BRIEF FROME THE WELLESLEY INSTITUTE

A good home is essential to health and prosperity

Pre-budget submission from the Wellesley Institute

“People’s ability to find, and afford, good quality housing is crucial to their overall health and well-being, and is a telling index of the state of a country’s social infrastructure. Lack of access to affordable and adequate housing is a pressing problem, and precarious housing contributes to poorer health for many, which leads to pervasive but avoidable health inequalities.”[1]

“In the shorter term, infrastructure and housing investments are widely recognized as an effective means to boost economic activity and put people to work.”[2]

“The Government recognizes the importance of a stable and well-functioning housing market to the overall economy and Canada’s financial system.”[3]

Executive summary:

A good home is vital to personal health and is essential to improving the overall health of the entire population. Good housing contributes to a strong and stable economy. It provides a base for individuals and households to fully participate in the economic life of their communities and the country. It generates good jobs and other investments in a sound, sustainable economy. Good homes reduce government health and other spending, and provide other fiscal benefits. The Wellesley Institute is an independent non-profit research and policy institute that focuses on the social and economic factors that shape population health. Housing is an important social determinant of health; and we and others have done considerable research over the years on its health impact. Inadequate housing and homelessness are major factors in poorer health outcomes for many and damaging health disparities. We are pleased to make this submission on federal housing investments as part of the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Finance’s pre-budget consultations. Our main housing concern in the current pre-budget process: Federal housing investments over the past two decades have not kept pace with inflation, population growth or the growing need for healthy, affordable homes across Canada - creating a heavy burden on lower-income Canadians.

Our recommendation: Maintain federal housing investments at 2010 level of $3 billion through the creation of a new national housing fund that would be supported with taxbased revenues, the allocation of housing-generated revenues from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and innovative financing.

Housing, health and prosperity: Making the links

Poor housing and homelessness leads to poor health and premature death[4]. A growing body of evidence sets out the links between good homes and improved individual and population health, though there is still important work to be done in understanding these links[5]. There is widespread recognition that rapid re-housing of people who are homeless or precariously housed is not only good for individuals, but saves money for governments. A 2006 Wellesley Institute study reported that the monthly cost of a hospital bed was $10,900; the monthly cost of a homeless shelter bed was $1,932; and, the monthly cost of a social housing unit was $193[6]. A 2011 cost benefit analysis from the John Howard Society of Toronto found that transitional housing for men leaving jail lowered recidivism rates (making communities safer through less crime) and was less costly to governments than the costs of police and jails[7].

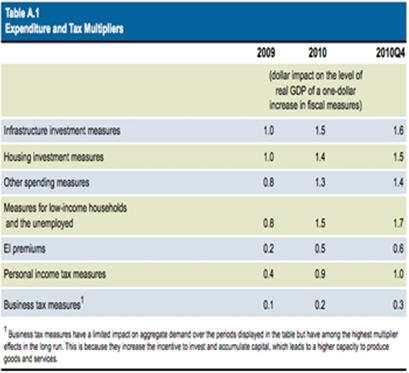

While there are clear health benefits to individuals and communities from good housing, there are also economic benefits from housing investments. The federal government’s latest Economic update (January 2011 - see table one below) reported that the economic activity multiplier (jobs and other economic activity) was among the highest of all federal investments. Federal dollars leverage considerable other dollars. For instance, for every federal dollar invested in a 50-unit seniors affordable housing project built in Ontario recently, five additional dollars were leveraged from provincial, municipal, community and other sources.

Some tenant households have been able to move into ownership in recent decades, many of them assisted under federal affordable housing programs. But in its most recent budget, the federal government has confirmed plans to tighten mortgage eligibility to protect Canada from a US-style mortgage meltdown. This move, designed to bring stability to ownership housing, will put increasing pressure on rental housing, most acutely at the lower end of the rental market. A large number of renter households are vying for a diminishing pool of available, affordable homes.

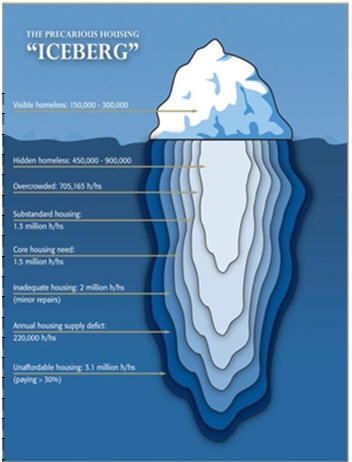

Almost 1.5 million Canadian households (about one-in-eight of all households) lived in core housing need in 2006, according to Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. That same year, more than 3 million Canadian households (about one-in-four of all households) paid 30% or more of their income on housing, according to Statistics Canada. The many dimensions of precarious housing are set out in the iceberg illustration in Precarious Housing in Canada 2010 report (see below). Unlike other countries, including Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand, Canada does not have a robust and timely set of affordable housing indicators[8]. Without reliable indicators, it is impossible to fully assess current housing needs across the country, set appropriate targets and timelines, and monitor the effectiveness of governmental initiatives.

Federal housing investments have been eroding for more than two decades. There are a number of ways to measure declining federal housing investment:

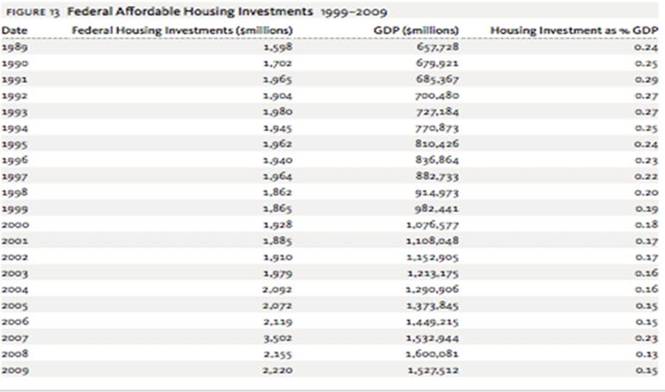

- Falling behind inflation and GDP growth: Federal housing investments of $1.6 billion in 1989 rose by 39% to $2.2 billion in 2009, but inflation grew by 54%. Federal housing spending as a percentage of GDP confirms eroding investments (see table two, below).

- Shrinking federal funds authorized under National Housing Act: In non-budgetary and budgetary envelopes, federal funding from 2005 to 2008 dropped for many programs[9]including: Renovations (down 6%); direct acquisition (down 81%); direct lending (down 1%); affordable housing (down 63%); non-transferred federal housing (down 6%); on-reserve renovation (down 9%). The number of new affordable homes funded annually under s95 of the National Housing Act dropped sharply in 1993. The number of households assisted under federal renovation and related programs dropped by 7% from 2008 to 2009.

- Declining housing investments by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation: CMHC (Canada’s federal housing agency) housing expenses rose from $1.9 billion in 2007 to $3.0 billion in 2010[10] - mainly due to the 2009 housing stimulus. However, CMHC is planning a cut of 43% in its affordable housing program to $1.7 billion in 2015, plus a cut of 14%(85,500 assisted households) from 626,300 households in 2007 to 540,800 by 2015. At the same time, CMHC net income will rise 40% from $1 billion in 2007 to $1.5 billion in 2015.

- Latest spending estimates record cuts to federal housing investments: The federal government’s 2011-12 Spending Estimates set out a 39% cut in housing investments from $3.1 billion last year to $1.9 billion this year, including a 97% cut to the federal affordable housing initiative, a 94% cut to the federal housing repair and renovation and a 70% cut to federal assisted housing - all targeted at low and moderate-income households.

- Short-term federal housing and homelessness initiatives set to expire in 2014: The federal government announced short-term housing investments in 2001, 2006, 2008 and 2009 - all with “scheduled termination” dates of one, two or five years. By 2014, all the short-term funding will expire, including the July 2011 federal-provincial-territorial affordable housing agreement. In addition, the long-term “step out” of federal long-term housing commitments (started in 1996) continues to accelerate - further eroding federal investments.

In the Wellesley Institute’s Precarious Housing in Canada 2010[12] report, we noted that the erosion of federal funding in recent years has put pressure on provincial, territorial and municipal governments. We noted that there is a large, unmet need for additional affordable investments to meet the needs of Canadians who are precariously housed. We recommended a ten-year affordable housing plan funded with contributions from federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments, along with the community and private sectors. As a key part of this ten-year plan, we called on the federal government to sustain its housing investments, instead of allowing them to erode with inflation and the termination of programs. We respectfully submit this housing-related recommendation to the Standing Committee on Finance:

Maintain federal housing investments at 2010 level of $3 billion through the creation of a new national housing fund that would be supported with tax-based revenues, the allocation of housing-generated revenues from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation and innovative financing.

- Create a new national housing fund - incorporating features from the US national housing trust fund and Infrastructure Ontario’s affordable housing loan fund - using government-backed bonds or other innovative financing mechanisms.

- Former US President George W Bush created the US national housing fund, and current President Barack Obama has started to capitalize it. Government-backed affordable housing funds exist at the local, state and national levels in a number of jurisdictions, including several Canadian models in Edmonton, Vancouver and Ottawa. Infrastructure Ontario’s affordable housing loan fund was capitalized through the sale of government bonds. Innovative financing strategies, including tax-exempt bonds, can be used to capitalize a Canadian national housing fund.

- Allocate a portion of the housing-generated income from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation to housing and homelessness investments.

- CMHC net income has been rising steadily from its housing-related commercial operations in recent years, and is forecast to grow rapidly in the coming years. While fiscal prudence dictates that a portion should be set aside to cover possible risks, a significant portion should be allocated for investment in affordable homes. Investing housing-related CMHC revenues in housing-related investments creates a virtuous circle with multiple benefits.

- Support new housing investments with traditional, tax-based revenues.

- We understand the current, constrained fiscal environment and the urgent desire to avoid unnecessary tax raises. This desire should be balanced against other social, health, economic and fiscal priorities. Investing federal dollars today can save federal dollars tomorrow and in subsequent years (and reduce the need for future tax raises). The latest data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development shows that Canada ranks a low 28 out of 34 advanced economies in public social spending (which includes housing). The OECD also reports that Canada’s public social spending is 20% below the average among OECD countries, and the OECD confirms that Canadian public social spending has been falling since 1995. Federal investments in affordable housing leverage significant other investments which, in turn, generate jobs and other economic activity which, in turn, generate tax revenues for government. Affordable housing is a sound economic investment, as the federal government has noted in its Economic Action Plan.

Thank you for the opportunity to make this submission and our recommendation.

Canada’s precarious housing iceberg

Source: Precarious Housing in Canada 2011

Table one: Economic activity multipliers, including housing investment

Source: Government of Canada, Canada’s Economic Action Plan - Seventh Report to Canadians, January 2011

Table two: Federal affordable housing investments relative to GDP

Source: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, Alternative Federal Budget 2011

[1] Wellesley Institute, Precarious Housing in Canada 2010

[2] Government of Canada, Canada’s Economic Action Plan - Seventh Report to Canadians, January 2011.

[3] Government of Canada, Federal Budget, June 6, 2011

[4]For a recent review of the formal and informal literature on the links between poor housing and poor health, see Part One of the Wellesley Institute Precarious Housing in Canada 2010 report. Numerous studies at the local, national and global level all document the relationship between housing and health.

[5] A Wellesley Institute review on the links between good housing and good health is forthcoming

[6] Wellesley Institute, Blueprint to End Homelessness in Toronto, 2006.

[7] John Howard Society of Toronto, Making Toronto Safer, 2011.

[8] An analysis of the UK affordable housing measures has been commissioned by the Wellesley Institute and is expected to be published shortly.

[9] Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Canadian Housing Statistics - Public Funds and National Housing Act (Social Housing), 2009

[10] Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, Summary of Corporate Plan - Financial Highlights, 2007 - 2015. 12 An updated edition will be published in the fall of 2011.