House of Commons, Standing Committee on Finance

Pre-budget Consultation 2011 Submission

Aligning later life, serious-illness,

and end-of-life policy with

sustained economic

recovery and longer-term competitiveness

The Pallium Foundation of Canada

(a community of academic, health services

delivery, voluntary sector, government, and citizen

leaders working to build

sustainable health systems and healthy, secure communities)

in consultation with the

Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA)

August 2011

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Pallium Foundation of Canada is pleased to furnish a brief before the Standing Committee on Finance, detailing two recommendations that will serve Canada and Canadians well in the longerterm, as the government seeks to support job growth, productivity, shared prosperity, and a high standard of living, while balancing the budget.

It this brief a bona fide social investment-based approach is outlined and discussed. This approach has the potential to move Canada beyond the status quo and prepare the foundations for later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life, in which the security of Canadians and Canadian communities are more effectively assured. It is also one that aligns with emerging models of more effectively managing complex, chronic disease, within community contexts.

The essential strategy underlying the approach is called Canadian Compassionate Communities. Canadian Compassionate Communities considers Canadians’ health as an outcome and a national asset, effectively returning to the intended roots of our contemporary systems. It creates the potential to leverage new value for invested dollars. It does this by more broadly sharing accountabilities for support of those in later-life, the seriously-ill, and the dying as a shared local commitment among Canadians where under-developed community capacity may exist; and where Canadians are prepared to engage, nurture, and develop compassionate communities as a legitimate social cohesion commitment of compassion among, and with, fellow citizens.

The brief details the rationale for specific, one-time transitional investments to accommodate an anticipated large-scale, generational renewal of the health workforce this decade, so knowledge is effectively transferred and trust-based relationships among local stakeholders are maintained.

This brief also outlines a way of thinking where compassion and competitiveness can co-exist. It specifically flags business continuity of small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) as associated with unanticipated terminal-illness and dying as an enterprise risk for employees and customers. It also outlines some of the general issues of employee-related retention associated with conflict that is experienced within employees, as they balance roles as skilled workers and their roles and obligations as family caregivers. This is discussed as retention- and productivity-related risk for employers. The need to build new capacity across sectors for shared action is briefly outlined.

The focus of the recommendations is to consider re-orienting the policy foundation in which laterlife, serious-illness and dying issues are engaged, so as to migrate towards improved overall health and security of the population. A call is also urged within the context of the Treasury Board’s, Strategic and Operating Review, that due consideration be given to accommodations for future strategic investments that can be deployed for bona fide social and economic returns.

Recommendation 1 - That the Government of Canada continue to integrate later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life issues as fundamental policy issues of health and security for Canadians and Canadian communities, as it moves forward in establishing a firm foundation for longer-term national prosperity and a balanced budget.

Recommendation 2 - That the Government of Canada make accommodations for future strategic investments in later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life issues, of no less than $100 million over five years, especially for required one-time national transitional investments, as it undertakes the current Treasury Board, Strategic and Operating Review.

INTRODUCTION

From the humanitarian standpoint there is, we believe, an obligation on society to be concerned with the health of its individuals. But on the economic side investments in health are investments in human capital. Just as investments in engines and railroads are investments in capital, so are investments in health. And they pay off in the economic field and they pay great dividends to a nation that looks after the health of its people.

Justice Emmett Hall, Chief Commissioner Royal Commission on Health Services, appearing on National Farm Radio Forum (Nov 2, 1964)[1]

Two years ago, the Pallium Foundation of Canada in partnership with the Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians (CSPCP) and the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA), had the opportunity to submit a written brief[2] as well as present opening remarks and respond to questions before the Standing Committee on Finance[3]. At that time it was stated that:

As Canada emerges from the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression, it is understood the country is at a cross-roads in how leaders think about, and act on, collective abilities and responsibilities for sustaining a rapidly changing society… Enlightened and responsive public policy, including appropriate investments in support of the seriously-ill and dying, is essential for Canada’s elected officials to ‘get right.’ Given the universality of dying, it is also one of the few contemporary public policy issues where there ought to be sufficient shared interest in quality process outcomes to enable the kind of functional, easy-to-understand, and constructive all- party responses so many Canadians desperately seek from their elected leaders.[2]

It is now apparent that in the summer of 2011, the global economy is still in an overall very fragile state. Among G20 nations, there seems to be considerable longer-term risk particularly among the United States of America as well as various European Union nations. Risk also now appears to be manifesting beyond financial and economic foundations to include social cohesion, especially inter- generational cohesion. Canadians are not immune from additional negative impacts to our economy or society[4], but we are well-positioned to move forward from a comparative position of strength. The foundation of that strength will be healthy, secure communities supported with appropriate policy, legislative frameworks, and focused, accountable investments[5] that enable Canadians to balance compassion and competitiveness in the face of unprecedented societal change.

We use this 2011 submission process to briefly situate developments since November 2009, with particular emphasis on addressing three of the four primary issue questions in the 2011 consultation:

- How to achieve a sustained economic recovery in Canada?

- How to create quality, sustainable jobs?

- How to achieve a balanced budget?

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

In the 2009 written submission, the Pallium Foundation of Canada and its partners recommended the Government of Canada act in alignment with the long-standing call of the Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada (QELCCC) to invest $20 million annually[6]in order to assure that Canadians have access to end-of-life care services that are integrated into the health system.

The Pallium Foundation of Canada more specifically recommended a Canadian Palliative and End-of- Life Care Capacity-Building Fund of at least $20 million annually for a period of at least five years. A second recommendation in the 2009 submission was for a re-investment of at least $16 million over five years for a Palliative and End-of-Life Policy Research Innovations Fund. No allocations were made.

Since appearing at FINA in the 40th Parliament on November 5, 2009, the Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada (QELCCC) has released a recommended 10 year Action Plan[7]in January 2010 and CHPCA reappeared before FINA on October 5, 2010[8]. The Pallium Foundation of Canada, as a long- time Associate Member of QELCCC, endorses the QELCCC 10 year Action Plan. Since mid-2010, there has also been an ad-hoc committee of the House of Commons that has been strategically studying four areas of palliative and compassionate care: 1) palliative care, 2) suicide prevention, 3) elder abuse, and 4) disability issues[9]. Committee final reports are expected to be released in late 2011.

Within this context it should be re-stated that investments in quality health services for access to hospice palliative care services for Canadians are a necessary, but insufficient condition to assure the health of Canadians and healthy, secure communities. As briefly reminded by Justice Hall’s 1964 remarks at the outset of the Introduction, it is principally investments in the health of Canadians (outcomes), not expenditures on health services (inputs), that guided the original policy intent of public-funded participation in contemporary delivery systems. That is, it was prudent investment in the health status of Canadians and not an entitlement to services that guided intended policy design.

As the Government of Canada’s single-largest executing partner to-date[10] for translating innovation and collaboration into meaningful supports for the seriously-ill and dying, Pallium has been proceeding with a solution-based response called Canadian Compassionate Communities. Canadian Compassionate Communities extends the QELCCC Action Plan to focus principally on the health of all Canadians as both an outcome and national asset, through strategic community capacity-building.

A Compassionate Communities approach is best understood at the highest-level as a next-generation, public health response to palliative and end-of-life care[11]AND one which is social-investment based. Compassionate Communities’ design is located within the 1986 WHO Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. It seeks to facilitate new capacity within existing systems and community structures based on the five themes of the Ottawa Charter, including: 1) building healthy public policy, 2) creating supportive environments, 3) strengthening community action, 4) developing personal skills, and 5) re-orienting health care services toward prevention of illness and promotion of health.[12]A $3 million one-time investment has been allocated in Budget 2011/12 to complete essential foundation building work on community-integrated models as discussed herein.

A separate Confirmation of Intent for the available funding has been tabled with the Minister of Finance to assure allocation for community-integrated models, in partnership between the Pallium Foundation of Canada, the CHPCA as Secretariat for the QELCCC, and other cross-sector partners as required to strengthen healthy, secure communities. It will secondarily help inform recommendations about future Government of Canada investments, with a sensibility to the work being undertaken by the Treasury Board, Sub-committee on the Strategic and Operating Review. Through a process of foundation building and due diligence anticipated to commence in Fall 2011, a much clearer picture and costing of essential forward-moving investments is anticipated for fiscal 2013/14 and beyond.

SUSTAINED ECONOMIC RECOVERY, QUALITY SUSTAINABLE JOBS, AND A BALANCED BUDGET

The following presents an integrated discussion as it pertains to three of the four issues/questions in the scope of the 2011 FINA pre-budget consultation:

Strategic Investments in health services for later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life - As a practical matter the Government of Canada will be challenged to innovate in its own capacity as one of the largest providers of health services to Canadians[13]. It has also gone on record as funding partner with the provinces and territories in support of health delivery systems[14]. Within the realm of legitimate federal participation[15], re-investment will be challenged to focus on more carefully integrated and seamless palliative and end-of-life care services across primary-, referral- and speciality-areas of service delivery as well as end-of-life integration within chronic disease prevention and management (CDPM) strategies[16], evolving at the provincial and territorial service-delivery levels.

Chronic disease is by definition progressive and ultimately contributes to decline and death, historically with multiple and major co-morbidities the more decades one lives (e.g., heart disease, respiratory illness, renal [kidney] disease, dementia, diabetes, arthritis, pain, etc.). More recent study indicates this may not necessarily have to be so.[17]More responsive models sensible to a proliferation of complex chronic illness will be required and will need to include end-of-life issue integration. As the Government of Canada prepares for negotiations with the provinces and territories in the detailed work of renewing the 2004 Health Accord in ways which are sustainable and accountable to Canadians, it will be challenged about how new expenditures are best leveraged as strategic investments for the health and overall security of Canadians, as part of balancing budgets.

It is also challenged to consider its leadership roles in facilitating meaningful innovation and change, particularly as it informs delivery system sustainability. More Canadians will expect this level of shared political leadership and accountability among various levels of government going forward. Most aptly put, Canadians are generally aware, if not always politically-engaged, and they identify with the adage that while there are many levels of government, there is only one level of taxpayer.

Moreover, there is a legitimate federal leadership role in health human resources (HHR) as it pertains to supporting succession management of an anticipated, large-scale transition in the Canadian health workforce of those with clinical and other specialty skills in palliative and end-of-life care. It has been suggested that modern palliative care practice in Canada finds its conceptual and practical origins within oncology-based programs at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, St. Boniface in Winnipeg, and Victoria Hospice Society in the mid-to-late 1970s. From those traditions and others since, a vibrant national community of deeply-committed people serving their fellow Canadians has evolved.

However, much of the Canadian health workforce who have contributed to the field, including national and local-level leaders, have retired/are retiring within this decade. This at a time when there is increasing demand for essential palliative and end-of-life skills and collaborative clinical service delivery. A one-time, multi-year transitional PEoLC HHR investment is required to address this emergent workforce renewal challenge. It is our intention to have a PEoLC HHR response better understood and planned for, including costing, for the 2013/14 pre-budget consultation process.

A more integrated government-wide policy approach to later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life - Since at least 2000[18], the Government of Canada’s implementation approach to end-of-life has been through palliative and end-of-life care services and principally through health care policy lenses[19]. There have been many positive developments from this approach and the Pallium Project’s many collaborators as well as citizens across Canada have been direct beneficiaries. As has been noted earlier in this submission, however, a health care policy approach solely, will be an insufficient policy foundation from which to assure the prosperity of Canadians on a longer-term basis, especially where health and security are considered an irreducible aspect of prosperity/quality-of-life.

Increasingly, the security of Canadians and Canadian communities will present as the logical policy base from which to further develop later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life policies to strengthen the social and economic fabric of the country, including health, public, and income/economic security, etc. This was the original intent, in part, of the Human Security approach[20]. Human Security has applications for Canadians, notwithstanding the narrow policy lenses adopted by previous Canadian parliaments as the ‘responsibility of protect’ policy variants in international relations[21].

Accountable, ‘upstream’ investments in community capacity and other appropriate responses ought to be guided by how they predictably assure the security of Canadians and Canadian communities. This includes being frank and honest about the prospective longer-term impact that indebtedness of Canadian households may have not only on poverty among the elderly and others, but also on an increased likelihood of physical, emotional[22], financial and other elder abuse[23]within the family unit and community. It also includes being more responsive to loneliness, fear, despair, a sense of abandonment, as well as other bona fide mental-illnesses that more Canadians may experience, resulting in public security threats and criminal acts that cause harm to self and others.[24],[25],[26]

Achieving a balanced budget, in part, suggests making sensible preventative investments earlier to help mitigate and reduce public security and criminal justice costs downstream (e.g., first responder utilization, Emergency Room/trauma unit utilization, provincial/territorial criminal justice administration, property damage mitigation, elder abuse criminal investigation, victim long-term injury, homicide survivorship, citizens’ sense of safety and security in their communities, etc.).

To this end, one pathway to achieving a balanced budget about costly social policy issues, may be to adopt more of a ‘precautionary principle’ approach in the context of predictable security threats as they manifest in later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life contexts. This can be somewhat informed by a determinants of health approach.[27]This would be an innovative approach to Canadian policy and future investments, but may be understandably plagued with some accountability challenges based on present metrics and program accounting models/frameworks (i.e., how is something measured that was mitigated of downstream impact or that never happened because it was prevented?).

Recognizing and acting on the linkage between compassion and competitiveness - FINA is soliciting the thoughts and suggestions of Canadians about attaining high-levels of job growth and business investment in order ensure shared prosperity and a high standard of living. There are at least two aspects applicable to the policy interface between compassion (i.e., later-life, serious-illness, end-of- life policy) and competitiveness (i.e., productive capacity, productivity, skilled labour availability).

Business continuity - There appears to be a considerable, poorly-understood, and poorly-studied enterprise risk, especially among many of Canada’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), associated with serious-illness and dying. Since at least the mid-1980s, much of the restructuring of Canadian sectors has taken place in ways that have shifted the supply chain capacity for larger, public-traded companies to smaller and medium-sized (SME) specialty enterprises, especially in rural western, northern, and Atlantic Canada. That is, large publicly-traded firms especially in the west have come to rely on large networks of smaller service and specialty enterprises since the late 1980s[28]. There are early indications of some contraction in these supply chains in smaller centres. This may become somewhat of a due diligence consideration for at least some future investment flows.

Early indications are that there may be considerable business continuity and hence economic risks to employees (and their families) of SMEs and customers, especially where firms are owner-managed or family-managed, and business continuity/succession plans are not in place for an enterprise to survive an unexpected onset terminal-illness or death of a principal(s)[29]. Conversely, there appears to be at least some consolidation of owner-managed and family-firms by larger public-traded and privately-held equity firms, with local decision-making moving out of the community-level[30].

In the 2010, Securing the Future report[31], the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) noted family business succession planning lag/inaction is often associated with capital gains tax policy issues, which CFIB argues serves as a policy disincentive for more proactive and earlier succession planning. As with advance care planning, the poorest time to address enterprise continuity is during times of personal or family duress, such as terminal-illness or impending death.

At this first-level, there is an opportunity to extend the early work in conversations about planning for care being advanced by the QELCCC, to include earlier intervention within community economic development strategies. So, there is the opportunity to facilitate, through Canada Futures Corporations and the Government of Canada ’s various regional economic development agencies, specific programming to support enterprise continuity for sustainable local employment and growth.

Employee-retention and productivity - at a second-level, the Government of Canada, employer associations, and employers proper, are challenged to be sensible in recognizing the link between the available future workforce and family health and caregiving expectations/obligations. As more of the population ages and more Canadians migrate to major regional economic centres for gainful employment, no one should be surprised to see increases in personal and family conflict as well as substantial individual and aggregated productivity challenges among Canadian workplaces.

That is, role conflict within persons who are offering their skilled, productive labour as economic contributors to the country and their family units, while trying to balance their caregiver roles[32]and obligations[33]within the extended family. There have been anecdotal accounts about these conflicts emerging within the Pallium community, particularly about skilled labour from rural Atlantic Canada locales, with workers who ‘fly in, fly out’ on multi-week rotations from their communities to northern Alberta. In an emerging era of tightening labour supply, governments and employers at all levels will be challenged to be much more sensible about family caregiver issues and supports, including local community capacity that provides flexible networks of safe, shared, community-based caring.

INVESTING FOR PREDICTABLE POPULATION CHANGE

There is a clear link between social policy and economic policy, which in this context has been discussed at two-levels as aligning compassion with competitiveness. This should not be taken as a definitive or authoritative discussion on these matters, but rather as one input for considering future policy and program investments within a social-economic approach that uses bona fide, Social Return on Investment (SROI) models when assessing alternatives for finite public resources. Moreover, it is important to recognize that Canadian disease-based and other organizations have been doing early applied study in this area going back to at least 2006, including the Canadian Strategy on Cancer Control[34], Alzheimer Canada[35], the Canadian Breast Cancer Network[36], and Investor’s Group[37]. There is also an emerging body of Canadian peer-reviewed publications[38].

The issues discussed in this submission are not ‘if’, but ‘when’ and ‘to what degree’ type of considerations. Many of them are of a complex, multi-disciplinary nature. The evidence-base for many has yet to be fully-developed, but the experience-base and status of issues discussed herein as ‘canaries in the coalmine’ warrant federal-level deliberation. Mortality projections for social security programs in Canada as prepared by Canada’s chief actuary indicate these issues will impact on a longer-term basis as it applies to balanced budgets and a sustained economic recovery.

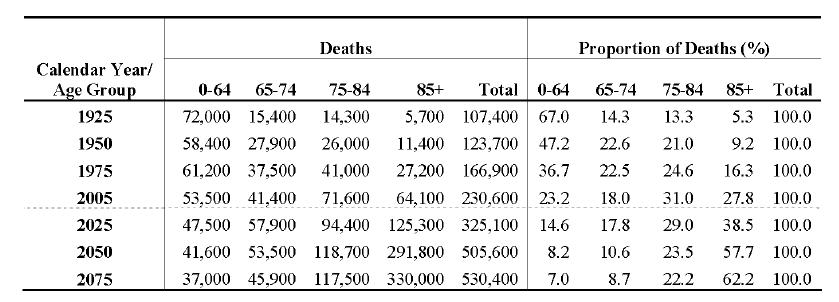

Table 1[39]

Mortality Projections for Social Security Programs in Canada

RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendation 1 - That the Government of Canada continue to integrate later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life issues as fundamental policy issues of health and security for Canadians and Canadian communities, as it moves forward in establishing a firm foundation for longer-term national prosperity and a balanced budget.

Recommendation 2 - That the Government of Canada make accommodations for future strategic investments in later-life, serious-illness, and end-of-life issues, of no less than $100 million over five years, especially for required one-time national transitional investments, as it undertakes the current Treasury Board, Strategic and Operating Review.

CONCLUDING STATEMENT

It is worth re-stating here, as it was similarly stated in the 2009 written submission, that issues about later-life, serious-illness, and dying are understandably complex, but the conclusion about public investment is simple. Canada can invest in priority infrastructures now, or it will predictably pay much higher financial and human-suffering costs soon. The longer issue engagement and strategic public investment is delayed, the greater the risk to sustainability of essential social and economic infrastructures. Canada has enjoyed widely-held, international respect for its early leadership and advances in palliative and end-of-life clinical research, policy and programmatic innovations. Canadians have only started to explore the outer boundaries of what well-designed, developed and executed solutions can do. Sensible, focused investments in enhanced Canadian capacity is essential to sustaining Canadian productivity, economic competitiveness and quality-of-living.

Contact Information

José L Pereira, MBChB, DA, CCFP, MSc

Director, Pallium Foundation of Canada c/o

Bruyère Continuing Care, Palliative

Care Office

Phone 613 562-6262, Ext 4008

Email dricottilli@bruyere.org

43 Bruyère Street, Ottawa, ON

K1N-5C8

Prepared August 2011 by Michael Aherne, CMC, with the input and approval of the Pallium Foundation of Canada founding Board of Directors and in consultation with the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHCPA). Any errors or omissions remain the sole responsibility of Mr. Aherne and are subject to errata notice at www.pallium.ca/accountability.html

NOTES AND CITATIONS

[1] Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (02 November, 1964). A national health plan (National Farm Radio Forum, Season 25 premiere episode). Access archival episode No. 11 at http://archives.cbc.ca/programs/508/

[2] Pallium Foundation of Canada & CSPCP (2009). Planning for investments in support of the seriously-ill and dying as a public policy response to sustaining Canadian productivity, economic competitiveness and quality-of-living. Submission to the Standing Committee on Finance, 2009 Pre-budget Consultation. Access at http://www.pallium.ca/infoware/FederalPreBudgetConsult_Archival_Nov2009.pdf

[3]Parliament of Canada (05 November, 2009). Evidence from the 2009 Pre-budget Consultation of the Standing Committee on Finance, 40th Parliament, 2nd Session, No. 063. Access at http://www.pallium.ca/infoware/FinanceCommittee_Evidence-PEoLC_5Nov2009.pdf

[4]Beaujot, R., & Ravanera, Z. (2008). Family change and implications for family solidarity and social cohesion. Canadian Studies in Population, 35(1), 73-101. Access August 2011 at http://www.canpopsoc.org/journal/CSPv35n1p73.pdf

[5]Government of the United Kingdom (2009, May). A guide to Social Return on Investment. London, UK: Cabinet Office, Office of the Third Sector. Access 2009 at http://www.sroi-uk.org/component/option,com_docman/task,doc_download/gid,51/Itemid,38/

[6]The challenge of ‘what would do with $20 million a year if you had it?’ was posed by the Hon. Ujjal Dosanjh, as Minister of Health in the 38th Parliament to Sharon Baxter in her capacity CHPCA Secretary to the Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada (QELCCC) in a Centre Block meeting concurrent with Budget 2005/06 debates in May 2005. The $20 million per annum became the planning basis for a June 2005, high-level Framework for a National Strategy for Palliative and End-of-Life Care. A more formal Pan-Canadian Strategy for Palliative and End-of-Life Care was developed by the QELCCC Executive Committee and presented to the annual meeting of the QELCCC in January 2007. Source: Michael Aherne’s personal communications and QELCCC document archive.

[7]QELCCC (2010, January). Blueprint for Action: 2010 - 2020. Ottawa: Quality End-of-Life Care Coalition of Canada c/o CHPCA. Access August 2011 at http://www.qelccc.ca/uploads/files/information_and_resources/ENG_progress_report_2010.pdf

[8]Parliament of Canada (05 October,

2010). Evidence from the 2010 Pre-budget Consultation of the Standing Committee on

Finance, 40th Parliament, 3rd Session, No. 032. Access August 2011 at

http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/hoc/Committee/403/FINA/Evidence/EV4674547/FINAEV32-E.PDF

[9]Website of the ad hoc Committee of the House of Commons dedicated to promoting awareness of, and fostering substantive research on, and constructive dialogue about, palliative and compassionate care in Canada; also referred to as the Parliamentary Committee on Palliative and Compassionate Care (PCPCC). Access at http://www.pcpcc-cpspsc.ca/index_files/Page300.htm

[10]See Pallium Project Accountability web at www.pallium.ca/accountability.html

[11]Canadian Compassionate Communities largely follows the conceptual base of a public health/health promotion approach to palliative and end-of-life care as detailed by Australian sociologist and current Director, Centre for Death & Society at the University of Bath (UK), Allan Kellehear, in Kellehear, A. (2005). Compassionate cities: Public health and end-of-life care. London: Routledge.

[12]World Health Organization (1986). Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf

[13]Romanow, R. (2002). Building on values: The future of healthcare in Canada (Final Report). Ottawa: The Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Access August 2011 at http://tinyurl.com/3byg9gl

[14]Payton, L. (08 April, 2011). The Conservatives and health-care transfers. CBC Election 2011 web. Access at http://tinyurl.com/3cbxjxx

[15Maioni, A. (2002, November). Roles and responsibilities in health care policy. Discussion paper No. 34. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. Access May 2005 at http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/Collection/CP32-79-34-2002E.pdf

[16]Aherne, M. (2005, December). Where is the active management of decline situated in emerging Chronic Disease Management (CDM) approaches? Unpublished monograph. Edmonton: The Pallium Project. Access August 2011 at http://www.pallium.ca/infoware/WorkNote_Aherne_HPC&CDMForPopHealth_06Dec2005-V2.pdf

[17]Robine, J. M., Saito, Y., & Jagger, C. (2009). The relationship between longevity and healthy life expectancy. Quality in Ageing, 10(2),5-14. Access August 2011 at http://tinyurl.com/4xac8rg

[18]Senate of Canada (2000). Quality end-of-life care: The right of every Canadian (Final Report). Subcommittee to update ‘Of Life and Death.’ Ottawa. Access at http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/SEN/Committee/362/upda/rep/repfinjun00-e.htm

[19]It may be argued that the Employment Insurance (EI) based Compassionate Care Benefit program is an income security approach, however, it co-exists with the current health care policy approach. See, for example: Crooks, V. A., & Williams, A. (2008). An evaluation of Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit from a family caregiver’s perspective at end of life. BMC Palliative Care, 7:14. PubMed citation

[20]See paragraph 14 of the March 8, 2010 Report of the UN Secretary General on Human Security (A/64/701) which details the formal origins within the 1994 UN Human Development Report as ‘Freedom from Fear and Freedom from Want’ at http://daccess-dds- ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N10/263/38/PDF/N1026338.pdf?OpenElement. It is also noted that the Human Security approach remains problematic for many nation-state governments, both in concept and definition, especially about issues of sovereignty and the interface/interplay with human rights and other accountabilities to populations within the borders of sovereign nations.

[21]Kettermann, M. C. (2006). The conceptual debate on human security and its relevance for the development of international law. Human Security Perspectives, 1(3), 39-52. Access November 2010 at http://tinyurl.com/3ecbaz9

[22]Yon, Y. (2011). A Canadian study on the comparison of

mid-and-old age emotional spousal abuse: A gender based analysis. International Journal of Victimology, 9(1), 309-325. Access August 2011 at

http://www.jidv.com/njidv/images/pdf/JIDV25/jidv25-yongjie_yon.pdf

[23]Sev’er, A. (2009). More than wife abuse

that has gone old: A conceptual model for violence against the aged in Canada

and the US. Unpublished

monograph. Scarborough, ON: University of Toronto, Department of Sociology.

Access January 2011 at

https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/17675/1/morethan_wifeabuse.pdf

[24]Bourget, D., Gagné, P., & Whitehurst, L. (2010). Domestic homicide and homicide-suicide: The older offender. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 38, 305-311. Access January 2011 at http://www.jaapl.org/cgi/reprint/38/3/305

[25]Wingrove, J. (03 August, 2011). Seniors home blast deemed deliberate: Despondent resident with health and financial problems thought to have set off blast in his apartment that killed neighbour. Globe & Mail, pp. A4. Access at http://tinyurl.com/3cq8coo

[26]Warnica, R. (08 May, 2009). Dying dad killed family: Autopsy confirms double murder, husband’s suicide. The Edmonton Journal, pp. A1, A2. Access May 6, 2009 early report at http://tinyurl.com/3cddrva

[27]Hay, D. I. (2006). Economic arguments for action on the social determinants of health. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada & the Canadian Policy Research Networks. Access August 2011 at http://www.ciws.ca/CPRN_social_determinants_of_health.pdf

[28]APEGGA. (1995, April). Structural change and professional practice: Phase II report. Edmonton: Association of Professional Engineers, Geologists and Geophysicists of Alberta.

[29]For example, Calgary’s Top Notch Construction assets were liquidated upon the death of the company founder (ref, Ritchie Bros. Edmonton site conducts Canada’s largest equipment auction, mining.com, May 1, 2009). Similarly, see Remembering Don Beddoes: Local business icon had strong community, family values of DBC Contractors Ltd, about the long-time Crossfield, Alberta heavy construction contracting entrepreneur whose regional contracting capacity was lost upon his death, as reported in the Rocky View Weekly, March 17, 2009. The Edmonton-based Rod Factory custom car shop (http://www.therodfactory.com/) closed in 2007, resulting in the loss of all employment, following the motor vehicle accident death of the owner-manager, Greg Filipowski.

[30]For example see, Waldie, P., & Leeder, J. (30 November, 2010). Do corporate buyouts signal the end of the family farm? Globe & Mail, accessible online at http://tinyurl.com/3wzjxra

[31]Dawkins, I. (2010, May). Securing the future: Results of the April 2010 Survey on SMEs’ views on the retirement system in Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Federation of Independent Business. Access January 2011 at http://www.cfib-fcei.ca/cfib-documents/5466.pdf

[32]Lockie, S. J., Bottorff, J. L., Robinson, C. A., & Pesut, B. (2010). Experiences of rural family caregivers who assist with commuting for palliative care. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 42(1), 74-91. PubMed citation

[33]Allan, M. (2008). Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I’m 94? The scary demographic reality of aging baby boomers and their children’s liability under criminal and family law. The Advocate (Vancouver Bar Association), 66(4), 501-513.

[34]CSCC. (2006, July). The Canadian Strategy on Cancer Control: A cancer plan for Canada. Ottawa: Canadian Strategy on Cancer Control [implemented post 2006 as the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer]. Access August 2011 at http://tinyurl.com/3sylnv2

[35]Alzheimer Society of Canada (2010). Rising tide: The impact of dementia on Canadian society. Toronto: Alzheimer Canada. Access at http://www.alzheimer.ca/english/rising_tide/rising_tide_report.htm

[36]CBCN. (2010). Breast cancer: Economic impact and labour force re-entry. Ottawa: Canadian Breast Cancer Network. Access at http://www.cbcn.ca/documents/Labour_Force_Re-Entry_Report_ENG_CBCN_2010.pdf

[37]Nice, D. (19 November, 2010). Women, as main caregivers, take a hit in retirement. Globe & Mail, access online at http://tinyurl.com/384cxp9

[38]CIHR. (2009). Palliative and end-of-life care initiative: Impact assessment. Ottawa: Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Access August 2011 at http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/icr_palliative_care_summary_e.pdf

[39]Montambeault, M., & Ménard, J. C. (2008, January). Mortality projections for social security programs in Canada. Proceedings of the Living to 100 and Beyond Symposium. Orlando, FL. As Canada’s Chief Actuary, Jean-Claude Ménard, has helped illustrate through the data in Table 1, it is quite apparent that Canada is experiencing a profound shift in the longevity of its population. It is becoming a society characterized as one of many citizens living into very old age. In 2004, Statistics Canada reported some 226,584 Canadians died, with estimates that by 2020 there will be a 33% increase in deaths approaching some 330,000 deaths each year. What aggregated statistics can not qualitatively or substantially describe, however, are important changes to how large numbers of Canadians will live and die, including impacts on persons, families and communities, as more persons live longer with a range of complex chronic conditions.