes, low wage and entry level workers, and labour intensive businesses. (Joyce Reynolds, Canadian Restaurant and Foodservices Association)30

The Committee agrees that the current limited and one-sided application of the premium refund needs to be addressed, and the introduction of a yearly basic insurable earnings exemption is appealing in at least two respects. Firstly, it alleviates some of the regressivity of EI premiums. Secondly, its application is administratively simple.

However, a yearly basic insurable earnings exemption is wanting in other respects. For one, proponents of this feature assume that exempt earnings would be insurable for the purposes of qualifying, but not for the purposes of premium collection, which seems to be tantamount to free benefit coverage. In addition, if earnings up to the yearly basic insurable earnings exemption are only insurable if earnings exceed the exemption (basically the same treatment afforded pensionable earnings for the purposes of the Canada Pension Plan), then some individuals, for example, multiple job holders might find this approach to be inequitable. In this case, a multiple job holder whose earnings in each of the multiple jobs are less than the earnings exemption could end up with no insurable earnings even though total earnings are well in excess of the insurable earnings exemption. Another issue, although no more serious than that under the Canada Pension Plan, is that a yearly basic insurable earnings exemption might induce some employers to create short-hour jobs that terminate just before the earnings exemption threshold is reached.

Assuming most of the administrative irregularities associated with a yearly basic insurable earnings exemption are adequately addressed and resolved in favour of workers, the Committee is generally supportive of this proposal.

Recommendation 7

The Committee recommends that the government implement a $3,000 yearly basic insurable earnings exemption to replace the premium refund for contributors with low earnings. This exemption threshold would be indexed upward according to growth in average weekly earnings in Canada. This new provision should be reviewed two years after its implementation to examine its impact on hours of work.

II. Return of Over-contributions to Employers

Along the same lines as the premium refund discussed above, employees are entitled to a return of contributions if they contribute more than the maximum amount in any given year, but employers are not afforded the same treatment. The maximum payment by an employee is calculated as the product of the premium rate and maximum insurable earnings divided by 100 (the maximum payment in 2004 is $772.20). All EI premiums paid in excess of the maximum contribution are returned to the contributor. Employers, who pay 1.4 time the employee premium rate, are entitled to a refund of over-contributions only where the actual amount remitted in a given year exceeds the amount they are required to remit on the basis of earnings paid to each employee. Hence, even though an employee has contributed, for example, the maximum amount in previous employment with a different employer in a given year, the employee’s current employer must contribute on the basis of current, not previous, earnings paid to the employee in that year. In other words, employers contribute to EI on behalf of a given employee as if they are the first employer to pay premiums on behalf of that employee.

This anomalous and inequitable treatment arises under the rubric of employee privacy, which, of course, we do not take lightly. Nevertheless, Committee members are somewhat puzzled by the fact that the government has been unable to identify some administrative solution to resolve, at least in part, this problem, given its capacity to create a program as administratively complex as EI.

We’d like to see a mechanism for refunding employers for EI over contributions particularly with respect to associated companies who are treated as a single taxpayer for the purposes of other income tax matters and yet for EI are treated as separate employers. (Michael Atkinson, Canadian Construction Association)31

While it is difficult to quantify the exact level of over-contributions by employers, the level is certainly in the several hundred million dollar range. However, there is currently no mechanism in place to refund employers for over-contributions. Given the fact that EI premiums represent a barrier to job creation, the Canadian Chamber believes that the federal government must immediately implement a system that allows for over-contribution by employers to be refunded by the federal government. (Michael Murphy, Canadian Chamber of Commerce)32

We believe that a more satisfactory approach can be found than currently exists to afford employers, who pay 1.4 time what their employees pay, more equitable treatment regarding over-contribution refunds. The solution, perhaps one that incorporates a first-payer principle, may continue to be inequitable for some employers, but others would be treated far more fairly than is currently the case. Over-contribution refunds need not be paid in reference to specific employees; a lump-sum payment is an option worth considering. In cases involving businesses in which only one employee has worked for the business in a given year, perhaps the permission of that employee could be sought prior to refunding an over-contribution. Finally, and perhaps most important, the solution to this problem should not be administratively complex or costly to deliver. These are but a few suggestions that could be considered in resolving this important matter.

Recommendation 8

The Committee recommends that in 2005 the government devise and implement a method for refunding employment insurance premiums to employers corresponding to over-contributions to employment insurance from employees.

| 1 | House of Commons, Subcommittee on Employment Insurance Funds of the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills Development, Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities (hereafter referred to as SEIF), Evidence, 1st Session, 38th Parliament, Meeting No. 3 (16:20), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 2 | Ibid. (16:30). |

| 3 | The Canada Revenue Agency is responsible for all matters pertaining to insurability, including the collection of premiums. |

| 4 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (20:00), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 5 | Prior to 1986, transactions in the Employment Insurance Account (then called the Unemployment Insurance Account) were only partially integrated into the Accounts of Canada. Since then, the Employment Insurance Account has been fully integrated into the Accounts of Canada. |

| 6 | Currently, the rate paid on the cumulative balance in the EI Account is set at 90% of the monthly average of the three-month Treasury bill rate. Interest is calculated monthly, based on the 30-day average of the cumulative balance in the EI Account. Like the cumulative balance in the EI Account, these interest payments are also notional. Although they constitute part of the cumulative balance in the EI Account, they are not recorded as a public debt charge in the Accounts of Canada. Between 1996-1997 and 2003-2004, the government has made a cumulative notional interest payment totalling some $7.1 billion. |

| 7 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (11:20), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 8 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (19:35), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 9 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (16:00), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 10 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (19:25), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 11 | Ibid. (20:35). |

| 12 | Ibid. (19:55). |

| 13 | The Bloc Québécois does not consider the EI program as generous and accessible and consequently does not support this statement. |

| 14 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (11:45), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 15 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (20:30), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 16 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (15:35), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 17 | Ibid. (15:25). |

| 18 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (11:50), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 19 | The operation of the Exchange Fund Account is governed by the provisions of Part II of the Currency Act. This Account, administered by the Bank of Canada, represents financial claims and obligations of the Government of Canada as a result of foreign exchange operations. Investment income from foreign exchange transactions and net gains and losses are recorded in foreign exchange revenues on the Statement of Operations and Accumulated Deficit. |

| 20 | The Bloc Québécois recommends that at least $1.5 billion a year be refunded to the Employment Insurance Fund. It also recommends, if needed to cover one full year of contribution, a guaranteed payment of $15 billion. If this guaranteed payment is not used, it should be refunded at the rate of $1.5 billion after the payment of the initial $31 billion. |

| 21 | More specifically, the average basic cost of benefit was equal to the average total cost of UI (including administration costs) for the three-year period that ended concurrently with the second year preceding the year for which the average was computed. The premium rate that would cover the average basic cost of benefit was the statutory or minimum premium rate that could be established in a given year. |

| 22 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (12:10), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 23 | In 1998, 1999, 2000 and 2001, the Chief Actuary’s recommended rate was $2.40, $2.30, $2.25 and $2.10 respectively per $100 of insurable earnings; while actual rates were $2.70, $2.55, $2.40 and $2.25 respectively. |

| 24 | Department of Finance, The Budget Plan 2003, 18 February 2003, p. 183. |

| 25 | According to the Chief Actuary’s Outlook for the EI Account in 2004, estimated break-even premium rates (including interest payments) for 2002, 2003 and 2004 were $1.79, $1.77 and $1.81 respectively per $100 of insurable earnings; actual rates, on the other hand, were $2.20, $2.10 and $1.98 respectively. |

| 26 | SEIF, Meeting No. 1 (11:40), Thursday, 4 November 2004. |

| 27 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (16:35), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 28 | SEIF, Meeting No. 2 (19:30), Monday, 15 November 2004. |

| 29 | SEIF, Meeting No. 3 (15:45), Wednesday, 17 November 2004. |

| 30 | Ibid. (15:35). |

| 31 | Ibid. (15:25). |

| 32 | Ibid. (15:45). |